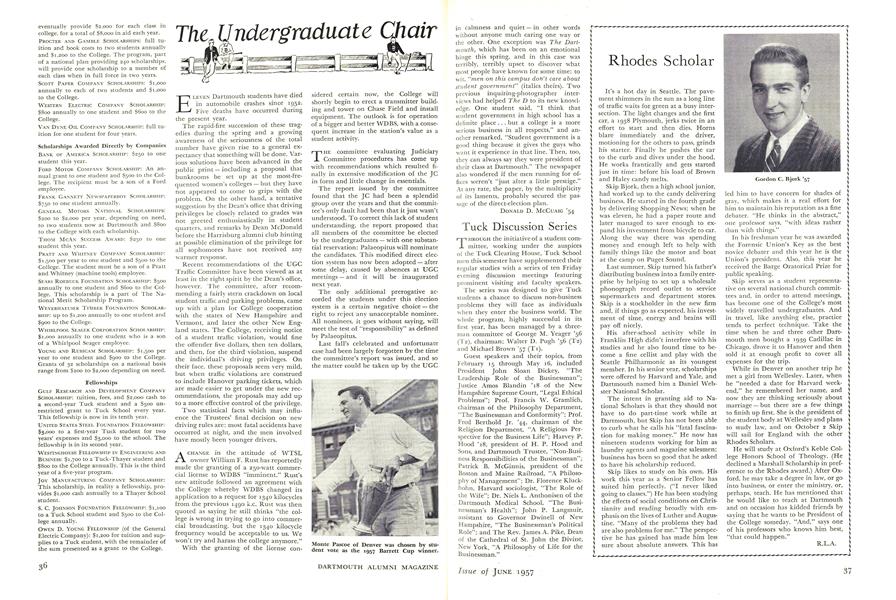

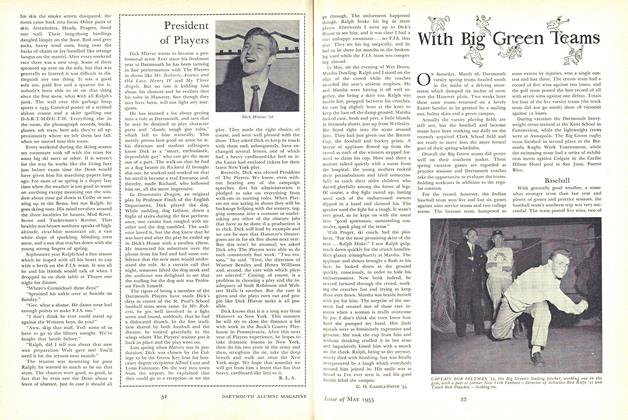

It's a hot day in Seattle. The pavement shimmers in the sun as a long line of traffic waits for green at a busy intersection. The light changes and the first car, a 1938 Plymouth, jerks twice in an effort to start and then dies. Horns blare immediately and the driver, motioning for the others to pass, grinds his starter. Finally he pushes the car to the curb and dives under the hood. He works frantically and gets started just in time: before his load of Brown and Haley candy melts.

Skip Bjork, then a high school junior, had worked up to the candy delivering business. He started in the fourth grade by delivering Shopping News; when he was eleven, he had a paper route and later managed to save enough to expand his investment from bicycle to car. Along the way there was spending money and enough left to help with family things like the motor and boat at the camp on Puget Sound.

Last summer, Skip turned his father's distributing business into a family enterprise by helping to set up a wholesale phonograph record outlet to service supermarkets and department stores. Skip is a stockholder in the new firm and, if things go as expected, his investment of time, energy and brains will pay off nicely.

His after-school activity while in Franklin High didn't interfere with his studies and he also found time to become a fine cellist and play with the Seattle Philharmonic as its youngest member. In his senior year, scholarships were offered by Harvard and Yale, and Dartmouth named him a Daniel Webster National Scholar.

The intent in granting aid to National Scholars is that they should not have to do part-time work while at Dartmouth, but Skip has not been able to curb what he calls his "fatal fascination for making money." He now has nineteen students working for him as laundry agents and magazine salesmen; business has been so good that he asked to have his scholarship reduced.

Skip likes to study on his own. His work this year as a Senior Fellow has suited him perfectly. ("I never liked going to classes.") He has been studying the effects of social conditions on Christianity and reading broadly with emphasis on the lives of Luther and Augustine. "Many of the problems they had are also problems for me." The perspective he has gained has made him less sure about absolute answers. This has led him to have concern for shades of gray, which makes it a real effort for him to maintain his reputation as a fine debater. "He thinks in the abstract," one professor says, "with ideas rather than with things."

In his freshman year he was awarded the Forensic Union's Key as the best novice debater and this year he is the Union's president. Also, this year he received the Barge Oratorical Prize for public speaking.

Skip serves as a student representative on several national church committees and, in order to attend meetings, has become one of the College's most widely travelled undergraduates. And in travel, like anything else, practice tends to perfect technique. Take the time when he and three other Dartmouth men bought a 1939 Cadillac in Chicago, drove it to Hanover and then sold it at enough profit to cover all expenses for the trip.

While in Denver on another trip he met a girl from Wellesley. Later, when he "needed a date for Harvard weekend," he remembered her name, and now they are thinking seriously about marriage - but there are a few things to finish up first. She is the president of the student body at Wellesley and plans to study law, and on October 2 Skip will sail for England with the other Rhodes Scholars.

He will study at Oxford's Keble College Honors School of Theology. (He declined a Marshall Scholarship in preference to the Rhodes award.) After Oxford, he may take a degree in law, or go into business, or enter the ministry, or, perhaps, teach. He has mentioned that he would like to teach at Dartmouth and on occasion has kidded friends by saying that he wants to be President of the College someday. "And," says one of his professors who knows him best, "that could happen."

Gordon C. Bjork '57

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThirty Years After

June 1957 By RICHARD W. HUSBAND '26, -

Feature

FeatureAssignment: Antarctica

June 1957 By DON GUY '38, -

Feature

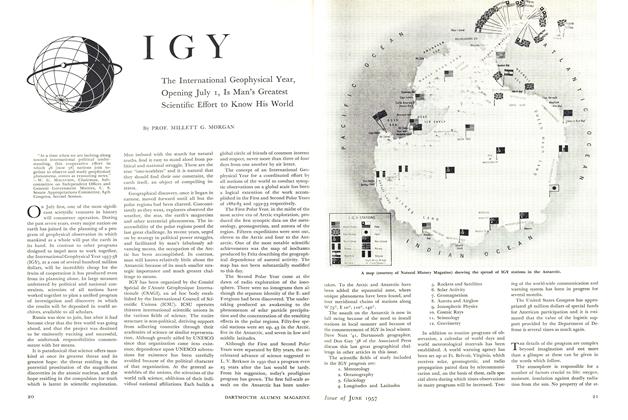

FeatureIGY

June 1957 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN -

Feature

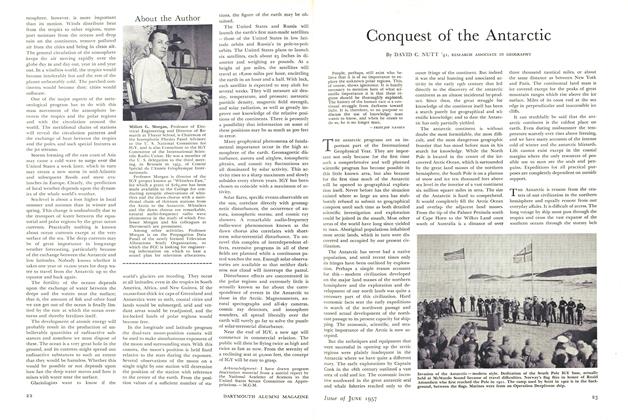

FeatureConquest of the Antarctic

June 1957 By DAVID C. NUTT '41, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

June 1957 By RICHARD W. BOWLEN, FREDERICK K. WATSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1957 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR