ON Thanksgiving Day this month, the Dartmouth Outing Club, in cooperation with the Undergraduate Council, will again play host to some of the orphan boys of New Hampshire at a turkey feast and party at the Ravine Lodge at Mt. Moosilauke. This is the modern-day use that is being made of the famous "Rum and Molasses Fund" given by the late John E. Johnson '66 to provide Thanksgiving solace for Dartmouth boys unable to go home for the holiday.

Back in February 1920, the ALUMNI MAGAZINE printed an article by Mr. Johnson about Dartmouth's Thanksgiving observance, which he called "the oldest old tradition" of the College. The article bears reprinting at this time, the editors feel, and although rum and molasses are not being fed to the orphans, Mr. Johnson would undoubtedly agree that the old tradition is still very much alive and that there is no need for the "thunderbolt of Jersey lightning" that he called down on anyone who would ever let the tradition fail.

Here is Mr. Johnson's captivating story:

THE OLDEST "OLD TRADITION" OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

It is easily identified and is associated with the first observance of Thanksgiving Day in Hanover; Old Father Eleazar had rushed his log college up. It was eighteen feet square and was built like King Solomon's Temple, "without the sound of either saw or hammer." It was said years afterwards of the president of a certain down country institution of learning, that if he had been placed at one end of a log and one student at the other end of it that would have constituted a college. This was a figure of speech which came near being realized in the founding of Dartmouth, the only difference being in the number of logs that it took to do it, a circumstance easily accounted for by the difference in the climate, and the further fact that there was a family in the latter case which had to be provided for. The undergraduate body scorned even the one log and betook themselves to brush booths arranged around a hollow square in the centre of which at night a huge bonfire was maintained, more as a protection from wild animals than from any felt need of either light or heat.

Such was the cradle in which this infant institution was rocked - and yet, breeding true to its pious origin, its workmen first dropped their axes, which were the only tools they had, to celebrate a Day of Thanksgiving. In so doing they not only observed a tradition but established one. They did it in an orthodox manner, that is to say with ancient libations which were the only ones known to them and which consisted of Rum and Molasses, a barrel of one and a keg of the other. The only mistake they appear to have made was in their choice of messengers they sent down to Boston for the conventional materials. Owing to a leakage of the main fluid en route the barrel appeared to be empty when they arrived at Hanover and a new committee had to be sent back for another supply. This necessitated the postponement of the public celebration of the day. It thus became a "movable feast."

What further interruptions of the regular curriculum of the college took place on this occasion we have no means of knowing. Such records as have been preserved are in an unsteady hand and have never been satisfactorily deciphered. In fact it has been maintained by some of the earliest chroniclers that they are in one of the prevalent Indian dialects of that time. So much then for the earliest and one of the most sacred of all of Dartmouth's "traditions." God forbid that it should ever "fail." Every loyal son of the college is in duty bound to maintain it.

But "O tempora, O mores," what a change has come over the manners and the morals of New Hampshire men since those days. Fire-water has given place to milk and water. Sweet cider and maple syrup are now substituted for rum and molasses, and the Dartmouth Outing Club has been forced to serve them in all its camps not even excepting its Thanksgiving Day feasts which are the opening event of their outdoor curriculum.

The means of getting back and forth between Hanover and Boston have been considerably improved since Eleazar's day (except at White River Junction) and the great majority of Dartmouth men now go home for their Thanksgiving orgies, but there is still a considerable number of cowboys, including a few mavericks or motherless calves (by which we mean those who come from over behind Pittsburgh) who find themselves marooned or corralled at Hanover over the Thanksgiving recess. Some of these bear the brand of the Outing Club (D. O. C.). These are "tolled" out, calf-fashion, to the various camps of the club and there fed and watered for a day or two - "Lest the old tradition fail."

So much by way of historical interest and justification. The Outing Club saw in this a trail, - and hit it. Its Carnival builds a bonfire in the middle of the winter and warms the College up. Its Thanksgiving Day "feast of tabernacles" is the "open-door" to the busy business season of the head and heart-culture of the College. It says to the callow freshman who stands shivering and trembling on the threshold of the institution, "Come in, you calf, and get warm and wake up! You are more scared than hurt. The winter which drives you in will bring what you call your mind, out."

This is the time to study. Some of the colleges have their largest attendance in the "dog-days," which in several instances actually exceeds the crowds that rush on sultry afternoons to Ocean Grove, Asbury Park, and even to that down-country Athens of "high living and low-thinking," Coney Island.

Dartmouth's high-water mark is the top of Mount Moosilauke which can best be seen from the college campus in midwinter. Ye great Olympian gods and all ye lesser Parnassan deities and little devils, how is that for a High Altar!

Shade of old Wheelock, of old red Occum, of that Wandering Jew, John Ledyard, and of old Black Dan himself, smite with a thunderbolt of Jersey lightning your degenerate offspring if they ever let this oldest "Old Tradition fail."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

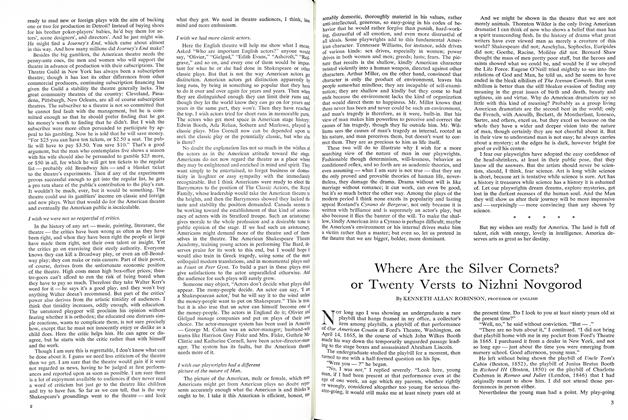

FeatureWhere Are the Silver Cornets? or Twenty Versts to Nizhni Novgorod

November 1958 By KENNETH ALLAN ROBINSON -

Feature

FeatureHow Firm a Foundation?

November 1958 By PROF. HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Feature

FeatureFive Wishes for America

November 1958 By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Feature

FeatureA Community of Learning

November 1958 -

Feature

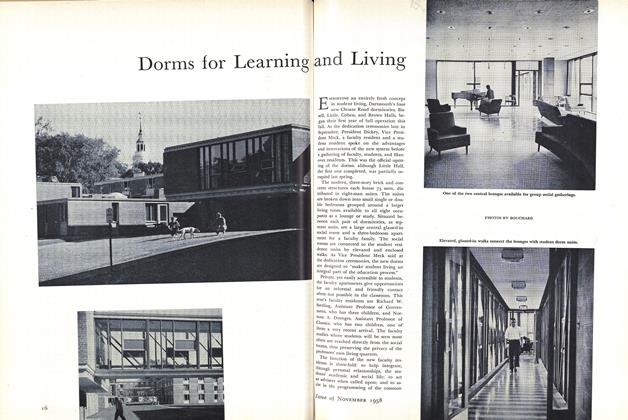

FeatureDorms for Learning and Living

November 1958 By J. B. F. -

Feature

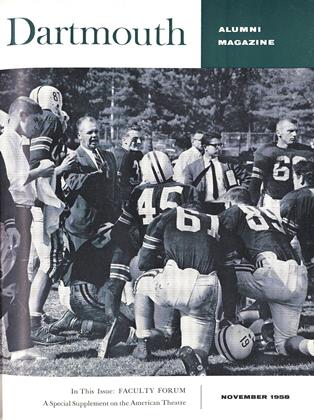

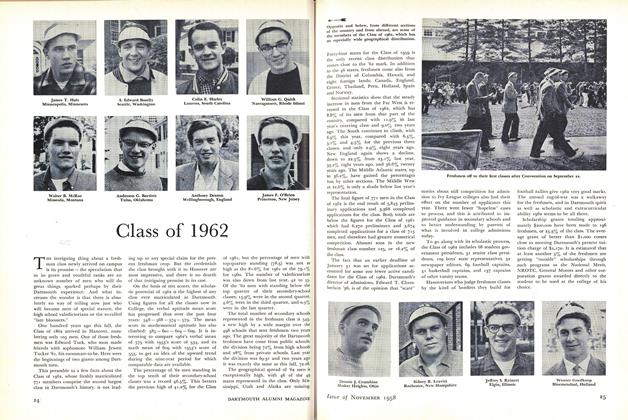

FeatureClass of 1962

November 1958