Now that the college year 1958-59 has started, we have our first opportunity to observe firsthand the new threeterm, three-course system in actual operation. The system has been removed from the planning board and has become a way of academic life for all Dartmouth students. Obviously it is too early for an undergraduate even to think of passing judgment on this new system, but it might be fruitful to explore a few of its more noticeable advantages and disadvantages in the light of their effect on the student.

The advantages are, for the most part, intangible ones, which will take many years to evaluate. However, even in their most hypothetical state, it seems important that the undergraduate keep them in mind. The new curriculum was adopted only after an exhaustive study of its values was made by a planning committee comprised of both faculty members and Trustees. The mere fact that it was accepted and put into effect by a faculty never stampeded where the curriculum is concerned is evidence that much merit was found in it.

The educational advantages to be gained from the mechanical set-up of the new system clearly are evident. Limiting the number of courses from five per semester to three per term, and increasing the number of class meetings from three per course per week to four per week definitely will make the learning period more condensed and meaningful. The "X" hours, or periods set aside each week to be used at the professor's discretion, can also have great additional merit when used for extra seminars or as testing periods.

Another obvious advantage of the new system is the fact that it leaves a great deal of time free in which the conscientious student may use some of the vast educational facilities offered by Dartmouth, either in connection with his course work or for outside academic study. In its ideal sense, this extra time in which the student should utilize both Dartmouth and the surrounding community is meant to develop two main facets of the student in his quest to become academically well-rounded: his maturity and his ability to do independent study.

It is in this realm of independent study that I feel the principal merit of the system lies. Indeed, the assumption that selfeducation is the only real education seems to be the underlying basis of this new curriculum. The habit of independent study, and the intellectual curiosity which must accompany it, will serve the Dartmouth man throughout his entire life. If this one habit can be made an integral part of the student, it may be the most important single thing to be gained from the educational experience at Dartmouth.

The most important and the strongest encouragement given to this concept of independent study is the introduction of the Independent Reading Program. In the junior and senior years this comprises a list of readings given to each student by the department of his major subject, readings to be done on the student's own initiative, and his own time.

The adoption of this new curriculum is, it seems to me, a step toward an educational method which is designed to acquaint the student with the fundamental reason for education in the first place - that is, the realization of educational maturity. The freedom given to the student increases his responsibility both to himself and to his college. It draws a line where the student must either attain some degree of maturity and some sense of judgment, or he will find himself no longer a part of the institution. It is an attempt to arm the Dartmouth man with something more than just book knowledge, for it tries to instill within him a knowledge of the value and usefulness of both his own time and his own capacities.

There is, however, one primary disadvantage inherent in this new curriculum, and that is the fact that this maturity cannot possibly be taught in the classroom, nor can it be left to chance. It would appear to be necessary to develop some subtle guiding force which could, in essence, wean the new Dartmouth from the crutch of heavy scheduling and home discipline found in most students' educational backgrounds. There must be some way to make the student aware of the advantages to be had from using Dartmouth and the community fully. It will be a very difficult task, certainly, but it must be recognized and acted upon, else the aims of the new program will never be fully realized.

For the student who has not yet developed any sense of proportion or values, the amount of work which must be done independently may prove to be overwhelming. He may find that this free time calls for an overload of extracurricular activities, or for too many movies, or for the countless other ways to waste time. It is essential that the student be properly guided right from the start of his college life. One possible solution would be to encourage a much closer relationship between the new Dartmouth student and his faculty adviser, one which could continue throughout the entire time at Dartmouth rather than just through the freshman year, or, as too often happens, just for the first week or two of college.

Should other unforeseen disadvantages develop within the new system, they are not likely to be too difficult to deal with if they are met with determination, for all the elements for a successful curriculum are present. The College must try in every way possible to make what it offers seem attractive and meaningful to the student. The student, in turn, must learn to take advantage of these offerings. This guiding hand which must be held out to the student, though, must be a subtle one, for one of the most important things about Dartmouth, to me, is the fact that while there is an education offered to every student, it is not force-fed. The student's time outside the classroom is really his proving ground, and it should remain that way..

Speaking as one undergraduate, I feel that the new three-term, three-course curriculum is a definite step in the right direction. In its practiced form, it benefits both the students and the College in a very direct manner. Some of the advantages offered to the student could not be achieved to such a high degree with any other system. Responsibility, maturity and good judgment are becoming prerequisites for the Dartmouth student of the future.

But while the new curriculum is good for both the College and the students, the College must not be satisfied with that alone; it must constantly strive for further improvements. To believe that the curriculum is good, and go no further, admits of too many points of impasse beyond which no greater benefits may be reached. The many educational advantages offered by Dartmouth to its students must be exploited to the fullest, and must be made into realities instead of theories.

David J. Garrett '59, guest occupant of the Undergraduate Chair, comes from Youngstown, Ohio. He is an English major and is the treasurer of Delta Tau Delta fraternity.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhere Are the Silver Cornets? or Twenty Versts to Nizhni Novgorod

November 1958 By KENNETH ALLAN ROBINSON -

Feature

FeatureHow Firm a Foundation?

November 1958 By PROF. HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Feature

FeatureFive Wishes for America

November 1958 By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Feature

FeatureA Community of Learning

November 1958 -

Feature

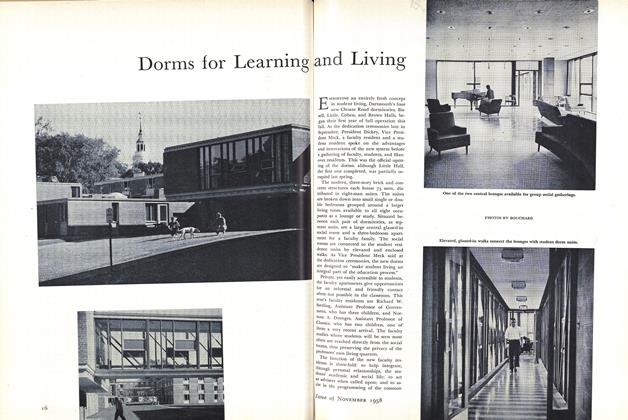

FeatureDorms for Learning and Living

November 1958 By J. B. F. -

Feature

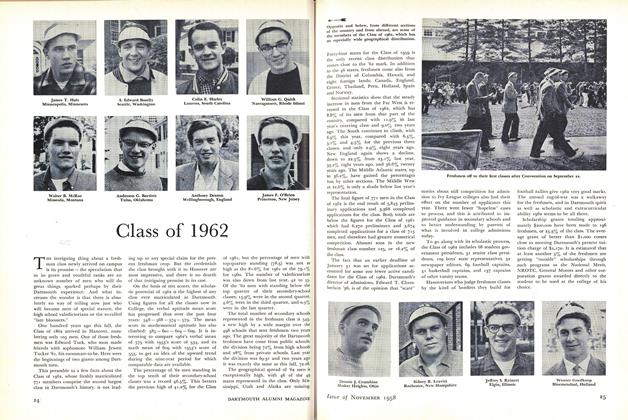

FeatureClass of 1962

November 1958

Article

-

Article

ArticleCAMPUS NOTES

October 1919 -

Article

ArticlePROFESSOR CHARLES H. HITCHCOCK DIES IN HONOLULU

December, 1919 -

Article

ArticleFALL MEETING OF THE TRUSTEES

DECEMBER 1927 -

Article

ArticleAide

January 1943 -

Article

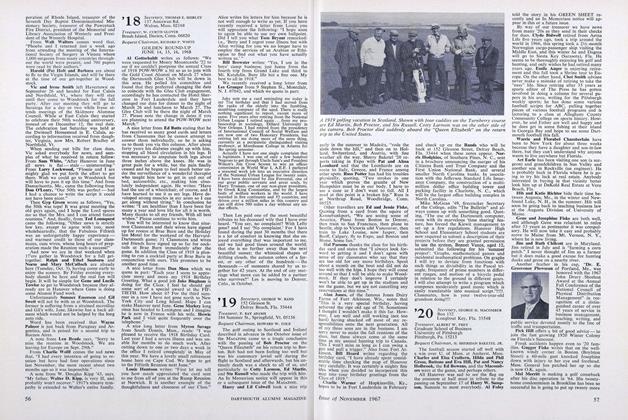

ArticlePeter Kiewit '22 Gets Brotherhood Award

NOVEMBER 1967 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH UNDYING

JANUARY 1932 By Franklin McDuffee