A TRI-MONTHLY SUPPLEMENT TO THE DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE CONTINUING THE EDUCATIONAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FACULTY AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGE

INSTRUCTOR IN ART

IN considering the question of social responsibility in painting, we can begin by condensing the proposition into as few words as possible: either the essential nature of painting includes the concept of communication, or else it doesn't. By communication I mean that process by which one person shares his particular ideas or subjective states with another. The main alternative to this concept would be the consideration of painting as a particular technique by which the painter expresses himself.

Without getting myself intricated in the maze of verbiage on this subject with which the 20th century has been specially blessed, I should like to propose this: if the painter is merely expressing himself, with no thought of communicating his ideas or subjective states to another, then his decision to have his work exhibited is meaningless except in the economic sense. Conversely, if the painter decides to be exhibited, a communicative function for his work is, it would seem, implicit. Since we are normally aware that only those painters exist whose work has been on display, it looks very much as if every painter who exists is dealing with a process and with a product, one of whose essential characteristics is communicative or, to put it more sharply, ought to be communicative.

Of the meanings possible in painting there are four general kinds: formal, representative, generalized, and iconic. Formal meaning inheres in the arrangement of the materials of the language, and is self-referential, i.e., refers to nothing outside itself. Representative meaning deals with the more or less exact image of something existing externally to the art object. Generalized or symbolic meaning has to do with types or exemplars, e.g. hope, faith, justice, motherhood. And iconic meaning is meaning that is peculiar to a given culture, widespread throughout that culture, whose form is more or less strictly determined by the traditional and exclusive institution it designates. The crucifixion would be a good example of this type of meaning.

Of the four types of meaning, the only one which presents difficulties for us is formal meaning. We have all seen many paintings, no doubt, which embody representative, generalized, and iconic meaning, singly and in various combinations. And although we may not have cared much for what we saw, at least we could say that we understood the experience to some extent. Among our other possible discomforts, we were not, at least, bothered by a sense of meaninglessness. In the case of paintings containing nothing but formal meaning, on the other hand, and by this time we are, of course, talking about non-objective paintings, this claim cannot be made. For all of the meaning of the term "formal meaning," one is never quite sure what the meaning is, or even if there is any meaning at all. Formal meaning is the meaning inherent in the arrangement of the materials of the language: an abstract quantity analogous to syntax in the verbal language. Whether this abstract structure, this framework originally intended as the supporting mechanism of the vocabulary of the language, is in itself meaningful remains, I am afraid, for its advocates to assert.

There is a difference between meaning and sensation. There is a difference between sensation, i.e. feeling, and emotion. Meaning has to do with ideas that are, in some measure, capable of being rendered in terms of another language. For instance, if I say, "Man With a Hoe," it is possible to relate very closely the poem with the painting by Millet on whose idea the poem is based. An emotion, as distinct from a sensation, is a complex subjective state which combines an idea, or a combination of ideas, with a feeling about these ideas. An emotion is not a simple sensation, like hot, sweet, hard, etc.

This is, in some measure, supposed to anticipate the objection that, let us say, the non-objective painter is trying to communicate not meanings, but emotions. Tolstoy got that one all straightened out sixty-odd years ago, with only a few minor difficulties. For example, we are never quite sure what Tolstoy meant when he said that through the medium of art, whatever that is, an emotion that the artist has experienced is communicated to other people. Unless this phenomenon takes place, in fact, there is no art.

Whatever may be the merits or demerits of Tolstoy's idea, one thing seems fairly sound: that if the art object provides the occasion or the medium by which an emotion gets across from the painter to the viewer, there are meanings involved as well as the various possible feelings that may attend upon these meanings. In such a case, we cannot but be in the presence of a type of communication requiring a language of some sort.

From what has been said, we may perhaps re-approach the problem this way: is there any substantial difference in the reaction to a painting by, say, Jackson Pollock as opposed to the response to any other handsome object, such as a piece of polished marble with an intricate figure? Is there not, in both, something of a glorified Rorschach test? Are not both, in a sense, tabulae rasae upon which we may write any meaning, or any feeling, which we choose? And is this not, in fact, apt to be one very good reason why certain consumers prefer such paintings or, as the case may be, pieces of marble? I don't know. I merely ask the question.

Of one thing, however, I am pretty certain, and that is that in such paintings there is no evidence of communicable emotion. Our reactions must necessarily be limited to feelings, simple in kind if complex in presentation, feelings which begin at the retina of the eye and may then ramify to more complex associative responses. And these responses, in the absence of identifiable signs, will be distinct and idiosyncratic in each viewer. Do such characteristics not apply equally to a piece of marble, or, let's say to the finger-paintings of a small child at the age when he begins to turn out delightful nonsense that one wants to keep because it is extraordinarily attractive?

But let us consider another aspect of non-objective painting which seems to have arisen with its founder, Wassily Kandinsky. Supposing such painting is like marble. Supposing that it is, in an adult way, of course, like the finger-painting of a small child. It is even more like music, and should be so, since in the past, music is the only art which has been free of the corrupting influence of the desire to represent material objects and situations. According to Kandinsky, the representational art of the past is soulless. And what he proposed to do was embodied in this idea: through a knowledge of color, and unencumbered with material references, the painter will strike, as it were, sympathetic vibrations in the soul of man. Through the spiritual understanding of color, the artist as pianist, is going to play purposively upon color, the keyboard, activating the spectator's eyes, the hammers, which impinge directly on the spectator's soul, the strings. Whether this Rube Goldbergian device works or not has remained, all these years, a rather moot point. Evidently, some of the people who are attracted to Kandinsky's paintings of the pre-Bauhaus period are convinced that the strings of their souls are vibrating. This is something I would not be qualified to determine, I'm afraid, one way or the other.

At any rate, one of the main attempts to justify what in so many ways seems like meaningless painting, involves the supposed resemblance to music.

In music, the composer determines more or less exactly what sounds are going to be heard by the listener and in what order. The listener sits back and, so to speak, takes it. Thus while it is possible, but unnecessary, for the listener to interpret the music actively, in terms of visual images, his role may be said to be passive. The response to paintings, on the other hand, at least in terms of movement, is necessarily active. The painting as an object is stationary. The painter, even in terms of the mere formal meaning of a line, may imply movement, that is, present a sign which will cue the observer to impute a situation involving movement. But no movement takes place except insofar as the observer chooses to imagine the experience of actual movement in space-time. Unlike the composer, the painter can determine only in the most inexact and suggestive way what the observer will see first or last or all at once, or at what tempo he will see them.

If, then, we restrict painting to formal meaning, at which level it most strongly resembles music, we may sum up by saying that the response to music is passive while the response to painting is active, and that while music depends for its very existence on the exact sensation of movement in time prescribed by the composer, sensations of movement as embodied in the formal structure of a given painting are virtual, contingent, potential, and inexact.

It is easy for people to enjoy music without demanding more from it than formal meaning. But what about painting? What happens when an active sense like sight is presented with a visual situation which is not supposed to be merely decorative, and yet reveals no recognizable signs beyond the fact of its very attractive existence? Since it seems to be implied that some response beyond mere optical titillation is indicated, the object becomes a tabula rasa, a psychological hole-in-the-wall into which the observer can climb and there, separated from all normal restrictions, expand indefinitely.

I suppose the crux of this whole situation is that painting, as a language, is capable of more than this. It is capable of pushing the frontiers of meaning as well as of feeling. But the main movements in contemporary painting in the big cities of the world seem to be devoted to the tabula rasa approach. The rage for novelty, characteristic of the Entertainment Age, may be partially responsible for the impetus which abstract expressionism has received in the past few years.

And this situation has two main repercussions. On the elementary level, we have just now wandered into the idea that this type of painting, in relation to what painting as an art is capable of, is defective. No one questions the right of people to buy such paintings; but no one, I suppose, either, would doubt that paintings which push the frontiers of meaning as well as of feeling are more important, more pregnant of the further development of human culture than are paintings which deal with feelings alone. The second repercussion results from the first. Abstract expressionism is partly supported because it represents the first lead that the United States has taken in world art since the country was founded. For the first time, foreign painters are following 57th Street. But this has become such a golden calf that abstract expressionism is everywhere, being painted by thousands of art students as well as professionals. And because it is a painting of action, there is a certain excitement about belonging to the movement which it implies. The psychological climate for a soberer type of painting is thereby made extremely unsound, and the confusion of values which exists not only in painting but in all phases of society is enhanced. This confusion might be reduced by the admission on the part of the action-painters themselves that their paintings are valuable as handsomely colored objects with no further mystical implications. But the movement has the character of a cult, and the statements made by the principal adherents of this cult, if analyzed, are seen to be not only exclusive of other human beings, but in some cases, even antisocial. It is specifically insisted upon, in the case of Clifford Still, one of the great leaders of abstract expressionism, that "Demands for communication are both presumptuous and irrelevant."

Perhaps we could complete the picture in this way: the highest standards of the profession of painting would normally tend to indicate that painting should do the most that it is capable of. To do this, the involvement of meanings as well as feelings is suggested. Abstract expressionism especially does not do this, and the implication would seem to be that, therefore, this type of painting is not living up to the highest standards of the profession. But public exhibition seems to demand public responsibility, which, in turn, would seem to demand that the painter whose work goes on public display by his own consent live up to these highest standards. Since it appears that abstract expressionists are not living up to the highest standards, and are, nonetheless, being widely exhibited, they cannot very well avoid being considered irresponsible.

But, by the same token, a type of painting unwilling to amputate from the art of painting whole levels of potential meaning, with the cultivated feelings attendant on them, would be not only responsible but productive of new meanings to replace the meaninglessness with which our whole culture seems to be plagued.

Postscript

Since 1956, when I first began giving serious thought to the possibility that non-objective painting might be a defective form of the language, I have been increasingly impressed with the amount of opposition there seems to be, especially among the painters themselves, to any notion of a painting ethic or of a social responsibility of the painter. Among the painters with whom I spoke at the meeting of the College Art Association in January 1959, I was unable to find a single person who would even consider the possibility that "art" and "ethics" might exist in the same context. The painter is responsible to himself, solely; any other possibility represents a subversion of the painter's freedom from external interference.

Our legacy of past meanings, inherited from 30,000 years of painting with a social usefulness, is seldom considered by the contemporary painter, it seems, except as a totally unnecessary encumbrance. It does not occur to us, apparently, that we may be unwilling to accept or, more likely, incapable of accepting the challenge to our artistic maturity represented by this vast treasury of pre-20th Century meanings and values.

Seen from this angle, it would appear that to amputate viable meaning from the painting language is to abdicate from the responsibility for struggling with meaning and value, and this at a time when the human race has the greatest need for both of these fundamental qualities. Corollary to this, I think, is the marked tendency on the part of patrons and painters alike to treat the whole painting process, from inception to hanging, with an exclusive and often snobbish epicureanism. The inherent claim to aristocracy springs from a conviction in the ultimate value of cherishing something which nobody else can understand.

Thus a new priesthood is invented whose demand for faith replaces the more ancient demand for intelligibility, and provides for its adherents an emblem of status which stimulates the eye (and too frequently the tongue) without taxing the intelligence.

Recommended Reading

Greene, B., "The Artist's Reluctance to Communicate" in Art News, April 1956, p. 30 ff.

Kandinsky, W., On the Spiritual in Art, New York: Wittenborn, Schultz, 1912.

Miller, D. C. (ed.), 15 Americans, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1952. See especially the statement by Clifford Still, pp. 21-22.

Ortega y Gasset, Don Jose, The Dehumanization of Art andOther Writings on Art and Culture, Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday (Anchor), 1956.

Strunsky, R., "The Cult of Personality" in The AmericanScholar, Summer 1956, p. 265 ff.

Tillich, P., The Courage to Be, Yale University Press, 1952. Concerning the problem of meaninglessness in contemporary life.

MR. MOREY'S ARTICLE is adapted from a talk, bearing the same title, thathe gave before the Ticknor Club at Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOur Place in the Sky

November 1959 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN, -

Feature

FeatureCan Chinese Civilization Survive Communism?

November 1959 By WING-TSIT CHAN -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Fellowship

November 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

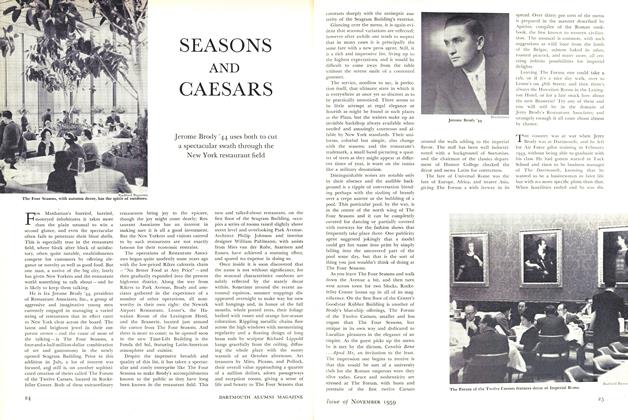

FeatureSEASONS AND CAESARS

November 1959 By JIM FISHER '54 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth and Saint Francis

November 1959 By GORDON M. DAY -

Article

ArticleHow I Conquered Alcohol

November 1959 By ALAN COOKE '55

Features

-

Feature

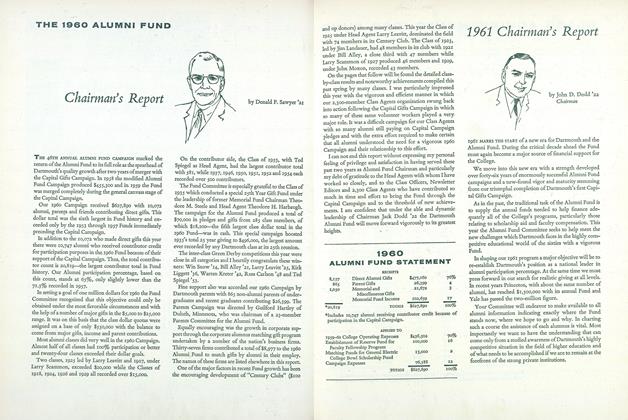

Feature1960 ALUMNI FUND STATEMENT

December 1960 -

Feature

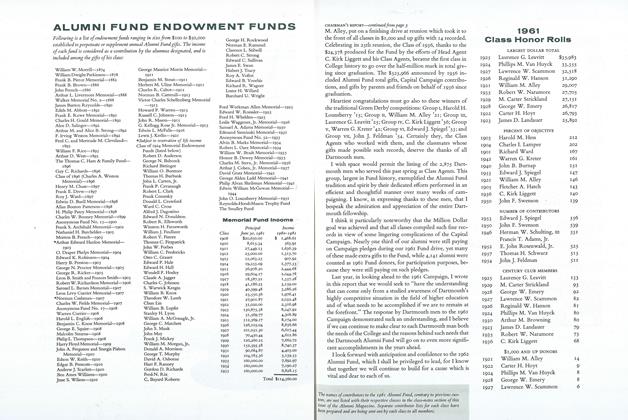

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

November 1961 -

Feature

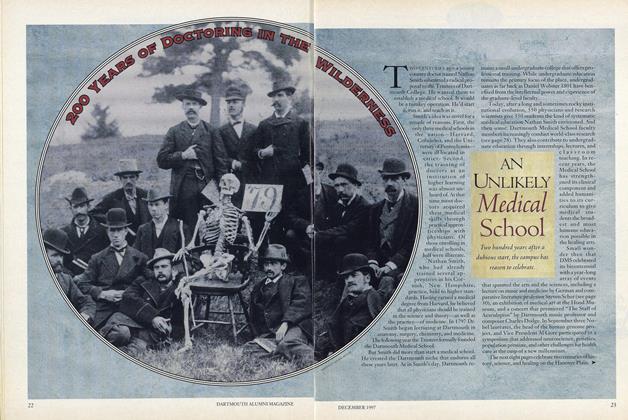

FeatureAn Uulikely Medical School

DECEMBER 1997 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Dissenting Opinion

Nov/Dec 2010 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

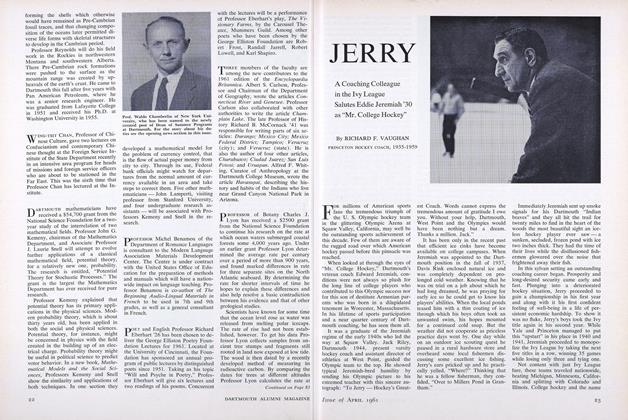

FeatureJERRY

April 1961 By RICHARD F. VAUGHAN -

Feature

FeatureMoriarty Ad Lib

Winter 1993 By Robert Sullivan ’75