Thirtymen interested in analyzing the work of the College as it operated upon them, and as it has continued to affect succeeding generations may wish to recall some comments of a wise Princetonian, Hoyt Hudson. His posthumous little book Educating Liberally (1945) revolves about an apt and simply stated thesis. It is useful as a gauge for measuring in retrospect the Dartmouth tradition and accomplishment as evidenced in our own educational experiences in Hanover.

Hudson noted three enemies which have continually attacked mankind, and which persist in our own time. And these enemies are not, as one might think, Russia, Cancer and the Atomic Bomb. They are more powerful, more widespread, and more difficult to defend ourselves against. The first is ignorance; the second muddleheadedness; the third crossness.

The defense against ignorance is knowledge - and the world forges ahead on that front with more success in some areas than in others, but is gradually pushing back the cloud of ignorance. The defense against muddleheadedness is the establishment of an operative logic. This can be done, and in some areas is being done. Thoughtful planning, administrative know-how, and the application of method, are things with which we as Americans have concerned ourselves, perhaps have taken unjustified pride in.

Crassness, however, is something else again. It is activity based on lack of understanding, lack of sympathetic imagination, lack of appreciation of another's point of view. It has led, and unfortunately continues to lead, every man-jack of us from time to time not only to the brink, but over the brink of stupid blundering deportment. The only defense is the creation of a sympathetic understanding, and of imagination in as many of us as are capable of attaining these qualities. Anything, therefore, that can administer to the imagination and can exercise it may in the end acquire a utility undreamed of by most of us.

But these enemies are apt to come upon us as a combined force, rather than by single instance. They must be met by combined force, and not by any single and overdeveloped antidote. Upon this base the liberal education takes its stand. "Let us not too early, or on too light grounds," wrote Professor Hudson, "divert students or allow them to be diverted into a partial intellectual experience. Limitations enough will be imposed by the circumstances of life outside and after college. Many young people never see college at all, and many will be caught in an illiberal mental life - though not merely because they miss college since the liberal attitude, and the essentials of a liberal education, can be arrived at outside of school or college. But within the circle of education let us not consciously and systematically maim the intellect itself. To do so is to condemn our student out of hand to the fate of being a fractional person, a fate which the liberal education is designed to avert."

How stands Dartmouth amid the defenses against these perennial foes? A question to be asked and a question to be answered as we search our hearts, minds and pocketbooks for the support the College needs. If we believe, as so many of us do, that our liberalizing experience at the College in the late '20s is continuing, well help the faculty and administration gird for the expensive future. The College needs more and larger gifts. Thirty hopes, we hope, that they will flow from appraisal of the way the College continues to fulfill its function, and in anticipation of continued educational leadership among liberal arts colleges.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"The Nasties Upset Since Bunker Hill"

February 1959 By COREY FORD '21h -

Feature

FeatureThat Other Dartmouth Carnival

February 1959 By FREDERICK L. BACON '59 -

Feature

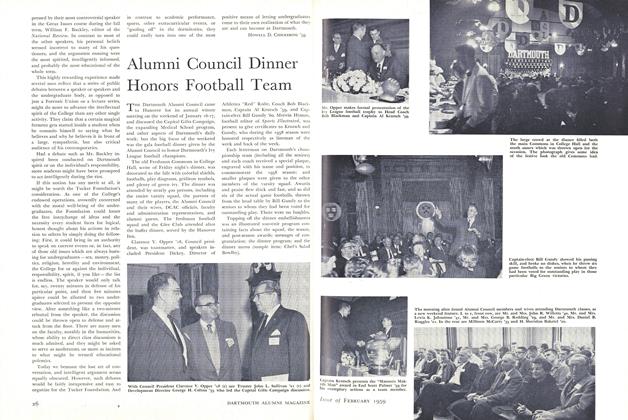

FeatureAlumni Council Dinner Honors Football Team

February 1959 -

Feature

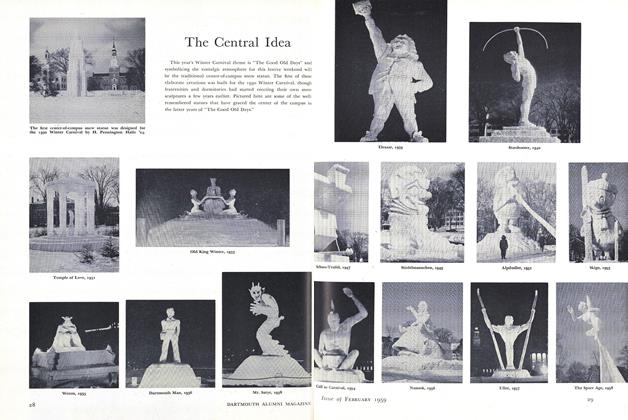

FeatureThe Central Idea

February 1959 -

Article

ArticleSome Consequences of Inflation Psychology

February 1959 By COLIN D. CAMPBELL, -

Article

ArticleShould We Blame the Unions?

February 1959 By MARTIN SEGAL

G. W. STONE JR. '30

Article

-

Article

ArticleSHOTWELL SPEAKS ON WORLD WAR IN HISTORY

April, 1925 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Articles

March 1952 -

Article

ArticleCollege has mixed results on affirmative action

MARCH • 1987 -

Article

ArticleTongue-tied by all the new-fangled terms?

MAY • 1987 -

Article

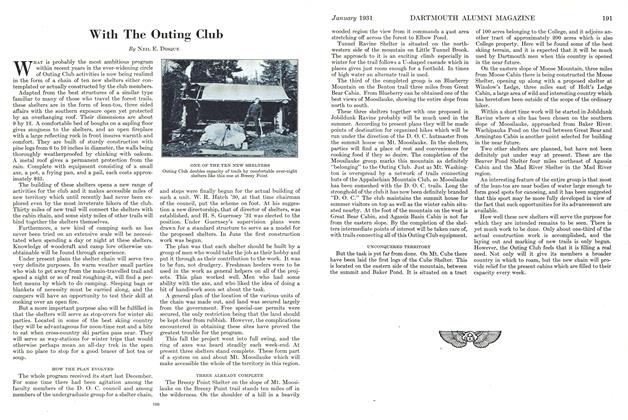

ArticleHOW THE PLAN EVOLVED

January, 1931 By Neil E. Disque -

Article

ArticleJust What Is "Practical"

April 1943 By P. S. M.