ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ECONOMICS

As every beginning student of economics knows, one of the fundamental truisms of our discipline is that everything depends on everything else. And so it is also with the problem at hand. The question whether unions have been responsible for "creeping" inflation cannot be discussed meaningfully without considering some key developments in the economy of post-World War II America.

We begin with what has been the most pervasive, and is likely to be the most enduring, characteristic of the postwar economic environment - the high sensitivity of the American society to the cost of unemployment. The reasons for this sensitivity cannot occupy us here. But it is apparent; that the prevailing public opinion has been that unemployment, even if affecting only six per cent of the work force, is a calamity which must not be tolerated. The community has generally accepted the view that the government is responsible for the maintenance of full employment. What is more, a significant body of public opinion has grown to believe that governmental policies can effectively combat downturns in economic activity.

As a result of this climate of public opinion, the pursuit of fiscal and monetary policies designed to maintain a full-employment level of national income has been embodied into the actual program of any administration - whether Democratic or Republican. For all practical purposes the United States has thus become a country committed to a standard of full-employment economy - or at least to a standard of economy with no more than about four per cent of the labor force unemployed.

This development has left its impact on the course of economic activity in the postwar period. For one thing the fiscal and monetary authorities felt obligated to take immediate steps which would reduce the severity of recessions. To be sure, there was considerable criticism of some of these policies, particularly during the recent downturn. But there seems no doubt that the actions of the authorities contributed to the recovery of the economy. Secondly, the apprehension that restrictive monetary policies may be overdone and may lead to some downturn undoubtedly prevented monetary authorities, in some periods at least, from pursuing more vigorous anti-inflationary policies. Finally, and most importantly perhaps, the very conviction that the government will intervene actively to bring a recovery has fostered a general feeling of optimism and confidence in the long-run prospects of the economy.

Yet, though deliberate fiscal and monetary policies, or expectation of such policies, contributed to the postwar prosperity, the main force of expansion was provided by the private sector of the economy. The initial impetus was imparted by the release of idle cash balances created in wartime. But as it continued, the expansion of the economy was reinforced by other factors - expansion of credit and increased velocity of money, inventory accumulation during the Korean war, rising demand for housing, a boom in the producer-goods industry. True, the cumulative process of spending and respending was interrupted by recessions. Yet these were only short-lived interruptions. And the very shortness of the downturns increased the optimism of businessmen and added force to the subsequent recoveries.

It is not necessary for our purpose to give a full story of the postwar prosperity, or to analyze the role of such additional expansionary factors as government spending for foreign aid and defense, or the farm price support program. What counts here is the fact that the postwar period has witnessed a vast expansion of aggregate demand for goods and services, an expansion which produced considerable strain on the productive capacity of the nation.

During most of the years of this period the nation's resources — labor and capital — were fully utilized. At the same time there was also unsatisfied demand for consumer and capital goods. What is more, this demand was reinforced by expansion of credit and increased velocity of money supply. In these circumstances some degree of inflation was virtually inevitable.

The simplified mechanics of such an inflationary trend can be described very briefly. As business firms and consumers in an already fully employed economy kept bidding for goods, they generated an upward trend in prices. Rising demand and rising prices caused many producers to accumulate inventories, hire new employees and expand output. But as these developments were taking place, workers in general, whether unionized or not, were placed in a highly advantageous bargaining position. To some employers this advantageous position of workers appeared in the form of increased turnover, grumbling in the plant, or actual difficulties in recruiting new labor. But employers in plants covered by collective bargaining saw this advantage in aggressive union demands for steep wage increases.

Expanding demand and high prices made employers highly sensitive to any interruptions in the flow of output, whether in the form of strikes, production "holdbacks" or lower productivity in the plant. In these circumstances, and particularly since cost increases could generally be more than recouped by charging higher prices, employers were willing to grant wage increases which in many cases exceeded productivity gains.

As full employment and a relatively tight labor market continued, these increases spread throughout the economy. Even employers who did not find their markets rapidly expanding or who did not previously raise prices had to follow suit to keep up with the rising wages in their communities. And since the wage increases raised their costs, they too were compelled to make upward price adjustments. Not surprisingly, in view of rising incomes, these employers found that they could generally maintain or even increase their sales at higher prices. Yet, judging from their own experience, they frequently concluded that the basic cause of the inflationary trend was an upward push of wages and a rise in labor costs.

In the absence of restrictive monetary policies, the process described above repeated itself several times during the postwar period. Compensation of employees, i.e. wages and benefits, increased in every year, rising from 1947 to 1957 by about 70 per cent. Because productivity gains offset a large part of this rise, unit labor costs increased in the same period only by about 33 per cent. And prices rose by about the same percentage. In some years the rise in prices preceded labor cost increases; in other years labor cost rises were catching up and exceeding (in percentage terms) price increases.

Thus, over a period of eleven years the result of the creeping inflation was a significant rise in prices and costs. But it is worth emphasizing that for an overwhelming majority of people, a majority which unfortunately did not include college professors, the inflationary period brought also considerable improvement in their real incomes. The reason lies, of course, in the fact that both wages and profits rose much more than prices.

II.

WHAT we sketched above abstracts from many complexities of the actual course of inflation. For one thing, not all industries experienced tight labor markets and steeply rising wages. In the garment and related industries, for example, competition of shops located in rural areas, as well as a high degree of price competition among the producers, kept prices and wages down. Secondly, even excepting the periods of recessions, not all the years of the postwar period witnessed expansion of expenditures which strained the supply of resources in the community. Thus, during the year preceding the last recession we experienced hardly any expansion of real output, and the rising price level was, partly at least, caused by postponed catching up of prices of shelter and services.

Yet even this oversimplified sketch indicates that collective bargaining cannot be singled out as the chief culprit in the inflationary trend. To be sure, union-negotiated wage increases generally exceeded productivity gains and raised labor costs. But this must not be interpreted as being mainly the result of the bargaining power of unions. With a continuous flow of expenditures reflecting demand which could not be satisfied by the productive capacity of the economy, one must expect that costs will rise, whether there are any unions or not. And one must especially expect such cost increases if businessmen and the public believe that both demand for goods and future incomes will continue to rise, and that fiscal and monetary policies will "bail" the economy out of any serious recession. In such circumstances the buying public will not offer much resistance to higher prices. Furthermore, businessmen competing for labor in tight-supply markets will not hesitate to grant wage increases which raise costs and lead to further price increases.

Unquestionably, then, much of the postwar wage rise must be viewed as a product rather than a cause of inflationary pressures. What to many businessmen, and some editorial writers, appeared as the constant wage push of collective bargaining was in a large measure a reflection of the pull of the community's demands for goods and services. But this is certainly not the whole story of the upward trend of prices and wages. In a complex economy one is more likely to encounter interactions rather than one-way causal relationships. The unions must not be singled out for special blame. But, considering their numerical strength and heavy concentration in manufacturing, construction and transportation, it would be surprising if they were merely a passive agent in the mechanics of creeping inflation. And indeed, there are good reasons to believe that, given the highly favorable economic environment of the postwar period, collective bargaining has been a contributing factor to the inflationary trend.

(a) Under conditions of slowly rising prices collective bargaining speeds up the adjustment of wages to the rising price level. Perhaps this would not have happened if inflation had been very drastic and current wages would quickly lose their purchasing power. Under such conditions, union contracts setting wage terms for a fixed period of time might actually slow down the adjustment. But this has not been the situation in this country. When prices rise slowly, unorganized workers are not likely to be as alert to the phenomenon as professional union officials whose reputation and position depend partly on their ability to make gains for the members. Accordingly, collective bargaining contracts, covering four million workers, have incorporated wage escalator clauses which tie wage rates to the consumer price index; other contracts have included wage reopening clauses. Wage adjustments resulting from these arrangements usually spread to the unorganized sector as employers attempt to ward off unionization or reduce turnover in their plants.

Union officials consider it their task to protect the economic position of the members. And they would not deny that their goal is to eliminate the potential lag between wages and prices. But though their position may have considerable merit on ethical or other grounds, the fact remains that the rapid adjustment of wages to prices contributes to the inflationary trend. On the one hand it increases the purchasing power of the public; on the other hand, it gives more stimulus to further price increases under conditions of continuing high demand.

(b) Unions will also generally behave differently from unorganized workers in periods of continuous prosperity, which is still not strong enough to exert an upward pull on prices. Over a period of years union members have become accustomed to yearly wage increases; union officials are always under some degree of pressure to "deliver." If the businessmen feel confident that prosperity will continue, either because of governmental action or for other reasons, unions can in many cases negotiate wage increases which lead to higher prices.

This is particularly likely to happen in the strongly unionized, mass-production industries - steel, aluminum, automobiles - in which price competition is very limited. Prices in such industries can be set without regard to short-run market conditions. To protect what is considered the accepted rate of return, increases in cost can be passed on to the buyers. If there are no prospects of a prolonged economic downturn, relatively little resistance will be offered to union demands. Indeed, wage changes may be used as a rationalization for upward price adjustments which exceed increase in costs resulting from new contracts.

Again we must emphasize that if prosperity continues unrestricted by monetary or fiscal measures, such wage and price changes will spread throughout both the union and nonunion sectors of the economy.

(c) Collective bargaining makes its most significant contribution to the continuation of an inflationary trend during periods of economic downturn. As a rule union wages are very rigid downward. Wage rates and benefits negotiated during prosperity are not likely to be reduced during recession, unless the unionized employer is willing to risk a prolonged shutdown of operations. While this characteristic of union wages is not a new phenomenon, it has gained in importance with the widespread coverage of collective bargaining and the increased sensitivity of non-union employers to the trends of union wages. Prior to World War II virtually every downturn in the economy witnessed some drop in workers' earnings. But this has not happened during the postwar period. In fact, hourly employee compensation rose during every one of the three recessions since the end of the war.

This phenomenon must be attributed to the influence of collective bargaining. In some union establishments workers merely held on to the previously negotiated wage rates. But in many establishments they actually gained in wages, benefits or both. To some extent the wage increases were a result of multi-year contracts which prescribed yearly wage raises. In a great many cases, however, they were part of new contracts negotiated during the recession. For example, during the recent downturn an overwhelming majority of new contracts provided for a wage hike. Significantly, these wage changes spread also to the unorganized sector of the economy.

The wage increases that took place during recessions indicate, of course, the strength of American unionism. But they also reflect the essential fact that the business community has considered recession only a temporary phenomenon. It was clear, particularly during the recent downturn, that if the recession continued, strong fiscal measures would be taken to restore full employment.

The behavior of wages during the recessions has contributed to the long-run inflationary tendency of the economy, The least that wage increases in recession periods do is to limit the possibility of price reductions. To be sure, in the basic manufacturing industries, in which price competition is very limited, such reduction would never come anyway, unless public pressure increased more markedly. But wage increases - even when they only match productivity advances - give management a justification for maintaining stable prices in the face of reduced demand and production cutbacks. And as the steel firms demonstrated, wage hikes can be also used to rationalize uniform price increases in an industry which utilized less than 60 per cent of its capacity.

The impact of these various forces - business confidence in the upturn, limited price competition, union-induced wage increases - was reflected in the behavior of prices. During the 1953-54 recession prices were stable; during the recent downturn they actually went up. This experience suggests that in the present economic environment recessions cannot be counted on to reverse the upward trend of price. And since some price increases are likely to take place during expansions, every upturn in the economy will start at a higher price level than that of the previous recovery. This means, of course, at least some degree of inflation. Thus, in so far as collective bargaining contributes to price stability in recessions it constitutes also a force contributing to a long-run inflationary trend.

III.

WE must conclude then that the influence of collective bargaining has been an active force in price inflation. But it is worth reemphasizing that this influence could have been exerted only through interaction with other forces which created an inflationary bias in the economy - the postwar expansion of aggregate demand, stimulated and facilitated by expansion of credit; government monetary and fiscal policies related to the maintenance of full employment; the ability of management in the key unionized industries to disregard short-run market conditions and to pass on the cost of wage increases to the buyers. These factors provided an environment in which unions have been able to push for higher wages against relatively limited resistance of employers, and without incurring serious risk of unemployment among their members. Under such conditions, individual labor organizations - no matter how socially responsible - must be expected to try and to succeed in winning wage concessions which contribute to an inflationary trend.

Our experience with the creeping upward trend of prices has probably been too short to permit firm conclusions about future prospects of the economy. The period has been too much affected both by results of World War II and the Korean war boom to represent what may be thought of as the "wave of the future." But even so, as we examine the postwar mechanics of price- and wage-setting under conditions of high prosperity, one conclusion suggests itself strongly: If the monetary and fiscal measures keep the economy in a virtually constant state of full employment, an "administered inflation" is a possibility that must be reckoned with.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"The Nasties Upset Since Bunker Hill"

February 1959 By COREY FORD '21h -

Feature

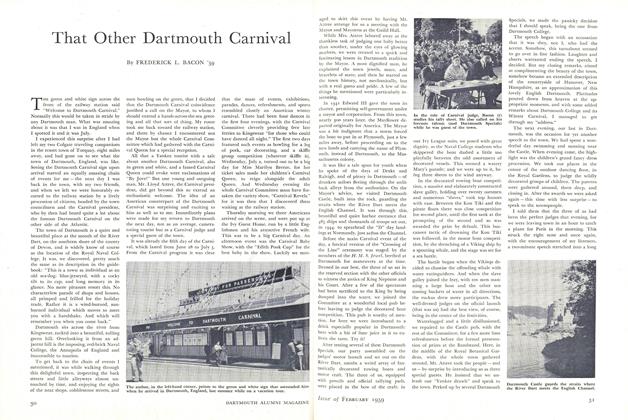

FeatureThat Other Dartmouth Carnival

February 1959 By FREDERICK L. BACON '59 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Dinner Honors Football Team

February 1959 -

Feature

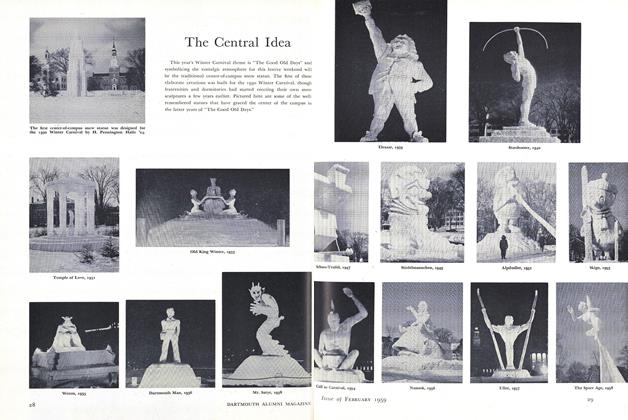

FeatureThe Central Idea

February 1959 -

Article

ArticleSome Consequences of Inflation Psychology

February 1959 By COLIN D. CAMPBELL, -

Article

ArticleInflation: Retrospect and Prospect

February 1959 By GEORGE E. LENT,

MARTIN SEGAL

Article

-

Article

ArticleREVIVAL

October 1936 -

Article

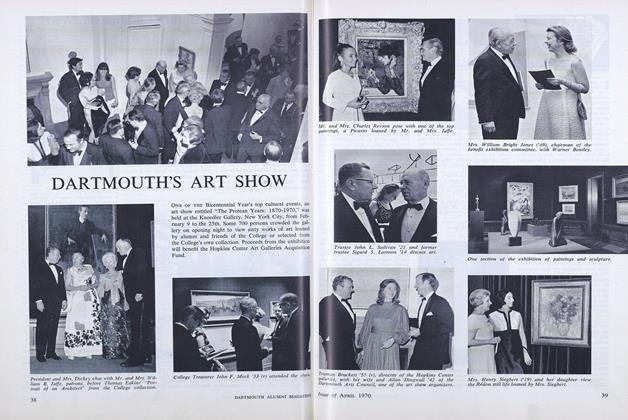

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S ART SHOW

APRIL 1970 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

DECEMBER 1958 By HARRY W. SAVAGE '26 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

March 1944 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

APRIL 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59 -

Article

ArticleA Day at Vassar Sixty Years Ago

FEBRUARY 1932 By J. R. Willard '67