WHEN one of the American forwards missed a flying tackle and plunged headlong into the sidelines, during the Old Millhillians match at Headstone Lane, he knocked the dignified ex-president of the English Rugby Union off his shooting-stick perch and deposited him unceremoniously in the mud. This, spectators agreed resignedly, was just another example of what had been going on here lately. Ever since these touring Dartmouth College ruggers had burst almost unheralded onto the British rugby scene, they had been bowling over the best opposition and leaving their victims sprawled on their hunkers on the soggy English turf, dazed and still a little incredulous.

In the beginning the London sportswriters had been inclined to smile tolerantly at this brash Yankee team ("side" one calls it over here, you know) which had arrived to beard the British lion in his own den. The crew-cut collegians from Hanover, N. H., won their opening game ("fixture", that is to say, old chap), and the startled Daily Sketch admitted: "Tough, these Americans." Two victories later, when the visitors defeated the favored Harlequins by 20-8, the DailyMail warned its readers that "their tackling was deadly, they fell on the ball fearlessly, and their three-quarters ran straight and hard." When the novices from the States shellacked the highly-touted LonDon-Scottish Richmond side 16-3, the Daily Telegraph threw its hands in the air: "The British are not unused to rude reverses, but this victory of an American Rugby XV must be considered one of the nastiest upsets since Bunker Hill."

There'll always be an England, of course, but it may never be quite the same again after the historic invasion of these nineteen husky stalwarts from Dartmouth - the first American rugby team to visit Jolly Old since the game originated here 135 years ago. The team represented another first: they were the initial athletic unit to travel abroad under the banner of President Eisenhower's People to People Sports Program. What they lacked in finesse, they more than made up for in tackling power, in conditioning, in sheer do-or-die. They wound up their two-weeks tour with five wins out of seven games; and the British loved it.

"I have just bought a round of best bitter for Al, Jake and the other 'guys'," wrote John Bromley in the Daily Herald, "to celebrate beating our leading Old Boys' sides at England's traditional sport." "Even with no bands headed by high-stepping drum majorettes to lead them forth," the London Times reported, "no cavorting cheer-leaders to exhort wildly partisan and well-fortified alumni in their support, Dartmouth played with immense zest and determination." The Communist Daily Worker conceded grudgingly that the Americans "demonstrated above-average competence in most phases of the contest" and the Daily Express summed it up: "Now British Rugby knows the worst - Americans can play our game."

More to the point was the plaintive comment of a mud-caked and battered member of the Hongkong-Shanghai Bank side, which had just absorbed an 11-3 beating at the hands of the Yanks. Victors and vanquished alike were sharing a twenty-foot-square bathtub in the locker-room at New Beckenham, soaping each other's backs and steaming out their mutual aches in the murky water. One of the defeated ruggers peered through the steam at his American opponent seated across the tub. "I mean to say, old chap," he sighed, "why didn't you give us some sort of warning?"

WELL, the Dartmouth ruggers can answer that. They didn't have any warning, either. The trip was confirmed on such short notice, in fact, that the team left from final exams direct to the

airport, minus two suitcases and one player (he caught up with his teammates later by police escort), and they were still inflating their rugby balls as they drove to Boston to board the Pan American Clipper for London. Just in case you happen to be planning to forward a rugby team to England sometime, here's the inside story of how it all happened.

Not that the English trip was any sudden decision. Ever since the game of rugby had started at Dartmouth, back in 1953, we had been dreaming of an overseas tour. I use the ,word "we" advisedly: for my house adjoins the Dartmouth campus, and in the course of time it has become the unofficial Rugby Club headquarters. The playing field is only a block or so away, and after each game the Green team and their opponents clatter down the street to my house, festooning my lilac bushes with cleated shoes and wandering onto the lawn to enjoy barbecued hot dogs and the traditional keg of victory. My own rugby experience is limited to a few scrums conducted in the New York subways at rush hour; and my value to the team lies in the fact that I know so little about the finer points of the game that I never bother them with advice. So it was in my living-room that the plans for the trip to England were hatched.

This was the year for it, we all agreed. Our fall season had been completed with a total score of 89-0, giving Dartmouth the mythical Eastern title, and now, with the end of football, the team had been augmented by four star members of the Big Green's Ivy League champion squad. As an added incentive, Eddie Eagan, chairman of the People to People Sports Committee, had invited the Dartmouth ruggers to initiate his new program which, in President Eisenhower's own conception, is "dedicated to the promotion of international sports exchange on the premise that when good sportsmen get together mutual understanding and friendship are broadened and the prospects for peace are enhanced." The problem was how to raise the money.

The Dartmouth Rugby Club, like most American rugby groups, is self-coached, and self-financed. Many of the players are on scholarship, and working their way through school. The College's limited athletic budget could not be tapped. Bit by bit, nevertheless, donations began to come in. Loyal Dartmouth alumni and rugby enthusiasts sent in personal checks to help defray expenses. Pan American helped out; so did Eddie Eagan's Committee; the editors of Sports Illustrated agreed to turn over the proceeds of this article to swell the kitty. Team-members pawned watches and rings in order to make their contributions to the cause.

Still we were far short of the required total, and time was running out. Dick Liesching '59, a scholarship student from England and president of the Dartmouth Rugby Club, had cabled to his father, R. R. de L. Liesching of Surrey, to arrange a tentative series of fixtures with English clubs; and the team had secured their State Department passports, just in case. On a gloomy Saturday night - little more than a week before the first scheduled game in England - the team met in my living-room and decided we could not keep our British hosts dangling any longer. Tomorrow would have to be the deadline. Cables and trans-Atlantic phone calls went on all night, and the deadline was advanced to Monday, and then to Tuesday. Orton Hicks '21, vice-president of the College and a devoted friend of the ruggers, was working feverishly to find some last-minute solution. Wednesday noon was set as the positively last moment.

At eleven-thirty that morning, Dartmouth alumnus Sigurd Larmon '14, chairman of Young & Rubicam, agreed to make up the financial difference; and the long-awaited bulletin was posted on the door of the Beta house for all the players to see: "We're on our way to England. Get your smallpox shots." Long-distance phone calls broke the news to parents that their sons wouldn't be with them this Christmas; several players who had already started home for the holidays were hauled back to Hanover in frantic haste; dates converged on the Dartmouth campus for tearful farewells. Dick Liesching woke his father in Surrey at three a.m. with the good news. "Of course," Dick added, a little afraid that after all the team might not be up to British expectations, "we're really not world-beaters, you know, father."

"Just so long as you know the basic rules," Mr. Liesching senior consoled him, "we should have a lot of fun."

They knew the rules. Twenty-four hours after they landed in London, they took on their first opponents, an experienced Haslemere side. Score: Dartmouth 12, Haslemere o.

THEY made their entrance," reported the London Times, "with all the bounce and, at the same time, the endearing humility of Pooh's great friend Tigger." When they stepped from the Clipper in London, groggy and still shaky after their abrupt departure, Captain John Hessler of the Green Rugby Team made a modest statement to the press. "We have come here to increase our knowledge of the game," he assured them. "We have more to learn than to give." The press remembered it. When the tour was over, a sportswriter observed pointedly: "The 'learners' have become the 'professors'."

For the first night the team was quartered with Mr. Liesching and other English friends in the Surrey countryside; and Jake Crouthamel, all-Ivy League star half-back from the football squad, had his first taste of British hospitality when he was served a brimming stein of beer in the bathtub. Charles Goldsmith, Dartmouth '29 and now an MGM executive in London, enlisted support among other alumni overseas, and the team moved to comfortable diggings in the heart of London. After their first appearance at Haslemere, British rugby enthusiasts rallied to their aid. Dr. P. S. d'Cabot, co-founder of the Eastern U.S.A. Rugby Union and now its British representative, became their English sponsor, and Jerry Jenkins, a former Cambridge Blue, volunteered to help as coach. "That's one example of British sportsmanship we'll never forget," John Hessler said. "They weren't so much interested in winning over us as they were in helping us to be a better rugby team."

Now under expert tutelage the technique of the Yankee invaders began to improve fast. The Americans learned to conserve their strength, not to run themselves out. They learned to play a position-type game, instead of their former style of hustling and wide-open pursuit. They learned to bind lower in the scrum. They learned to slip the ball from the line-out.

They were learning other things about British rugger customs. When an opposing player was felled by a hard tackle, and had to be assisted off the field, Dartmouth prop forward Mike Mooney generously applauded the downed player. He was reminded severely that one doesn't do that over here, old boy; only when a player recovers and returns to the game is he applauded. "They thought I was cheering because the other team had lost a player," Mooney sighed later. "It was really very trying."

The British were learning about American customs, too. Particularly were they startled when the Dartmouth team indulged in warm-up calisthenics before a game, football fashion, doing knee-bends and pushups and breaking from a huddle with a loud Yankee cheer. The London Telegraph reported to its readers about these strange American tribal rites: "Their impressive preliminaries comprised a series of exercises, performed in a circle and ranging from press-ups to a painful contortion which the military would be pleased to call 'alternate toetouching.' These completed, a short conference was held, the group eventually breaking up with a fierce war-cry."

Equally baffling to the British hosts were the exhortations of the American partisans in the sidelines, including such Yankee words of encouragement as "How to go, gang!" or "Heads up, Green!" or "Come on, baby, let's go!" These shouts, ringing out above the occasional discreet "Well played indeed!" from the other side, produced some frowns among British spectators. Even more distressing was the frequent American yell of "Hit 'em!", which was interpreted as an open incitation to mayhem. "Not quite our regular procedure, I mean to say," a tight-lipped Briton remarked to me.

London was growing used to strange sights. Nursemaids with perambulators and Englishmen with folded umbrellas paused to stare in frank disbelief at the daily workouts in Hyde Park, where a score of bulky figures in green Dartmouth jerseys and sweatpants were practicing scrumdowns on the hallowed site of political oratory. Pedestrians gazed open-mouthed as a chartered bus rolled down Piccadilly, filled with Dartmouth ruggers, while Jake Crouthamel perched atop a pile of gear in the front of the bus and taped the shaved ankles of his teammates on the way to the next game. Even the size of the players was a source of considerable consternation. The Express commented that "they range from large to very large", and Al Krutsch, Dartmouth football captain and all-Ivy guard, was described by one sportswriter as "a caterpillar tractor, only more mobile." The close-cropped American skulls seemed to fascinate the journalists, and the press referred to Tony Denton, a British-born student at Dartmouth and the Green's scrum-half, as "a solitary and comparatively long-haired Englishman among the crew-cuts."

But inevitably these first startled impressions gave way to a deeper understanding. Ambassador Jock Whitney, after receiving the Dartmouth team, wrote them: "This venture you have undertaken is, in itself, an excellent contribution to the growing ties between British and American people. And your fine showing is a credit to your college and your country. Looking at the results of your efforts here, you are painting the town green." Prince Philip sent a warm telegram of congratulations and good wishes. The Earl of Dartmouth, for whose family the College was named, appeared in person to offer his greetings to his New Hampshire namesakes. And Field Marshal Montgomery, shaking hands with the American players after a match, was asked how he felt about seeing a Yankee team beat the British at their own game. "Jolly good," he said. "Makes us sit up, you know, keeps us from getting too complacent. Jolly good indeed."

You could see the change all over London, as the tour went on. Passersby, recognizing the crew-cuts, shouted "Good luck Yanks!" or "I see you rubbed the Old Boys in the mud!" Shopkeepers offered special rates for the visitors, and one Dartmouth rugger spent the better part of an evening trying in vain to be allowed to pay for his own beer in the neighborhood pubs. At the Savile Club an elderly member, informed that rugby was also played at such Ivy League schools as Yale and Harvard, pondered thoughtfully: "Harvard? Harvard? Oh, yes, isn't that somewhere near Dartmouth?" Children stopped team-members on the sidewalk for autographs; and when they appeared at Richmond for their final game, the louder shouts were for the American side: "Well played indeed, Daht-muth!" Even the U. S. Air Force band, which had arrived from a nearby American Air Base to shatter English tradition by serenading their countrymen, was invited to march out onto the field between halves, where they rendered "Has Anybody Seen My Gal" amid enthusiastic cheers.

And when the visitors upset all the experts by taking Richmond 16-3, the losing side, following British rugby tradition, formed a double line and applauded the mud-smeared Yankees as they walked to the lockerrooms; and then walked through a double line of Yanks, who applauded the losers in turn. You felt that a lot more had been learned than rugby, in a couple of short weeks. "We learned about sportsmanship over here," Al Krutsch said solemnly, "and we learned humility." You felt the experience would not be forgotten by either side.

So that night the weary Dartmouths boarded the Pan Am Clipper for the States, wearing English club-ties which they had exchanged with their hosts, sporting black bowler hats, even carrying a huge guitar purchased (at a discount) in Soho. When the airplane stewardess started her usual explanation about how to put on a Mae West, the team solemnly chanted an English rugby song they had learned from the Millhillians:

"Why was she born so beautiful, why was she born at all?

She's no bloody use to anyone, no bloody use at all."

Sam Bowlby glanced at his team-mates in disgust. "Still trying to improve Anglo-animal relations," he commented, and closed his eyes.

The tour was over. They had successfully carried the banner of the President's People to People Program, as its first emissaries abroad. They had won an impressive Victory; they had won an even more lasting friendship. Now the nineteen American ambassadors settled down in their seats, to catch a little shut-eye on the way back across the ocean. Classes would be starting in Hanover tomorrow.

SPRING vacation, March 20 to April 1, will find the Dartmouth Rugby Club in California for a series of matches. The trip to the West Coast will replace the annual jaunt to Bermuda for the College Week matches, in which the Green ruggers have been outstanding for several years. The California itinerary is not complete, but matches with the strong U.C.L.A. and Pomona teams are definitely scheduled.

Having realized one dream with the trip to England, the Dartmouth Rugby Club is now working up another: a clubhouse of its own where it can have its headquarters and play host to visiting rugby teams, in the British fashion. Such a clubhouse is envisaged as making the ruggers a sort of athletic society.

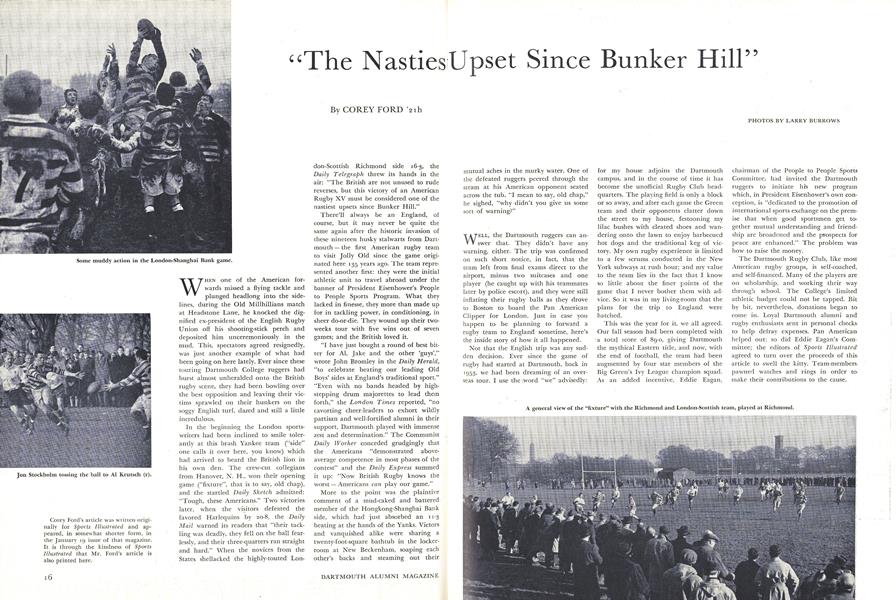

Some muddy action in the London-Shanghai Bank game.

Jon Stockholm tossing the ball to Al Krutsch (r).

Customary after a rugby match in England is entertainment of the visiting team in the host team's clubhouse. Here the Dartmouth ruggers are guests at a tea given by members of the Hong Kong-Shanghai Bank team, which was defeated by the Green.

Darts and English ale provided additional post-game entertainment.

John Edwards '61 waves the London bowler he adopted as his headgear upon arrival.

Captain John Hessler '59.

Roli Kolman '60 gets sideline sympathy for a bloody noggin sustained in a hard scrum.

Football tackle Sam Bowlby '60.

In contrast to the Edwards derby, a Sherlock Holmes hat was Jon Stockholm's choice.

Al Krutsch '59, muddy but unbowed.

The Earl of Dartmouth greeted the team at an alumni party in London. L to r: floor - President Dick Liesching, Captain John Hessler; ler; row - Al Brown, Mike Miller, Charlie Goldsmith '29, Lord Dartmouth, his son Lord Lewisham, Jake Crouthamel, Al Krutsch, Bill Gray, Corey Ford; back row - Mike Mooney, Roli Kolman, Sam Bowlby, Dave Bathrick, John Edwards, Dave Farfan, Dana Johnson, Earl Glazier. Not shown: Art Cockburn, Joe Graham, Tony Denton, Jon Stockholm.

Ambassador John Hay Whitney greets the team at the U. S. Embassy in London,

Dartmouth alumni in the London area were hosts to the Rugby Club at a dinner.

Corey Ford's article was written originally for Sports Illustrated and appeared, in somewhat shorter form, in the January 19 issue of that magazine. It is through the kindness of SportsIllustrated that Mr. Ford's article is also printed here.

Corey Ford, the nationally known author, whose article about the rugby trip makes such good reading in this issue, is the father confessor and patron of the Dartmouth Rugby Club in multifarious ways. Among other things, his large Hanover home is hardly his own any more. And a sizable part of the funds raised for the trip to England came from his Sports Illustrated article fee, which was turned over entirely to the Rugby Club. Mr. Ford, an adopted member of the Class of 1921, set up bachelor quarters in Hanover in 1952. He serves as adviser to student writers and publications, and has befriended Dartmouth's boxers and wrestlers as well as the ruggers. What was once a squash court in his home at 1 North Balch Street (originally owned by architect J. F. Larsen) has been converted into a small gymnasium, off which showers and a locker room have been installed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThat Other Dartmouth Carnival

February 1959 By FREDERICK L. BACON '59 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Dinner Honors Football Team

February 1959 -

Feature

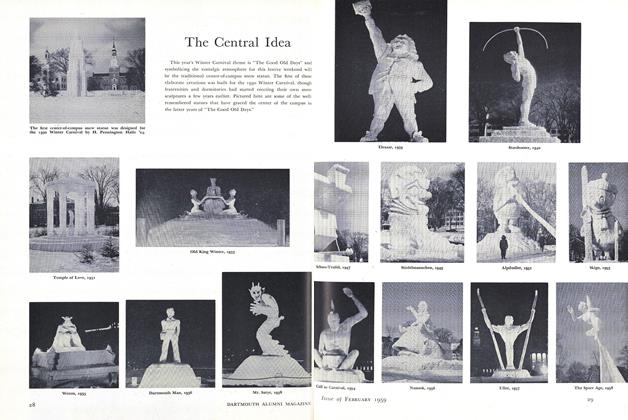

FeatureThe Central Idea

February 1959 -

Article

ArticleSome Consequences of Inflation Psychology

February 1959 By COLIN D. CAMPBELL, -

Article

ArticleShould We Blame the Unions?

February 1959 By MARTIN SEGAL -

Article

ArticleInflation: Retrospect and Prospect

February 1959 By GEORGE E. LENT,

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Transcending Great Issues

OCTOBER 1969 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Vote to Consider Associated School for Women

MAY 1971 -

Cover Story

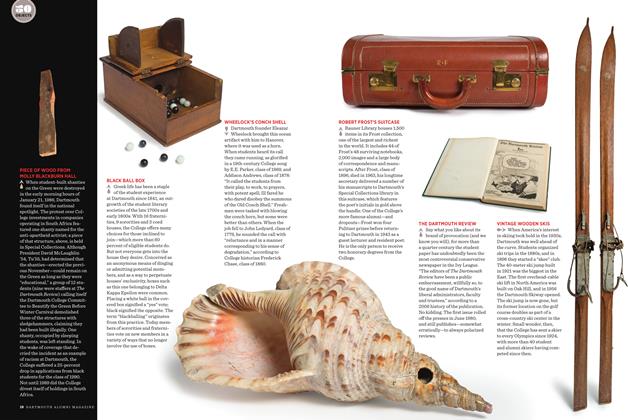

Cover StoryBLACK BALL BOX

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

JUNE 1971 By B.B. -

FEATURES

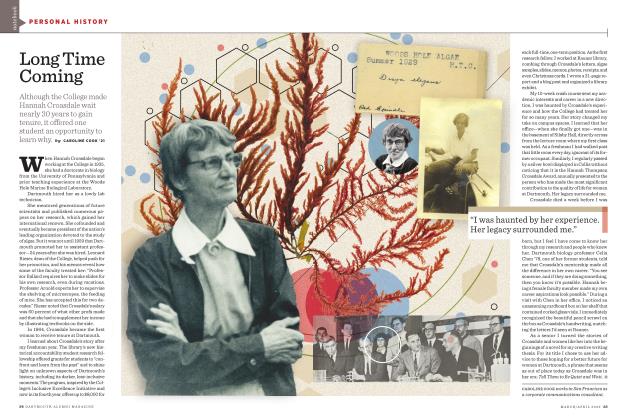

FEATURESLong Time Coming

MARCH/APRIL 2023 By CAROLINE COOK ’21 -

Feature

FeatureMaking Ambitious Ends Meet

APRIL 1988 By Deborah Solomon