ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ECONOMICS

A RECENT development in the American economy is the general acceptance of the belief that inflation is inevitable. Just as the long depression in the 1930's resulted in a generally pessimistic outlook and the fear that our economy would again be faced with mass unemployment, so the experience with steadily rising prices during the past two decades has led the majority of die people to believe that prices will continue to rise. From 1939 to 1958 prices in the United States have more than doubled. The experience with inflation has been an extended one, and the public seemingly has become resigned to price increases as a long-term tendency. Chairman William McChesney Martin of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System has frequently expressed concern over this prevailing notion that creeping inflation is inevitable.

Some persons regard continuous inflation - even if it is gradual — as a force that may undermine the economy. Others consider gradual inflation as a necessity if unemployment is to be kept low and the growth of output is to be maintained at high levels. Probably the three most common misconceptions about continuous inflation are: (1) the tendency to exaggerate the redistribution of income from creditors to debtors and from wage earners to entrepreneurs caused by inflation; (2) the fear that continuous inflation will lead to monetary collapse and the resort to barter trade; and (3) the belief that rapid inflation results eventually in the inconvenience of having to use large quantities of currency to make small transactions - for instance, a basketful of paper money for a loaf of bread. But these claims about inflation cannot be substantiated by recent experience in China, in South Korea, and in many other countries. The very rapid inflations in China between 1937 and 1949 and in South Korea from 1945 to the present provide us with some useful experience with conditions of anticipated inflation continuing over more than a decade in each country. An analysis of events there shows that these countries did adjust to continuous and rapid inflation, but that there were many real problems in making the adjustment.

Common Misconceptions

The dangers usually attributed to inflation are based on the assumption that the rise in prices is unexpected or that persons are unable to adjust to it. It is only under such conditions that debtors gain in comparison with creditors, and entrepreneurs in comparison with wage-earners. If inflation is expected and persons are able to adjust to it, the incomes of wage-earners, owners of rental property, and creditors usually lag only a little behind the rise in prices, and entrepreneurs, stockholders and debtors do not receive unexpected gains.

When inflation is expected, financial institutions and persons who lend money typically protect themselves by charging higher rates of interest. If prices are expected to rise 3 per cent per year, for example, a 6 per cent interest rate on a money loan is equivalent to a 3 per cent rate when prices are stable. During South Korea's rapid inflation that started in 1945, unregulated interest rates have been as high as 20 per cent per month; and Korean borrowers have been willing to pay such high rates because they expect that inflation will enable them to do so. In the United States interest rates of all types have risen since World War II. The maximum rate of interest that commercial banks are allowed to pay on savings accounts was raised from 2½ to 3 per cent in January 1957. While some series of United States Savings Bonds yielded only 2½ per cent during World War II, all series now yield 3¼ per cent. An important reason for this rise has been the heavy demand for loanable funds, but anticipated inflation is also involved.

A common method used by wage-earners to protect themselves against inflation is to include in the wage contract a provision that wage rates vary automatically with the government's cost-of-living index. Because it takes some time to gather statistical data on the cost of living, workers will usually still lose a little, but the loss may be small. In Nationalist China between 1937 and 1949 the annual rise in prices was for some years as much as 200 per cent, and wages of all government employees were adjusted daily to a cost-of-living index. In the United States many labor unions have recently included escalator wage clauses in collective bargaining contracts. Under such clauses, wage rates are increased when the monthly consumer price index rises. In 1952, 3½ million out of 15 million union members were covered by contracts of this type. The number of persons under such contracts declined between 1952 and 1955 when prices in general were stable, but it has increased again during the past few years.

These attempts by individuals to protect themselves from the effects of inflation tend to eliminate the stimulating effect of slowly rising prices on economic output and growth. When costs lag behind prices, rising prices will raise profit margins, giving enterprises both (1) a bigger incentive to raise output and to add to capital and (2) the means to finance the capital needed. When interest and wage costs do not lag, gradual inflation no longer has these stimulating effects.

A common error is the belief that continuous inflation eventually develops into a flight from money with inevitable monetary collapse. American economic advisers were shocked by the rapidity of inflation in South Korea following World War II and usually predicted such a breakdown. Despite these fears, the monetary system in South Korea has not yet collapsed, and there has been a remarkably small increase in barter trade. In South Korea and in many other countries in which the public has expected inflation, people have used their depreciating money rather than trade by barter because of barter's extreme cumbersomeness. The reason for the use of barter during the German inflation after World War II was that price controls that suppressed inflation made barter an effective - although illegal - way of evading price controls. During the South Korean and Chinese inflations inducements to use barter as a method of evading general controls over prices did not exist because there were few effective controls of this type. In the United States today there is little danger of a breakdown in the monetary system. The disadvantages of barter would far outweigh the disadvantages of using a gradually depreciating medium of exchange.

In countries in which rapid inflation is anticipated, the velocity of money (the number of times each dollar, pound, or franc is spent per year) is usually very rapid. The normal pattern is for velocity to increase sharply when the public first begins to expect continuous inflation and then to continue at a high level. In the United States during the past decade there has been a significant increase in the velocity of money even though no sudden rise in velocity has occurred. From 1948 to 1958 the annual rate of turnover of demand deposits rose over 80 per cent in New York City banks and approximately 40 per cent in other cities. Also, the ratio of the national income to the total volume of currency plus demand and time deposits - income velocity - has risen, even though for many decades prior to World War II the long-run trend of this ratio was downward.

Another common error is the belief that continuous inflation results in an excessive bulkiness of the money supply. During the Chinese inflation, reports of the use of wheelbarrows for carrying money were common. Although the use of the old small-denomination bills would be cumbersome as inflation progresses, in Nationalist China the use of such bills was usually unnecessary because the government continuously issued notes in larger denominations. As prices rose, the public exchanged the old small-denomination bills for the new larger-denomination bills. In South Korea, although the quantity of money increased almost 130 times from 1945 to 1952, the number of paper notes in circulation only tripled.

Some Problems of Adjusting to Inflation

There are disadvantages to the economy as a whole, to businesses, and to individuals caused by conditions of continuous inflation. Not all these disadvantages are found in an inflation as slow as is expected in the United States.

In countries in which the public anticipates rapid inflation, people usually hoard goods, coins, and foreign currency. When money does not keep its real value, these assets may become preferable to money as a source of protection in time of emergency. Hoarding of commodities has the disadvantage of causing such goods to be held in reserves instead of being used in production. Also, in the Chinese inflation, production costs were often increased by careless buying because it was the normal practice of businessmen when they sold something and acquired currency to rush out to lay in more stock. When a loan was repaid unexpectedly, even a bank would purchase commodities to avoid holding an excessive amount of currency. In countries in which no more than a gradual rise in prices is expected, the unavoidable risks and storage costs of hoarding commodities would undoubtedly be greater than the loss in the real value of money, and little, if any, hoarding would occur. It is hard to find goods that offer perfect protection because prices of hoarded goods do not always fluctuate exactly as prices in general. During 1956-57, for example, when prices in general in the United States were rising, prices of many metals - which are frequently used as hoarded commodities - declined, and hoarding of metals would have offered less protection than money.

Although persons and business firms can to a certain extent adjust to conditions of expected inflation, the widespread belief that inflation is inevitable creates several sources of instability in the economy. Particularly disturbing results occur when the rate of inflation turns out to be less than expected. Because the Federal Reserve System and the Federal government cannot control the rate of inflation precisely, the danger of a lower rate of inflation than expected is always present. Under such conditions a sharp decline in stock prices or farm land values could occur if investors who bid up prices to high levels based on anticipated inflation are disappointed. A stock market crash contributed to the severity of business depressions in 1884, 1893, 1907 and 1929, and the stock market is today a large enough influence in our economy to be of considerable concern. The effect is not only psychological, but the fall in stock values may have a generally depressing effect on spending. A sharp decline in farm land values would also aggravate a general business contraction by creating problems in agriculture.

Then too, if inflation is less than expected, persons and business firms that have incurred debts at high rates of interest discounting inflation will find the debts more burdensome than expected, and some of them may be forced to default. Some business firms miscalculate their ability to meet debt commitments even when prices are stable. But the risks due to a lower rate of inflation than expected are an additional source of uncertainty, and a slowing up of the rate of inflation would probably affect a large number of debtors simultaneously. The increased uncertainty would also probably discourage capital investment financed with borrowed funds.

An example of extreme instability caused by changes in the rate of inflation occurred in Communist China following the defeat of the Nationalists in 1949. Although such disastrous effects would not occur with gradual inflation, this illustration helps to show the risks to lenders and borrowers created by changes in the rapidity of inflation. Between 1937 and 1949, the Chinese Communists, the Japanese in China, and the Chinese Nationalists financed their government operations primarily by printing money. The Communists had thus learned from experience, and partly by recalling their own propaganda about the Nationalists and the Japanese, that price stability required limiting the quantity of money. They were unaware of the difficulty of administering a smooth transition from an economy adjusted to continuous inflation to one based on price stability. In 1949 the Communists twice tried unsuccessfully to stop increasing the money supply. Both attempts stabilized prices for a short time, but then were followed by explosive inflations as soon as the populace realized that the money supply was again expanding rapidly. Communist statisticians estimated that in 1949 prices rose more than 7,000 per cent. These attempts at stabilization were more upsetting to the business community than the steady depreciation to which the Chinese had become accustomed during the previous decade. Lenders lost heavily when they lent money at low rates assuming erroneously that prices were going to be stabilized. Borrowers were ruined when they borrowed money at high rates assuming erroneously that prices were going to rise rapidly. The monetary policies of the Communist government during its first year in control of mainland China wiped out so many lenders, bankrupted so many businesses, and resulted in such extreme uncertainty that they were a major factor in breaking the power of the business groups.

If the rate of inflation is very rapid, business accounts must be adjusted in some manner. A device used by the Chinese Communists was to require all businesses to keep their accounts in terms of units of corn flour. Their newspapers published the current price of corn flour, and all wages, debts, taxes, and other costs were then paid in Communist currency at a price determined by multiplying the cost in units of corn flour by the current price of corn flour. Even gradual inflation has significant implications for certain established accounting practices and tax policies in the United States - particularly the carrying of assets at their historical cost rather than at current replacement cost and reckoning depreciation on this basis. Present policies based on assets valued at historical cost may result in exaggerated profits and larger corporate income taxes than would otherwise occur.

Anticipated inflation usually means that individuals must find suitable "hedges against inflation." Activity in the stock markets of the large Chinese cities expanded rapidly between 1937 and 1949, even though the precarious political condition of the Nationalist Chinese government was well understood by the Chinese public, and it was known that the Chinese Communists would expropriate private corporations if they took over. During much of this period, prices of corporation stock in China rose as fast as prices in general. In the United States stock prices, as measured by Standard and Poor's index of 500 common stocks, increased more than three times between 1949 and 1958. Part of this increase reflects a substantial rise in corporate dividends and earnings, but since the average dividend-price ratios of these stocks have fallen from 7 per cent to less than 4 per cent, increased earnings do not account for all of the rise. Even though the Federal Reserve System has raised margin requirements, which are now 90 per cent, these moves have not had any apparent effect on the level of stock prices. Although the demands of political leaders to have a Congressional investigation frequently imply manipulation of some kind, increases in stock prices relative to bond prices have probably been the natural result of the search for protection against inflation.

Between 1948 and 1958 prices of farm land in the United States have doubled even though net farm income declined over 30 per cent from its peak in 1948 to the present. Although such a divergence between current farm income and farm land values is frequently described as "puzzling," a sharp rise in farm land values is what one would expect from the development of a public consciousness of rising prices. There are many reasons for the rise in farm land values including the growing demand for farm land for non-agricultural uses and the trend to enlarge farms, but the desire for an inflation hedge is also one of them.

Another problem created by gradual inflation is the insecurity of the small saver. Similar problems are created for persons with large savings, but such persons are more able to take risks because of the size of their savings. Our financial institutions - insurance companies, savings banks, and the debt policy of the U. S. Treasury - are based almost completely on the assumption that the normal situation is price stability. Under present conditions the small saver is provided a choice between corporation stocks and fixed money claims in the form of insurance policies, savings deposits, and various types of bonds. If he selects the former - including most mutual funds - he runs the risk of receiving no dividends and having to sell his shares for practically nothing if his choice turns out badly or if there is a serious depression. On the other hand, if he selects an insurance policy, savings deposit, or bonds, he runs the risk of having the real value of his savings decline through gradual inflation even though he is assured a fixed rate of return.

There is probably a need in our economy for an insurance policy, bond, or savings deposit which would be repayable in a variable number of dollars, but in a constant amount of purchasing power. For example, if the price level doubles during the life of the bond, insurance policy, or savings deposit, the owner would get back twice the number of dollars he originally loaned or contracted for. The interest payments on such a bond or savings deposit might also vary with the price level, but because of the greater security provided, the rate of return would probably be considerably less than currently available. Although the Prudential Insurance Company of America has attempted to sell "variable annuities," there are many restrictions in both federal and state laws impeding their efforts, and other insurance companies and the New York Stock Exchange actively support the legal restrictions against the sale of such annuities. The U. S. Government also has done nothing to provide savers with a constant-purchasing-power Government bond, although such bonds have recently been issued and sold in France and Finland. Under present conditions, many small savers in the United States have no way of protecting themselves against insecurity. In periods of depression this loss of individual security would probably be destabilizing.

About the Authors

PROFESSOR CAMPBELL (Harvard '38, Ph.D. Chicago '50) was with the Central Intelligence Agency, 1952-54, and was an economist with the Federal Reserve System, 1954-56, before coming to Dartmouth. He has made special studies of inflation in China and South Korea.

PROFESSOR LENT (R.P.I. '34, Ph.D. Columbia '47) is Director of Research at Dartmouth's Tuck School of Business Administration, as well as Visiting Professor of Business Economics. He formerly was on the tax advisory staff of the Treasury Department in Washington, and also served in the comptroller's office of the Department of Defense.

PROFESSOR SEGAL (Queens '48, Ph.D. Harvard '53) has taught at Harvard, Columbia and Williams and has been consultant to the Senate Sub-Committee on Anti-Trust and Monopoly. He was formerly full-time and is now part-time staff economist with the New York Metropolitan Region Study. His book on the New York labor market is to be published by the Harvard University Press this spring.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"The Nasties Upset Since Bunker Hill"

February 1959 By COREY FORD '21h -

Feature

FeatureThat Other Dartmouth Carnival

February 1959 By FREDERICK L. BACON '59 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Dinner Honors Football Team

February 1959 -

Feature

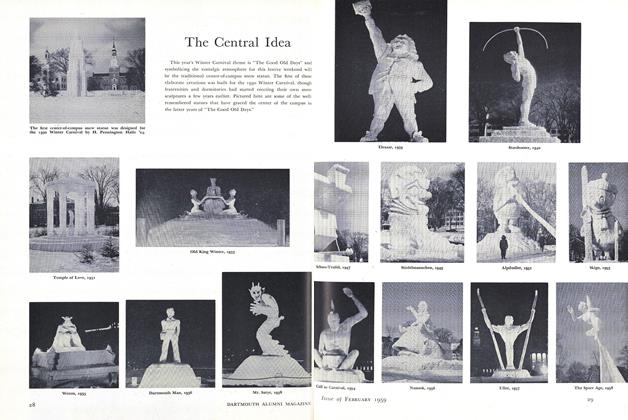

FeatureThe Central Idea

February 1959 -

Article

ArticleShould We Blame the Unions?

February 1959 By MARTIN SEGAL -

Article

ArticleInflation: Retrospect and Prospect

February 1959 By GEORGE E. LENT,