A TRI-MONTHLY SUPPLEMENT TO THE DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE CONTINUING THE EDUCATIONAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FACULTY AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGE Number 2 • February 1959"The real trouble with this world of ours is notthat it is an unreasonable world, nor even that it isa reasonable one. The commonest kind of trouble isthat it is nearly reasonable, but not quite. Life isnot an illogicality; yet it is a trap for logicians. Itlooks just a little more mathematical and regularthan it is; its exactitude is obvious, but its inexactitude is hidden; its wildness lies in wait."- G. K. CHESTERTON

VISITING PROFESSOR OF BUSINESS ECONOMICS, TUCK SCHOOL

OVER the last two decades no economic event has had a greater impact on the daily lives of people than the dollar's shrinking purchasing power. (Professor Campbell discusses the psychology of inflation below). More than two-thirds of the period since 1940 has been marked by rising prices, which have more than doubled the cost of living. While prices have been stable since mid-1958, many believe this is only a temporary lull in a long-run inflationary trend.

About three-fourths of the price rise has been the inevitable accompaniment of World War II and its aftermath, including Korea. But since 1956 the price rise has taken a more subtle form of "creeping inflation," even in the face of recession. There is little agreement on the causes of this recent inflationary experience, and even less agreement on the prospects for holding the price line for the future.

Better perspective on the inflation problem can be gained by a brief review of the major contributing factors over the last two decades. We shall then examine the price prospects for the current year and the possibilities of curbing inflationary tendencies over the long run.

Inflation has been described simply as the condition of "too much money chasing too few goods." (This oversimplified explanation ignores the complexity of the inflationary process, described more fully below by Professor Segal.) In accounting for the price effects of aggregate demand on the limited supply of goods it is convenient to distinguish among "dollars" spent by: (1) individuals, (2) business and (3) government. In the current "cold-war" economy, consumers' expenditures typically account for roughly 65 per cent of total demand; government, 20 per cent; and business investment expenditures, 15 per cent. While we are interested principally in prices of consumers' goods and services, the expenditures of government and business obviously affect the prices of the limited resources available for their supply.

From the consumers' point of view the most useful measure of prices is the Consumer Price Index, compiled by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This is a monthly average of prices of about 300 goods and services ranging from home permanents and razor blades to automobiles and kitchen sinks. The price of each item is weighted by its relative importance in a typical family budget of urban wage-earners. For example, food, liquor and tobacco account for about one-third of the weights; services, 14.4 per cent; housing, 12.7 per cent; clothing, 8.8 per cent; metal products, 10.9 per cent; and public utilities, 5.0 per cent. The index is currently related to average prices during the 1947-49 base period.

During World War II government purchases for national defense swelled to about 40 per cent of total national expenditures. Private consumption was curbed by high taxes and rigid rationing of goods, and after March 1943 price controls were imposed to curb rising prices. But by 1945 the consumer price index increased 28 per cent above its 1938-40 average. Much of the wartime inflation, of course, was not reflected in the price index but was concealed in "black-market" prices and quality deterioration.

Diversion of resources to military requirements left huge postponed civilian demands and a tremendous accumulation of liquid funds to fulfill them. While government expenditures contracted, industry expenditures for new plant capacity greatly expanded. Price and wage controls were abandoned long before goods could be made available in sufficient supply, with the result that by 1948 consumer prices rose sharply to 70 per cent above the pre-war level.

After two years of relative price stability the Korean outbreak, in mid-1950, precipitated another upsurge. By mid-1952 military demands and speculative influences raised consumer prices another 12 percentage points. This spurt was followed by four years of stable prices, when the monthly consumer price index varied no more than 1 per cent from its mid-1952 level.

The rapid business recovery from the 1953-54 recession was followed by a price upturn in the spring of 1956. Under pressure of one of the greatest investment booms in recent history, prices continued to rise for a year after business reached its peak in July 1957. Between March 1956 and July 1958, consumer prices rose 8 per cent, at an average annual rate of about 3.5 per cent. By the end of 1958 the consumer price index stood at 124 per cent of the 1947-1949 average and more than double the 1940 index of 60.

Creeping Inflation, 1956-1958

Because of its implications for the future, the price creep since March 1956 has been the source of great concern. Analysis of this price rise, through mid-1958, may therefore provide a better understanding of the course of future prices.

Since the spring of 1956, price increases were registered in virtually every category. But most notable was the persistent rise in the price of services, which has been almost uninterrupted since the end of the war. Significant advances, averaging 17 per cent, were made in the cost of finance and insurance, largely because of higher casualty and fire losses; amusement admissions rose about 12 per cent; and hospital care about 14 per cent. On the other hand, the postwar rise in rents had slowed down to a crawl - 5 per cent; and the prices of electricity and gas rose about 5 per cent.

Rising food prices have also contributed greatly to the higher cost of living. Prices of all foods increased about 12 per cent over the period; fruits and vegetables rose 17 per cent. Since July, however, food prices have drifted lower.

Durable goods have had diverse price trends. While automobile prices rose about 10 per cent, prices of various appliances such as refrigerators declined.

The upward pressures of an expanding economy generated the wage-price spiral since early 1956. All sectors of the economy contributed: The boom in business capital investment; rising Federal as well as state and local government expenditures; expanding export markets; and, fed by liberal doses of consumer and mortgage credit, consumer expenditures for houses, automobiles and other goods and services. Price adjustments served their historic function of rationing these unusual demands among scarce resources.

Many have been puzzled by the persistence of rising prices following the business downturn in the fall of 1957. While such price lags have accompanied the early stages of other recessions, the strength of the recent rise was unusual. Government payments for unemployment insurance and other benefits sustained a high level of purchasing power, and retail sales, except for durables, actually continued to rise throughout the recession. During this time the prices of services continued to catch up with rising costs. But one of the big factors was the sharp rise in food prices, due principally to lower supplies of fruits and vegetables and meats. While prices of many goods declined, they were more than offset by price rises of other goods and services.

The Outlook for 1959

There is some apprehension that prices will turn up again with the upturn of business. While this has been the historical tendency - subject to some lag - there is little reason to expect more than modest price rises before the end of 1959, despite indications of a strong business recovery. Food prices appear to have reached their peak and are trending downward with bumper crops and increased supplies of cattle and especially hogs. While prices of some services will continue up, they have largely been adjusted to higher costs and should generally level off. Prices of many durable and semi-durable goods should reflect the considerable cost savings resulting from improved productivity - unless these savings are offset by higher wage and other costs. A critical test will be seen this summer when labor contracts in the steel industry are reopened. But barring a crisis in the cold war, consumer prices generally are expected to hold steady through 1959.

Long-run Trends

Recent price history appears to reflect a built-in inflationary bias in the economy. Whereas in an earlier era the rising prices of a boom tended to be deflated in a recession, prices now seem to be only flexible upward. Persistence of this "ratchet" effect would lead inevitably to long-run inflation.

However, economic expansion is indispensable to full employment and the wage-price spiral that characterizes the inflationary process. Although this necessary condition is usually taken for granted in current proposals for the control of inflation, it is by no means assured. Some believe that industrial capacity has substantially caught up with postwar requirements and that the economy has lost its strong upward thrust. The factors essential to an expanding economy include: A growing population and rising rate of family formation; steadily increasing research and development of new products and improved technology; preservation of business incentives through a favorable governmental climate; expanding government services; labor mobility, as well as other things. If these conditions are not favorable, the danger is rather underemployment and instability than full employ, ment and rising prices.

In principle, long-run price stability is not incompatible with sustained economic growth. But because of uncertainty over the future, broad questions of national economic policy tend to be resolved in favor of full employment and production, rather than control of prices. Moreover, national programs, such as the farm price supports and tariffs, tend to place a floor under prices, with ceiling unlimited.

The Congressional Joint Economic Committee has been conducting an exhaustive analysis of the inflationary process and measures to control it. And the President recently established a Cabinet committee to study governmental and private policies affecting prices and economic growth. Among other measures, the President asked the Congress to amend the Employment Act of 1946 to make it clear the "Government intends to use all appropriate means to protect the buying power of the dollar."

Monetary and Fiscal Controls

As indicated above, inflationary pressures are rooted in an excess of purchasing power in the hands of the public over the availability of goods. Since the monetary and banking system plays a crucial role in expanding money demand, control of the money supply offers the most hopeful prospect for controlling an inflationary threat. This is one of the important functions of the Federal Reserve System. Through their control over member bank reserves used as a basis for business loans and investment, the federal reserve banks can restrict the expansion of bank credit. This control is accomplished through changes in legal reserve requirements and holdings of government securities, together with appropriate adjustments in bank rediscount rates.

Without firm monetary controls the task of controlling inflation would be hopeless. Yet the limitations of monetary policy have been painfully evident since the end of the war. Until 1951, the federal reserve banks subordinated their stabilization function to the support of the Treasury bond market. And since regaining independence from the Treasury their record has not been encouraging. This is partly because of the long lag between changes in the quantity of money and the time they take to become effective.

The federal reserve banks oppose the threat of inflation by restraints on the expansion of bank credit. This is generally accomplished by reducing their holdings of U. S. securities, thereby restricting member bank reserves, and by raising the rediscount rate, or the cost of member bank borrowing. Member bank reserve requirements may also be increased.

Delayed reactions, however, seriously limit the effectiveness of such "leaning against the wind." Uncertainties over business conditions delay the initiation of such moves; and it takes time to transmit these impulses throughout the system. Business generally is not responsive to small changes in interest cost and, moreover, is not entirely dependent on the commercial banking system for its capital needs. But the considerable elasticity in the use of money most seriously limits control over its supply. Between the end of 1954 and 1957, for example, the total amount of currency and bank deposits increased only 3 per cent: The increased volume of business was facilitated by steadily rising velocity in its circulation, outside the control of the monetary authorities.

The long-run stabilization objectives of the Federal Reserve System also tend to be thwarted by cyclical adjustments, in meeting the demands of Treasury financing, and by concessions to political pressures. Although the System attempts to limit the growth of bank deposits to the growth needs of the economy, excessive reserves may be created in meeting emergency requirements during a recession, thereby limiting control over future expansion.

To be effective, monetary policies need to be supported by appropriate Federal fiscal policies. This entails a counter-cyclical budgetary policy according to which inflationary excess purchasing power would be absorbed by a budgetary surplus. This was the situation between January 1955 and June 1957, when the Federal cash surplus was about $l3 billion. However, governmental budgetary policies are generally dictated by political and social considerations other than price stabilization. While Federal expenditures respond quickly to recession needs, they are less readily contracted during a business recovery. Also, higher taxes appropriate to a business boom are politically unpopular, and have yet to be enacted under peacetime inflationary conditions. Continuation of the sharp rise in Federal expenditures of recent years would appear to call for heavier Federal taxes, rather than tax reductions, if further inflation is to be averted.

Future Uncertainties

Inflation is a response of the price system to the operation of the economic "laws" of supply and demand. Unlike the physical laws of nature, these "laws" are economic tendencies whose control is limited principally by our knowledge of human behavior and predictability of the future. This large area of uncertainty has deterred the effective application of monetary and fiscal instruments of control already developed. By perfecting our knowledge of human behavior this uncertainty can be reduced, and the future can be better shaped by more rational plans and objectives, not simply awaited.

It is by no means agreed, however, that inflation is a clear and present danger, or more to be feared than its possible alternative of underemployment. Held to a creep, inflation is a small price to pay for full employment and economic growth if the risks of attaining price stability are too great. This is particularly true if real incomes continue to rise with economic growth and improved productivity. If this is the dilemma that confronts us, it is at least a happier prospect than the stagnation hypothesis that haunted the last generation, during the Great Depression.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"The Nasties Upset Since Bunker Hill"

February 1959 By COREY FORD '21h -

Feature

FeatureThat Other Dartmouth Carnival

February 1959 By FREDERICK L. BACON '59 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Dinner Honors Football Team

February 1959 -

Feature

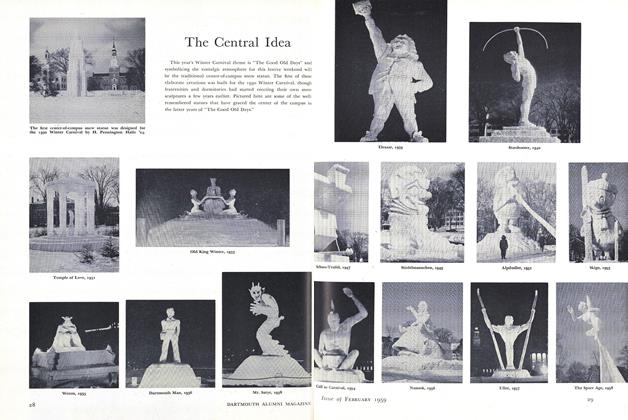

FeatureThe Central Idea

February 1959 -

Article

ArticleSome Consequences of Inflation Psychology

February 1959 By COLIN D. CAMPBELL, -

Article

ArticleShould We Blame the Unions?

February 1959 By MARTIN SEGAL