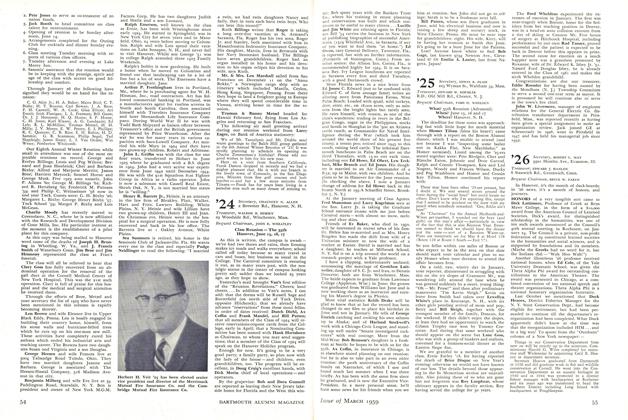

Flaunting established tradition seems to have been one of the hallmarks of genius through the ages, and so it is with Donald Cowlbeck '57 who has come up with an invention that may very well shake American suburbia to its split-level foundations. Cowlbeck is presently a student in the Graduate School of English at Princeton and within those hallowed halls and subdued surroundings he has more than once sought erudite meditation in company with that confrere of mystical delight, the carefully prepared martini. Like the generations of devoted martinilovers before him, he had always assumed that the ultimate martini, the perfect "it," could be achieved simply by painstaking attention to the proper brands of gin and vermouth, their proportions, and their serving temperature. For years it had been dogmatically preached by the faithful that all these factors plus a skillful blending of ingredients stirred in a clockwise (although some prefer counterclockwise) direction culminate in the apex of the martini-lover's art sometimes referred to by the irreverent as Martiniism —in mixing the finest palate-smoothing drink possible.

However, a latent heresy was about to come to life, for in the deep past Cowlbeck had once received advice from poet Robert Frost to always "think of ultimates and true essences." He began to analyze the true quintessence of that little bit of consummate wisdom that he had held in his hand so frequently and with so much affection; and Cowlbeck suddenly realized that into the midst of the most exacting martini mixture is introduced a tiny green stranger—the olive. "I decided," he says, "that to achieve the ultimate martini, one had to find, and preserve, the ultimate olive ovalesque, charcoal green with paisley flecks, and a constant five grams in weight."

Cowlbeck's attempt to preserve the ultimate olive from ultimate martini to ultimate martini has resulted in the "Olivett," an innocent enough looking object, which may, in time, take its place with the cotton gin, scotch tape, and frisbee, as a part of our cultural heritage. The "Olivett" is a black, spun-aluminum case shaped like an hour glass and about two inches in length. Inside the case is a long gold chain with an arrow on one end and a clip on the other. The olive is pierced firmly with the arrow, dropped delicately into the martini, and the clip is attached to the edge of the glass. It must be quickly stated here that not just any old olive should be pierced. This would destroy the real beauty and significance of the Olivett. Cowlbeck advises wisely that this is a decision second only to marriage, since a man is judged by the companion he keeps. Color, skin texture, and instinctive sense of conviviality are primary factors, but he warns that an eye should be kept to the years ahead, never making any definite commitment and always keeping in mind it's beautiful, but will it last? When the truly right olive is found, the lucky man is instructed to impale it on the Olivett's little golden arrow, and he is reminded that many cultures and ethnic groups precede this act with various ceremonial rites.

Cowlbeck claims that he has kept the same olive for three years. Its name is Gaston.

"I keep him in good gin," says Cowlbeck. "He looks better than a lot of people I know."

In view of the Olivett's potential contribution to civilization, Cowlbeck and his '57 classmate, Don Hutchins, who is also at Princeton, have agreed to manufacture the Olivett on a commercial scale, however, limiting their sales to that select group capable of standing in the vanguard of progress those still possessing $3 after income taxes.

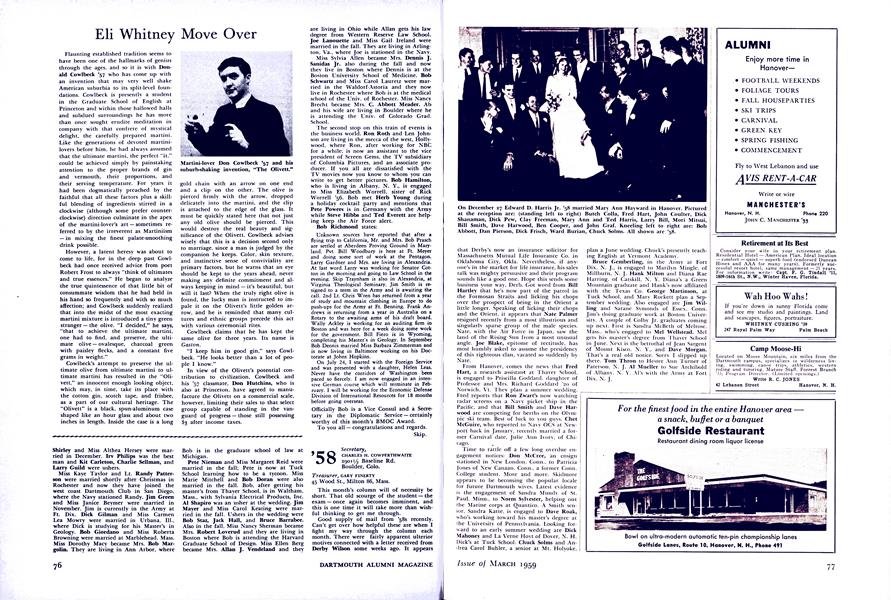

Martini-lover Don Cowlbeck '57 and his suburb-shaking invention, "The Olivett."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

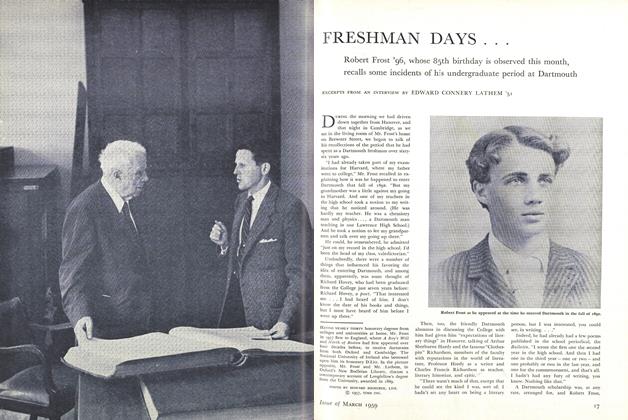

FeatureFRESHMAN DAYS...

March 1959 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

Feature"Spoiled Children" of Hanover: A Letter from Charles Doe, 1849

March 1959 By JOHN P. REID -

Feature

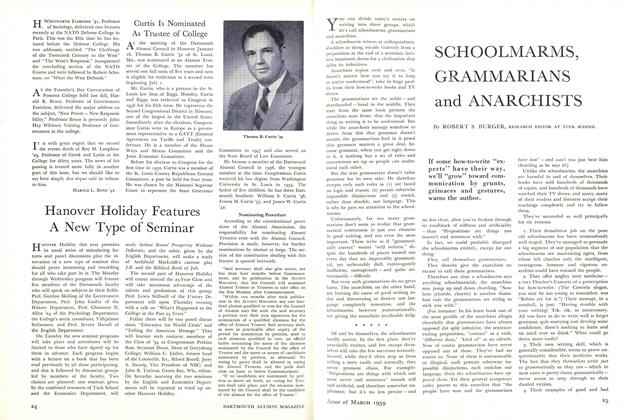

FeatureSCHOOLMARMS, GRAMMARIANS and ANARCHISTS

March 1959 By ROBERT S. BURGER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1959 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

March 1959 By SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

March 1959 By ROBERT L. MAY, EDWARD J. HANLON, BRUCE W. EAKEN