At just about the time this issue goes intothe mails, the Office of Admissions at Dartmouth will be sending out hundreds of letters to the boys who are successful candidatesfor the Class of 1964. The selection of theclass of 750 from 3700 completed applications was a long and arduous task, compounded of both tangibles and intangibles.The importance of the latter is the maintheme of Mr. Chamberlain's article, adaptedfrom a talk he gave at the joint meeting ofthe Board of Trustees and the Alumni Council in January.

'36, DIRECTOR OF ADMISSIONS

INDIVIDUAL alumni throughout the history of the College have obviously been the primary force through which undergraduates have sought out the College and entered its doors. Formal recruiting of candidates for admission began as early as the first meeting of this Council. And Sid Hayward reminded us, in his history of the Council which he wrote last year, that when Dr. Tucker wrote his first letter to the first Council he referred specifically to the sponsorship which the Council could give in attracting a student body of the highest quality. Through the Alumni Council, and in their behalf, the alumni have been interviewing candidates since the inception of the Selective Process in the early twenties, and this was the first known formalized effort by any college to use alumni in the selective process. I have no idea how many youngsters have been interviewed since the early twenties to the present. Annually, we are now interviewing some 3,000 candidates around the country, and between our alumni interviewing and enrollment processes we are employing the services and time and effort of thirteen or fourteen hundred different alumni.

The formal enrollment program was instituted about eight or nine years ago, largely through the pioneering and stimulating efforts of the Cliff Beans, the Don McKinlays, the John Faegres, the Lou Wilcoxes, and others of the Council, and is now under the direct leadership of John Willetts '40 as chairman of the Alumni Council Committee on Admission and Enrollment and as chairman of the National Enrollment Committee, which is a working arm of the Alumni Council.

We have in the past been tempted to talk about the nuts and bolts of admission: Scholastic Aptitude Test scores, average rank in class, number of boys from the top quarter, second quarter, top tenth, number from private schools and public schools around the country. And I venture to say that while these nuts and bolts are highly important in the operation of the admissions process, they are actually only the symbols of what we are after.

The paradoxical question is constantly being asked: Why do we have to seek out candidates when we have so many boys applying for admission? The answer to that, I think, is very simple; namely, that in any operation, whether it be in business or in a college, where we are dealing with a product, the product can be only as good as the raw material brought in. And if Dartmouth College represents to all of us what we think it ought to represent in the future, it can do so only if the raw material continues to improve. And another consideration is that the last ten or fifteen years have found our sister, and rival, institutions out on the road seeking the best possible talent. If we want to hold our own, we shall have to run very fast just to do so.

The simplest definition of the purpose of enrollment, and the purpose of admission, lies in President Dickey's statement to the incoming freshmen at Convocation every year: "You are the stuff of an institution, and what you are, it will be."

Now it seems to me that the job of enrollment is to find this "stuff," and the job of the Admissions Office is to select the best of this "stuff" from those who apply. This means, that the next question (after "What are we trying to do?") is a little more difficult to answer. That question is: What kind of stuff are we looking for? And this is the nub of the enrollment program, and the nub of the selective process, because if we could define through some magic formula the kind of "stuff" we are looking for, then those of you who are out looking for it would know what to seek and those of us who are selecting it would know how to select the class each year.

And before we can find any of these definitions of what we are looking for, we must step back and look at the College in perspective, because we must look for the kind of boy who represents the ultimate in the purpose of Dartmouth College. And until, or unless, we can understand the fundamental purpose, or purposes, of the private, residential liberal arts college, I venture to say we cannot find what we are looking for in our candidates.

Far better words than I could command have been spoken on the purpose of Dartmouth College, and on the purpose of a liberal arts college. I shall not attempt to do anything in that direction. I suspect that all of us here have a feeling for this purpose, even though none of us may be able to articulate it.

Before leaving purpose, I would like to suggest to you that there are forces chipping away at the traditional concept of the liberal arts college. Now, these forces might very well alter the total concept of the purpose of the College as we have understood it for a couple of hundred years; they could very well alter the purposes and practices and policies of an admissions office. Whether they should or not is not for me to say here, even though I have my own private opinions about them. But I think we must be alert to them because they are significant.

Some of these forces arise from the fact that we are in an era where there is a constant and early drive toward specialization - far more than we knew twentyfive years ago, and I'm sure far more than was known fifty or sixty years ago.

We are also in an era in which subjectoriented teaching is a rising factor. Subject-orientation has always been impor- tant in teaching. The teacher who is not interested in his subject wouldn't be a very good teacher. Thus, it's the subject itself that has always been the primary orientation, but I suspect that today subject-oriented teaching as opposed to human-oriented teaching is really more prominent and prevalent than it's ever been.

We're in an era of increasing importance of graduate school to the ultimate careers of these lads. We now send sixty to sixty-five per cent of every graduating class into graduate schools. The drive to get into graduate school is, therefore, much stronger, and in much larger numbers, than it was thirty or forty years ago; and in some senses I suppose you could consider that a college like Dartmouth is a preparatory school for graduate school. And even as preparatory schools feel the impact of college requirements for admissions on their programs, so does the college feel the impact of requirements for admission to graduate school on its program.

We are also in an era that makes a fetish of statistical measurement of everything possible about a human being. Unless we can reduce something to a coefficient of correlation and add it up and find that we've got a number higher than another number, or lower than another number, people are unhappy. This certainly is bearing in on any consideration of how boys are doing in college or what we do in the Admissions Office. I don't know where all this is going to take us, but we are in that era - the era of the IBM machines. This horrifies some of us because we don't know how they do what they do, and sometimes they really give out misinformation that is very "mis" once you get one tiny little hole in the wrong spot - as you all know.

We are also in an era of acceleration. The drive is to take kids just as fast as you can get them in secondary school, find out whether they've got special capacity in some areas, and then push them just as far and as fast as you can. I'm not saying this is bad. It may well be good. We are responding to it in our advanced placement program in the College and in our endeavor to place these boys in college at precisely the right level on the basis of their capacity and on the basis of their secondary school preparations - but this is a growing thing, this era of acceleration. How fast, or how far, you can accelerate with a lad who is trying to learn, I don't know, but we are in that era and we must take cognizance of it.

And then, as you of course know, we are in an era of atomic anxiety.

And I believe we are in an era of security before the risk.

I am now talking neither pro nor con about these pressures, but we must take cognizance of them if we are going to do the right job both in the College and in our admissions work. The Trustees Planning Committee Subcommittee on Admission and Financial Aid is considering many of these things in its study of the admissions and financial aid programs. This is a high-powered committee, a highly vocal committee, and a hard-working committee, with whom we've been meeting all fall and will continue to meet during the course of the year. They are digging into admissions philosophy and admissions practices from generalities down to the most finite details one can imagine. What their suggestions may be after the deliberations are completed I don't know, but these are some of the areas they are thinking about and some of the areas bearing in on admissions policy.

THERE are all kinds of people with special interests and special ideas about what should be brought to bear in the selection of a class. Personally, after having been in this business, more or less, for nearly twenty-five years, I think there are some fundamental things which will always have to be taken into account.

Obviously, since learning - if you will, "book larnin' " is really the primary business of the College (I think there are other things but this is the primary focus), obviously "book larnin'" and preparation to do "book larnin' " will have to take the primacy under any consideration.

But above that, I think the question of integrity is more important. Unless we can establish the fact that a boy has integrity, even though he may be the brightest guy in the United States, we have a real question as to whether he should be admitted to Dartmouth.

I think other allied areas are such things as decency - common decency - a sense of selflessness; not that the boy's got to be particularly devoted to the common weal, but at least that he is the kind of person who isn't going to knock everybody down in order to get to his goal.

These things such as integrity and common decency are things which I think will be universally important whatever else our selected classes will bring to this campus.

Then in the area of scholarship potential, which is fundamentally the core of what we're trying to get at (I can break this down into five or six categories each one of which can be measured to some extent and some of which cannot be entirely measured), I think first stands intellectual curiosity: If the fellow isn't hungry, he probably isn't going to go anywhere. Then there is intellectual capacity - he may have a lot of capacity, but if he doesn't have any curiosity that capacity is wasted.

Intellectual creativity is another facet. Does he have the drive to do something intellectually or is he just going to be a sieve through which somebody else's thoughts pass without being very useful to anybody including the learner? He must have some intellectual creativity.

He should have acadernic perseverance. Many a man is curious, many a man is bright, but when things get tough he just hasn't got what it takes to persist until he reaches his goal. This is an important consideration when making a selection.

And there is always academic preparation in specified subjects. This is important, but it may very well be the least important area here. A man who has had less than the best English preparation can sometimes forge through. He's better off if he's had it; he's better off if he's had foreign language; he's better off if he's had mathematics. Certainly, he should have adequate academic preparation, but there can be variances here which will not hurt the boy we seek.

And now, in no particular order of priority, there are additional areas which I think we must use, and which are important in our consideration of who gets in as between boys who are otherwise relatively equal candidates.

One of these, I would suggest, is the "special contribution" potential. This contribution might be a contribution to society. (Perhaps we have a super-specialist type of fellow who might invent an atomic bomb or have some way to keep the atomic bomb from being exploded, or we might have a boy of family background where it is inevitable that he must have, and will create, an impact on society whether he goes to Dartmouth or any place else.) This can be an important consideration.

Also there is always a question as to what special contribution to the College, to the student life of the College, in athletics, music, this sort of thing - or to the diversity of the student body - a particular boy may make. Just what is our "impact of youthful mind on youthful mind" if we don't have different kinds of people against which these minds can rub?

The whole question of alumni sons and their contributions to the College and the question of local relationships are always with us, and so it goes.

The trouble in trying to bring these things to bear in a simple definition of "what we are looking for" is that there is no pattern; the possible variables are so great as to defy even the IBM machine, and therefore we cannot come up to you and say, "This is what we're looking for."

Certainly, statistical measurement will have to be relied on, and probably will continue to be relied on, with ever-increasing emphasis, but there are far too many areas, gentlemen, in this business where statistical analysis will not do the job. We like to talk about statistics because they're there. It's easy to talk about numbers, but it's very difficult to talk about intangibles, and that's why we are so prone to discuss each class on the basis of statistics and grade averages and that sort of thing. But I suspect statistics do not really get at what we are trying to reach in our admissions and enrollment business. And, therefore, I suspect that even though we will continue to use statistics, in the long run - at least the next couple of decades - the subjective judgment, rather than the objective test, will be the weightiest method by which these young gentlemen are selected.

I am an advocate of the Gestalt theory that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. I believe that the whole boy is something different from the sum of any number of individual categories into which we can break him up; I believe that the whole entering class is something greater, and something different, from the sum of all the little segments into which we can break it up and analyze it; and I think that the whole College, and in fact the totality of the alumni body, is something greater than the sum of these various things which we can break into little parts and measure and talk about. And in this respect, therefore, I think that after adding up all the variables and measurable data, when we actually select a boy, even as I suspect you do when you select friends or when you select business associates or when you select kids in whom you are interested, we take a look at the folder, we find this number says this, that number says that, but we say in the net we think this boy is a better boy for Dartmouth College (to hell with the numbers) and we take that boy. Maybe we are wrong, but I suspect that this is what we really do. And I suspect we will continue to do it until, or unless, the statisticians come up with far better materials with which to work than we now have - good though they are.

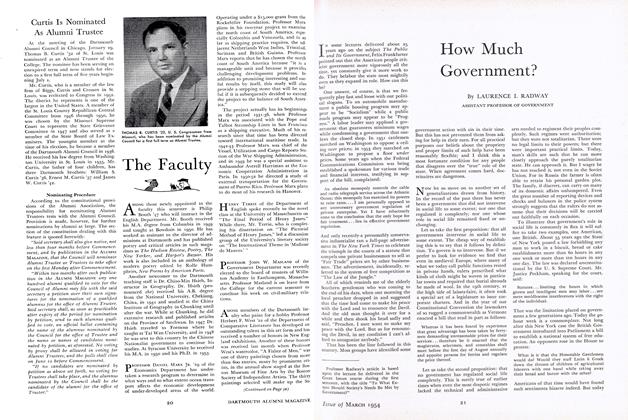

The director of admissions working his way through a stack of folders.

Hard at work in the Parkhurst "salt mines" last month were (seated, left to right) Frank A.Logan '52, assistant director, Charles F. Kettering '53, W. Hartwell Perry '55 and Davis Jackson '36, assistant director, all staff members of the Offices of Admissions and Financial Aid.Director Chamberlain stands behind them.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Poetry of History: William Faulkner's Image of the South

May 1960 By HENRY L. TERRIE JR., -

Feature

FeatureNATO in Trouble

May 1960 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31, -

Feature

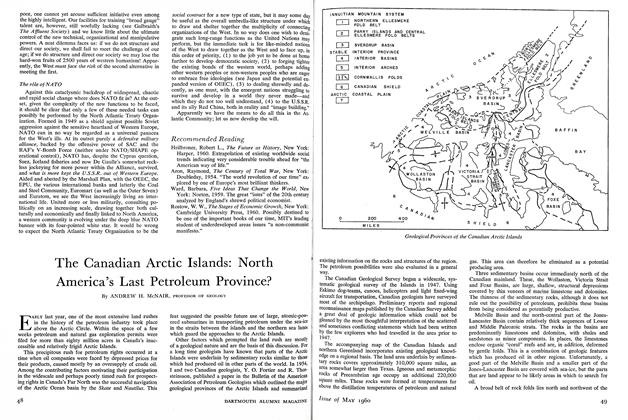

FeatureThe Canadian Arctic Islands: North America's Last Petroleum Province?

May 1960 By ANDREW H. McNAIR, -

Feature

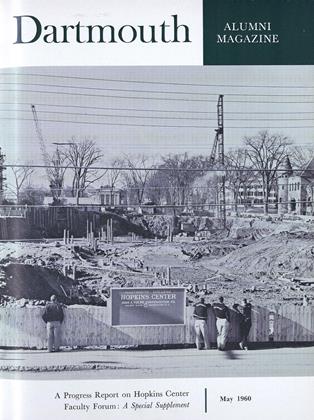

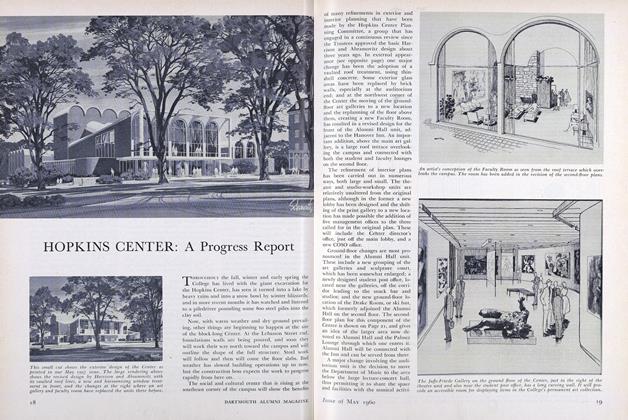

FeatureHOPKINS CENTER: A Progress Report

May 1960 -

Feature

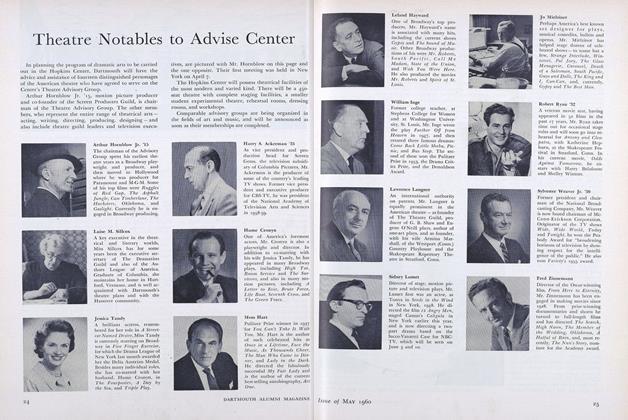

FeatureTheatre Notables to Advise Center

May 1960 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

May 1960 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, JOSHUA B. CLARK

EDWARD T. CHAMBERLAIN JR.

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1936*

January 1942 By EDWARD T. CHAMBERLAIN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936*

February 1942 By EDWARD T. CHAMBERLAIN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936*

March 1942 By EDWARD T. CHAMBERLAIN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936*

April 1942 By EDWARD T. CHAMBERLAIN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936*

November 1941 By EDWARD T. CHAMBERLAIN JR., JOHN E. MORRISON JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936*

May 1942 By EDWARD T. CHAMBERLAIN JR., ROBERT M.PRENTICE

Features

-

Feature

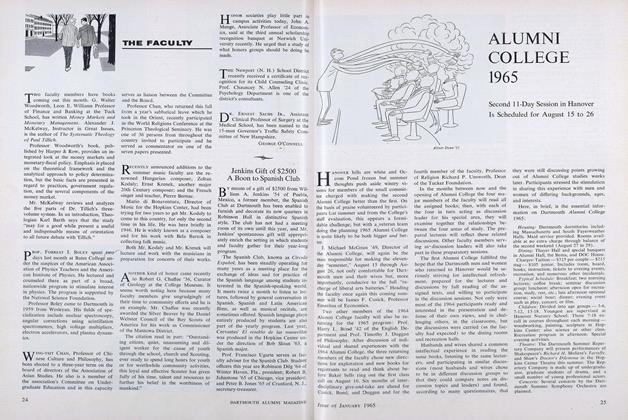

FeatureALUMNI COLLEGE 1965

JANUARY 1965 -

Feature

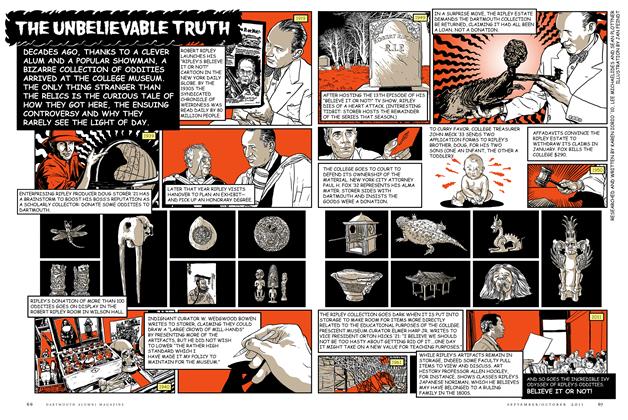

FeatureThe Unbelievable Truth

Sept/Oct 2011 -

Feature

FeatureTOM CORMEN

Nov - Dec -

Cover Story

Cover StorySUNDIAL

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureHow Much Government?

March 1954 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Feature

Feature"Our trusty and well-beloved John Wentworth Esq., Governor"

DECEMBER 1968 By Susan Liddicoat