THE 1960 CONVOCATION ADDRESS

We meet today in a setting and under a symbol which two weeks ago focused the attention of several thousand guests of the College gathering here for a public convocation on "The Great Issues of Conscience in Modern Medicine." The special symbol of that Convocation, with its four impinging areas, remains to remind us all that just as a physician stands answerable to patient, profession, society, and self, every highly educated man who presumes to minister to any part of the human plight faces, in one form or another, these omnipresent claimants for the attention of his conscience. These eighty-some flags overhead dramatize the reality, of our modern world, that these claimants speak to all of us in many tongues and that every man's knowledge must be a shared possession.

The fact of our bothering to gather together today as students and teachers in this historic ceremony marking the opening of the college year is itself a symbol of significance; it bears witness to each of us that "going to college" is a shared experience.

During the past two years I have addressed myself on this occasion to two aspects of this shared experience that enlarge and enrich our individual lives, whether Hanover Plain be our home for four or forty years. I besought then and I again bespeak a sharpened awareness on the part of each of us, whatever his station of duty, of that commitment of self which goes into making this place of higher learning the kind of community that is both a haven for the intellect and a hearthplace where in unique measure the warmth of the Dartmouth fellowship can be ours for enjoyment.

This fall's election will focus attention on the stake we all share in the larger community of the nation. It has been clear for some time that, regardless of which party wins, this election will mark the close in American public life of the postwar period. The span of man's life, the processes of change, and the circumstances of our time have combined to dictate that there shall now be a changing of the guard in both men and measures.

Other soothsayers will be telling us at some length and with great certainty who the new men are and what the new measures must be. I shall not venture far into that melee this morning. Rather I should like to offer for your continuing consideration a few observations on your relationship to this changing of the guard in our public life.

On this same occasion, 28 years ago, on September 22, 1932, President Ernest Martin Hopkins opened the college year with a prophetic address entitled "Change Is Opportunity." He faced an undergraduate body drawn from a country laid low by a complex of economic and social deficiencies which, for want of more adequate understanding, we called "the depression," a term as fearful in its way for the millions whose lives it blighted as was "the plague" for medieval man. Even though the American crisis of the thirties was essentially domestic, in contrast to today's international turmoil, I have not the slightest doubt that you are facing challenges of change in this country as well as abroad which have no precedent in human experience. Dr. Hopkins specified strength, in every human dimension, self-discipline, and leadership as the prime requirements for meeting the crisis and opportunities then facing the country and our youth. Despite all the spectacular scientific advances of the past quarter century, we do well not to fool ourselves about this - there is no miracle drug to take the place of that Spartan prescription for what ails us at such a time.

BETWEEN now and election day we will be hearing much about youth and leadership. Indeed reports of the part played by university students in recent political upheavals in Hungary, Korea, Japan, Cuba, and elsewhere have led many to wonder whether youth and leadership are not synonymous. As you know, the American undergraduate is sometimes compared unfavorably to his foreign counterpart just because he is not similarly storming the barricades of his existing order.

We need not waste energy on an argument that does no credit to either the courage of the foreign student or the judgment of his American counterpart, but if even idealism must have its chauvinistic testimonials, I am prepared to assert that such comparisons if taken seriously are slanderous in their misunderstanding and their underestimation of American youth. Such unfairness is bad enough, but what in my view is worse is the terribly mistaken picture of his place in today's world and of how he prepares for it that such incitements to contrived riot present to the American student.

It will do no harm, however, to say plainly that this view of the matter is not a back-handed plea for outlawing that native bumptiousness which is the biologic birthright of youth in every time and all lands. Education can properly be concerned with helping man to fly without committing itself to repealing the law of gravity. Likewise, I trust it is not necessary at this point for anyone who stands in the Dartmouth tradition of free intellectual inquiry to offer assurances that no new limit is proposed on that incitement to independent-mindedness by which all public-mindedness must be both created and judged.

No, on these matters Dartmouth stands where education has always stood: we're on the side of youth and also on the side of the wise counsel that "if we would guide by the light of reason, we must let our minds be bold." But it is no betrayal of American youth or of the liberal spirit to teach by word and example that leading by the light of reason in today's world is not child's play.

It would ill befit us in the comfort of our freedom and security to pass casual judgment on the raw courage and the sacrifices of life itself that thousands upon thousands of foreign youth have offered up to some cause of revolution in recent years. Whether within the pale of our approbation or not, they have been responding to the circumstances of their lot and more often than not the circumstances of their lot seemed to leave them no alternative except the primitive course of leading with their bodies rather than their reason. The least we owe them is to understand that.

I take it that this is what the French philosopher, Jean Paul Sartre, himself a leader of the intellectual left, meant when, in commenting on the Cuban revolution, he said: "Since a revolution was necessary, circumstances bade the children accomplish it. ..." In turn, Sartre tells us that life, even on the so-called far left, is not just one big revolution when he also observed that: "The greatest scandal of the Cuban revolution is not the expropriation of the planters but the accession to power of children...." The point here, I think, is that any revolution worth its cost must rather quickly go beyond the excitement of revolt and when it does it confronts man with his ancient need for leadership and the management of power.

But the point I would emphasize here is that America and American youth in particular face a very different task of leadership than that of revolting from an outworn past by throwing the rascals out, either with bullets or ballots. I suspect that in the perspective of history your task is vastly more difficult as well as vastly different, but as I have said, I prefer not to pass judgment on how difficult it is for someone else to die, whether of necessity or foolishly. It is enough here for us to attempt to be worthy of the task which is ours.

In all things where reason is to light the way we begin with an effort to know and understand the fact which, as Mr. Justice Holmes once put it, life offers us for our appointed task. As is usual in human affairs, there are more facts than we can ever entirely know and understand about our situation. But, as always, we can begin knowing.

Although there can rarely be agreement among us on the definition of our most pervasive problems and especially with respect to their place on the agenda of time, there are few among us who do not recognize that even we in this most fortunate America have some fast growing up to do: in our race relations, our educational aims and standards, our moral philosophy, our use of the democratic process and, perhaps above all, in our understanding of the government necessary for civilized existence on a planet where suddenly, in terms of time and space, everyone is in everybody else's backyard and, as we ought to expect, mostly damn unpleasant about it.

If you would get some feel of the first of those tasks consider the long, drawn-out deliberation and determination whereby this fall this campus is for the first time free of external racial and religious barriers to fraternity membership. And if you would know just a little of the difficulty that faces men who seek to have this enlightened land participate, let alone lead, in establishing a minimum measure of law over the conduct of nations, examine the hairbreadth margin whereby the House of Delegates of the American Bar Association only last month gave grudging endorsement to the effort of President Eisenhower and others to have this country now accept, without the reserved right of a national veto, the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice.

Reason alone can lead us to positive answers to such problems. Mobs, whether composed of students or savages, can only destroy and never create because they are a mechanism of hate rather than of mind. There are few things more fundamental to a man who aspires to the power of higher learning than an acquired distaste for mobs. Never doubt that this distaste requires our constant cultivation. This is especially true for the American student because it is his lot to inherit an appointed task of personal and national leadership that simply cannot be performed in hotheaded self-indulgence.

We all easily agree that this is the fact life offers America as her appointed task and, at least in between Presidential election campaigns, most of us, regardless of our political theology, rest rather comfortably on the assumption that we are responding to the tasks of leadership about as well as can be expected. At the tactical level I have no broadside of complaint as to the conduct of the cold war either at home or abroad. And I share with most of our countrymen the enormously important confidence that in the main America has both the right friends and the right enemies.

MY misgivings come when I ask myself whether in American society generally, or on either side of the aisle of political leadership, we are committed to aspirations for the international community that will generate and sustain the ideas from which alone comes the forward thrust essential for any great leadership. If there is room for real doubt about this - and I shall leave it for your own pondering - then in the long run all else is in doubt. It would be naive or insincere in the extreme to encourage undergraduates to believe that they are ready to take the world "to town" if only they could get a hand on the wheel and a foot on the accelerator of affairs. This is not the truth of things even though it is sometimes so represented by those who are more interested in using youth than in their education.

What is true is that you are now preparing yourself for the certain day when imperceptibly, or perchance suddenly, you will discover that the stick in your hand is not a club but instead the tiller of a human enterprise entrusted to your hand and heart. And if that enterprise should prove to be simply yourself and a fine mind, you will still know the challenge and the rewards of the leadership for which you now prepare.

Whether the enterprise in your case be a mind or a nation, and regardless of all else in the way of intellectual and moral preparation, you would also do well to begin now the unending task of cultivating a capacity for being undismayed because the dismayed are the faint of heart when heart is at issue. And never doubt it, leadership means being at issue with yourself as well as with your enemy. Above all, you will need that capacity for commitment of which we spoke last year because only out of commitment is any man fulfilled with his fellows, whether in the embrace of fellowship or loneliness of leadership.

The idea of leadership gets part of its vitality from the fact that it embodies within itself two opposite, alternating pulls of human experience. On the one hand the lessons of tyranny are deep within us and the democratic idea still walks warily in the presence of any leadership. On the other hand there are few more predictable social reactions than the way our society, in both its public and private sectors, cries out for leadership at times of crisis. I sometimes test the validity of this reaction by wondering whether, if we could imagine a society without deadlines, such a society would ever have had any need of the idea of leadership. I am brought back to earth from this speculation by realizing that the immortal society I was hypothesizing is in fact man's view of Heaven. Whatever our view of Heaven, we surely agree that one of the most conspicuous elements in the fact life offers us on earth today is a pervasive and continuing urgency in matters of public policy.

We cannot here enter into a discussion of what has sometimes seemed to be an unresolvable dilemma, namely, the reconciliation of democracy and leadership. It is my deep conviction that life on either horn of that dilemma is intolerable for our society and, indeed, was so regarded by the Founders when they gave us our republican form of government. The democratic idea is always under challenge — that is the inner nature of the creature and its good health depends upon it; but it is just when these challenges are most insistent and urgency is chronic that the democratic idea must look to its own leadership for its own survival. Its own best leadership is a democratic process infused at every level with men who follow because they could also lead - and vice versa.

The time permitted for solving a problem has always been one of the fundamental factors on any job. Whether the urgency be the brief sixty minutes permitted you to shine on the all-too-familiar "hour exam" or the fact that for nations war is a race to victory where the prize is survival, our mortal and finite world at every point is bounded by time factors.

I believe myself that today's central challenge to man's moral and political development is that the time factor permitted to him in the past for a gradual evolutionary growth has been suddenly and drastically cut short by the scientific revolution and the cascade of physical power it has loosened onto a socially and politically primitive international community. It is almost as if some change in man's physical environment suddenly threatened his biologic survival unless he should be able by the efforts of his own mind to short-cut the ageless evolutionary processes of change by quickly altering his genes to meet the new conditions of life. Man's built-in resistance to social change has undoubtedly in its way served man well, but can there be any doubt that it also and inevitably tends to make us impervious to even an awareness that the time factor in our public affairs has suddenly been cut to the point where man's most ancient reassurance, that "time cures all things," has become his most dangerous delusion?

And is it not certain that realistic awareness of this urgency and the will to meet it will come to us only as we can match awareness of our problem with a sense of having some answer for it? It is because I believe this to be so and because I do believe that leadership is man's only tried and trusted answer to great urgencies and that bold minds are his only hope for creative solutions, it is because I believe these things, that I believe in you and in the greatness of the fact life now offers us for our appointed task - your education at Dartmouth.

And now, men of Dartmouth, as I have said on this occasion before, as members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such. Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be. Third, your business here is learning and that is up to you. We'll be with you all the way, and Good Luck!

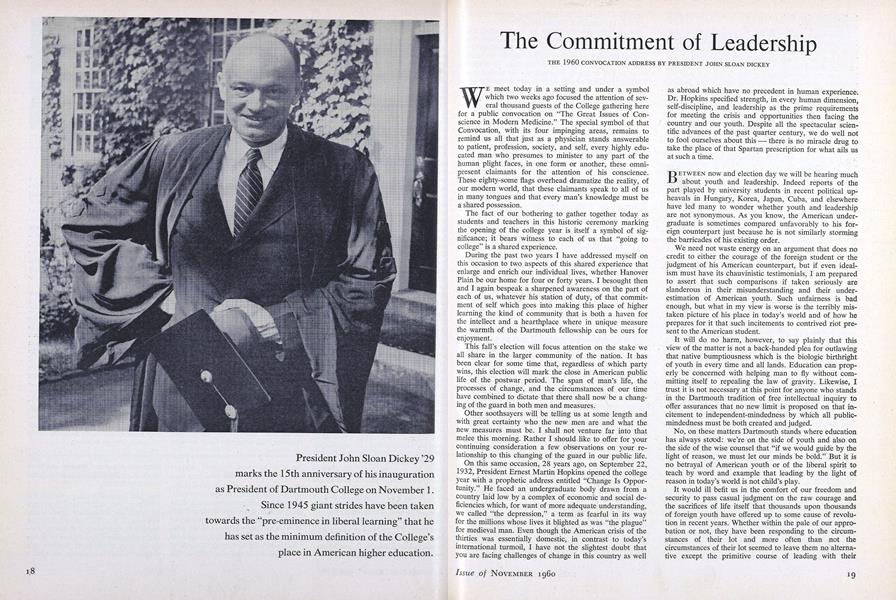

President John Sloan Dickey '29 marks the 15th anniversary of his inauguration as President of Dartmouth College on November 1. Since 1945 giant strides have been taken towards the "pre-eminence in liberal learning" that he has set as the minimum definition of the College's place in American higher education.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIt Was A Dartmouth Jinx All the Time

November 1960 By AMOS N. BLANDIN '18 -

Feature

FeatureA Fulbright Year in France

November 1960 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Feature

Feature"The Era of the Shrug"

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleEvening Assembly

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleSecond Panel Discussion

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleFirst Panel Discussion

November 1960

JOHN SLOAN DICKEY

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA BIG NIGHT AT THE WALDORF

March 1958 -

Feature

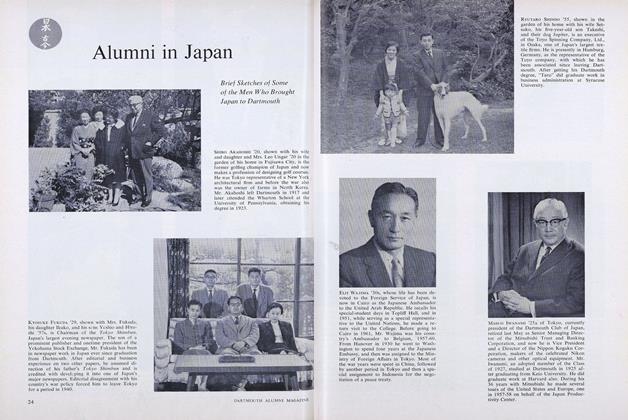

FeatureAlumni in Japan

MARCH 1965 -

Feature

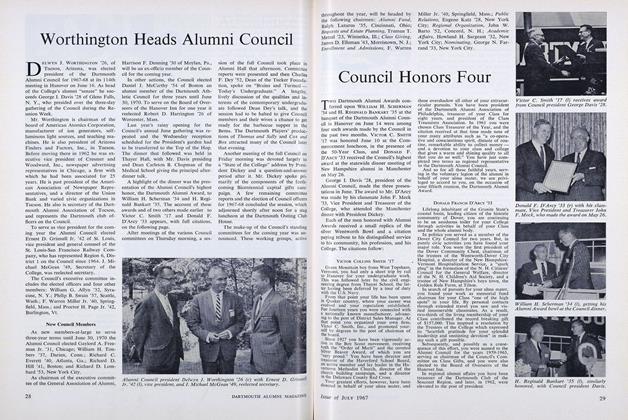

FeatureCouncil Honors Four

JULY 1967 -

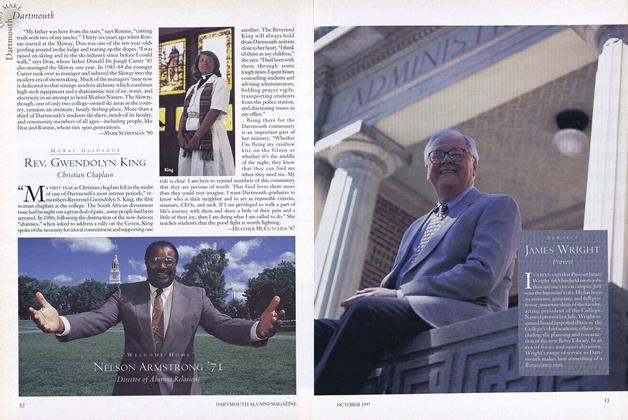

Cover Story

Cover StoryNelson Armstrong '71

OCTOBER 1997 -

FEATURES

FEATURESThe Natural

MARCH | APRIL 2022 By DAVID HOLAHAN -

Feature

FeatureLate Afternoon Thoughts On the Twentieth Century

September 1986 By LEWIS THOMAS