WE meet today in a setting and under a symbol which two weeks ago focused the attention of sev- eral thousand guests of the College gathering here for a public convocation on "The Great Issues of Con- science in Modern Medicine." The special symbol of that Convocation, with its four impinging areas, remains to remind us all that just as a physician stands answerable to patient, profession, society, and self, every highly edu- cated man who presumes to minister to any part of the human plight faces, in one form or another, these omni- present claimants for the attention of his conscience. These eighty-some flags overhead dramatize the reality, of our modern world, that these claimants speak to all of us in many tongues and that every man's knowledge must be a shared possession.

The fact of our bothering to gather together today as students and teachers in this historic ceremony marking the opening of the college year is itself a symbol of sig- nificance; it bears witness to each of us that "going to college" is a shared experience.

During the past two years I have addressed myself on this occasion to two aspects of this shared experience that enlarge and enrich our individual lives, whether Hanover Plain be our home for four or forty years. I besought then and I again bespeak a sharpened awareness on the part of each of us, whatever his station of duty, of that commit- ment of self which goes into making this place of higher learning the kind of community that is both a haven for the intellect and a hearthplace where in unique measure the warmth of the Dartmouth fellowship can be ours for enjoyment.

This fall's election will focus attention on the stake we all share in the larger community of the nation. It has been clear for some time that, regardless of which party wins, this election will mark the close in American public life of the postwar period. The span of man's life, the processes of change, and the circumstances of our time have combined to dictate that there shall now be a chang- ing of the guard in both men and measures.

Other soothsayers will be telling us at some length and with great certainty who the new men are and what the new measures must be. I shall not venture far into that melee this morning. Rather I should like to offer for your continuing consideration a few observations on your re- lationship to this changing of the guard in our public life.

On this same occasion, 28 years ago, on September 22, 1932, President Ernest Martin Hopkins opened the college year with a prophetic address entitled "Change Is Oppor- tunity." He faced an undergraduate body drawn from a country laid low by a complex of economic and social de- ficiencies which, for want of more adequate understanding, we called "the depression," a term as fearful in its way for the millions whose lives it blighted as was "the plague" for medieval man. Even though the American crisis of the thirties was essentially domestic, in contrast to today's international turmoil, I have not the slightest doubt that you are facing challenges of change in this country as well

THE 1960 CONVOCATION ADDRESS BY PRESIDENT

as abroad which have no precedent in human experience. Dr. Hopkins specified strength, in every human dimension, self-discipline, and leadership as the prime requirements for meeting the crisis and opportunities then facing the country and our youth. Despite all the spectacular scientific advances of the past quarter century, we do well not to fool ourselves about this - there is no miracle drug to take the place of that Spartan prescription for what ails us at such a time.

BETWEEN now and election day we will be hearing much about youth and leadership. Indeed reports of the part played by university students in recent political upheavals in Hungary, Korea, Japan, Cuba, and elsewhere have led many to wonder whether youth and leadership are not synonymous. As you know, the American undergraduate is sometimes compared unfavorably to his foreign counterpart just because he is not similarly storming the barricades of his existing order.

We need not waste energy on an argument that does no credit to either the courage of the foreign student or the judgment of his American counterpart, but if even idealism must have its chauvinistic testimonials, I am prepared to assert that such comparisons if taken seriously are slanderous in their misunderstanding and their underestimation of American youth. Such unfairness is bad enough, but what in my view is worse is the terribly mistaken picture of his place in today's world and of how he prepares for it that such incitements to contrived riot present to the American student.

It will do no harm, however, to say plainly that this view of the matter is not a back-handed plea for outlawing that native bumptiousness which is the biologic birthright of youth in every time and all lands. Education can properly be concerned with helping man to fly without committing itself to repealing the law of gravity. Likewise, I trust it is not necessary at this point for anyone who stands in the Dartmouth tradition of free intellectual inquiry to offer assurances that no new limit is proposed on that incitement to independent-mindedness by which all public-mindedness must be both created and judged.

No, on these matters Dartmouth stands where education has always stood: we're on the side of youth and also on the side of the wise counsel that "if we would guide by the light of reason, we must let our minds be bold." But it is no betrayal of American youth or of the liberal spirit to teach by word and example that leading by the light of reason in today's world is not child's play.

It would ill befit us in the comfort of our freedom and security to pass casual judgment on the raw courage and the sacrifices of life itself that thousands upon thousands of foreign youth have offered up to some cause of revolution in recent years. Whether within the pale of our approbation or not, they have been responding to the circumstances of their lot and more often than not the circumstances of their lot seemed to leave them no alternative except the primitive course of leading with their he found no method of controlling the thinking of the subject. The use of pillows - that whispered propaganda while subjects slept - was effective in the pages of Aldous Huxley's brilliantly imaginative book, Brave New World, but there's no evidence that I know of that a man who is unconscious from sleep or any other cause can be persuaded of anything, least of all of something he does not want to believe.

I shall not discuss hypnotism or subliminal suggestion by advertising. Neither procedure, I am told, has any long-lasting brain alteration.

In conclusion, it is fair to say that science provides no method of controlling the mind. Scientific work on the brain does not explain the mind - not yet. Neither the work of Pavlov on conditioned reflexes nor that of any other worker has proven the thesis of materialism. Surgeons can remove areas of brain, physicians can destroy or deaden it with drugs and produce unpredictable fantasies, but they cannot force it to do their bidding....

"Modern Medicine" as used in the title of this symposium means, I suppose, scientific medicine in contrast to older traditional practice. But do not forget that medicine is an art as well as a science, and unlike some other arts it has in it a religion of its own. The art and the religion are very old, older in fact than Christianity. There is goodness and compassion in every man. Sometimes it is well hidden, I admit, but in my experience it is always there. Here is the ancient source from which medical religion was drawn - the innate kindliness in man, himself. Here is the hope for the future of man, and evidence, too, if you like, of what the intent behind Creation may have been. Science is another matter. It has grown and changed from year to year, and therapy has known its fads and fancies, but the art of medicine with its own peculiar ethics has in it an eternal quality derived from life itself....

Dean Marsh Tenney said at the opening meeting of this symposium, "Science cannot be immoral and science cannot create morality." This is true, but philosophical and religious thought has been retarded by the general impression that

science had proven something in this sphere. Physician and scientist must make reasoned conclusions each for himself. Turning from science, to look at his own brief life, at his family, and at society as it is, like all other men, he would do well to turn back to man's ancient faith. Many a son sees misinterpretations in the religion of his father, but the Great Truths are there too. The brain of man today is no swifter than the brain of man when these truths were formulated.

Let us take, then, the best conclusions of the past and create a working religion, - a faith that will seem reasonable to all men, - one they will welcome. How? I do not know. The world has need of great religious leaders, men who like Gandhi will discard no good thing in the faith of Christian, Mohammedan or Hindu, men who will show us how to live by our beliefs. As Hippocrates turned from the practice of a profession to a code of ethics, so all men must turn from the rush of life to discover a reasonable faith. Only an interpretation of religion suited to these times can create in the hearts of men of every nation a better conscience. Make them see that they must love their fellow men everywhere or be destroyed. Only this, I say, can save this unbridled generation rushing on, confused, to self destruction.

Speaker: SANDOR RADO PROFESSOR OF PSYCHIATRY AND DEAN, THE NEW YORK SCHOOL OF PSYCHIATRY

TODAY, a fit of rage may terminate civilization. Rage is the enemy of civilized man. The Cave Man lived by the strength of his rage, his automatic resort to violence. Since contemporary society depends for its survival on peaceful though competitive cooperation, society must, through its institutions, tame rage, check the resort to violence, and expand fellow feeling by educating the individual's enlightened self-interest to embrace the general welfare.

Self-domestication of the human species has been going on for millennia. In this evolutionary process - from place to place and from period to period - many elements of the moral code underwent changes. But the necessity to curb rage and violence remained. The organism had to develop, and did develop, machinery for making the moral code effective. From our medical point of view, we call the components of this organic machinery the mechanisms of conscience. Let me indicate briefly what we - in adaptational psychodynamics have learned about conscience: how its executive mechanisms are seen to evolve in the child, how it works and how we may attempt to increase its effectiveness.

Adaptational psychodynamics is a young science; building upon Freud's fundamental discovery, its aim is to develop an introspectional branch of human biology. In this framework, conscience may be defined as an organization of self-restraining and facilitating mechanisms concerned with the regulation of human conduct. Its working, like other phases of central integration, evidences the organism's basic orientation towards repeating pleasurable experiences and avoiding painful ones. While remaining susceptible to social influences throughout the life span, conscience originates in the child's dependency relationship to his parents. At one point the child thinks, "If Ido this, mother will say..." From here on, through repeated anticipation of parental criticism, the child acquires the capacity for self-criticism. Repeated parental threats, fear of punishment, fear of losing the parents' loving care are the motives that enforce obedience. Rage in the child leads to defiance. The disobedient child is punished, but he soon finds out that he can be punished only if detected. Prompted by defiant rage he now seeks to conceal his wrongdoings.

The child's continued reliance on his experience, the discovery that he can escape punishment by avoiding being caught, halts his moral development at this stage. Further moral advance is initiated by his growing conviction that the Authority - God, parent - knows, sees and hears everything. This conviction gives rise to the fear of inescapable punishment, or briefly, the fear of conscience. This is the only true mechanism of self-restraint. It obviously may reflect the influence of religious instruction though its roots lie deeper. I have seen psychiatric patients who were brought up by agnostic parents and who literally had never heard of God; nonetheless, they had a strong fear of conscience. The omnipotence that the child attributes to his parents stems from his primordial illusion that he is omnipotent himself. He develops this fateful generalization when he gains control of his hands and feet. Forced by experience to delegate his limitless power to his parents, he of course expects them to use it for him; alas, they also use it against him. Belief in omnipotence is reinforced rather than created by religious instruction.

While the fear of detection has its effect, it may be too weak to restrain defiant rage, but fear of inescapable punish- ment can do it. What happens is this: when defeated, defiant rage automatically turns around and is then vented on the self. One may catch the child wildly beating his head with his fists. He later abandons his muscles and learns to belabor himself by means of self-critical thought. Retroflexed rage helps fear of conscience to repress defiant rage and to keep the temptation to reactivate it in check. The enemy - defiant rage - is thus conquered with the aid of its own deserter retroflexed rage. The vehemence of self-reproach and, as we shall presently see, of self-punishment is no direct reflection on the quality of parental reproach and punishment; it is a measure of the individual's own retroflexed rage.

However, even the fear of inescapable punishment may be defeated by the combined power of prohibited desire and defiant rage: the child transgresses - with compunction. His guilty fear of inescapable punishment, far from being an added restraining force, is but a signal that his security is endangered. It brings into play the reparative procedure of expiatory behavior taught him by his parents: he is reprimanded, must make a confession, take his punishment, promise never to do it again, and ask for forgiveness.

This pattern becomes the starting point of momentous developments. Through repeated anticipation it too becomes absorbed and automatized. Thus, parental reproach gives rise to self-reproach; parental punishment to self-punishment; parental forgiveness to self-forgiveness. In the course of time, this expiatory procedure can become completely automatic: the child, and later the adult, executes the pattern without having the remotest inkling of what he is doing. Even in the adult's mind, hidden from his awareness, his automatized expiation remains addressed to his parents. Hoping for forgiveness he punishes himself, but all that he (and others) are actually aware of is that somehow he has unintentionally done himself an injury.

Automatized expiation, while serving as a channel for the discharge of overflowing tension, defeats the purpose of healthy conscience; it belongs to the pathology of conscience. Voluntary repentance too becomes a menace if the repentant exalts the suffering he has inflicted upon himself into license to commit fresh offenses towards others. Such types have been described by Dostoevski, this finest literary expert in the pathology of conscience.

Under the pressure of retroflexed rage, many individuals develop guilty fear - from imagined guilt. They are then bound to torture themselves unendingly - for the benefit of no one. The more preoccupied an individual is with quieting his needlessly troubled conscience the less he has to offer to himself or to the community.

With its rage turned against itself the organism is safe from the danger of destroying others. But now it faces the danger of destroying itself - on the installment plan. One sees the consequences in every branch of clinical medicine. To allow retroflexed rage to dominate conscience is dangerous.

This takes us back to the problem of rage. At some future time, we may be able to reduce the strength of rage by some biochemical control, if not through modification of the human organism. At present, we are trying to do it by a psychotherapeutic procedure known in the terminology of the science of adaptational psychodynamics as "rage abortion."

The other crucial point is that guilty fear and the purely emotional repair work of expiation have little value in adult life. The rational response to one's wrongdoing is to apologize, pay damages, and be satisfied with learning one's lesson for good. Conscience need not be dominated by mechanisms of the stern punishment system under which the child is rarely if ever rewarded. We arrive at very different results by using the appreciative reward system, under which the child is rarely if ever punished. Thanks to the same processes of repetitive anticipation, parental reward creates in the child the automatic mechanisms of self-reward known as self-respect and moral pride. By shifting the emphasis from inhibition to facilitation, the reward system builds a healthy conscience: we give the child ideals, ingrain in him the value of integrity and courageous enterprise for their fulfillment. Under the reward system, we teach him to use his emotional resources for the intelligent pursuit of adaptive - i.e. realistic - goals. The guiding influence of intelligence and reasonable judgment on the emotions will make him more able to meet the responsibilities and seek out the opportunities he will be facing in life. It will help him to unfold in full whatever capacity he has for creative achievement. There is no substitute for self-reward: it is the emotional experience that makes man self-reliant. In the long run, if he succeeds in developing this pattern he is bound to win the recognition of his fellows.

The punishment system succeeds least with the self-willed child who needs help most. By provoking his enraged defiance, it tempts - if not prompts - him to do precisely the things which are prohibited. His only resource for conquering this temptation is to strengthen the inhibitory action of his guilty fear by automatically turning more of the torrent of his outward bound rage back against himself. But the next provocation gives added strength to his defiant rage, and with it to his temptation to transgress. The now necessary counter measure - reinforcement of his guilty fear by still more retroflexed rage - creates an ever mounting tension. The vicious circle is established. Observation shows the outcome: his capacity for productive performance will fall approximately at the same rate as his inner tension rises.

The reward system, instead of pinning the child's attention to things prohibited, lures him to constructive goals. Rather than increasing his fears, guilty fears, rages and retroflexed rages, it awakens and fosters his desire for reaching these goals. This way, it sets the stage for pleasurable activity and fulfillment. It teaches the child to experience moral pride and enjoy socially justified self-respect. He will thus be prepared for treating others with sincere consideration and respect. Though the reward system calls for lenience, it steers clear from indiscriminate "permissiveness." The latter attitude is anything but educational; it is usually resorted to by parents who are both frightened and misguided.

The here outlined propositions of adaptational psychodynamics derive from clinical observation. It would be desirable to test the validity of the whole conception on a larger scale by a special experiment in the upbringing and education of a group of children.

Rage is an open threat to the survival of the species. Retroflexed rage, by means of which traditionally organized - that is, punishment-centered - conscience operates, is an insidious threat to the health and life of the individual. In order to prevail against these threats, maximal research effort should be made towards reducing the strength of rage to manageable levels, and towards improving the traditional organization of conscience.

Sir Charles Snow: I was fascinated by Dr. Rado's exposition. I thought, almost from the beginning, that the title of this convocation would have been easier for some of us if moral nature had been substituted for conscience in the actual assignment. I agree that conscience, for me certainly, has this inhibitive meaning, and I think for most persons who are interested in people in the literary sense. And as Dr. Rado was talking, I had one question to ask him, because to me it's obvious that what he would like to do, and we would all like to see done, is going to be very much more difficult with some people than with others. This is not a thing where people start alike. And this seems to me to be one of my few quarrels with this kind of approach: it seems to be based upon romantic statistical optimism, so to speak.

I was thinking of the example he gave of the great expert on the pathology of conscience, Dostoevski, on which we should all agree. And then I was thinking of the two other experts on the pathology of conscience, Kafka and Kierkegaard. The three are not very similar but they have elements in them that are similar; they're all very marked examples of the inhibited functions. But I would have thought that there was a profound innate difference. Dostoevski, to his great good fortune, happened to be a man of very strong sexual temperament, which saved him from the worst inhibitive effects of his conscience and gave him the possibilities of selfreward. The other two, it seems to me, haven't got that great good fortune to have an abounding sexual temperament, which even Dostoevski had to fight his way towards. They, unfortunately, appear to have been made sexually impotent by the inhibitive effects of their conscience, and never got beyond the narrow streamlined reflection of what the inhibitive conscience really means. It seems to me you'll find that kind of contrast through a whole variety of the best of the population. You're going to find people will take - in Dr. Rado's language - to self-reward and be valuable to us in developing moral pride and all these things which we're exhibiting so triumphantly and suggesting for the future of the human race. But you're going to find people with whom it's much more difficult, and I would like to know if Dr. Rado has any feeling for the possibilities of the statistics? About how many people can you really do something with and how many you can't?

Dr. Rado: I'm afraid Sir Charles got me on our weak point of statistics. A practicing psychiatrist can talk only about his clinical observations and he calls them, euphemistically, "clinical impressions." Between "clinical impressions" on the one hand and statistics on the other hand there is a huge gap. Relying on my clinical impressions (live impressions), my feeling is that mistakes of traditional education, instead of bringing out the best that is available in these people, drives some of them into doing the wrong things. Because prohibitive education often defeats its purpose, because the inhibition tends to facilitate the opposite, it leads to transgression. That's the main point.

Now, how many people are capable of improvement? This amounts to asking what is the general level of intelligence ... and to what extent can the level of intelligence be raised? I have talked a good deal in Europe with peasants, simple farmers, and was often amazed by their intellectual resources. It is true these resources are usually underdeveloped, but I am sure education would do a great deal more for these people. In consequence the general level of decency would also rise.

Mr. Huxley: May I bring out a point here as to what is happening in the problem of rage and frustration. I think we have a lot to learn from the way the Greeks treated the irrational side in man. Many other societies, of course, have found the same way of coping with rage and frustration, which is not merely to have psychotherapeutic methods of dealing with it but total physical and muscular methods. For example, I went to Brazil. There unfortunate Negroes in the slums of Baia and Rio work off the rage and frustration of a perfectly intolerable life in these night-long weekly dances. It was very interesting to see; when one watched them, one could see exactly the same movements which were described in Greek Minoanism, the tossing of the head and so on, and one can see that this psycho-physical method - physical in relation to some kind of religious notion - is of the utmost importance.

It has always struck me that in modern psychiatry there is a terrible lack of dealing with the body as a whole. I mean, Freud tended to disregard the body, except as the two ends of the digestive tube - there was just the mouth and the anus - and nothing else! After all, there is something in between! And unless we cope with this and know what to do with it, I think we shall remain extremely impotent in the question of taming rage and frustration. And I think, as I say, there is a great deal to be learned from the Greek experience in this field.

Dr. Rado: I am advising people to keep a punching bag in the bath room and ladies a rag doll for the same purpose. What I want to say about Mr. Huxley's reference to Freud is this: I don't want any misunderstanding. This type of work I was reporting on is based altogether on Freud's fundamental discoveries but departs from his parables, from his metaphysics, and from his substitution of mythology for science.

Dr. Chisholm: Mr. Chairman, may I pick up a reference you made to the necessity for creative thought and imagination. I have the impression, and it's not more than an impression, that much of imagination which should be healthy and active has in fact been crippled by a too rigid internalized conscience control in childhood when the child got the im- pression from rigid parents, or relatively rigid parents, that to think in particular ways is good, to think in other ways is bad. And this becomes confused with the morality which in all our cultures is applied and must be applied to behavior. But many children confuse thinking with behavior, and can also apply the moral terms to thinking, which I believe should be confined to control of behavior, because if thinking can be bad, then imagination inevitably, I believe, is crippled, because there will be areas into which the child thinking is not allowed to adventure. This can carry on all through one's life. So that we find very large numbers of physically adult people who have closed areas in their minds which are not open or available for exploration; whole areas of human experience that are taboo from the point of view of their thinking. They're not allowed, by themselves, to think in these areas, because these were areas in which behavior was discouraged often by punishment when they were children.

I am very glad that Dr. Rado made a clear distinction between the reward system rather than a punishment system and the permissiveness which many psychologists are accused of upholding but which one finds very rarely upheld by any psychologist or psychiatrist - that is, an entirely permissive system.

I would believe that this question of the crippled imagination is one of the most important psychological questions that is facing the health professions now. And until we can loosen up our imaginations, we cannot use them for the full purpose and to the full extent of their potentiality. Imagination has some extremely important functions not fully used by most people yet. That is the exploration function.

Dr. Weaver: I had rather hoped that this would be introduced by one of my youngers and betters, but since no one else has, I'm going to mention what is obviously a controversial topic, but one which I think we all ought to think about. We have been discussing different ways in which the mind is affected and I think we should think for just a moment of the possibility of direct influence of mind on mind. I am in fact referring to that embarrassing, partially disreputable but nevertheless challenging body of phenomena known as "extrasensory perception."

I would like to mention the fact that I find this whole field intellectually a very painful one. And I find it painful essentially for the following reasons: I cannot reject the evidence and I cannot accept the conclusions. And I really don't know what anybody brought up in the scientific traditions does in those circumstances. A good many of my friends get around this difficulty by refusing to think about this topic at all. This is a kind of retreat and perhaps it is the only tolerable kind of retreat.

I cannot accept the conclusions of extrasensory perception because I simply cannot believe a body of phenomena that seems to fall so totally outside the classical framework of scientific procedure and scientific concept. I can't accept something that so totally overthrows all of the space-time order on which all of the rest of our science is based. I can't accept something that insults the whole notion of order of time, in which not only effect precedes cause, but knowledge of the event precedes the event. I cannot accept it. But on the other hand, I do not find it possible to reject the evidence.... I am absolutely convinced that there is something there; what there is there I do not know, and I must say that it worries me very deeply.

Dr. Gerard: May I suggest the answer to you? Accepting the statistics and accepting the incompatibility of the conclusion with practically all of our modern physical science, positives of science, my suggestion is that these few people for whom it has proven statistically valid have additional sensory modalities. Some few human eyes have been shown to have extraordinary perceptual capacity. There are other ways of looking at this than throwing out the baby or keeping the bath.

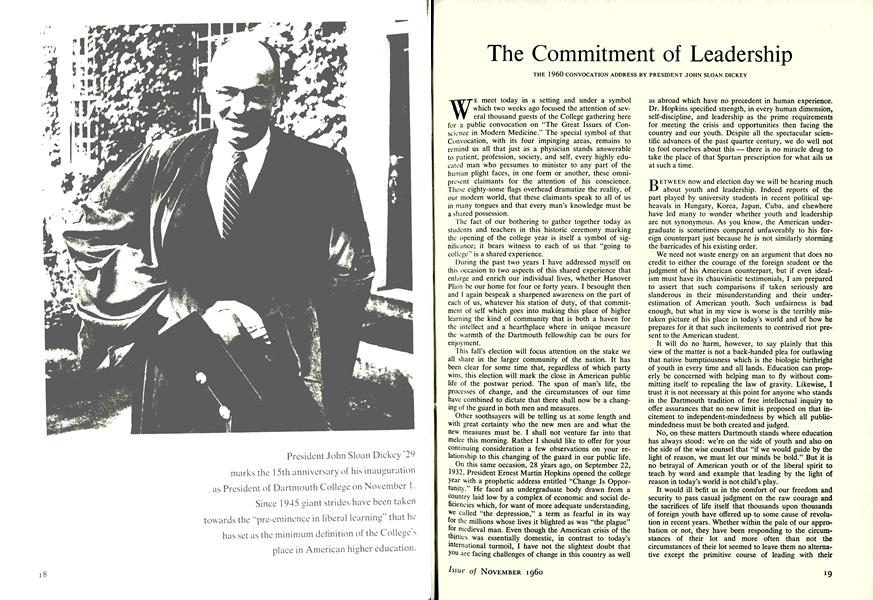

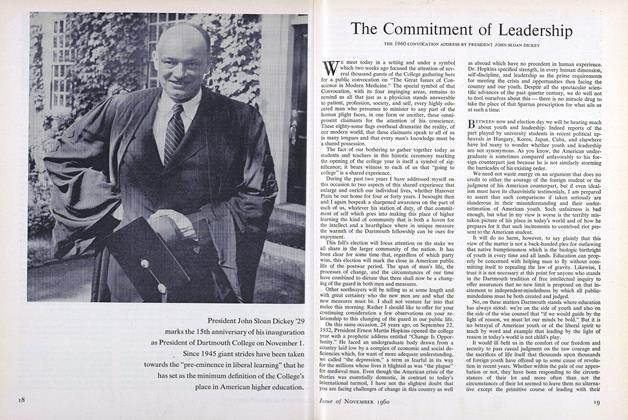

President John Sloan Dickey '29 marks the 15th anniversary of his inauguration as President of Dartmouth College on November 1. Since 1945 giant strides have been taken towards the "pre-eminence in liberal learning" that he has set as the minimum definition of the College s place in American higher education.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIt Was A Dartmouth Jinx All the Time

November 1960 By AMOS N. BLANDIN '18 -

Feature

FeatureA Fulbright Year in France

November 1960 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Leadership

November 1960 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

Feature"The Era of the Shrug"

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleEvening Assembly

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleSecond Panel Discussion

November 1960