To about two generations of living Dartmouth alumni the ghost of compulsory chapel still remains a weary memory.

The tradition, if it may be called one, started with the dedication of Rollins Chapel during the Commencement of 1885. The new Chapel provided ample room to house the entire student body, and it was enlarged several times later - thus lengthening its unattractiveness.

To many, this structure with its pink Lebanon granite and trimmings of Longmeadow sandstone has exemplified dreariness, duress, soporific virtue, and opaque sabbatism. Today, with its interior mollified by subtle pastels, decorative lighting arrangements, less strait-laced pews, and portals that open at will, it has lost much of its dingy and oppressive atmosphere.

President Tucker looked upon the chapel service as his principal opportunity to fulfill his responsibilities as the moral leader of the College. Although the daily morning exercises were brief and conventional, they did offer the occasion for bringing the College into unison, infusing into the undergraduates a feeling of solidarity.

Voluntary coherence not. being a natural attribute of the student body, attendance had to be checked, and rules set up to insure a reasonable observance of the daily chapel routine. As the student body grew in size an orderly means was instituted to record those present. A system of cards was introduced. These were imprinted with the date, and there was a line for the signature of the student, to be written in on the day of his attendance.

To Registrar Howard (Skeets) Tibbetts fell the onerous duty of checking these attendance tickets against the roster of the College, so that at the end of each semester he could report those who had failed to appear the requisite number of times.

In 1901 the Faculty Regulations read that "a student may absent himself from seven chapel services" per semester.. In 1917 the requirement was made more positive, but less onerous, with the rule that 65 appearances should be made each semester, with no excuses except to those students who were required to work at eating clubs during the chapel hour. By 1923 this had been reduced to 42 sessions. (Many thought that this was still too many.)

At first, for each excess absence, a deduction of one point was made from the student's general average. When this fell below 50 he was required to take additional work, the amount to be determined by the Committee on Administration. In 1917, with the attendance less restrictive, the penalty for poor turnouts was the deduction of one point and one hour credit for each three overcuts.

To the atheist, the late sleeper, the non-conformist, such a regimen was unpalatable, but the Faculty and Trustees were obdurate until June of 1925, when it was announced that starting that fall chapel attendance would be optional. What a heavenly word - optional. It became the synonym of rarely, scarcely, seldom, not often, and not-at-all.

The heralding of the chapel exercise each morning was by an elaborate ceremony of the Rollins bells, which had been donated by William E. Barrett of the Class of 1880 in the year 1903. These comprised a three-bell peal, and the bell of the lowest pitch could also be tolled.

Three college building custodians had the assignment of pulling the bell ropes. These were at a twelve-foot level in the Rollins tower, and were reached by means of an iron ladder and a trap-door. At 8:54 a.m. bell-ringer number one started pealing the highest pitched bell in a somewhat rollicking cadence. At 8:56 he was joined by compatriot number two, and at 8:58 by the third jangler. About thirty seconds before the stroke of eight o'clock this tintinnabulation suddenly ceased, and bell number three started to toll twenty times. This had the same effect as the "eight count" of a boxing referee, and immediately reduced the number of potential worshippers to those either inside the edifice, or those within about a 200-yard radius - provided they were fleet of foot and long of breath. If you were in front of the Bookstore or just emerging from College Hall you didn't have a chance. But if you had started across the diagonal duckboards, you might make it.

As the last doleful toll sounded, the chapel monitors slammed the three front doors in your face, and your humble entreaties and vigorous poundings were unheard through the two-inch-thick oak and iron-bound portals.

There were many ruses attempted by potential overcutters. Your roommate might try to hand in two cards on his way out. But these were usually detected by their dual thickness. You might bribe a "brother" who had already fulfilled his total obligation earlier in the year to attend for you and forge your name. This crime had to await detection in Tibbetts' Parkhurst basement. Or you might show up a few seconds after the end of the service and say that you had forgotten to pick up a card from the seat - and could you have one now?

Statistics are not readily available to indicate the relationship between overcuts at chapel and separations from the College. But there must be quite a few non-graduates who squirm a bit when asked, "And why did you leave Dartmouth?" To that will come the candid answer, uttered with bowed but irreverent head, and in distressingly mournful tones, "I went to morning chapel once too few."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Very Old and the Old

February 1962 By DR. FREDERIC P. LORD '98 -

Feature

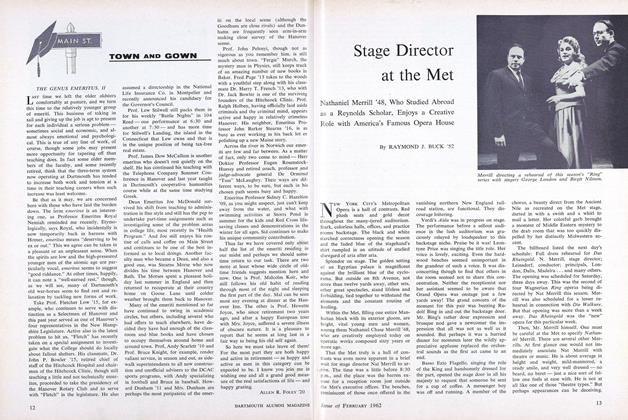

FeatureStage Director at the Met

February 1962 By RAYMOND J. BUCK '52 -

Feature

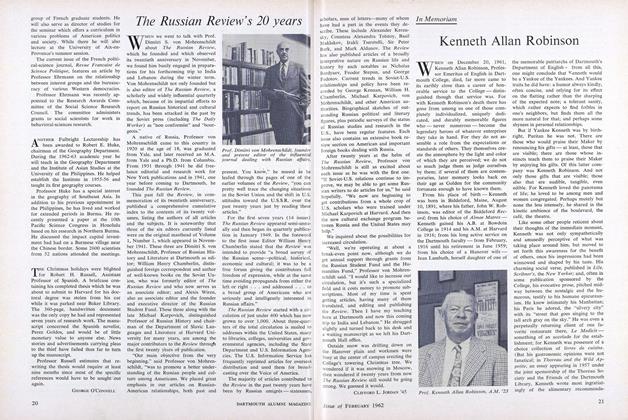

FeatureKenneth Allan Robinson

February 1962 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT -

Feature

FeatureELEAZAR WHEELOCKS, IN DIRECT LINE, STILL LIVE – IN TEXAS

February 1962 By SEYMOUR E. WHEELOCK '40 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

February 1962 By SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

February 1962 By WILLARD C. WOLFF, JOHN K. BENSON, JAMES B. GODFREY

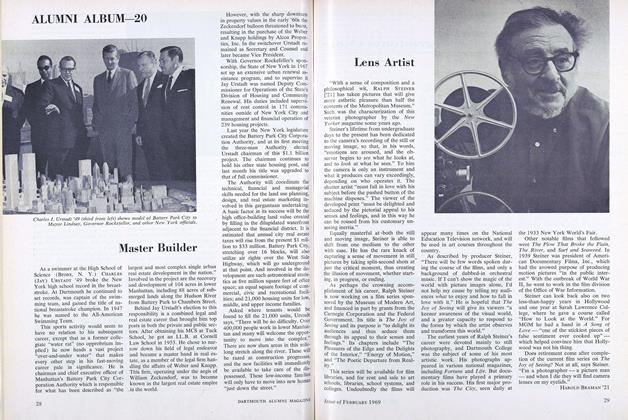

HAROLD BRAMAN '21

-

Feature

FeatureHORNING: Invention of the Devil

DECEMBER 1963 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Article

ArticleAle Man

JANUARY 1969 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Article

ArticleLens Artist

FEBRUARY 1969 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Article

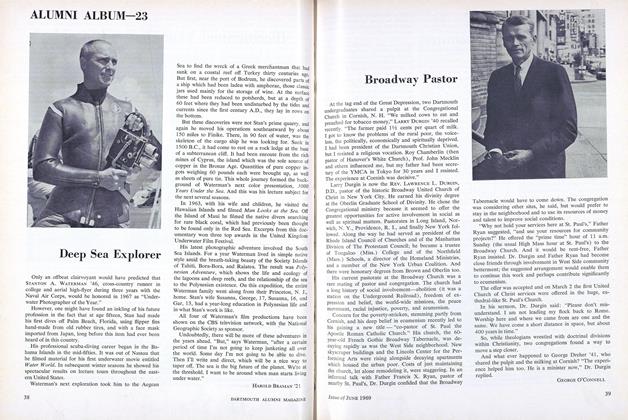

ArticleDeep Sea Explorer

JUNE 1969 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Article

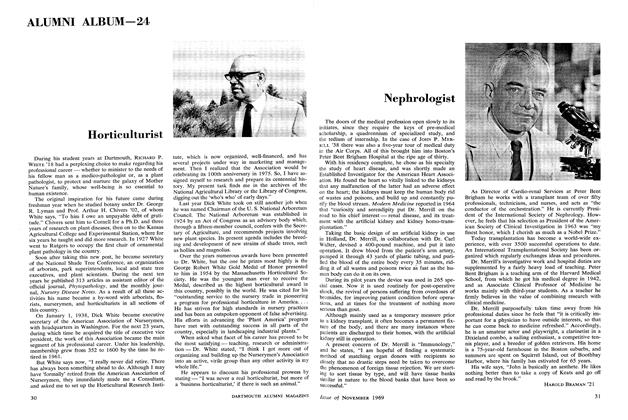

ArticleNephrologist

NOVEMBER 1969 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

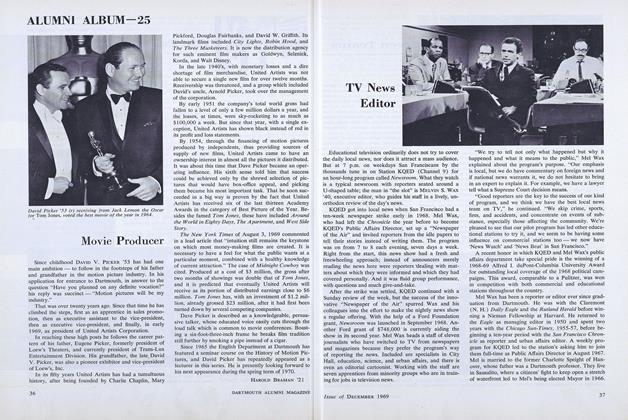

FeatureMovie Producer

DECEMBER 1969 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21