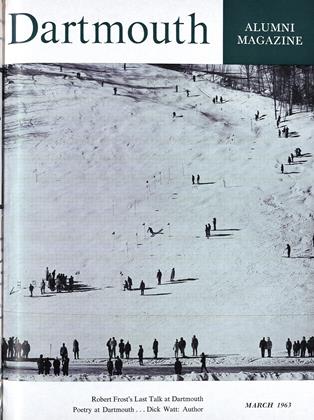

WINTER at Dartmouth is like a ring with one huge glittering stone at its center; and that stone is Carnival. During the first part of the term, a tremendous amount of energy is directed towards that center, and once it has been attained, a great deal of the energy expended in the second half is derived directly or indirectly from it; so that Carnival is thus the focus of the entire winter - its ne plus ultra and point of reference both before and after the fact.

This year, as usual, Carnival arrived almost before everyone was ready for it; and the week just preceding it was typically fast and furious, full of last-minute plans formulated in a day and either brought to fruition or abandoned overnight. The center-of-campus statue, for example, was barely finished on time, due to a spectacular lack of cooperation in building it on the part of fraternities and dormitories — a fact deplored extensively in the Daily D, and doubtless, in the Winter Carnival Council offices too. And as might be imagined, mail deliveries took on a special importance during those last few days, as was evident at the Hinman Post Office in Hopkins Center from the mingled eagerness and dread with which students fretted over the combination locks on their postal slots — too preoccupied, indeed, to notice or to care that they were no longer receiving those crucial letters at their dorms.

But shortness of time was by no means the only problem, for Carnival this year was ushered in by a cold spell so intense that it bade fair to stop the weekend dead in its tracks before it had really started. Friday as a whole, to be frank, was one of those all but completely unbearable winter days on the Hanover Plain. The mercury plummeted wildly, the wind was savage and merciless, and as a result, a simple walk out of doors became a struggle against implacable odds, an elementary effort to survive in which the ears were set singing until frost nipped them into silence, eyes were watered and blinded by the force of the harsh and astringent air, and hands and feet became stiff and unresponsive and weighted like lead. Fortunately, though, the cold broke during the night, and Saturday was mild and still and sunny - perfect Carnival weather; and the weekend settled, or rather snuggled, down into its old tried and true pattern of sparkling snow, flashing skis, flowing refreshments, pretty girls, and bad music.

To say that the music was bad is only to say that it was mostly rock 'n roll, which is still de rigeur at every fraternity party or dorm festivity and thus continues to hold the College, as far as its social functioning is concerned, under its unenchanting and inescapable spell. All weekend long the noise reverberated from the granite hills of New Hampshire. At the various houses there were the live bands, imported from Boston, with their electric guitars amplified to the point where they induced stupor, and their indistinguishable renditions of indistinguishable songs; and elsewhere there was the eternal drone of the phonograph, grinding out the agonizing endeavors of such succubi as Fabian and Ray Charles. The dance of the moment was of course the Twist, in approximately as many manifestations as Vishnu had avatars. But however audacious the modifications introduced - and some of the more extreme avoided the near side of masochism by mere inches - the basic step always remained: that same curious colloidal dispersion, with the partners circulating freely around each other in sort of formalized Brownian movement, churning and flailing enthusiastically, but like the blades of a rotary egg beater, never touching, and stirring up at best only froth and exhaustion - the twin results of so much modern entertainment. The Twist, far from being the most libidinous dance form ever evolved, is an outstanding example of a civilization that, at the crossroads of satiety and frivolity, refuses to take one path or the other and instead straddles both.

Elsewhere on the campus, however, the music was on a higher, not to mention less audible, plane. The Players were presenting The Threepenny Opera nightly on the main stage of Hopkins Center - at first glance a rather unusual show to produce for Carnival, considering that the offerings of the previous two years were The Pajama Game and L'il Abner. But the classic Brecht-Weill collaboration was given a superb mounting, with good singing, lively direction, and colorful and ingenious sets, costumes, and lighting. All possible objections vanished into air as Hanover audiences reveled in the pungent tang of Brecht's satiric tale of London low-life in the days just preceding Queen Victoria's coronation - only the low-life turned out to be quite contemporary in tone and outlook, and the city it inhabited more like Berlin in the 1920's than London in the 1830's.

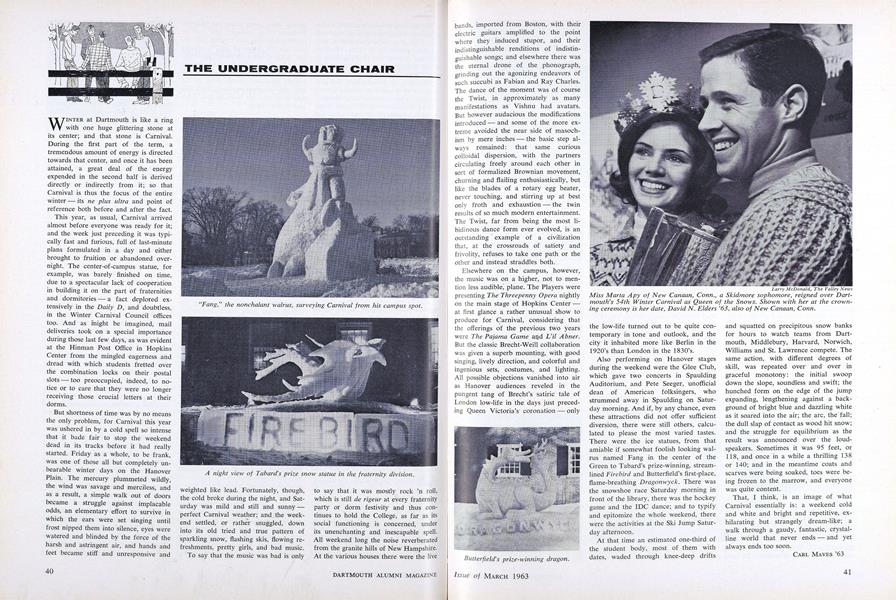

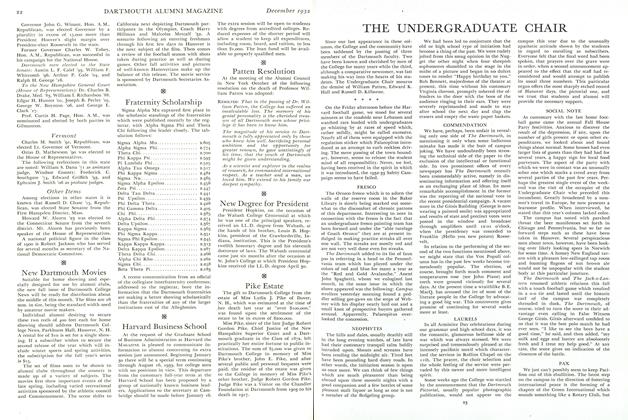

Also performing on Hanover stages during the weekend were the Glee Club, which gave two concerts in Spaulding Auditorium, and Pete Seeger, unofficial dean of American folksingers, who strummed away in Spaulding on Saturday morning. And if, by any chance, even these attractions did not offer sufficient diversion, there were still others, calculated to please the most varied tastes. There were the ice statues, from that amiable if somewhat foolish looking walrus named Fang in the center of the Green to Tabard's prize-winning, stream-flame-breathing Dragonwyck. There was the snowshoe race Saturday morning in front of the library, there was the hockey game and the IDC dance; and to typify and epitomize the whole weekend, there were the activities at the Ski Jump Saturday afternoon.

At that time an estimated one-third of the student body, most of them with dates, waded through knee-deep drifts and squatted on precipitous snow banks for hours to watch teams from Dartmouth, Middlebury, Harvard, Norwich, Williams and St. Lawrence compete. The same action, with different degrees of skill, was repeated over and over in graceful monotony: the initial swoop down the slope, soundless and swift; the hunched form on the edge of the jump expanding, lengthening against a background of bright blue and dazzling white as it soared into the air; the arc, the'fall; the dull slap of contact as wood hit snow; and the struggle for equilibrium as the result was announced over the loudspeakers. Sometimes it was 95 feet, or 118, and once in a while a thrilling 138 or 140; and in the meantime coats and scarves were being soaked, toes were being frozen to the marrow, and everyone was quite content.

That, I think, is an image of what Carnival essentially is: a weekend cold and white and bright and repetitive, exhilarating but strangely dream-like; a walk through a gaudy, fantastic, crystalline world that never ends - and yet always ends too soon.

"Fang," the nonchalant walrus, surveying Carnival from his campus spot.

A night view of Tabard's prize snow statue in the fraternity division.

Butterfield's prize-winning dragon.

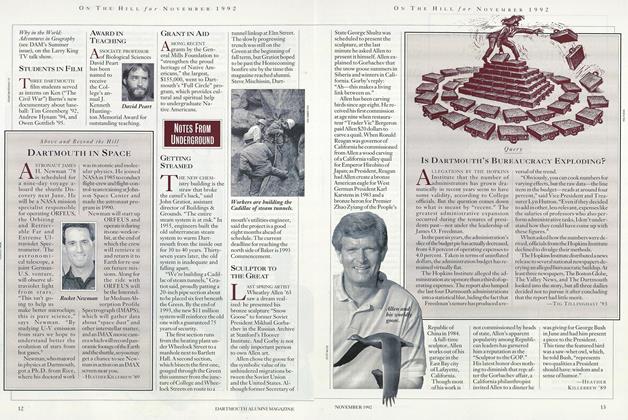

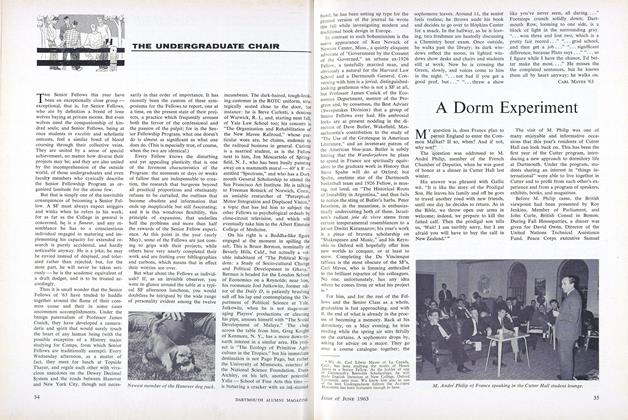

Miss Marta Apy of New Canaan, Conn., a Skidmore sophomore, reigned over Dartmouth's 54th Winter Carnival as Queen of the Snows. Shown with her at crowning ceremony is her date, David N. Elders '63, also of New Canaan, Conn.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePOETRY AT DARTMOUTH

March 1963 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Feature

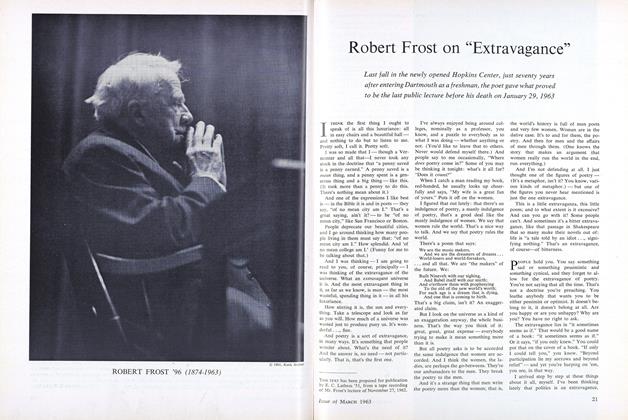

FeatureRobert Frost on "Extravagance"

March 1963 -

Feature

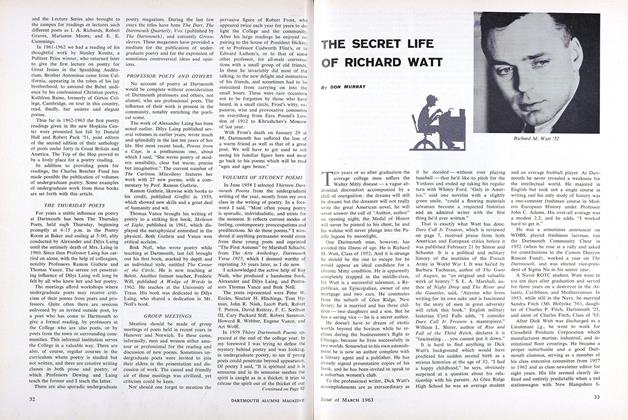

FeatureTHE SECRET LIFE OF RICHARD WATT

March 1963 By DON MURRAY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

March 1963 By JOHN HURD, HUGH M. MCKAY -

Article

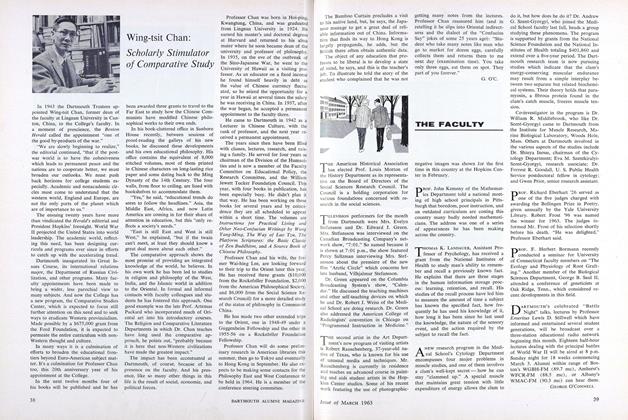

ArticleScholarly Stimulator of Comparative Study

March 1963 By G.O'C. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

March 1963 By CHARLES F. MCGOUGHRAN, ALBERT W. FREY

CARL MAVES '63

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

OCTOBER 1968 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

NOVEMBER 1962 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

DECEMBER 1962 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JANUARY 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

FEBRUARY 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JUNE 1963 By CARL MAVES '63