By Hubert M.Blalock Jr. '4B. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1964. 188pp. $5.00.

This book should be of interest to sociologists, economists, psychologists, political scientists, as well as social researchers in marketing, operations, advertising, community planning, and public and personnel relations. As social scientists they would probably benefit from reading the book because they tend to be hampered in their research by nonexperimental data, weak measuring instruments, and the lack of isolated analytical systems in which the number and type of variables are limited. Blalock writes with considerable clarity about these problems. If for no other reason, the benefit would derive from Blalock's consistent challenges to everyday assumptions and procedures in the collection and analysis of data derived from nonex perimental research, e.g., opinion and behavior surveys, census registration statistics.

Blalock is one of those sociologists who adds to a tradition urged on by Paul F. Lazarsfeld, that sociologists are their own best critics. Not only do these investigators know where to locate the weaknesses of their discipline's methodology and technology, they also assume a constructive posture and suggest alternative solutions to the daily dilemmas of theory construction and empirical research. Within the past few years Blalock has published his constructive criticisms in several professional journals, and now in this book presents a more complete and integrated explanation of many of his ideas.

One of the chief contributions of the book is the spotlight shed on attribute analysis, the treatment of data divided into discrete rather than continuous units. The use of attributes implies an all or nothing condition, a condition which, Blalock maintains, restricts the researcher's freedom in making causal inferences. In most cases the arbitrary "cut-off points" reduce the realism of the data and thus reduce the strength of any causal inference. Blalock has chosen to regard models of causal inference in terms of continuous variables which would include the analysis of categorical data as a special case. His basic approach is to use regression equations and their coefficients in explaining different courses of action in various research problems. The major technique of the book in discussing causal in- ferences is the slope statistic rather than the correlation coefficient which he feels is less suitable since it merely measures unexplained variation.

Blalock's book serves to remind the social researcher that his theories and research results have, to date, not been significantly cumulative and that much improvement is needed in measurement logic and technology. As a result, social researchers should devote more time to manipulating their analytic models in order to better understand the nature of methodological problems. While Blalock does not deal with the issue, this reviewer regards his exposition as supporting the view that social scientists, particularly sociologists, should avoid the temptation held out by officials in government, business and other institutional areas to become expert consultants. Rather, they should spend more time in doing research designed to perfect the processes associated with converting theoretical propositions into operations capable of producing more valid and reliable data than those data which are the current basis of their claimed expertise.

Assistant Professor of Sociology

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

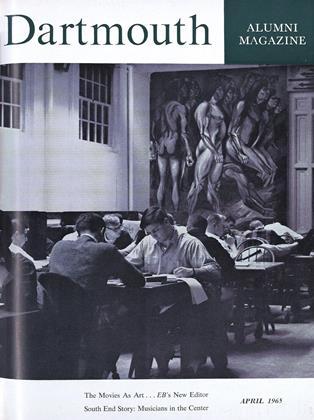

FeatureThe Movies As Art

April 1965 By DAVID STEWART HULL '60 -

Feature

FeatureEB's EDITOR

April 1965 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

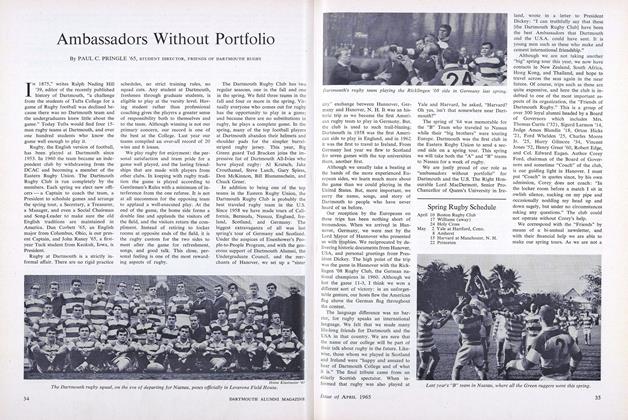

FeatureAmbassadors Without Portfolio

April 1965 By PAUL C. PRINGLE '65 -

Feature

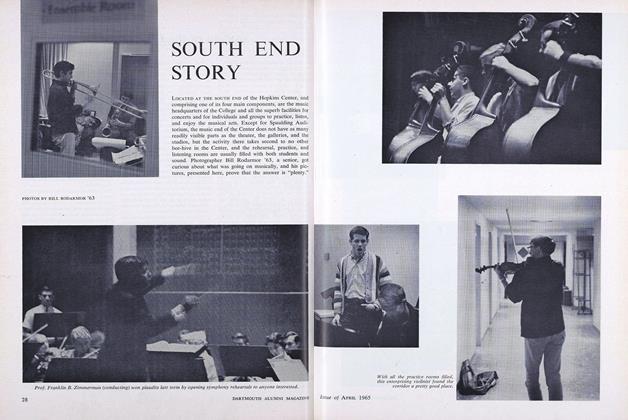

FeatureSOUTH END STORY

April 1965 -

Article

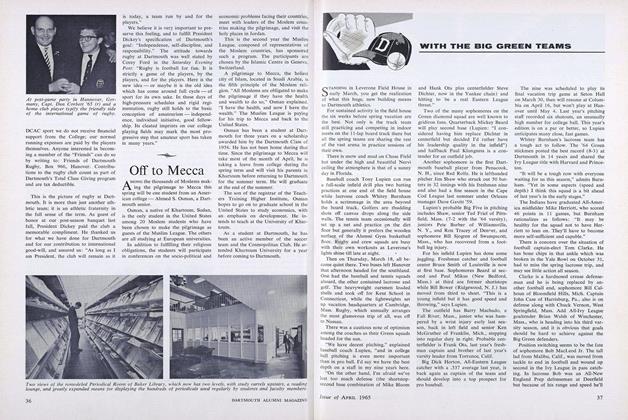

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

April 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleLove-Letter to a College

April 1965 By A NEW ASSISTANT PROFESSOR

Books

-

Books

BooksLEGAL PSYCHOLOGY

FEBRUARY 1932 -

Books

BooksShelf Life

May/June 2002 -

Books

BooksEDITOR'S PICKS

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 -

Books

BooksTHE "DESERT RATS" MUSICAL SHORTHAND SYSTEM

December 1935 By D.E. Cobleigh '23 -

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

December 1934 By Harold G. Rugg -

Books

BooksThe Alchemist

OCTOBER, 1908 By Robert H. Ross '38