PARIS

"Tell me," said the hitchhiking Norman priest as he settled his skirt in the back of our station wagon, "why is your American bread so bad? The crust is nothing and the taste is dull. I have just been in New York, Chicago and Milwaukee - fine cities, agreeable people - but only a glass of water or perhaps, sometimes, one glass of wine at the table."

In fact, he had been junketing, off to a convention of religious music teachers. Like us, he was on his way to Mont-St.-Michel. But for him it was still another junket.

"Of course I like travel," he said. "Now I go on a pilgrimage for peace, peace in Vietnam. I myself don't see much in that. I suppose if you Americans leave, the Communists will take over. Perhaps our organization has some leaders from the left. But tell me, is it your impression that American girls who attend convent schools are more or less chaste than those who do not?"

A priest out of Rabelais, of course. But also a man very much at one with his fellow Europeans, generally comfortable, mobile, and largely indifferent to ideology. The central feature of present-day Europe, both east and west of what used to be called the Iron Curtain, is its comparative affluence. In nearly every country and in nearly every income bracket, people are living better than they ever have before. Despite prices that have risen alarmingly in "miracle" nations like Spain and Yugoslavia, most states have been managing their affairs well enough so that everybody expects and receives gains in real income every year. Only the Czechs, still recovering from the mismating of central direction and an advanced industrial economy, and the British, restraining growth to preserve a mystical exchange value, fall outside this rule.

A Greek businessman in Athens points to the noisy chaos in Syndagma Square and boasts: "That's progress. Ten years ago, we weren't rich enough for a traffic jam like that." To be sure, cars are still beyond the reach of all but a narrow slice of Greek society. But in France, factory workers are turning in motor bikes for Citroen Deux Chevaux and in Northern Italy better-paid blue collar families drive little Fiats.

FIFTEEN years of virtually uninterrupted gains in income - recession in Europe means output growing at only two percent instead of five- have changed many ideas about spending and saving. The frugal middleclass saver with his horror of debt is disappearing. His successor spends what he earns on TV and travel, begins to think that buying on credit is not the devil's invention, and looks for his gratification in this world. The new affluence, of course, is distributed with something less than an even hand. The Dutch computer programmer is increasing his income much faster than the small German farmer. Speculators in French and Italian real estate have far outdistanced both. But the point is that everywhere there now exists a confidence in growing incomes that no government can afford to neglect for long. Even in Eastern Europe, Communist regimes are responding to this barely articulated pressure. More resources are devoted to consumer goods and targets are shifted to improve their quality. In the West, all governments, regardless of political label, are Keynesian. They are not only committed to full employment, they produce it with government spending when private demand falters. In fact, private demand doesn't falter very much. Most governments worry more about restraining spending to choke off price increases than they do about enlarging it to expand jobs.

Still, affluence in Europe's richest states has not raised living standards to more than two-thirds of the American level. Housing is desperately short nearly everywhere except in Belgium. Three of five French dwellings were constructed before World War I. Italy has built magnificent autostradas but, as American tourists know, the secondary roads are a tortuous nightmare. School construction is way behind needs in most countries. For all the new sophistication in economic management, there are pockets of unemployment in Scotland during Britain's best periods and large belts of joblessness all along the Mediterranean.

Even so, the consumerized, homogenized society is spreading rapidly. Television aerials sprout everywhere, from apartment buildings, farmhouses and roadside inns. Four of five British households have a set, seven of ten in Sweden, six of ten in Germany, nearly half in Italy, and three of ten in France. Supermarkets are thriving in no-nonsense Switzerland and Germany. Even in France, the tiny neighborhood retail shops would be in deep trouble if the government would permit les supermarches to expand as fast as they want.

EASTERN Europe, of course, is something else again. It is only in the last few years that Communist states, one after the other, have begun to accent consumer production. Nevertheless, living standards throughout the region are generally tolerable. It is hard to find sober students of the area who think the stability of any of these regimes is threatened on economic grounds. Perhaps the most important political developments in the East are the deals that Fiat and Renault are arranging to build autos in the Soviet Union, Bulgaria and Poland. For two generations, Communists have insisted that the private car was the essence of bourgeois individualism. Moscow city planners used to tell visitors they didn't have to worry about parking problems because public transportation would have a continuing monopoly. Now all this is changing. In ten years the Soviet Union will be producing more than one million cars a year. It will also have to build highways, provide gasoline, invest in service stations, motels and all the other paraphernalia that the new car class will demand. In a way that De Gaulle never realized, the notion of a single Europe from the Atlantic to the Urals is really in sight.

In the new leisure civilization growing up here, travel is the fastest growth industry. Try to do business in Western Europe during August; nobody is at home. Cold cash, not fancy, has led the Rothschilds to finance a string of vacation clubs for restless young people all around the Mediterranean. Airports at hubs like Dusseldorf, Paris, and Rome are frantic throughout the year. Even the French, who like Bostonians saw little point in traveling because they were already there, are venturing abroad. European countries received 75 million foreign tourists last year and the vast majority were fellow Europeans. Sixteen percent of the Dutch take vacations abroad. So do thirteen percent of the Germans and Swedes and eight percent of the French and English. It is not entirely clear that this generates nothing but undiluted goodwill. The Paris couple who turn up their noses at the taverna fare in Athens or the camera-laden German who bulls his way to the head of a line at a French chateau are something less than national advertisements. Even so, a subtle and non-political cosmopolitanism flows from this experience. Its impact on both host countries and visitors is like the spread of consumer goods. The differences are being worn away.

NOR is all this motion exclusively a middle- and upper-class affair. Workers from the poorer southern tier have been moving to the labor-hungry north in large numbers ever since Europe completed its postwar reconstruction. Italians, Spaniards, Portuguese, Greeks, Turks, Yugoslavs, and North Africans have poured into Switzerland, Germany, Britain, and France. Many do the work that their newly affluent hosts won't touch sweeping streets, laboring on road gangs, working as domestic or hotel servants. But some of the more than four million immigrant workers, particularly those in Germany and Switzerland, have found factory jobs and new skills. The old European xenophobia and class prejudice shows itself at its worst in the treatment of these migrants. International codes are supposed to govern their treatment, but they are often badly housed, generally looked down upon, and kept rigorously outside the main social stream. Despite this second-class existence, the immigrants often go home with a new and liberating perspective. They have seen freer, richer societies and acquired a taste for better lives. In Spain, for example, the combined force of returning emigrants and tourists is slowly transforming a once-rigid dictatorship. Movie billboards now display some cleavage, Lorca's formerly forbidden plays are shown, and the press is getting a mild dose of freer expression. At the same time, the money that Greeks and Spaniards abroad send back to their families is a far from unimportant item in the rapid growth of both nations.

The wave of well-being, both East and West, is drowning the cold war and burying ideological differences. The most dramatic example is the talk in Eastern Europe of introducing free market elements into command economies. Apart from Yugoslavia, all this is still more talk than action but that is hardly surprising. Veteran bureaucrats throughout the East rightly feel their power is threatened when factory managers have a freer hand. But the talk goes on and so do some of the liberalizing experiments. A Czechoslovakian chemical plant has fewer targets to meet and its principal criterion of performance is the profit it earns. The Hungarian drug trust is allowed some leeway in pricing. In Yugoslavia, firms now have considerable freedom to determine how they shall invest any surplus. High officials in Belgrade are even talking of a socialist capital market to transfer funds more efficiently from industry to industry and region to region. None of this changes the essential quality of property. Productive means are still controlled by the state. But the new search for a more efficient allocation of resources and the new emphasis on better quality goods is slowly changing habits and institutions.

The Curtain's breakdown is most evident in the big hotels of the Eastern capitals. A steady parade of businessmen and bankers from Britain, Germany, and France comes to Prague, Warsaw, and Budapest to do a deal. The Eastern Europeans are so eager to welcome them that bars equipped with complaisant young ladies are allowed to operate for Western clients. All this is eroding the landmarks of the cold war. In West Germany, for example, business pressure and popular sentiment are leading Bonn to search for ways to shrug off the Hallstein doctrine. This is the rule, not always honored, that prohibits diplomatic relations with any state recognizing East Germany.

A fluid Europe, in motion both politically and economically, is rolling over some of the most cherished notions of American policymakers. The grand design - tightly integrated anti-Communist Western Europe, shielded by a common defense and closely linked to the United States in an Atlantic Community — is fading. The pressures are mostly in the opposite direction. In Washington, there are officials who still think these pressures are generated solely by the bitter chauvinism of General de Gaulle. But he reflects as much as he creates a growing mood.

There are increasing signs that the Common Market will not become, as its planners intended, a supranational grouping of anti-Communist states. The Community is already negotiating to bring in neutral Austria. Even so strong a supporter of American policy as Chancellor Erhard in Germany has urged the Market to embrace neutral Sweden as well. This, as well as de Gaulle, weakens the ideological gloss of the Market's founders. It also makes dealings with Communist Europe much easier. And that is an objective that looks increasingly attractive here.

In defense affairs, Western Europe's officials talk with something less than a consistent voice. Except in Bonn, politicians almost everywhere say in private that they no longer believe in a Russian threat, no longer fear invasion from the East. In public, they match opinion with deeds in part by working to cut down the troops and arms they are supposed to supply to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. The French departure from NATO's military side is only an extreme expression of a position towards which NATO's other members are tempted to drift. Nevertheless, the Europeans want to play it safe. They still seek assurance that the United States will come to their aid with nuclear power in case the calculation about the East is wrong.

But even here there are hints of change, a suggestion that American support is more provocative than protective. Just the other day, the Liberal Party in Britain, traditionally in the ideological center, was upset by a revolt of Young Turks. They defeated a resolution that would have condemned France for disrupting the Alliance. If this means anything, it is a clue that a younger generation, neither of the right nor of the left, thinks institutions like NATO are no longer relevant.

There is one underlying, unifying political strain in Europe: fear of Germany. East and West, the memories of German adventurism and barbarism persist. A leading Gaullist is twitted because the planes carrying France's force de frappe must refuel over Poland. He replies, only half-jokingly, "They only need to fly as far as Germany." Even in Warsaw, a foreign office aide tells visitors he is not entirely pleased over the disarray inside NATO. What if this simply turns loose an aggressive Germany, he asks.

Indeed, this is the strongest argument that the "good Europeans," those who still seek a tightly knit Western community, can make. Break down the postwar structures, they argue, and you revive nationalism in Germany. There is surely something in this. The recent revolt of Bonn's generals was due in part to a frightening frustration. In a unified Western Europe, they saw a role for themselves. But as Europe's unity fragments and the United States talks of an accommodation with Russia to curb nuclear weapons, the generals see themselves without a real function. Nevertheless, the generals don't run Germany now. As far as a sometimes visitor can see, militarism in Germany hasn't much of a future. If German citizens are obsessed with anything, it appears to be food, homes, television, cars, and travel. This impression is reinforced by the polls. When Germans are asked, "Do you want nuclear arms?," most have replied repeatedly, "count us out."

ANYONE who talks to politicians L across the Continent today is struck by one phenomenon. Twentyone years after the war, Europe is ripe for a peace settlement. This, of course, means settling Germany's future. Today, in both East and West, there is a tacit understanding that the treaty must contain three principal elements and a surprising agreement on their content. The elements are these:

One — West Germany must recognize the present Eastern borders and explicitly give up any claims on what is now Poland. Nobody wants or expects to redraw Europe's borders at this date.

Two — No nuclear role for Germany, no matter how disguised. This, of course, does mean that Europeans think Germans are different and should be discriminated against. Reasonable or not, it reflects a deep-seated suspicion fed by a century of German ambition. If the polls can be believed, this condition may not be as hard for a German government to swallow politically as some American officials think.

Three - The gradual coming together of the East and West German regimes, ultimately creating a single, independent state. This is the bone in Communist throats. But unpalatable as it is to the East, politicians there recognize that the first two conditions won't be achieved without the third.

The arguments go on over how to bring this settlement about. But it is increasingly evident to many Europeans that the tight and exclusive arrangements of the postwar period can't further it. This is another and central reason for all the centrifugal motion and increasingly independent orbits of the European states. For the near future, then, it is hard to visualize a unified Europe on the American model. This forecast of national states, sometimes cooperating and sometimes not, may be less glorious than dreams of a United States of Europe. But apart from General de Gaulle, few politicians and fewer citizens are much concerned with glory these days.

This comfortable view of things accounts in part for the European mistrust of the United States in Vietnam. Again, only de Gaulle speaks out openly. But again, he is not completely out of touch with Continental sentiment. In Britain, for example, the Labor government publicly supports American action and in private British officials deplore it. The strongest verbal backing in Europe comes from Bonn. But when some of the Bundestag legislators began to suspect that Germany might send fighting men to Vietnam, the ruling Christian Democrats had to give strong assurances that this was not so.

It is imprecise and even arrogant to talk of a single "European view." Right-wing newspapers in France and Italy, to cite some, frequently proclaim that the United States is defending civilization from the yellow peril in Southeast Asia. But if there is a prevailing view across the Continent, I think it is that the United States has become trapped in a senseless, ruthless, profitless engagement. Moreover, Vietnam has had a fallout effect on some of the Europeans' most cherished projects. For one thing, it has blocked the East-West settlement that now seems ready for the making. The Soviet Union apparently thinks it can make no important arrangements with the United States until the war dies down. And nobody in Europe, including General de Gaulle, believes a Continental peace treaty can be drawn without American participation.

In Washington, Europe's view of Vietnam is dismissed as insular and self-centered. Here, however, it fits the kind of a world the Europeans seem to be making, relatively comfortable, generally civilized, and more or less tolerant.

"Les supermarchés" are changing shopping habits all over Paris.

The good life in Rome: sidewalk cafes on the fashionable Via Veneto.

Cars crowding the Kaiserdamm indicate West Berlin's prosperity.

THE AUTHOR: Bernard D. (Bud) Nossiter '47, pictured taking a coffee break on the Champs filysées, is based in Paris as European correspondent for The WashingtonPost. He writes: "I ramble across Europe (with some sidetrips to North Africa and the Middle East) concentrating on economic stories with a dash of politics and cultural pieces on the side." He went to Paris in 1964 after nine years as national economics correspondent for the Post. Last spring he won the Overseas Press Club award for the best business reporting from abroad, an honor added to the Christopher Award for a feature article in the old New York WorldTelegram, and a Sigma Delta Chi award for distinguished Washington correspondence in 1961. He also won a Hillman Foundation prize for his book The Mythmakers: AnEssay on Power and Wealth, written in 1962-63 while he was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard. Nossiter took his M.A. in economics at Harvard after graduating from Dartmouth, then had brief stints with the Worcester Telegram, WallStreet Journal, and Fortune. He was a general reporter on the World-Telegram for three years prior to joining TheWashington Post in 1955. Bud and his wife Jacqueline, with four sons, live in an old Paris house near the Étoile "that's long on charm and peeling plaster."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

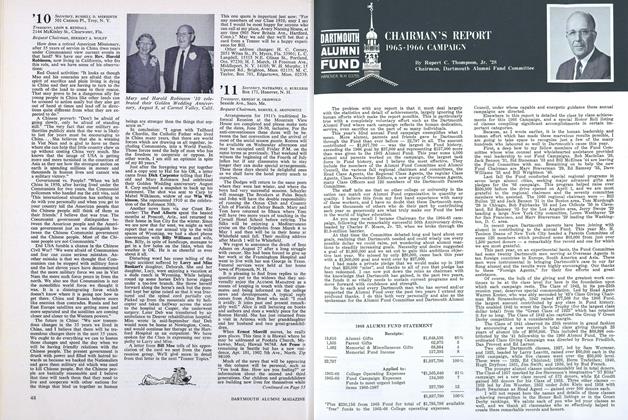

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1905-1966 CAMPAIGN

November 1966 By Rupert C. Thompson. Jr. '28 -

Feature

FeatureTHE RACE TO BE HUMAN

November 1966 -

Feature

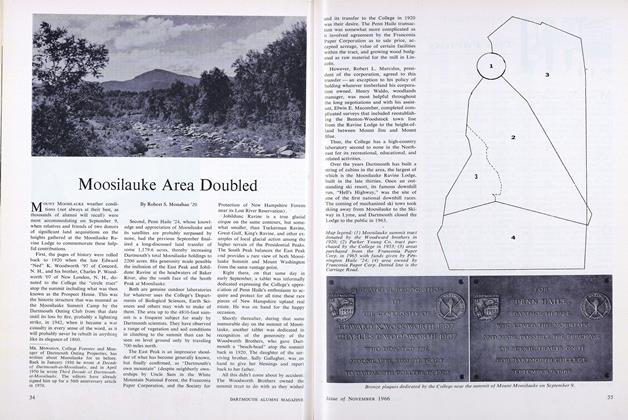

FeatureMoosilauke Area Doubled

November 1966 By Robert S. Monahan '29 -

Feature

FeatureFederal Judge

November 1966 -

Feature

FeatureNorth Country Doctor

November 1966 -

Feature

FeatureJob Corps Director

November 1966

Bernard D. Nossiter '47

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryRIDE of a LIFETIME

May/June 2013 -

Feature

FeatureA Scientific Centennial for Dartmouth

OCTOBER 1969 By ALLEN L. KING -

FEATURE

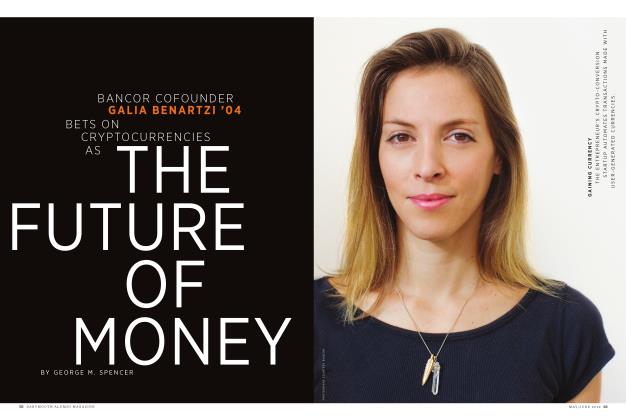

FEATUREThe Future of Money

MAY | JUNE 2019 By GEORGE M. SPENCER -

Feature

FeatureTHE EXPERIMENTAL THEATRE

June 1954 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Feature

FeatureNative America at Dartmouth

APRIL 1997 By Karen Endicott -

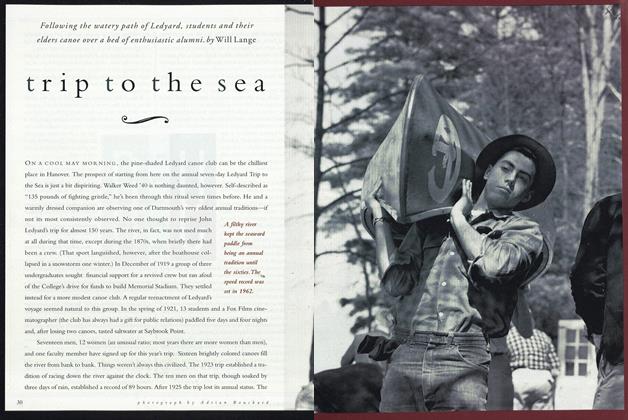

Feature

FeatureTrip to the sea

June 1993 By Will Lange