THE SHARING SOCIETY

by Edward Lamb '24

Lyle Stuart, 1979. 272 pp. $12.

Edward Lamb is Dartmouth's richest radical or its most militant multimillionaire. Either way, he is a unique combination of maverick and wheeler-dealer, a genuine idealist and down-to-earth businessman, who derives equal pleasure from struggling for causes he believes will liberate men or from a transaction that will yield him another few million in capital gains. It is unlikely that Fidel Castro has another friend like Lamb, who has been enormously successful in exploiting a system for which he has a profound distaste.

His engaging book a series of loosely connected reflections on the ideal society interspersed with anecdotal reminiscence is as singular as the man himself. The common thread is Lamb's appetite, his zest for life, an overflowing vitality that sends him on frequent if starry-eyed visits to the Soviet Union as well as into the marketplace where he has won control of an empire whose assets he estimates at $600 million. Lamb began his professional life as a labor lawyer, made a fortune in broadcasting, another in manufacturing and a third in banking. At every step of the way, he was further convinced that an unplanned system based on private property is not only immoral but inefficient.

His twin gods are V. I. Lenin and Frederick Taylor, the father of what is called scientific management. He admires equally the Soviet commissar and the brighter graduates of the better business schools. If only they could be fused, he suggests, Utopia would soon be at hand.'There is an echo of Thorstein Veblen in this and, indeed, there is much in Lamb that recalls an earlier, simpler time.

Despite his frequent trips to the Soviet Union, Lamb has apparently seen no Gulags, talked with no dissidents, heard nothing of ordeal by psychiatry, and pointedly notes that nobody in Russia ever censored him. (Why should they?). Instead, he finds production "adjusted to the needs of the community," a place "where work is meaningful and dignified," where "every person is guaranteed a livelihood." Lamb has heard that others have raised "nitpicking" criticisms about the absence of personal liberty in the "socialist societies." But then American Indians and other minorities suffer here; anyway, in the "socialist" world, "Human rights to food, shelter and jobs are also important."

This sort of thing will provoke some outrage. But it is so palpably naive and blinkered, so inflected with wishful thinking, that it need not give offense. Lamb is a throwback. To read him is to make a nostalgic return to the days of the Popular Front, when there were no enemies on the Left and Moscow trials dealt only with agents of fascism.

Lamb, a lawyer, does not argue or build a case. He simply asserts. He has been there. He knows. He has, for example, a healthy con- tempt for bureaucrats but does not feel impelled to discuss the bureaucracy of.the planned society he seeks. (To be sure, Lamb might welcome indicative planning, that interesting Western European technique of target setting for microeconomic matters by business, labor, and government blended with fiscal and monetary policy on the macroeconomic level. But Lamb is untroubled by distinctions and there is nothing in what he writes to suggest that he wants anything but the full-blooded Soviet variety.) He has a deep distaste for the ideological police of the F.B.I, and the C.I.A. who tried to strip him of his broadcasting stations. He has neither space nor time for their counterparts in the "socialist" world. There is something touching in all this.

The strength of his book lies in the anecdotes. There is the splendid story of Lamb spending $900,000 in legal fees, to fight successfully against the false charge that he had been a Communist Party member. He makes the F.B.I, and the C.I.A. sound like Keystone cops, roles they have played more than once. There is Lamb, the admirer of scientific managers, telling one on himself, taken for a ride by a slick operator with all the surface credentials. Lamb also rides with Castro as an assassin's bullets narrowly miss them both. Lamb lectures Castro, who takes 50 pages of notes on the American's wit and wisdom. There is even a Lamb formula for making money: first, you gain access to a million dollar line of credit. . . .

Running through these idiosyncratic pages is a current of energy and individualism. The man who wants an ordered, planned society is forever standing up against the crowd. No matter how wrongheaded or simplistic, there is something quintessentially American about Edward Lamb. A free enterpriser in business and politics, he is a warm-hearted, good-willed original.

Longtime European correspondent for the New York Times and author of a recent socialhistory, Britain: A Future that Works, BernardNossiter is now chief of the Times' UnitedNations Bureau in New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

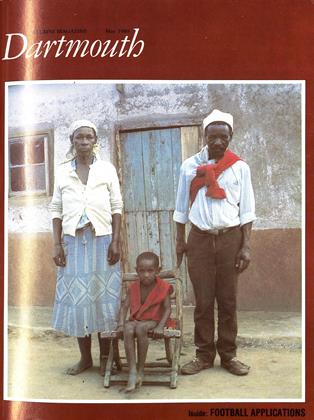

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureIn Another Country

May 1980 By Beth Ann Baron -

Article

ArticleAlchemist in Miniature

May 1980 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleScientific Humanist

May 1980 By M.B.R -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

May 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticlePainting Medicos Have Both "Life" and "Work"

May 1980 By D.C.G

Bernard D. Nossiter '47

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1983 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

JUNE • 1986 -

Feature

FeatureNotes on the New Europe

NOVEMBER 1966 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47 -

Article

ArticleOff to a Good Start.

DECEMBER 1982 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47 -

Books

BooksThe Nuclear Dilemma

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1983 By BERNARD D. NOSSITER '47

Books

-

Books

BooksAlbert W. Levi '32, is the author

December 1933 -

Books

BooksAlumni Notes

July 1947 -

Books

BooksWILD TRAIN: The Story of the Andrews Raiders

January 1957 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksMoral Sanitation

December 1916 By JAMES L. MCCONAUGHY -

Books

BooksREADING THE SONG OF ROLAND.

JULY 1970 By STEPHEN G. NICHOLS JR. '58 -

Books

BooksTHE TRUMPETER OF KRAKOW

December, 1928 By W.R.Pressey