United Nations Bureau Chief, New York Times

Before a packed, attentive audience in the Spaulding Auditorium, Vladimir Petrovsky of the Soviet foreign ministry firmly insiste'd that only a climate of detente could create negotiations to end the nuclear arms race. Hendrik Wagenmakers, a Dutch disarmament specialist, tartly replied: "Detente is a menu; not a la carte." It includes a respect for human rights that, he implied, was conspicuously absent in the Soviet Union.

Carmen Moreno of Mexico's foreign ministry pleaded for "an economy based on justice and equity," qualities she and other third world officials believe can be found in a New International Economic Order. Hamilton Whyte, deputy delegate of Britain's United Nations Emission, dismissed this as unreal, "a level of generality that is virtually meaningless." Instead, he called for a shift on western resources from obsolete industries to more productive, technically advanced uses.

The tone was polite; these were experienced diplomats visiting Dartmouth, most with the rank of ambassador. But the differences were real and unmistakeable. East and West hold a sharply different view of managing arms cuts; North and South see the causes of the world's stagnating economy in an opposing light. The professionals who flew to the Hanover plain on November 5 illuminated the clashing points of view.

Their exchanges in Spaulding provided a fitting launch for the John Sloan Dickey Endowment which aims, in classrooms, in the field and through research, at greater understanding of international conflict and cooperation. Instead of setpiece speeches, the Dartmouth community heard and took part in two panel discussions. The day was a laboratory demonstration of some of the great quarrels now dividing the world. John Dickey is identified with Great Issues; had he been able to attend, he would have been pleased. His idea of education was reborn in Spaulding for undergraduates, faculty, townspeople and 210 foreign high school exchange students brought to Hanover by the American Field Service.

The day began with a luncheon in the hangar-like Alumni Hall of the Hopkins Center. There, Hans Penner, the Dean of the Faculty, observed the paradox behind the search for security and prosperity: man's technological grasp has exceeded his political reach. The new Dickey Endowment, he said, attempts nothing less than a curriculum to "liberate us from cultural relativism." Rob Stein, president of the Undergraduate Council, spoke of "naive preoccupations which prevent us from understanding," and suggested that the endowment could help Dartmouth students "become conscious and contributing members of the world community."

The two Spaulding panels then underscored some of the disarray in the world community. The world economy "is something of a mess," began Kyung-Won Kim, head of South Korea's observer mission to the U.N. His matter-of-fact language set the style for the day. The United States, he argued, is so powerful that it exercises a virtual veto over expansion and contraction in the rest of the world. In effect, he called on Washington to get on with its anti-inflation drive and move to policies that would promote global investment again.

Many participants pointed a finger at the U.S., and Kim said he had heard "some rhetoric in the election that was scary," demands by Congressional candidates to spare American industry from competing imports like those South Korea has begun to develop. He questioned whether "protectionist instincts will be answered by rational selt interest."

Whyte of Britain was asked by a young woman, "What can we do?" He was blunt: U.S. citizens should tell the Reagan administration not to cut back on foreign aid and particularly its contribution to the International Development Association, the soft loan window of the World Bank. But Whyte was concerned chiefly with the traditional, stagnating western industries whose products are now produced more efficiently in South Korea and other newly industrializing countries. We can't simply hand over resources to the poor nations, he said, but we must somehow work out ways of moving capital, management and labor from these outmoded industries to the more productive ventures in high technology and services.

Moreno, Mexico's director general for multilateral economic relations, repeatedly called for a start on the long-stalled global negotiations. The third world hopes they will produce deals to push up prices of raw materials, expand aid and give Asia, Africa and Latin America a bigger voice in institutions like the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. The developed world, she contended, won't recover without enlarging markets among its third world customers. She attributed her own nation's debt crisis to falling commodity prices and the high U.S. interest rates.

The second panel, on peace and security, began with a challenge. J. Alan Beesley, Canada's disarmament negotiator at the U.N., quickly dismissed the Soviet Union's recent declaration that it would never be first to use nuclear weapons. The U.N. charter prohibits any use of force, Beesley observed. So to promise abstention with one weapon is to imply the legitimacy of the first use of force with another, degrading the charter.

Echoing Dean Penner, Beesley said that, "Technology is the central agent of the problem. All new weapons systems are potentially destabilizing" since they increase the danger that some nation will be tempted to strike first. To stifle technological advance in nuclear arms, Beesley called for a complete ban on tests, including test flights. Underground nuclear tests are still permitted; in the view of Canadians and others, no new weapons can be produced if all tests halt.

His fear that the danger of nuclear war has increased was repeated by the Netherlands' expert, Wagenmakers. There is no international order, he said, and the world increasingly resembles a jungle. There was a measure of stability when only two centers of power existed, the Soviet Union and the U.S. Now, there are several centers and global anarchy threatens. More than ever, there is the prospect that some marginal event could trigger a nuclear holocaust, Wagenmakers said.

Petrovsky, a member of the collegium that directs the Soviet foreign ministry, shared some of his colleagues' views. The danger of nuclear war has increased and even the thrdat of an accidental war, touched off by a computer that wrongly signalled an incoming missile. Apart from the need for detente, he insisted on the importance of Moscow's renunciation of a first strike. He called it, "a drastic step to restore trust; it helps to create a climate." It was now up to the West to respond.

Petrovsky was pessimistic about the present negotiations to curb strategic weapons and nuclear missiles in Europe. They are "like art for the sake of art," he said, and questioned whether they would yield "practical results." But he did find some common ground with Beesley and said that a freeze in the development of nuclear weapons would be helpful.

One of the most re- spected envoys at the United Nations is Olara Otunnu of Uganda who was inventive enough to break the deadlock last year over the search for a new Secretary General. As a member of the Security Council, he has watched big power rivalry at first hand. So Otunnu said that the world's insecurity can be traced to Washington and Moscow. "The major responsibility for the present state of affairs rests with the permanent members (of the Council) and especially the two superpowers."

The debate went on informally that evening, first over drinks in Sanborn House, later at dinner in the 1902 Room, its austere tables transformed by damask, crystal and animated talk. President David T. McLaughlin announced that the Dickey fund had collected S3 million of the $10 million it seeks. He then formally launched the endowment, saying that Dartmouth's trustees have voted to establish "a program to honor John Dickey by assuring that Dartmouth undergraduates will develop an international perspective to guide their lives in this increasingly complex world community."

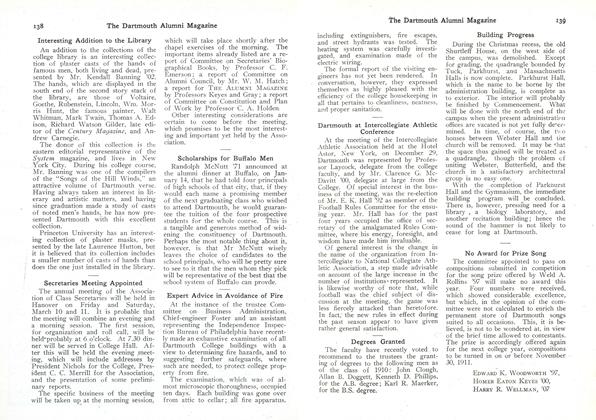

The symposium in session in Spaulding Auditorium

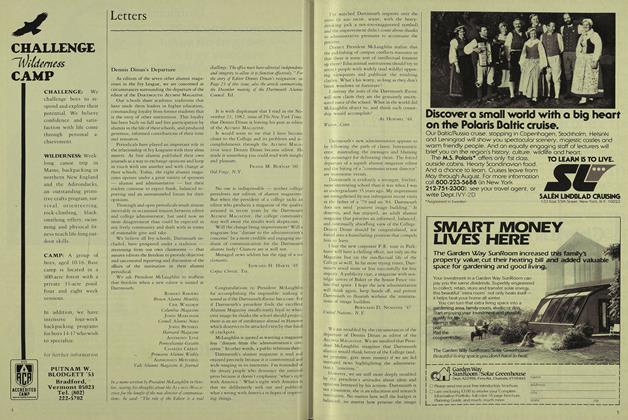

Members of the panel on Peace and Security: Vladimir Petrovsky (U.S.S.R.), HendrikWagenmakers (Netherlands), Alan Beesley (Canada) and Olara Otunmt (Uganda)

Vladimir Petrovsky with students at the reception-discussion following the symposium

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOn Building Community

December 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWhere They Hang Their Hats

December 1982 By Steve Farnsworth and Jean Korelitz -

Feature

FeatureWindows on a World

December 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in the World

December 1982 -

Article

ArticleRound the Girdled Earth...

December 1982 -

Article

ArticleTHE DICKEY ENDOWMENT

December 1982

Bernard D. Nossiter '47

Article

-

Article

ArticleInteresting Addition to the Library

February, 1911 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Concert

February, 1911 -

Article

ArticleCAMPAIGNS BY THE CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATION

April, 1914 -

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES APRIL 27 AND 28

April, 1923 -

Article

ArticleJune Reunion Meetings

APRIL 1968 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse

NOVEMBER 1991