As an English major at Dartmouth, CHARLIE MAYO '32 studied writing under the late and much beloved Sidney Cox and read Herman Melville's MobyDick. Mayo thought then he might become a writer or teacher, scarcely dreaming that like Captain Ahab he was destined to roam the ocean seas not in search of the white whale, but in relentless pursuit of the giant tuna, becoming "the finest tuna skipper on the Atlantic Coast" (Sports Illustrated, Dec. 3, 1962).

In that same article he was cited as "a poet and philosopher by training, a scientist by instinct, and a fisherman by birth and choice."

So we set out one bright September day, driving down to Provincetown, on the tip of Cape Cod, where Mayo resides and where he was born. Provincetown has changed a lot in the past few decades and Mayo views the changes with mixed emotions. Right next door to the modest home he built by himself is an 80-unit motel. Across the street the Mayos have their own boarding house The Cape Codder - so tourists help as they do with Mayo's charter fishing trips.

Several years ago a National Educational Television crew came down to do a film feature on Mayo, but he gave them such an interesting account of the changes in his hometown that they switched signals and did a documentary instead on the urbanization of Provincetown.

Mayo usually docks his boat, Chantey Ill, at one of the main piers jutting out into Provincetown harbor off Commercial Street, but the day we were there Hurricane Doria was threatening and he'd cautiously moved the boat to Wellfleet just south where there's a protected harbor. It was from Well- fleet that we headed out into Massachusetts Bay one morning in search of the elusive tuna.

"Come on and step up into my office," said Mayo as he chugged out of Provincetown harbor. Mayo's "of- fice" is the flying bridge of ChanteyIll, housing the wheel, controls and radios, where he can scan the ocean ahead for signs of tuna, while glancing back occasionally to make sure his mates are baiting up correctly and that his charter fisherman is ready for action.

Mayo wastes no time going to work. While he guides Chantey III to sea, he's talking by radio-telephone, over the maritime band, with skippers of other boats, seeking information on wind, weather, and fishing conditions in their areas. Before we'd scarcely cleared the harbor, Mayo had already found out how things were off Nantucket, off Gloucester, and out of Boston harbor. No tuna had been sighted anywhere for the past four days, but Mayo speculated that heavy seas, caused by the fringe of Hurricane Doria, might have driven the tuna deep.

"Tuna are never easy to find," Mayo said. "Sometimes you go three or four days without seeing a trace of any, and then suddenly you'll hit into a school of them. We've boated three or four giants in one day."

By now the two mates have hooked up all the baits and lures and ChanteyIll is trailing three lines of multiple baits astern. Mayo has pioneered the multiple bait, skip line technique, using squid, mackerel, and even lures on three lines so that a following tuna has quite a variety to choose from.

Mayo kept his baiting techniques closely guarded for some years, and other tuna sports fishermen used to shadow his boat, watching every move through binoculars in an effort to learn his secrets.

"It got to be too much to have all these boats following and watching me," Mayo said, "so I finally just told them what I was using, although I did hold back some information on how to hook up and the combinations we use."

Although bait is important in tuna fishing by rod and reel, a great deal more depends on the boat and its crew. Over the past decade Mayo and his crew have helped anglers win ten Governors' Cups awarded for the largest tuna caught in Massachusetts waters by rod and reel. A few years back Chantey Ill brought back 78 tuna from 85 days' fishing. This year the erratic summer weather slowed the pace, but Mayo's charters brought in some two-dozen tuna, none less than 500 pounds. A week before our visit Mayo's son Stormy (Charles A. Mayo Ill '65) snagged a 791-pounder, while earlier in the season one angler wrestled an 840-pound tuna to boat. Stormy is a graduate student in marine biology at the Institute of Marine Science in Miami.

"Charlie's much too modest to tell you how important the handling of a boat is in catching tuna," his wife Ing told us one evening over a delicious tuna steak dinner. "Once that tuna rushes in and grabs the hook, the boat has to be ready to move backwards or forwards, go to left or right in a split second. A fighting tuna can take off like an express train and you have to go with him or lose the line."

According to tournament rules, once an angler has hooked a tuna he must fight him until the fish is boated or he is lost. One man fought his tuna for a long nineteen hours. This past summer another angler kept falling asleep in the fighting chair. "How can a man fall asleep fighting a 700-pound tuna?" Mayo asked querulously. "But that's what he was doing and my mates had to keep putting wet towels around his neck to keep him awake."

Mayo has been going after tuna for thirty years and probably knows more about them and their habits than anyone else. He's kept a full record on his catches time of day, wind, water temperature, tide, general location, other types of fish around. Until recently he carried this information around in his head and in a small notebook. Last year he and Stormy began a systematic process of putting all this data on punch cards.

"I'm not sure how this will work out," he admits. "I don't think fishing for tuna can be really reduced to data processing, but so far it's been a helpful check to confirm my own observations and recollections."

Mayo's roots go deep in New England soil, and some of his ancestors date back to the Pilgrims. His father was a fisherman, working out of Provincetown in the early part of this century. "Dad and I used to row double in a dory, putting out fishing nets in all sorts of weather," he recalled. "You can really get to know a father when you work together like this in a small boat on the ocean."

Mayo came to Dartmouth from Provincetown High, helping to pay his way through college by taking tourists on trips out of Provincetown during the summer months. "I wanted an out- of-doors college," he explained, "and Dartmouth was just right for me."

"I missed the ocean though. That first year at Dartmouth I'd wake up in the morning thinking I could hear the surf, but it turned out to be the rattle of dishes in Freshman Commons."

Following graduation from Dartmouth, Mayo bought a boat and began taking charter trips out from Province- town in the summer and from Florida to the Bahama Islands in the winter a routine he has followed almost every year since 1932.

During World War II days, Mayo worked for a while under Nelson Rockefeller '30, helping to design ships for the South American trade. Later he served as an expert on PT hull design and maintenance for the Navy.

Despite his keen preoccupation with tuna fishing, Mayo is deeply interested in politics, international events, and contemporary society. "People talk with scorn about today's youngsters the beats, the hippies, and those rebelling against society," he says, "but we shouldn't blame these young people too much. We've made a real mess of things and you can't condemn them for not liking much of what they see and hear." He believes every man should be free to go his own way, providing he doesn't hurt others.

From time to time some of Mayo's charter fishermen have urged him to write a book. "Maybe some year I'll take a winter off and try it," he says. "I thought I might call such a book Flights from the Flying Bridge."

For the past twenty years Mayo has also spent many hours in reading and research on the habits of fish and the ways of the ocean. He has been a consultant for the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute and has worked with several authors on books dealing with tuna and other fish in the Atlantic. On his living room table one finds reports of all types published by scientific organizations and the fishing industry.

Mayo has an abiding affection for Dartmouth and many Dartmouth friends. President Dickey has talked with him on several occasions about fishing.

If Flights from the Flying Bridge is ever published, it should be quite a book. But if one really wants to get to know Charlie Mayo and maybe even capture a giant tuna, by far the best way to do is to sign up the Chantey III and take to the high seas with one of the finest skippers in the business.

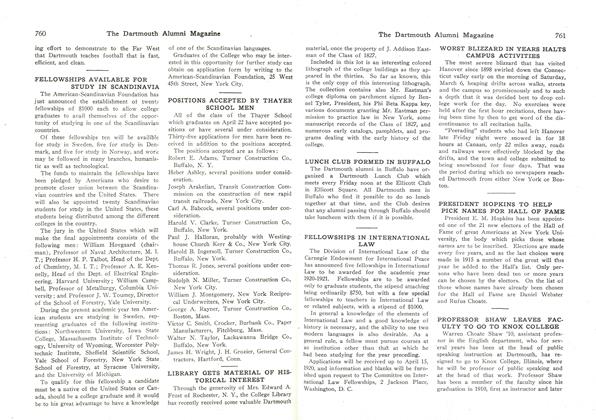

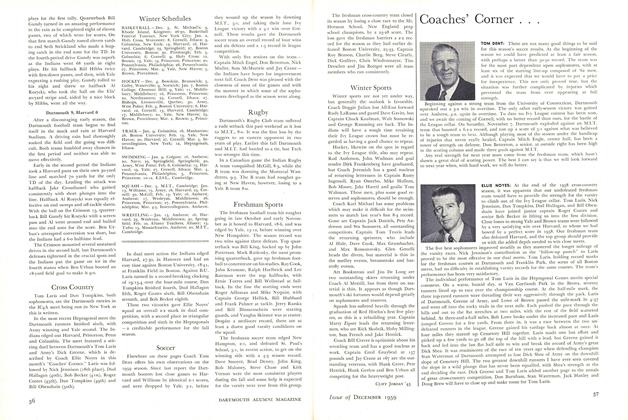

Charlie and Ing Mayo share in the pleasure their son Stormy (left) had in landing this 792-pound blue fin tuna.

Mayo at home is surrounded with signsof a lifelong, studious interest in the sea.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Fulbright Professor in France

November 1967 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26, -

Feature

FeatureMt. McKinley Conquered

November 1967 By Anthony H. Horan '61 -

Feature

FeatureFINAL REPORT 1966-1967

November 1967 By RALPH LAZARUS '35 -

Feature

FeatureTHE BETRAYAL OF IDEALISM

November 1967 -

Feature

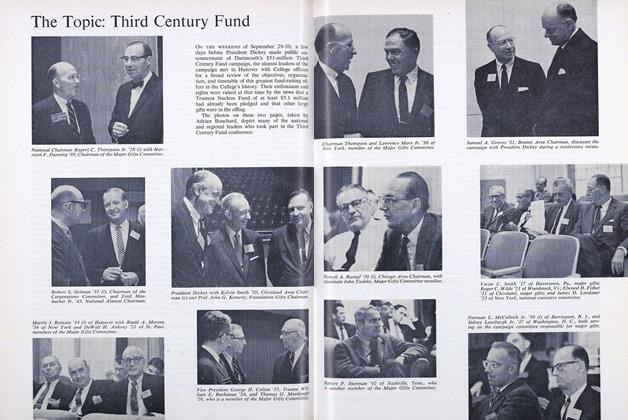

FeatureThe Topic: Third Century Fund

November 1967 -

Article

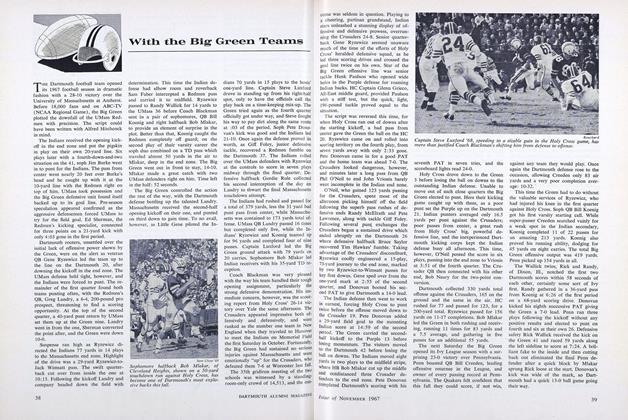

ArticleWith tine Big Green Teams

November 1967

CLIFF JORDAN '45

-

Sports

SportsBig Green Track Coach

January 1953 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticleWith Big Green Teams

January 1955 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticleRowing

May 1956 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleFootball

DECEMBER 1958 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleWinter Sports

December 1959 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleFootball

July 1960 By CLIFF JORDAN '45