THE STRUCTURE OF POLITICAL THOUGHT, A STUDY IN THE HISTORY OF POLITICAL IDEALS.

JULY 1968 VINCENT E. STARZINGERTHE STRUCTURE OF POLITICAL THOUGHT, A STUDY IN THE HISTORY OF POLITICAL IDEALS. VINCENT E. STARZINGER JULY 1968

ByCharles N. R. McCoy '32. New York:McGraw-Hill Company, Inc., 1963. 323pp. $5.95.

"Never before in history has life itself seemed so random a thing and existence so marginal and insecure." Father McCoy's essential argument is that we have reached this wasteland because the post-medieval western world has betrayed — first in philosophy and then in politics — the Aristotelian-Aquinian view of man and nature. By that view, man occupies "a center position between the condition of creator and the condition of nature" — a position from which human intellect can comprehend the moral ends of life and project those ends upon nature. That, in turn, gives man the possibility of freedom from both nature's blind necessity and manipulation by political charlatans. The author traces the betrayal of this classic view largely to what he calls theories of "autonomous natural law" which pervade modern liberalism, conservatism, and Marxism. By rejecting man's teleological moral purpose, these theories in effect reduce the human intellect to a mere datum of nature. Natural law itself becomes simply a description of nature, including the brute empirical behavior of man. With that, both natural law and modern political theory cease to be a standard by which society can identify or censure man's misbehavior.

This study illustrates dramatically how the history of political ideas, a subject too poorly regarded in political science of late, can help make some sense out of the world around us today. A problem of course is that the prescribed return to Aristotle and Aquinas cannot satisfy those, who are unable — for one reason or another — to accept the premise that there exists in the universe a "Prime Intellect by whose perfect freedom all things both are and are governed." One must accept that premise either with genuine conviction or not at all. To accept it pragmatically simply because the idea seems "useful" is surely to betray the premise itself — whether the terms of discourse are secular or theological. However, if rational argument is ever capable of turning the unconvinced toward genuine conviction, perhaps Father McCoy has made that kind of an argument. His style, his scholarship, his grounding in philosophy, and his overarching analysis are brilliant.

Mr. Starzinger is a member of the Department of Government, Dartmouth College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

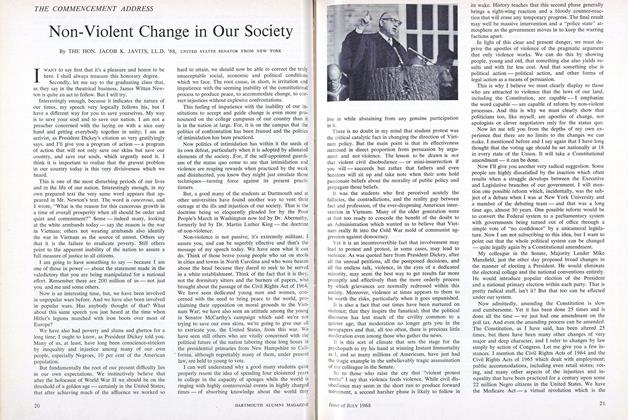

FeatureNon-Violent Change in Our Society

July 1968 By THE HON. JACOB K. JAVITS, LL.D. '68 -

Feature

Feature"People as Well as Things"

July 1968 By HARVEY P. HOOD '18 -

Feature

FeatureThe Senior Valedictory

July 1968 By JAMES WITTEN NEWTON '68 -

Feature

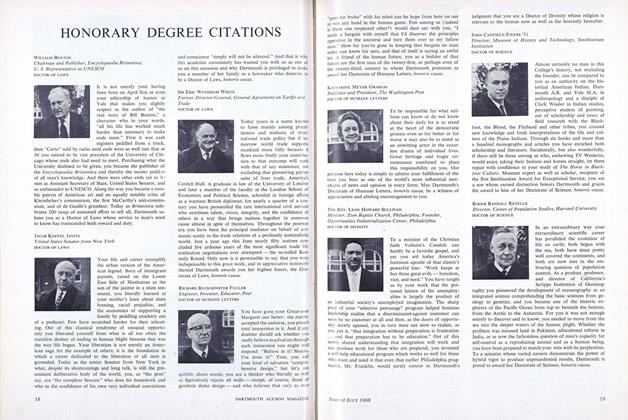

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1968 -

Feature

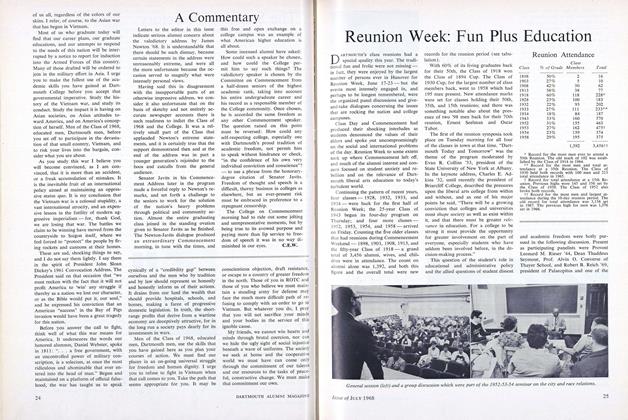

FeatureReunion Week: Fun Plus Education

July 1968 -

Feature

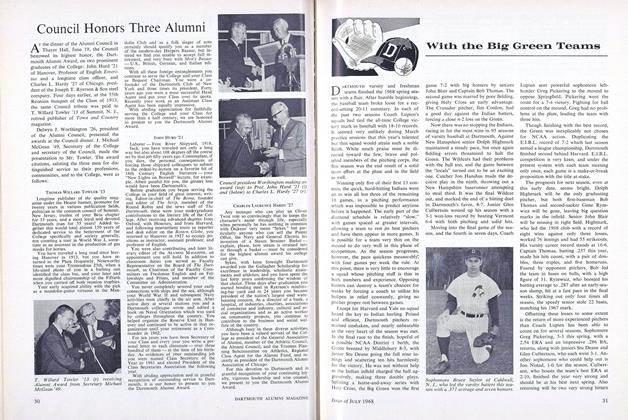

FeatureCouncil Honors Three Alumni

July 1968

VINCENT E. STARZINGER

Books

-

Books

BooksThe Country Newspaper: A Study of Socialization and Newspapaer Content

NOVEMBER, 1926 -

Books

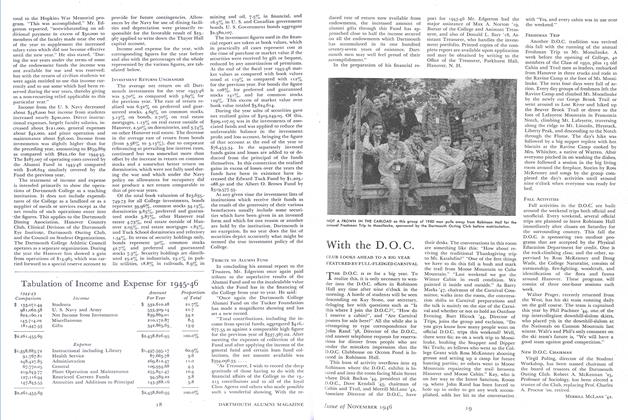

BooksProfessor Roy P. Forster

November 1946 -

Books

BooksPORTUGUESE AFRICA.

JANUARY 1968 By CHRISTIAN P. POTHOLM II -

Books

BooksAll the Clutter Gone

March 1975 By CLAUDE G. LIMAN '65 -

Books

BooksSIXTY DARTMOUTH POEMS.

MARCH 1970 By ROBERT H. SIEGEL -

Books

BooksLE CULTIVATEUR AMÉRICAIN

May 1933 By S. G. Patterson