Defining him precisely is one of the more hopeless tasks, but the author undertakes to alleviate the conservative's crisis of identity

True consensus, that will o' the wisp in human affairs, remained as elusive as ever during the latest spring brouhaha at Hanover. The evidence keeps surfacing in the June ALUMNI MAGAZINE commentaries on "great educational experience." Prof. James Davis speaks of that "delicate" issue—how to keep a shaky coalition of center, left, and far left from "coming apart." More specifically Masselli and Rockwell note the "running skirmish" between radicals and pragmatists over strike tactics; while the blacks, taking their cue from the fabled son of Peleus copped out on the whole affair and retired to brood in their tents.

If it is any comfort to them, consensus problems are scarcely monopolized by gentlemen of the center, left, and far left. Conservatives too have their fair share and these are by no means confined to relatively uncomplicated matters like strategy and tactics. To put it bluntly, conservatives suffer from a crisis of identity at least as severe as the more publicized problem among American blacks. What or who, precisely, is a conservative? Wrestle with this question in the nation's libraries or out in the hustings; the results are predictably the same. In lieu of precision and authority one is far more likely to uncover ambiguity and non-consensus. And yet—instinctively —one senses there is a creature, a mind, an inclination if you will, that can be called conservative. How, then, does one fathom it?

Popular types and stereotypes are revealing. F. A. Hayek in an essay entitled "Why I Am Not a Conservative" asserts that conservatives are generally identified by their resistance to drastic change. Unable or unwilling to offer alternatives to traditional social and political patterns, they fall back upon obstructionism. Visualize then the caricature of a stolid, pipe-smoking Tory, a bit thick in the head—considerably more so about the middle—sitting adamantly in the center of a path labeled "Progress," every jot and tittle of him proclaiming "They shall not pass." Biased? Of course! Incomplete? To be sure! But—effective propaganda and eminently acceptable to a host of liberal and radical activists.

Russell Kirk, the articulate conservative philosopher, labels a second type, the "shop and till" conservative. This fellow supports the status quo out of fear that radical political measures will destroy the material interests of property holders. His views have a certain directness that may be enshrined in a single dictum such as "Whosoever rocketh the ship of state slighteth the Dow Jones Averages and the mortgage market and is therefore thrice cursed." Let's face it. None of us is above self-interest. To the extent that we are

property owners we incline to those institutions favoring stability and tenure of property. Indeed a sound conservative case can be made that a free society is impossible if divorced from property tenure, but to accept the "shop and till" conservative as characteristic of the entire breed is to slander men like T. S. Eliot, Joseph Conrad, George Santayana; not to mention Winston Churchill and Federalists like John Adams and Alexander Hamilton. Again, the stereotype is far too limited to be helpful.

Many who read this may shortly have occasion to observe the third type. He is the Instant Conservative or the conservative born of fell circumstances rather than of sustained conviction. This gentleman is normally a live-and-let-live middle-of-the-roader, an educated man of modest pretensions who prides himself on his tolerance and his increasingly cosmopolitan outlook. He is concerned about the unrest he reads of in his newspaper and the violence he sees on TV. He is much too busy however with his job, his family, and his civic work to be unduly aroused. But—let the Black Power boys in his town mix it up with the police or let the Students for a Democratic Society occupy the local university and, wonder of wonders, our tolerant worthy suddenly becomes a tiger. Often to his own surprise he discovers himself shoulder to shoulder with the Birchers, the D.A.R., and the American Legion Post, clamoring for National Guard bayonets and no quarter to the rascals. The phenomenon of the abruptly polarized moderate waxes increasingly familiar in our American countryside.

Yet a fourth type is the Robert Welch or Paranoid Conservative. William Buckley aptly summarizes Welch's unique contribution to conservative thinking; namely, an Olympian conviction that the discerning observer "may reliably infer subjective motivation from objective results; e.g. if the West loses as much ground as demonstrably it has lost during the past fifteen years to the enemy, it can only be because those who made policy for the West were the enemy's agents." Such logic led Welch to assert unequivocally that the late Dwight D. Eisenhower was a dedicated Communist. The source of the classic rebuttal to this accusation is uncertain but one might conceivably attribute it to an obscure Republican matron who is reported to have protested indignantly, "Eisenhower is not a Communist—he's a golfer."

Buckley himself, premier apologist for the conservative cause and seldom averse to a measure of whimsy, cheerfully adds to the general confusion with the following statement:

... I have never failed to dissatisfy an audience that asks the meaning of conservatism ... (I) am deterred by the knowledge that conservatives, under the stress of our times, have had to invite all kinds of people into their ranks... and the natural courtesy of the conservative causes him to treat such people not as janissaries, but as equals... so (that) it becomes difficult to see behind the khaki, to know surely whether that is a conservative over there... or a radical, or merely a noisemaker, or pyrotechnician (for) our rag tag army sometimes moves together in surprising uniformity and there are exhilarating moments when everyone's eye is Right.l

So much for stereotypes and popular fantasies, and we have by no means exhausted the categories. The question persists. Can we reach beyond distortion, beyond caricature, beyond illusion, and grasp the essential quality of the conservative? More important still, having grasped what he is, can we test the validity of his insights? Perhaps not—to everyone's satisfaction; probably never in a brief article by a writer who has no special gift for prophecy. For conservatism in essence is a way of looking at the Social Order, what our psychologist friends in their distinctive jargon like to label a "cognitive structure." Having looked Song and hard at the community of man, the dedicated conservative is convinced that he—sees! He has no manifesto, no ideology or panacea for the salvation of mankind, no single political system to fasten upon Eskimo and Hottentot alike. To the contrary, he accepts the community of man as it is in all of its teeming diversity. He cries an everlasting Yea! to the sum of any nation's historical experience, its dominant religion, its ancient habits, its traditions, and its customs. Reader, mark these well!—experience, religion, tradition, habit, custom—they are conservative shibboleths not by chance but by deliberate choice. Why? Because in a notoriously fickle and veering world, a place where man's reach for the moon is exceeded only by his braying at the moon, these are time-tested and proved. They—stand.

From this base one can deduce a few principles, the makings of a conservative canon, as it were, which hopefully is both enlightening and consistent. Consider the principle of diversity, the frank acknowledgment that marked differences exist among men and among nations. To the conservative mind the notion that all men are created equal borders on apostasy. The Marxist ideal of a classless society enveloping the nation like a shoreless sea contradicts the evidence before his eyes every moment of his waking life. A fluid society where men rise and fall according to their natural merits, where men of equal worth in the eyes of God can hope for equal justice before the law—a resounding yes! But a society comprised of men of equal energy, equal talents, equal aspirations, and equal rewards—decidedly not.

In a similar vein the conservative who holds his own customs and traditions to be of great value tends to respect the customs and traditions of other nations. A Congregationalist magistrate from Vermont will not embrace the Catholic Mass of a Spaniard from Castile. Nevertheless he respects the Mass as right and proper for Castilians on Spanish soil. While both Vermonter and Castilian would find it personally distasteful to eat the body of an enemy killed in battle, each instinctively recognizes the validity of this ancient practice in terms of ritual, a ritual designed to maintain social unity and authority among certain tribes of, let us say, the Upper Congo. As conservatives, neither Vermonter nor Castilian would wish to assert that his particular ethical system is better suited to Congo environment and social conditions than the pattern that has gradually evolved there after centuries of trial and error. One does not lightly meddle with patterns imposed by Providence. A second principle is the conservative's tendency to look to the past for guidance. The human race, he observes, has been around for a long, long time and he finds the record of this sojourn to be both meaningful and authoritative. Most significant is history's stark witness that despite the rise and fall of civilizations, the vast accretions to human knowledge, and the competing claims of numerous ideologies, fundamental human nature has changed very little during the past three thousand years. Nor is it likely, he believes, to change very much in years to come. Contrary to all liberal tenets, he concludes that what ultimately moves men and nations is not what we know, not what we aspire to be, but what we are. And in perspective, what we are frequently does not make pleasant reading. Does one question whether factionalism and clashing self-interest can destroy a democratic nation: Read how they brought down the city-state of Athens in the 5th century B.C. Would you learn how to govern restless minorities? Read how the Romans for 400 years practiced this art successfully in the ancient Mediterranean world. Do you desire a lesson in political tactics for troubled times? Look through the pages of The Prince by Niccolo Machiavelli, a 16th century Florentine whose little treatise has been studied by aspiring politicians and dictators for over 300 years.

Small wonder the conservative considers a study of history to be indispensable to the educated man. And small wonder that conservatives tend to distrust innovators and reformers, "especially radical reformers who offer quick nostrums for human order, justice and freedom"; who would "hack and tear at established customs and institutions in order to remold society to their own liking." The conservative holds that human society is a "complex organism," that remedies for its ills cannot be simple if they are to be effective, and that "the misplaced ardor and hurried reforms of liberals more often than not bring abuses which are worse than the evils which they attack." Above all, the conservative is aware that order, justice, and freedom, far from being "natural rights," are instead "artificial products of long and painful experience" and that men are most unlikely to discover anything new in the realms of either morals or politics.2

Yet a third principle in the conservative canon is open to some dispute, but the lack of consensus has occurred relatively recently. For more than two millenia a majority of conservatives have adhered to the notion that the Society of Mankind is controlled by Divine purpose; and that this purpose, however dimly discerned, is constantly at work in human affairs. Human life, they feel, far from being a "senseless dance of atoms" in which men are trapped and dominated by forces beyond their control, is instead meaningful; meaningful even though the ultimate meaning continually "transcends the observable facts of existence." Political and social problems, the conservative is convinced, are fundamentally religious and moral problems. Eliminate religion and you eliminate morals. To a skeptical generation offended by the superficial moralizing and the blatant hypocrisy so prevalent in our society he points out that moral order imposed from within is the sole alternative to a secular order imposed from without. "How so?" cries the indignant liberal. Let the reader reflect for a moment. What authority remains constant in our society where all is flux?3 Public opinion? It ebbs and flows like the tide. The Law? It changes from day to day. The Constitution? An abused instrument manipulated by nine fallible men in Washington. Remove the internal restraints of religious faith and there remains little more than self-interest. And to what end does naked self-interest, the cult of Number One, lead? In a democracy beset by the recurrent crises of our times factionalism intensifies and civil disorder becomes endemic. Force and coercion, initially employed to stem the tide of social dissolution, quickly evolve into a way of life. For the sake of order constitutional guarantees are first suspended. Soon enough they are forgotten. Men then submit to a master, to the secret police, to the torture chamber, and live out their lives miserably under a pall of fear. Such is the classic pattern with which we are threatened in this country where our citizens have largely abandoned their faith for the transient mirages of moral freedom and the myth of human perfectibility.

Here let us pause to consider a fourth principle in the Conservative Canon; one that concerns the nature of man, or as theologians like to call it, the human condition. We have already mentioned the conservative thesis that what ultimately moves men is what we essentially are as human beings, not what we know or hope to be. Liberals have traditionally disputed this position. Ever since the 17th century Enlightenment they have insisted that man is a rational creature living in a rational universe, that human evil far from being a complex moral problem is largely a matter of irrational behavior, that "bad" men are the logical end products of bad experience, bad environment, bad institutions, and bad training. Discarding both the lessons of history and the insights of his traditional faith, the liberal places all his bets on the future. He hitches his wagon to a star called "progress" by means of which men, constantly improving their environment with the aid of science, universal education and positive legislation, become a bit more like God with every passing generation until the problem of human evil finally vanishes altogether in a society that is at last completely rational. Such a description of the liberal position may be slightly overstated—but not by much, really.

The conservative takes a dim view of this argument. After contemplating the three centuries that have elapsed since the Enlightenment he finds the liberal's optimism to be unsupported by the historical facts. During the 20th century alone he has witnessed in the Western world two major world wars, an endless string of coups, a major depression, and the fine art of genocide perfected to a point where six million helpless civilians could be exterminated by a presumably civilized and "enlightened" nation.

And what of America-technologically supreme, better fed, better housed, and better educated than ever before? For much of the past 35 years Administration and Congress alike have attempted to restructure the nation by grinding out reams of liberal social and economic legislation under euphoric titles like the New Deal, the Fair Deal, the New Frontier, and the late Great Society. "New" and "Fair" indeed! The visible results of this frenetic activity again fail to confirm the liberal's thesis. Sorely beset by inflation, we fight a debilitating war in a distant land, our cities rot and riot, our environment literally stinks, our crime rate soars, and the two races confront each other while men on both sides mutter darkly about a coming Armageddon. Worse still, fear, confusion, and distrust like "dank effusions from some miasmal swamp" sift into every cranny of the land, subtly poisoning men's relations with one another.

Unlike the frustrated liberal who sees his case for human progress vanish into the polluted air and wonders what went wrong, the conservative is not surprised. Liberals have failed because their basic premises are wrong. For the conservative, progress in human affairs is at best qualified and highly tentative while the entire notion of human perfectibility is a tragic illusion. His pessimism inclines him to view human nature as essentially and irretrievably flawed. Men may pay lip service to the virtues of human reason but in practice they use such reason as they possess not in the cause of human progress but primarily to advance and then to justify, to rationalize their own ambition and self-interest. If left to their natural inclinations, the majority of ambitious men drive not for human progress and perfectibility but for wealth and power and a host of even less attractive vices. Call it human sin if you are religious—human perversity if you are secular; the fact remains that human evil is compounded of a good deal more than the simple imperfections that spring from a bad environment. Indeed the trouble lies wholly within men's passionate hearts and few conservatives worthy of the name will disagree with the Orthodox Christian insight expressed by Reinhold Niebuhr:

The order of human existence is too imperiled by chaos, the goodness of man too corrupted by sin, the possibilities of man too obscured by natural handicaps to make human order, human virtue, human possibilities solid bases of progress.4

Accepting this bleak assessment of the human condition and the historical reality of a dangerous and violent world, the conservative statesman eschews radical Utopias for the more practical mission of reducing "the anarchy of the world to some kind of mmediately sufferable order and unity." He has few illusions about his own or anyone else's ability to improve society by social engineering, preferring wherever possible to build on local institutions, local customs, and local traditions. If he has a libertarian bias he seeks to strike a balance, constantly weighing "How much authority? — How much freedom?" What form of government will be strong enough to protect society from the greed, ambition, and acquisitiveness of its own members and still be able to resist its (the government's) own appetite for ever-increas- ing domination and control. One hundred and eighty years ago James Madison stated the problem quite succinctly. "In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men," he wrote, "the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed and in the next place oblige it to control itself." In Federalist Paper No. 10 Madison further observes that in a free society where men are left to pursue their own interests, factionalism is inevitable, that since it cannot be eliminated it should be controlled by the legislature. He warned, however, that democratically elected legislators would frequently be partisan to the very conflicts they would be called upon to mediate. Obviously conflict-of-interest problems in government were recognized from the very beginning.

Fortunately for America, the framers of our Constitution were conservative men of extraordinary caliber. Madison, James Wilson, John Adams, Gouverneur Morris, all of them knew their country and their history well. Their carefully contrived system of checks and balances is as remarkable a testimonial to their insights into human nature as it is to their skill as practical statesmen. Power centers throughout the system are ingeniously dispersed. The division of authority between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the Federal government reduces the likelihood that any single branch will arrogate complete power unto itself; and yet the central government remains sufficiently strong to maintain order and dispense justice while carrying on routine business. Similarly, local government, local customs, and local institutions are protected from Federal infringement by Article X which stipulates that all powers not specifically delegated to the Federal Government or prohibited to the states "are reserved to the states respectively or to the people." The potentially disruptive force of factionalism is inhibited by a relatively simple tactic—that of encouraging the largest number of factions practicable from the widest possible geographic area to be adequately represented so that no single faction can utterly dominate the Congress. Building carefully upon Anglo-American political and social traditions, these conservative men created a political instrument that has worked as the fundamental law of a dynamic people for six generations. It more than any other American institution has helped us to remain free from the revolutions, the tyrannies, and the radical collectivism that fret and churn so much of the civilized world.

There is more, much more, but limits of space and reader patience suggest we had best summarize what we have said so far. What is a conservative? At times a man who walks beneath the stars in silent wonder at the mystery of this diverse creation into which we are born without our consent and from which we depart against our will; always a man who regards his fellows not as faceless ciphers of the collective state but as "individuals whose capacities, interests and needs are characterized by rich and changing variety"; a man who views the customs, the traditions, and the institutions of his native land as the handiwork of a Providence that works in and through men. As a conservative he strives to reconcile the best in the old order to changing social conditions while he instinctively distrusts radical innovators whom he considers "... to be obsessed with change itself, to be lacking in historical perspective, and prone to substitute expediency for sound judgment and experience." He considers the record of history to be man's greatest teacher, the divine law and the will of Providence to be his ultimate guide, and the perversity of human nature to be a cardinal consideration in any successful political system erected by men.

We might also point out that he generally marries, raises a family, pays taxes, and after a prosaic career descends to the grave considering himself fortunate indeed if he has earned the respect and affection of his peers and somehow managed to stave off the "... chaos and meaninglessness which [have] beset the human spirit throughout the ages." In short, he is not unlike other men.

NORMAN LAZARE '40 resides in Pembroke, Kentucky, where he operates the 670-acre Runnymede Farm, on which tobacco and livestock are raised. His article defining the Conservative's credo has been reworked from a paper he gave before the Athenaeum Society of Hopkinsville. Holder of the M.A. in English, Mr. Lazare also teaches at Austin Peay State College in Clarksville, Tenn. The basic ideas in his article have been known to the Western World since the days of Edmund Burke, he says, and his aim here has been "the selection, arrangement, and burnishing of these few old notions in a way that renders them meaningful to contemporary eyes and ears." Mr. Lazare's son Lewis is a Dartmouth freshman.

1 William F. Buckley, "Notes Towards an Empirical Definition of Conservatism," What is Conservatism, edited by Frank S. Meyer, (New York 1964), pp. 218-219

2 Restatements of traditional views held in common by British and American con- servatives. 3 A question raised by Alexis de Toque- ville in Democracy in America.

4 Reinhold Niebuhr, An Interpretation ofChristian Ethics, Meridian Books (New York 1958), pp. 53-54.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOpportunities for the Coming Year

November 1970 -

Feature

FeatureThe Boom in Off-Campus Study

November 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

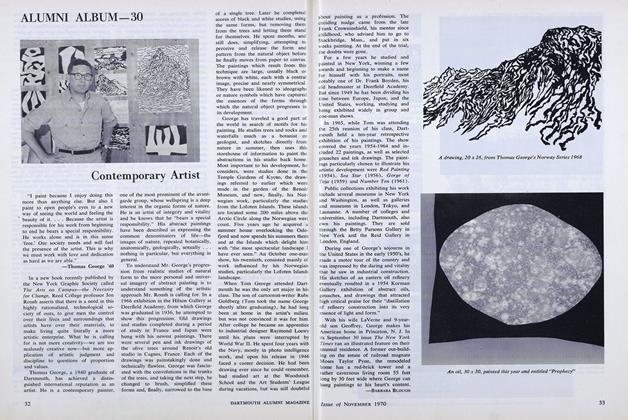

FeatureALUMNI ALBUM-30

November 1970 By —BARBARA BLOUGH -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1970 -

Article

ArticleThe ROTC Decision: An Explanation

November 1970 By ARTHUR LUEHRMANN -

Article

ArticlePresident Kemeny to President Nixon...

November 1970 By John G. Kemeny

Features

-

Feature

FeatureIn sum:

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureThe Administration

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureSon of Animal House

SEPTEMBER 1989 By Ed. -

Feature

FeatureEducation the Groove

March 1957 By RAYMOND J. BUCK JR. '52 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May/June 2012 By SPORTING NEWS VIA GETTY IMAGES -

Feature

FeatureThe Black Student at Dartmouth

JUNE 1968 By Wally Ford '70