A World of Difference

Revolutionary advances in geography (can you say satellites?) have transformed the field and how it is taught in the only dedicated geo department in the Ivy League.

May/June 2009 CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS’04Revolutionary advances in geography (can you say satellites?) have transformed the field and how it is taught in the only dedicated geo department in the Ivy League.

May/June 2009 CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS’04REVOLUTIONARY ADVANCES IN GEOGRAPHY (CAN YOU SAY SATELLITES?) have tRansfoRmed the field and how IT IS TAUGHT IN THE ONLY DEDICATED GEO DEPARTMENT IN THE IVY LEAGUE.

Although the stuDy of geogrAphy

among the ivies has a long and illustrious history dating back to colonial days, Dartmouth is currently the only one with an independent geography department. Last June 48 majors graduated, an increase of almost 100 percent from the previous year.

“geography has a new street cred in the academy, more so than it did 20 years ago,” says department chair richard Wright. “We see people reading us and turning to us more intently now.”

Just ask some geography majors.

“i was drawn to the department because i didn’t feel constrained by the subject,” says elsa Sargent ’08, who is now working with the Cascade land Conservancy in Seattle. “it’s one of the few departments that offers such a cross-disciplinary study, allowing you to focus on anything from international development to physical processes while also letting you explore the expanse and diversity of the field. that’s really important to me in a liberal arts education. it also has the most supportive and fun professors who are focused on the undergraduate student as much as their personal research.”

eric Cates ’08, who worked for the Wisconsin office of Energy Independence after graduation and is now explor- ing career options in international agricultural development while coaching skiing, sees geography as a mix between cultural studies and political studies. “i like that there is a wide range of focus within the department, including human, political and environmental studies,” he says.

the department reflects the fact that geography has gone from the study of “where” to being a complex, interdisciplinary field that addresses some of the most serious issues of our times. Areas of specialization among the 10-person faculty range from geoarchaeology to immigration, race, feminism and science—to mention only a few.

The department has long been interdisciplinary. In the 1950s and 1960s professor David Lindgren co-taught courses with sociology, history and government professors. Two of the geography department’s current faculty—Jennifer fluri and Chris Sneddon-hold joint appointments with the women’s and gender studies department and environmental studies, respectively.

dartmouth’s department has remained intact in large part because of the faculty’s success at riding the waves of change in the field. The wide-ranging topics reflected in faculty specialties inform geography and, in turn, geography’s spatial perspective offers a unique—and crucial—analytical tool.

“historians look at events through time. geographers can look at anything through space,” says emeritus professor george Demko, a former director of the Office of the Geographer of the United States with the State department. “this unique spatial outlook is in increasing demand in other disciplines.”

“We get involved with everything,” says Wright. “you need to understand spatial relations to understand society. Think about important contemporary issues. you need to understand iraq’s geography and history in order to understand the complexity of the current situation there.”

Much of the creDit for the vitAlity of

the department goes to the late robert huke ’48, a muchbeloved professor who joined the faculty in 1953 and energetically promoted the department across campus. He did so at a time when the field struggled nationwide with a reputation for offering “gut courses,” a problem exacerbated by a 1963 Time article on “easy a’s” that ridiculed a yale geography course with no required reading.

For much of its history the department, like the field, was centered on physical geography, which emphasizes the study of the earth itself, rather than the impact of people on the earth and vice versa. Up to the 19th century—and even into the mid-20th— most geographers were largely concerned with exploring new worlds and mapping what they found.

“Cartography has been part of geography since time immemorial. the early greek geographers were all measurers,” says Demko.

in keeping with the country’s fascination with exploration (as evidenced by National Geographic’s popularity at the time), scientists declared 1957 the Geophysical Year. Geographers devoted 18 months to researching that which had been previously unexplored in the physical world. At the end of that time most of the world had been mapped, and the advent of the satellite era eventually made the most remote parts of the earth more accessible.

In 1966 another technical advance hit the field of geography. Harvard provided the facilities for the Laboratory for Computer Graphics and Spatial Analysis, which developed prototype computerized mapping systems. These early programs progressed into GIS (geographic information systems), which has had a profound impact on geography. Combined in 1972 with the Earth Resources Technology Satellite, which became the LandSat system, information that had been confined to military uses hit the public domain. These systems now are routinely used by travelers charting trips across town or across countries.

The field has come full circle to the early Greek geographers, says demko, who calls giS a “whoppingly” important field. “We’ve come back to measuring the earth with a vengeance, because cartography has become giS,” he says.

Aside from the GIS programs that enjoy both attention from the press and popular use—Google Earth and MapQuest, for example—on a scientific level GIS has created a quantitative revolution in geography that has transformed both the physical and human sides of the field.

For professor Xun Shi, whose area of concentration is quantitative spatial analysis—a field that sounds drier than it is—GIS is an essential tool in a collaborative project with Dr. Eric Buell and Dr. Ethan Burke at the Medical School. Together they are examining the distribution of lung cancer in New Hampshire in a five- year project for the National Institutes of Health.

“We’re looking at the same project from different perspectives,” say Shi. “they are epidemiologists and i’m a spatial analyst. Examining the spatial patterns of lung cancer allows me to see if some areas have abnormally high incidences and, if so, if they are associated with environmental factors such as heavy metals or air pollution. traditional epidemiology doesn’t have such a strong spatial perspective.”

The new quantitative tools enable geographers not only to bring advanced statistical analysis to the field but also to marry the human and physical sides of geography in innovative and fruitful ways. As both a natural science and a social science, geography brings a spatial perspective to pressing human issues, exploring the movement through space of people, money, pollution, disease and political ideology, among myriad other issues.

While the 1970s brought a strong environmental emphasis to geography, the 1980s brought another question to the field of human geography. A series of articles by both male and female geographers asked, “Where are the women?”

The study of human interaction with the earth, up to that point, had focused almost exclusively on men. The feminist revolution in the field led to the inclusion of women in research topics—population trends or mobility issues, for example—and to an examination of how various geopolitical issues are affected by gender.

“home is a geographic space, one that is architecturally structured based on gender norms,” says fluri, a member of the department since 2005 and a specialist in feminist geopolitics in afghanistan. “for example, homes in the islamic world have no exterior windows, so women can’t be seen from the street, and contain instead interior courtyards for privacy.”

Her current work considers how relief agencies focusing on women in afghanistan can work more effectively. “they’re banging their heads against walls,” she says, “trying to figure out how they can create change for women. Efforts up to this point have largely failed.”

Fluri has found that aid projects whose personnel have a personal, trust-based relationship with Afghani women fare better, a human connection profoundly affected by spatial issues. Aid workers in Kabul often live inside compounds surrounded by barbwire that afghans aren’t allowed to enter. Some aid workers, to their intense frustration, aren’t even allowed to leave these compounds.

“i’ve interviewed people on both sides of the fence,” says fluri. “Because of my geographic training i always think spatially and ask myself, ‘What are the spatial barriers—physical and metaphysical—to economic, social and political change?’”

DArtMouth’s geogrAphy DepArtMent

has always emphasized undergraduate teaching and actively encourages and participates in collaborative research projects between faculty and students.

as an example, tina Catania ’03, who now works as a research and teaching assistant in the department, studied racial identification for Latinos with Wright, using GIS and census data to map the ways space and race affect each other. “different places produce different understandings of racial identity,” she says. When races congregate geographically, they tend to identify and be identified in terms of their race rather than by other factors. “identities,” says Catania, “are performed,” meaning they shift in relationship to different groups.

Serin houston ’00 also worked with Wright researching identity performance in the Tibetan diaspora after traveling to India and Nepal to interview Tibetan refugees. As her advisor, Wright suggested she try to publish her research. Together they revised one aspect of her thesis and co-authored an article that was subsequently published in the Journal of Social and Cultural Geography.

Later they collaborated on two journal articles about racial mixing. “Working with richard was probably one of the most exciting and dynamic aspects of my undergrad experience,” says Houston.

She went on to earn her master’s in geography at the University of Washington and is a visiting assistant professor at Dartmouth while pursuing a doctorate at Syracuse University. She is studying urban place making using an urban feminist perspective.

Catania and Houston are among many majors who continue to pursue geography in academic settings. peter nelson ’93 wrote his senior thesis on rural commuting in the Upper Valley and now studies rural and urban migration as a professor at Middlebury. “for me it’s fascinating to see how groups of affluent people can so dramatically transform the rural places in which they land,” says nelson. “there are perhaps no better places to see this than in the Upper Valley around Dartmouth or in the Champlain Valley here at middlebury.”

for Jay Samek ’87 a postgraduate summer spent extracting tree core samples on Mount Moosilauke with professor Laura Conkey—as part of a project mapping acid rain and forest decline— foreshadowed his work as a research scientist at Michigan State University. There he uses remote sensing satellite imagery and GIS to map land-cover changes that impact global climate change. “global climate change and poverty, arguably, are today’s most pressing problems,” he says. “geographers are uniquely positioned to help find solutions.”

With his colleagues from MSU, Samek hopes to assist farmers in developing countries to register with emerging carbon markets any lands that are being reforested or are in agroforestry management systems, addressing both environmental issues and poverty at the same time.

“geography makes you think about the situations we face now and what we can take from past experiences to better ourselves and everyone else in the future,” says recent graduate Cates.

“i chose the department because of its size,” says anna payne ’08 of her decision to focus on geography. “it felt more intimate than some of the others I was considering for a major. I was really able to talk to and get to know some of my professors; they do a good job of integrating their research interests into their classes.” Payne now works on Capitol Hill.

“Students come to dartmouth for a liberal arts education,” says Wright. “they come for close relationships with professors and relatively small classes. Our courses span humanities, social sciences and science, and we have students coming through other departments who decide that they can get everything they came for at dartmouth in geography.”

Catherine Faurot is a freelance writer. She lives in western New

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

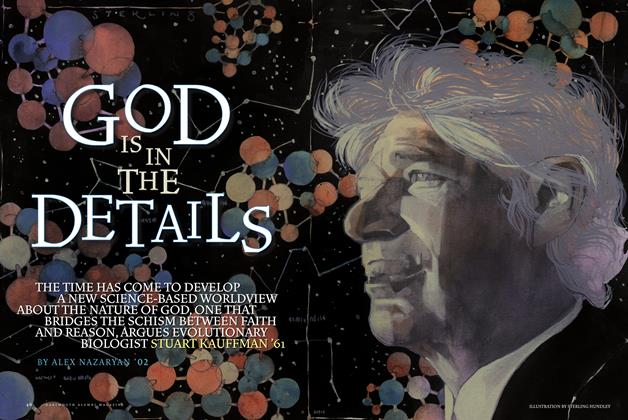

FeatureGod Is in the Details

May | June 2009 By ALEX NAZARYAN ’02 -

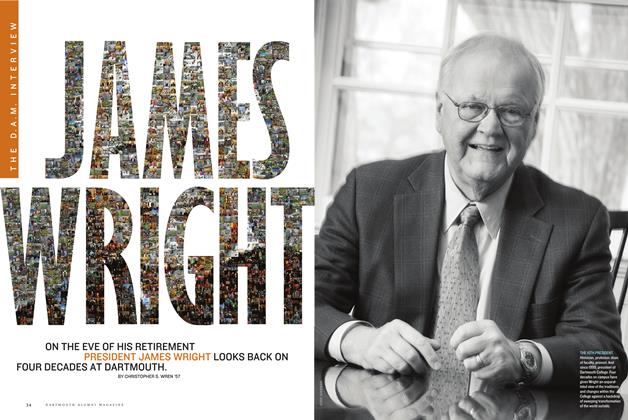

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWJames Wright

May | June 2009 By CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWalls That Talk

May | June 2009 By Judith Hertog -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2009 By BONNIE BARBER -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONSlow Medicine

May | June 2009 By Dennis McCullough, M.D. -

SPORTS

SPORTSIn a League of His Own

May | June 2009 By Brad Parks ’96

Features

-

Feature

FeatureWHAT OF ADMISSIONS AT DARTMOUTH?

October 1961 -

Feature

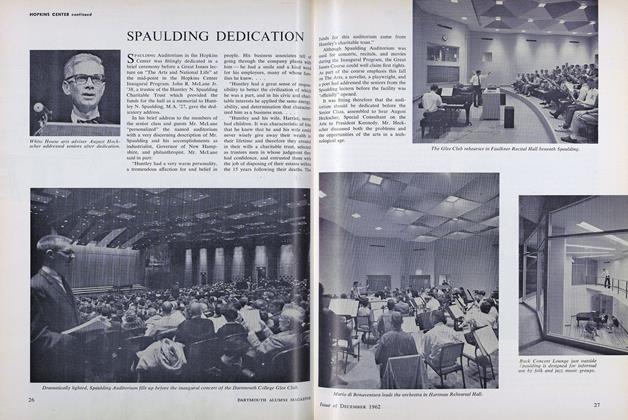

FeatureSPAULDING DEDICATION

DECEMBER 1962 -

FEATURE

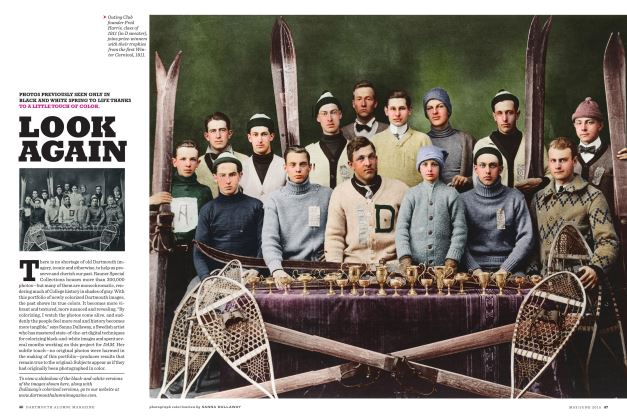

FEATURELook Again

MAY | JUNE -

Feature

FeatureStudents and Commitment in the Deep South

JUNE 1965 By BERNARD E. SEGAL '55 -

Feature

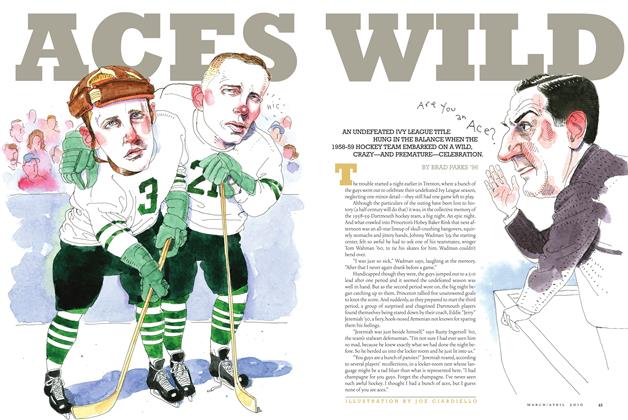

FeatureAces Wild

Mar/Apr 2010 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham