James Olstad, a senior, wrote this for Prof. Noel Perrin'sEnglish 40 last term. Professor Perrin, who gave him a citationfor the term's work, commented: "I think him to be one of thetwo writers I have had in the past five years who may make amark in the outside world."

Reflections on a large theme are always influenced by mood.

And those statements posited, grandiose and subtle philosophies that unwind, become different things in different lights: idea in the morning is imbecility at night.

And the negative mood is produced of, and produces, negative image.

And one thought follows another, as footsteps bedded in a path; a spiral downward; achieving murk or depression and despair. Insight feeding upon impressed light, and birthing a different dilemma for each day.

The Philosopher is a different man, and the Novelist, his younger brother . . .

Derelict sailors:

old men of ulcerated sores and stubble beards, heavy with scents of body oil and windspun salt air. Drinking cheap gin and rum and rye in tiny canteen bars along the waterfront. One of their number, a proprietor. Who orchestrates their conversations, and serves as anchor to wandering sets of minds. Swaying thought and body motions propped against the bar. Recalling how it was before, so as to not remember now. Down and out in Norfolk. Virginian mother of the Founding Fathers. Foundlings. Bothers and blights of some child's memory that did not become what it wanted to be ...

A Nobel Prize winner:

who lived his entire life to produce one equation, and who is remembered always in some remote encyclopedic listing, preceded by a date, and appropriately captioned-below and labeledabove. Known also to a small coterie of friends and professional acquaintances. Remembered for one item or another of personality or being. Just as the old sailor who sits in the corner and says Nothing to No One is remembered for a fact. He Never Spoke A Word.

One time, he must have. For when he appeared in the doorway, cold afternoons during the winter, Emanuel, the bartender, poured a coffee cup of whiskey and walked it slowly to his table. So as to never spill a drop and leave a whiskey-water mark that said, however tacitly, The Philosopher Has Been Here.

The Philosopher reached for change in his pocket, paid his bill, and began listening to a raucous world building and sprinkled about him. Not of him or around him, but in an atmosphere within, of which he was apart a part. Weird noise, eerie sight; strange and private thought to contemplate when other men would celebrate, and slap each other's backs and shoulders, and other portions of the room. Rough camaraderie enhanced by drinks of past and present as each man relived one or many of a store of tales, gab as gifts, a sharing of a lifetime's wealth. Then listened, and would nod assent as tokens of their time well spent, that "yes, that was true" and "certainly, it was so" and "which ship's berth have you now, might I ask?"

The Philosopher was sailing in the Emanuel. It left port every day at eight in the morning, whiskey destinations of varying distance. The bartender-owner hove into view outside the door, looked up at the sign that bore his name, and pulled one plain, unchained key from his pocket. Occasional coins and trouser lint sometimes mingled with it, confusing him for a moment in the just awakened light. Then he inserted the lock, or locked into an insertion, and twisting his device, appointed his way in. The door swung on its hinges, and the ship became motion.

Stewy arrived a few or many or sometimes-not-at-all minutes later. Emanuel was captain, and Stewy was his crew. Crew-duty was to sweep away the residue or yesterday; straighten the remnants of day-ago cargo, erase the mementos of previous fares. Bernie: who carefully placed a coffee can on the floor near his feet, and who was forever aiming streams of tobacco spit at a target that he never hit. Art: who crushed cigarettes into oblivion on the bar's surface. Other customers who snuffed theirs or emptied pipes at whatever point was nearest at hand and most convenient. Stewy was a busied man for his first half hour. Full of purpose pushing his broom, maneuvering chairs, asking early arrivers to move their feet. "Will you shove over there a bit, mate?" he'd ask, and continue through and past them. The Emanuel sailed quickly, and passengers were prompt as fate: never too early, never too late. Each boarding at a time coincident with time he should be there. That time often conflicting with the most efficient accomplishment of the new morning's tasks. Stewy, though, did not complain, did not register even silent protest with gods above or below. Stewy was a stoic, and it mattered very little to him how things were; he would endure. Time was whittled by each, motion of his broom, and he soon joined those men in the Emanuel bar whose morning pace was much more leisured.

Older men, and regular clients. Retired from the sea. Living on pensions, in boarding houses and small hotels near the docks. One-room quarters at weekly rates. With spartan, 1930's furnishings of a cot or bed, a table and chair, a closet and a seaman's trunk. Personal articles with storied pasts posted neatly and discreet around their rooms.

Bernie was a regular, the earliest of each morning's arrivals. A man in his seventies, who did not want to die on the first of the month if his rent was paid through the last. Weekly rates, once devised in suspicion of his and fellow's character, had evolved, were now conceived as mutual. protection. Landlords were assured their rents, and boarders reasonably certain of well spent money. Bernie repeated many times, at some point along a mock-morbid conversation, that he planned to pass on just after waking of the day rent was due. He wanted the satisfaction of having been consciously alive, for free, on that Friday. He wanted death to come just moments after he had risen to come to Emanuel's. Just minutes before he would have paid the next week's rent. He didn't begrudge the money. But he had no wish to pay for something he would not be able to use. Certainly, that was so.

Those were his thoughts on the matter. That is what he d said. And something he did not mention, something no one in Emanuel's would have suspected: the spittoon he had at his rooming house was a porcelain chamberpot from Holland, given him by a Flemish girlfriend of long, long ago. He never once missed as he unloaded over it.

The Novelist knew this, knew it was true. And because he is a younger brother, and more vocal, mentions it as an interesting fact.

The Philosopher knew that Bernie had stolen it. But would not give any details, did not think upon the matter further. The Philosopher's dilemma today was not the dichotomy of item or idea, nor necessary misrepresentation as practiced by general or specific men. He would confine himself, instead, to the influence of mood on idea, of temperament on theme. And also, it was a cold day, and the Philosopher had just sat down, was just beginning to warm himself a bit by taking tiny sips of his cup.

During the spring and summer months he rarely made an appearance at Emanuel's. Preferring, instead, to do his contemplating as he walked aimless along the quay. Watching ships fill, and unloading. Marveling still at the size, the hugeness and heaviness of monster-steel constructions floating on water; bubble and liquid pressing upon each other. Noticing how prows loomed over him, forcing his head back-and-back and back farther still as he craned to read a ship's name and see faces, not unlike his own, moving along the ship's deck. And think for an instant on rivets that had broken loose, on rust that was in endless feast on discolored, old ship-skin. Those objects, things, processes as silent in their work as he. But not subject to mood, insight, or impression as they pressed inexorably forward with their tasks. Their functions and resultants were not victims of capricious influence. Be it rain or shine, night or day, it was only fate and nature that held sway. And changes, though they did occur, were imperceptible to small. While mood was a more random phenomenon, and so, not even as imprecisely pin-able as fate or nature. And the random, as it was, it wavered through shorter spans of time. Sporadic, eccentric moments of greater, more marked consequence. What was crystal in the morning was muddled by the afternoon was unusable at night. So required a different day, as acquired a new dilemma, for and of the same old thought.

In the summertime, when it was warm and he was walking, he anil his (Formulations were different than those indulged in now. The Philosopher recognized this as he sat, quite still, and let the whiskey loosen chill bound inside his body. Warming, as he did, from inside to out, he thought of himself momentarily as antireptile in spring, and he began to wake, to focus on things aboutaround him in the room; and tried to perceive his perceiver's mood as he interpreted what was there.

It was early afternoon and gray light moved by rheostat to peak illumination. Two large, square windows on either side of the door admitted unwashed light from the street. Stewy's early morning attentions were confined to the floor, the table tops, and the shelves of bottles behind the counter. The only cleaning the windows received was wind and rain that brushed, in moments of turbulence, the outside faces of the glass. Inside, the accumulation of dust and grime continued, and light that penetrated was demoralized before fractionally entering the room.

To what extent this atmosphere created mood and channeled thought was never known, was left indeterminate and unresolved. Few men, either within or without Emanuel's, are conscious of the subtle shaping a concrete world has on their abstractions. And though the Philosopher noted the dimmed light, he was not a scientist, he could not gauge so many photons less, or odors more, and so did not venture an opinion or estimate of their effects. He only observed, then let the thought pass, unrecorded.

A group of younger men had entered the bar, strangers among a regular crowd, but friends between themselves. Sailors on liberty, Navy uniforms in a new port, strange city. They waited their appearance for the afternoon because they were still young, boys really. Because they were not yet so addicted to the life they led as to really need the company and comfort of early morning liquor. Because they had celebrated long into the preceding night as is customary, as is traditional, as may be necessary for men recently at sea. Without the company of women. With only interminable routine and open, empty, wide expanse of gray-on-gray-on-blue stretching endlessly around them: the Always-Always they sought to wash away, rinse themselves of, as they drank and copulated life and existence closer; something as real and pounding as a headache in the morning, or gentle, as a woman's touch. They were tardy because they wanted moments more inside their partner's body, and because they relished sleep to ease their hangovers away.

They made their appearance now, however, because it was a new day with its different dilemma; only 38 hours left before they put to sea again. Another round of life was called for, infusions for their systems; making the passage of time a less burdensome thing to bear. Emanuel served them, and Art immediately struck up a conversation by asking for a cigarette, and then a light. Bernie was busy by his coffee can in another part of the room, Stewy roused to give them only a passing glance, and the Philosopher watched and listened and made of them a mechanism, a trigger to provoke his thought still farther.

One spoke with a coarse seaman's tongue and attitude on events of the night before. Art guffawed appreciatively, and Emanuel detailed a history of one of the girls in question. The first seaman didn't believe the statements, especially the last, but would check with the ship's medic anyway. And the Philosopher remembered his own image as a man in his late twenties, his face stuck in a hotel room mirror in the midst of some masturbatory urgency. An unremembered city after a meandering and unsuccessful search. A companionless first night in port.

It was then, and in that mood, he had constructed a new tenet for himself; reflections leading to a belief in the absurdity of sex. Two bodies, clasped and sundered, as someone said. Limbs in dance performing all their rituals and rites. Another.

He had lived according to this belief for many years, an abstraction wrought from these items: a shining, bull-vacant cast to his eyes; rubberized skin hanging loose on his face; a jaw, now first noticed, that dropped slack and rocked uncontrolled in time with the mattress springs under him. The object of his rhythmic attentions soon withered in his hand, unreleased. He sat there, a few minutes more, on the edge of his bed. Quiet, still. Staring at the image in the mirror that stared back at him. Dimorphic. Each, in spatial solitude and different dimension. He gave up the image-eye's challenge finally. Turned his gaze to his hands and his mind to his body, and declared that he would not be so: that he would not allow himself to be in the grasp of something his mind was not superior to. The contradiction in his statement, the implied mutual exclusion of allowance and grasp, was something he had never worked out. It was enough for him, at that point in time, to have devised a formula. And though the formula did not always work, though absurdity of sex was accepted, the need and sex itself still found ways of recurring, he decided, in those rare cases, that it had only been the influence of a mood, a passing interference. A change in him, for those moments, not in the truth of what he believed.

But on this day in Emanuel's he recognized, for the first time, that it had been a random mood, a chance glance at a mirror, that had led to his original formulation, that was responsible for a philosophy of some passed-thirty years. That long a time with that narrow a thought as a beacon, as a guiding principle. An area, a segment, a portion, a span of who he was, or might have been, smothered for all that time. He spiraled downward for a moment, and took a larger, gulping drink from his cup. Not saying a word as he looked on and continued to reflect and think.

He accused himself of pseudo-intellectuality, of preposterousness and pretension. Vowed penance at the feet of the most egocentric and chastising god imaginable, to wash himself of self-deceptions, and let that god's mind be spent and muddled in trying to figure riddles out, to sort through to the core of these complications. The Philosopher saw through to a gigantic humor in all this, also; to the ironies, this one included, that clutch at man, and weigh him down, and leave him stranded and immobile on beaches not of his own choosing. A very small smile crept across his face.

But after that laughter he still knew that this was the man he was, that this was the way he thought. That he was that egocentric god, and a different man each day of his life. Who was a riddle and a complication, as all men are, but as so few are content to be.

And he realized, further, that this recent mood was only random, also, and all its reflections might be thrown out in a moment. Would be swept away by Stewy's broom in the morning.

He rose soundless from his corner and thought, buttoned his coat, and prepared to leave. It would be colder now, this late in the afternoon. Emanuel was eating a makeshift dinner at one corner of the bar. The Philosopher silently replaced his chair under the table, and cradling the coffee cup in one hand, walked to that side of the room. Emanuel looked up, and the Philosopher debated whether to say a good night. He chose not to, only permitting his gaze to fasten on Emanuel's eyes as the cup was placed within hands reach. Emanuel nodded his head to signify the harbor was in sight again, and the Philosopher's afternoon journey was over. Then he continued to chew on his sandwich; his way of making a smooth transition from one leg of a journey to another, his preparation for entry into the darking night. The Philosopher looked a moment longer, then turned on his heel and made his way to the door.

He could have spoken, but he didn't. It was not really necessary. It did not really matter.

Instead, he remained faithful to another chosen pose. He would be bemused by the joys of this world, and detached from its sorrow. He would walk out of Emanuel's, into an unconcerned night, and continue to contemplate: action is only manifestation of mood, also. And mood is constantly changing.

The only end he might have said he sought was to solve the riddle completely. Unwind the complications, narrow the modulations of life until the wave was flat and endless. Until existence was unrecognized, and he alone could scan the whole of it. A band of excitement, emotion, feeling compressed to a thin line; joy and sorrow meeting on the same plane. He was straightening a roller coaster's dips and curves until the coaster cars lost all their motion. Waiting for a point where he could safely board, sit quietly inside them, and consider that state further. Dreaming of a time when he and they and process ceased finally to exist.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNotes Towards a "Whole Life Catalog"

March 1973 By ALAN T. GAYLORD, DIRECTOR -

Feature

FeatureTHE ACRONYM SYNDROME

March 1973 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

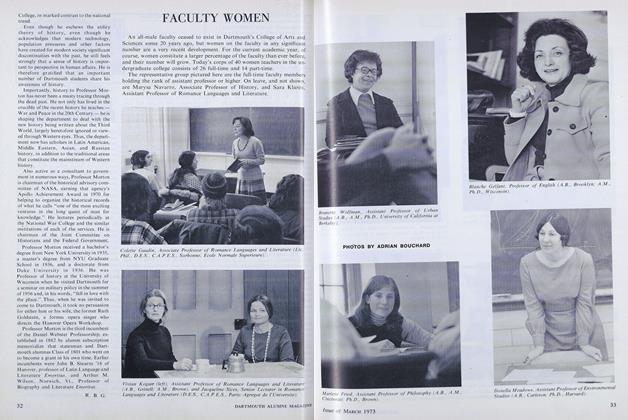

FeatureFACULTY WOMEN

March 1973 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL

March 1973 -

Article

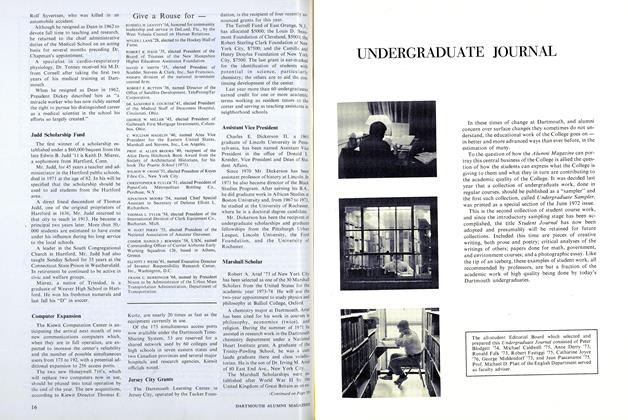

ArticleBrautigan's Search for Reality

March 1973 By RICHARD D. CARYOLTH '73 -

Article

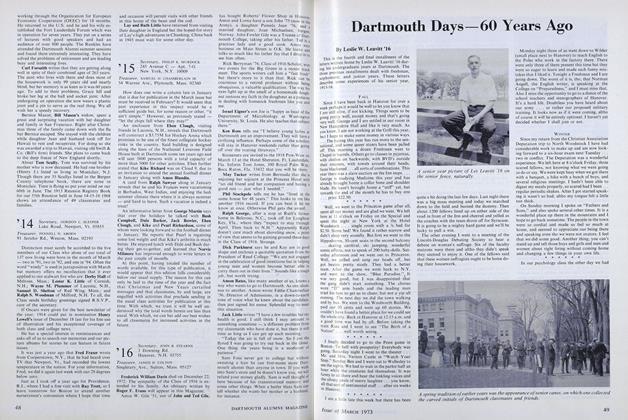

ArticleDartmouth Days—60 Years Ago

March 1973 By Leslie W. Leavitt '16

Features

-

Feature

FeatureArt Collector and Author

APRIL 1968 -

Cover Story

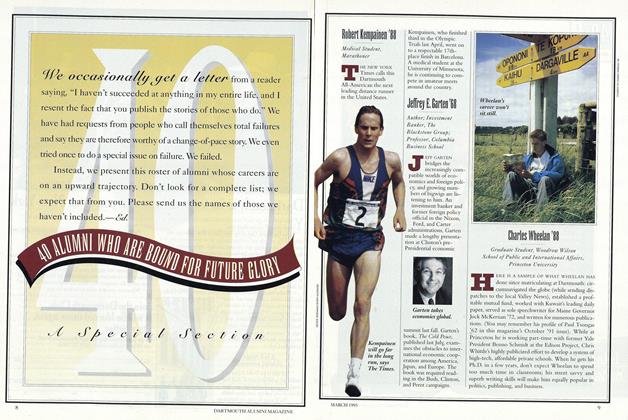

Cover StoryCharles Wheelan '88

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureDoubt and Passion: Notes on Contemporary American Novelists

OCTOBER, 1908 By Horace Porter -

Feature

FeatureThe Reynold Scholars

June 1956 By PROF. JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureThe Quest for Quality

JULY 1965 By STEWART LEE UDALL, LL.D. '65 -

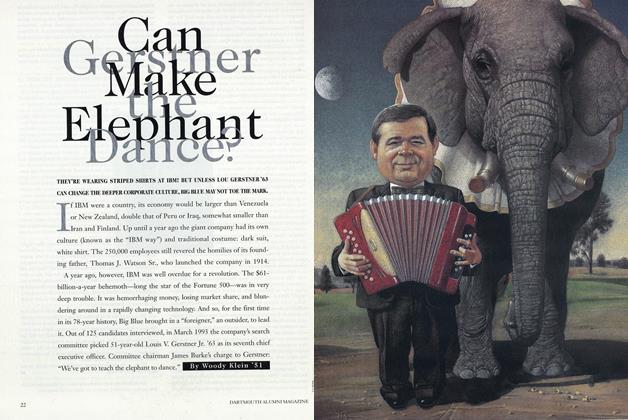

Feature

FeatureCan Gerstner Make the Elephant Dance?

MARCH 1994 By Woody Klein '51