Lincoln Filene Professorof Human Relations

IN the light of recent years, when the voice of Cassandra seems to have overpowered the "voice of the turtle" throughout the land, one might think that 38 vears of study of the social condition would produce a severe case of cynicism. In what passes for the conventional view of college youth in the wake of recent turbulence. one would understand if George Theriault confessed to being a bit weary - even a bit jaded - after decades of confronting fronting the mercurial, insistent egos of young adults.

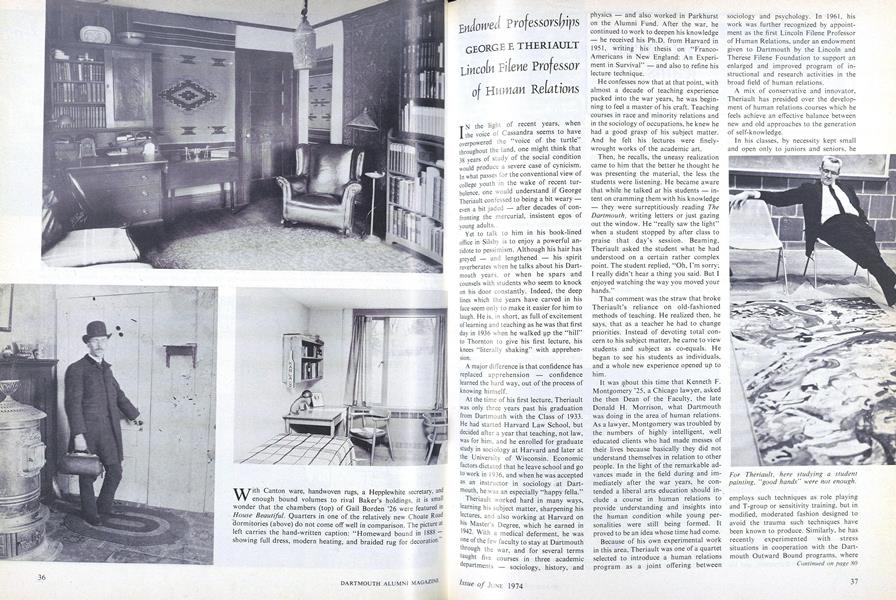

Yet to talk to him in his book-lined office in Silsby is to enjoy a powerful antidote to pessimism. Although his hair has greyed - and lengthened - his spirit reverberates when he talks about his Dartmouth years, or when he spars and counsels with students who seem to knock on his door constantly. Indeed, the deep lines which the years have carved in his face seem only to make it easier for him to laugh. He is, in short, as full of excitement of learning and teaching as he was that first day in 1936 when he walked up the "hill" to Thornton to give his first lecture, his knees "literally shaking" with apprehension.

A major difference is that confidence has replaced apprehension - confidence learned the hard way, out of the process of knowing himself.

At the time of his first lecture, Theriault was only three years past his graduation from Dartmouth with the Class of 1933. He had started Harvard Law School, but decided after a year that teaching, not law, was for him, and he enrolled for graduate study in sociology at Harvard and later at the University of Wisconsin. Economic factors dictated that he leave school and go to work in 1936, and when he was accepted as an instructor in sociology at Dartmouth, he was an especially "happy fella."

Theriault worked hard in many ways, learning his subject matter, sharpening his lectures, and also working at Harvard on his Master's Degree, which he earned in 1942. With a medical deferment, he was one of the few faculty to stay at Dartmouth through the war, and for several terms taught five courses in three academic department - sociology, history, and physics - and also worked in Parkhurst on the Alumni Fund. After the war, he continued to work to deepen his knowledge - he received his Ph.D. from Harvard in 1951, writing his thesis on "Franco-Americans in New England: An Experiment in Survival" - and also to refine his lecture technique.

He confesses now that at that point, with almost a decade of teaching experience packed into the war years, he was beginning to feel a master of his craft. Teaching courses in race and minority relations and in the sociology of occupations, he knew he had a good grasp of his subject matter. And he felt his lectures were finely-wrought works of the academic art.

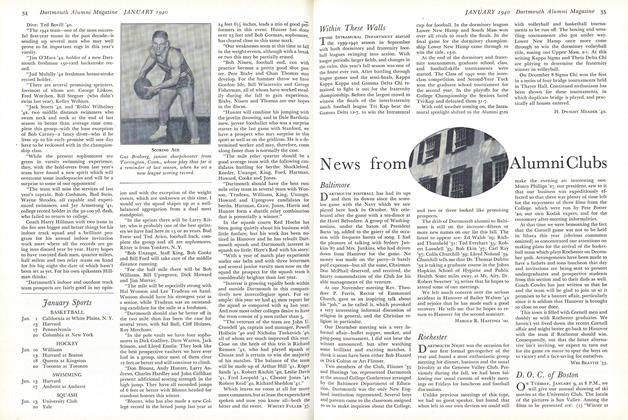

Then, he recalls, the uneasy realization came to him that the better he thought he was presenting the material, the less the students were listening. He became aware that while he talked at his students - intent on cramming them with his knowledge - they were surreptitiously reading TheDartmouth, writing letters or just gazing out the window. He "really saw the light" when a student stopped by after class to praise that day's session. Beaming, Theriault asked the student what he had understood on a certain rather complex point. The student replied, "Oh, I'm sorry; I really didn't hear a thing you said. But I enjoyed watching the way you moved your hands."

That comment was the straw that broke Theriault's reliance on old-fashioned methods of teaching. He realized then, he says, that as a teacher he had to change priorities. Instead of devoting total concern to his subject matter, he came to view students and subject as co-equals. He began to see his students as individuals, and a whole new experience opened up to him.

It was about this time that Kenneth F. Montgomery '25, a Chicago lawyer, asked the then Dean of the Faculty, the late Donald H. Morrison, what Dartmouth was doing in the area of human relations. As a lawyer, Montgomery was troubled by the numbers of highly intelligent, well educated clients who had made messes of their lives because basically they did not understand themselves in relation to other people. In the light of the remarkable advances made in the field during and immediately after the war years, he contended a liberal arts education should include a course in human relations to provide understanding and insights into the human condition while young personalities were still being formed. It proved to be an idea whose time had come.

Because of his own experimental work in this area, Theriault was one of a quartet selected to introduce a human relations program as a joint offering between sociology and psychology. In 1961. his work was further recognized by appointment as the first Lincoln Filene Professor of Human Relations, under an endowment given to Dartmouth by the Lincoln and Therese Filene Foundation to support an enlarged and improved program of instructional and research activities in the broad field of human relations.

A mix of conservative and innovator. Theriault has presided over the development of human relations courses which he feels achieve an effective balance between new and old approaches to the generation of self-knowledge.

In his classes, by necessity kept small and open only to juniors and seniors, he employs such techniques as role playing and T-group or sensitivity training, but in modified, moderated fashion designed to avoid the trauma such techniques have been known to produce. Similarly, he has recently experimented with stress situations in cooperation with the Dartmouth Outward Bound programs, where natural or wilderness settings provide the testing arena. This experiential learning is constantly illuminated by lectures, reading, journals and papers. Theriault also makes it his business to know the students as well as do their parents.

As a result, a Theriault class is more than a class. It is a way of life, with students voluntarily meeting together for extra sessions on weekends, or for lunch or dinner to carry on their projects, which may include living in a blacked-out bomb shelter, bushwacking cross-country for three days, or making a television play. And after the course is finished, invariably many of the students continue to meet, giving formal expression to the friendships they made and the reinforcement they received while in the class. Theriault is already receiving a steady stream of advance applications for the classes remaining before his scheduled retirement in 1976.

And, as with all good teachers, Theriault continues to hear from his former students for years after they Rave gone out from Dartmouth. They write back to keep him informed of marriages, children or new career directions, and the letters invariably express appreciation for the way a teacher managed to help each know himself.

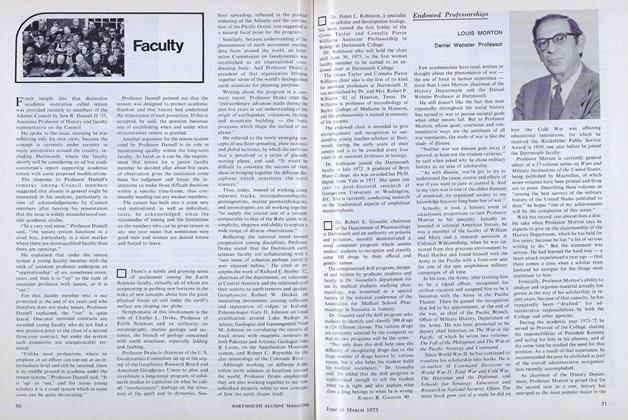

For Theriault, here studying a studentpainting, "good hands" were not enough.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEducation in the Round

June 1974 By ANDREW J. NEWMAN AND MELANIE FISHER -

Feature

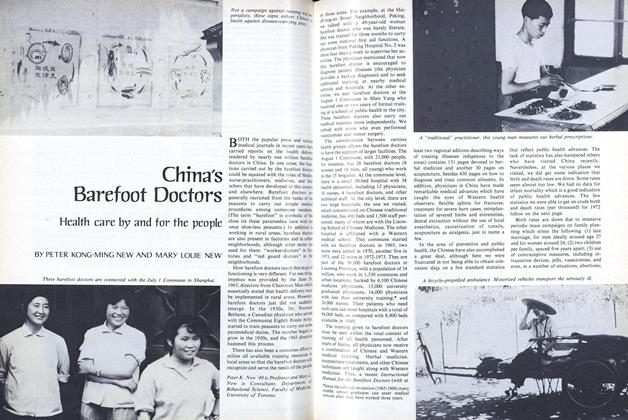

FeatureChina's Barefoot Doctors

June 1974 By PETER KONG-MING NEW AND MARY LOUIE NEW -

Feature

FeatureCASTLES ON THE CONNECTICUT

June 1974 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

FeatureO Pioneers

June 1974 -

Feature

FeatureRetiring Professors

June 1974 -

Article

ArticleRetirement: Plan It and Enjoy

June 1974 By RICHARD S. BURKE '29