Winkley Professor of Anglo - Saxon and English Literature

CONTEMPLATING the chorus of disillusionment in latterday American literature, to which he is now returning in increasing measure, Harry Bond cites Hemingway's Nick Adams who is described as being "shellshocked by life."

"America is experiencing the rediscovery of sin," Bond insists, "in a sense relearning in secular terms the Biblical view of human fallibility, weakness, and corruptibility. It's really an age-old battle, this continuing struggle of man, and the attempt to create a moral awareness and sensitivity to it is what the teaching of the humanities is all about."

Yet Bond is essentially an optimist, a point of departure that keeps surfacing in his talks about literature, as when he cites Frost's moving poem "Directive." He interprets that poetic description of a journey back to an abandoned farm house as a song of triumph, even in defeat, a statement of the essential continuity of man's eternal quest. Or, in the context of the Old Testament, he will point to the "saving remnant," the few whom the Lord promised Isaiah would ultimately be saved. "As I read that story," Bond says, "it highlights the concept that there's enough good and fair to make the struggle worthwhile."

And at the risk of sounding profane, he adds, "What makes teaching at Dartmouth so exciting is that most of the students we get here fall into that category" - with each generation containing the seeds of great potential and of hope.

Synthesis becomes an art form as it is practiced by Bond, whose academic title as the Henry Winkley Professor of Anglo-Saxon and English Languages and Literature only describes a fraction of the whole man.

In addition to his roles as scholar and teacher, he is an ardent outdoorsman harking back to his days as president of the Dartmouth Outing Club. At least once every year he climbs the 4,810-foot peak of Mt. Moosilauke, on which he ranged as an undergraduate during three summers as a "hut boy" at the former summit house. Each winter, he periodically quits the cozmess of his office in Sanborn House for the etched landscape of the ski trail.

An expert horticulturist, he finds rich emotional nurture in turning the greenhouse he built alongside his rambling hillside house into an oasis of year-long bloom.

Articulate, casual with a touch of elegance that old tweeds cannot hide, Bond presents the quintessence of the civilized New Englander. Yet behind the wry smile, which seems to mask in incipient skepticism his enthusiasm for life, there's a toughness and earthiness, in the best sense of that term, ingrained during his own trial by fire in World War II.

Although the events are now remote in time, Bond came to know war at its rawest when, fresh from the Dartmouth campus, he served as an infantry officer from Morocco to Austria. His book, Return toCassino, is both a graphic account of the battle to take that mountain abbey, which the Germans had made the keystone to a natural fortress athwart the road to Rome, and a sensitive evocation of the point and counterpoint of war and peace. At Cassino he led a mortar platoon in a numbing duel in lives until he was knocked out of action and evacuated from the carnage.

Happily, Bond's three years of war were immediately tempered by a return to studies as a graduate student at Harvard, where he earned an M.A. in 1949 and a doctorate in 1955, while also teaching variously at M.I.T. (1946-47), Wellesley (1951-52), and Dartmouth twice (1947-48 and 1949-50) before starting his long-term association with the Dartmouth faculty in 1952.

Perhaps prophetically, Bond began his academic career nearly 30 years ago specializing in that golden age of English letters which produced Shakespeare, Spenser, Marlowe, Donne, Bacon, and Ben Jonson. He gained early recognition as an authority on the 18th-century historian Edward Gibbon, about whose literary art Bond has written one book and whose life and works continue to engage him.

Yet, like the giants of the English Renaissance who formed his early interests, Bond broke out of the traditional constraints of specialization to become a generalist in his discipline. No longer tied to any era or school of writing, he now ranges through the essence of man as distilled in literature from the sublime insights of the prophets of the Old Testament to the stark and secular statements of good and evil, hope and despair in the modern idiom of Kurt Vonnegut.

Bond's undergraduate courses reflect his successive areas of research: English Renaissance - (he remains persuaded that "we all are enriched, more developed spiritually and morally for having read and known Shakespeare"); English Romantic Poets - (who gave voice to man's emotional turbulence, the Sturm undDrang which rationalists of the Enlightenment like Gibbon could neither harness nor understand); and the King James' version of the Bible. He began to teach the latter - as literature - about eight years ago after having been appalled by his students' ignorance of the Bible and moved by their secular interest in it.

Meanwhile, Bond has added still another dimension to his teaching as a result of his work in helping pioneer continuing education at Dartmouth. Every summer from 1964, when Dartmouth started its novel concept of continuing academic commitment to its graduates, until 1969, he served on the Alumni College faculty in addition to his undergraduate teaching assignments. For three years he was academic director of the program. From 1967 to 1971, he also represented the Dartmouth faculty on the Alumni Council. Then, drawing on Bond's experience in teaching and relating to men of affairs, President Kemeny appointed him in 1971 as faculty director to inaugurate the Dartmouth Institute, which this summer completed its third month-long refresher course in the liberal arts for leaders of business, government, and the professions.

Equally at home now with academicians and corporate leaders, undergraduates and alumni, he seems to have broken the age barriers in communication, earning almost simultaneously the accolade of "immortal spirit" from undergraduates (in a recent Course Guide) and standing ovations from mature executives.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"THE KINGDOM OF GOD HAS COME"

October 1974 By MARy BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

FeatureMore than a beast, Less than an angel

October 1974 By PETER A. BIEN -

Feature

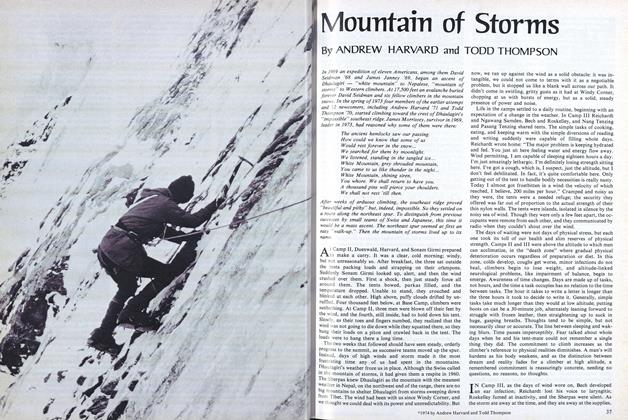

FeatureMountain of Storms

October 1974 By ANDREW HARVARD, TODD THOMPSON -

Feature

FeatureBelieve It or Not!

October 1974 By GREGORY C. SCHWARZ -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

October 1974 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

October 1974 By WALTER C. DODGE, DR. THEODORE MINER

R.B.G.

-

Article

ArticleIt's Still "Men of Dartmouth"

NOVEMBER 1972 By R.B.G. -

Article

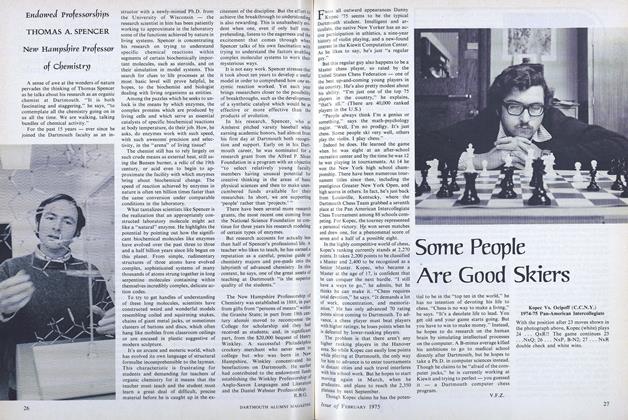

ArticleEndowed Professorships

MARCH 1973 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleS. MARSH TENNEY

May 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleGEORGE F. THERIAULT

June 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleHELEN L. ROBINSON

November 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleTHOMAS A. SPENCER

February 1975 By R.B.G.

Article

-

Article

ArticleWILLIAM NILES '59 DIES AGE NINETY, IN INDIANA

March, 1926 -

Article

ArticleSituation Stabilized

March 1951 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleWorkin on the Railroad

March 1976 By D.M.S. -

Article

ArticleDiana Taylor, Act One: Gold Scissor Earrings

MAY 1997 By Heather McCatchen '87 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH CAVALRY IN THE CIVIL WAR

JUNE, 1927 By John Scales '63 -

Article

ArticleNew York

January 1940 By Malcolm G. Rollins '11