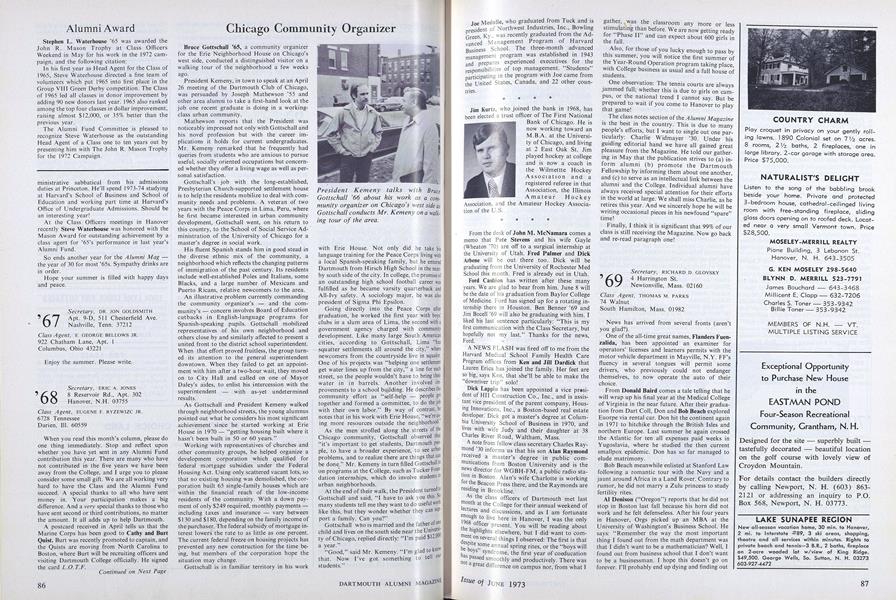

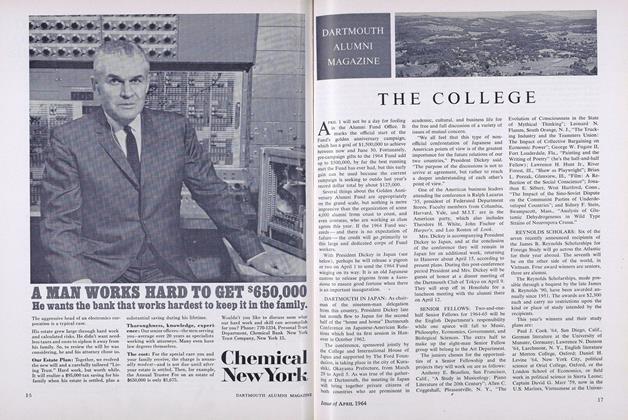

Bruce Gottschall '65, a community organizer for the Erie Neighborhood House on Chicago's west side, conducted a distinguished visitor on a walking tour of the neighborhood a few weeks ago.

President Kemeny, in town to speak at an April 26 meeting of the Dartmouth Club of Chicago, was persuaded by Joseph Mathewson '55 and other area alumni to take a first-hand look at the job one recent graduate is doing in a working-class urban community.

Mathewson reports that the President was noticeably impressed not only with Gottschall and his novel profession but with the career implications it holds for current undergraduates. Mr. Kemeny remarked that he frequently had queries from students who are anxious to pursue useful, socially oriented occupations but concerned whether they offer a living wage as well as personal satisfaction.

Gottschall's job with the long-established, Presbyterian Church-supported settlement house is to help the residents mobilize to deal with community needs and problems. A veteran of two years with the Peace Corps in Lima, Peru, where he first became interested in urban community development, Gottschall went, on his return to this country, to the School of Social Service Administration of the University of Chicago for a master's degree in social work.

His fluent Spanish stands him in good stead in the diverse ethnic mix of the community, a neighborhood which reflects the changing patterns of immigration of the past century. Its residents include well-established Poles and Italians, some Blacks, and a large number of Mexicans and Puerto Ricans, relative newcomers to the area.

An illustrative problem currently commanding the community organizer's - and the community's - concern involves Board of Education cutbacks in English-language programs for Spanish-speaking pupils. Gottschall mobilized representatives of his own neighborhood and others close by and similarly affected to present a united front to the district school superintendent. When that effort proved fruitless, the group turned its attention to the general superintendent downtown. When they failed to get an appointment with him after a two-hour wait, they moved on to City Hall and called on one of Mayor Daley's aides, to enlist his intercession with the superintendent - with as-yet undetermined results.

As Gottschall and President Kemeny walked through neighborhood streets, the young alumnus pointed out what he considers his most significant achievement since he started working at Erie House in 1970 - "getting housing built where it hasn't been built in 50 or 60 years."

Working with representatives of churches and other community groups, he helped organize a development corporation which qualified for federal mortgage subsidies, under the Federal Housing Act. Using only scattered vacant lots, so that no existing housing was demolished, the corporation built 65 single-family houses which are within the financial reach of the low-income residents of the community. With a down payment of only $249 required, monthly payments - including taxes and insurance - vary between $ 130 and $ 180, depending on the family income of the purchaser. The federal subsidy of mortgage interest lowers the rate to as little as one percent. The current federal freeze on housing projects has prevented any new construction for the time being, but members of the corporation hope the situation may change.

Gottschall is in familiar territory in his work with Erie House. Not only did he take his language training for the Peace Corps living with a local Spanish-speaking family, but he entered Dartmouth from Hirsch High School in the nearby south side of the city. In college, the promise of an outstanding high school football career was fulfilled as he became varsity quarterback and All-Ivy safety. A sociology major, he was also president of Sigma Phi Epsilon.

Going directly into the Peace Corps after graduation, he worked the first year with boys' clubs in a slum area of Lima, the second with a government agency charged with community development. Like many large South American cities, according to Gottschall, Lima "has squatter settlements all around the city," where newcomers from the countryside live in squalor. One of his projects was "helping one settlement get water lines up from the city," a line for each street, so the people wouldn't have to bring their water in in barrels. Another involved improvements to a school building. He describes the community effort as "self-help - people got together and formed a committee, to do the job with their own labor." Byway of contrast, he notes that in his work with Erie House, "we're using more resources outside the neighborhood.

As the men strolled along the streets of the Chicago community, Gottschall observed that "it's important to get students, Dartmouth people, to have a broader experience, to see urban problems, and to realize there are things that can be done." Mr. Kemeny in turn filled Gottschall in on programs at the College, such as Tucker Foundation internships, which do involve students in urban neighborhoods.

At the end of their walk, the President turned to Gottschall and said, "I have to ask you this. So many students tell me they want to do useful work like this, but they wonder whether they can support a family. Can you?"

Gottschall who is married and the father of one child and lives on the south side near the University of Chicago, replied directly: "I'm paid $12,000 a year."

"Good," said Mr. Kemeny. "I'm glad to know that. Now I've got something to tell our students."

President Kemeny talks with BruceGottschall '66 about his work as a community organizer on Chicago's west side asGottschall conducts Mr. Kemeny on a walking tour of the area.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHow the Dutch Handle It

June 1973 By Robert D. Haslach '68 -

Feature

FeatureTHE FIRST COED YEAR

June 1973 By Bruce Kimball '73 and Andrew Newman '74 -

Feature

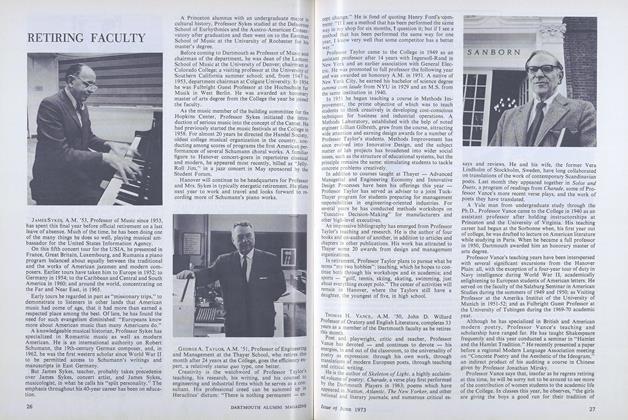

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1973 -

Feature

FeatureClass Officers Weekend

June 1973 -

Feature

FeatureAvalanche Authority

June 1973 -

Feature

FeatureEditors' Editor

June 1973 By MARY ROSS

Article

-

Article

ArticleA FORGOTTEN BATTLE

November, 1915 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Meeting

May 1940 -

Article

ArticleMerchant Marine

August 1942 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH IN JAPAN

APRIL 1964 -

Article

ArticleNoted Townies of the Past and Present

January 1935 By "Old Timer" -

Article

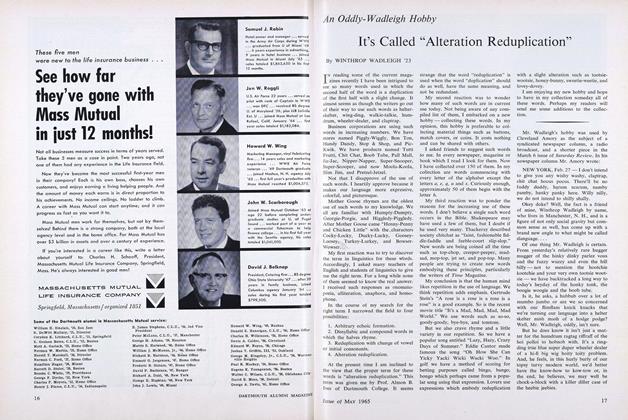

ArticleIt's Called "Alteration Reduplication"

MAY 1965 By WINTHROP WADLEIGH '23