Few will dispute the dictum that the first essential in college assets is a staff of competent teachers, capable of interesting and inspiring their students, and adequately paid. More debate has arisen out of conflicting beliefs as to what criteria should guide in selecting such a staffwhether such should be chosen with reference to "productive" scholarship first of all, and what should be the best evidence of such scholarship.

The chief question naturally arises in the case of new-hatch'd, unfledged academicians, who have not yet had time to do much scholarly research and still less time to publish results as the proof of their productivity. Hence the tendency to fall back on the possession of the degree of Ph.D. as a quintessential sine qua non. That has come to be the guinea's stamp, or a sort of visa on the young teacher's passport to promotion and pay, if not to initial acceptance as a candidate for the college faculty. It has come to be assumed that if a young teacher is to expect advancement he must possess a doctorate of philosophy.

Obviously this degree is actual evidence only of the fact that the aspirant has done some intensive research in some chosen field, has passed some written and oral tests, and has submitted a' satisfactory thesis on some phase of his work—very likely has published it. It does not guarantee that the candidate's life hereafter will be devoted to research; and as a matter of fact comparatively few actually do so, once they are embarked on a teacher's career. But they have at least demonstrated capacity for it as an evidence of good faith, and perhaps this criterion is the best there is for the purpose. Anyhow the Ph.D. is widely accepted as the key to the academic door.

Even more obviously the Ph.D. guarantees nothing as to the aspirant's qualification to become an interesting and inspiring teacher—which, after all, would seem to be the important thing. That, however, is something which is not easily to be avouched by antecedent tests. At least it can hardly be claimed that the Ph.D. does any harm, but, so far as it goes, is some evidence for the good. It may be wise not to exaggerate its importance—a very different thing from decrying it.

It may be well, also, not to exaggerate "productive" scholarship as an essential in a teaching staff, especially in colleges where graduate study is a secondary matter, if it exists at all. Admittedly an array of well-known academic experts, men recognized as authoritative scholars in their chosen specialties, is good window-dressing; and it would be folly to rush to the conclusion that a productive scholar cannot be an inspiring teacher merely because his chief interest is otherwise engaged. But should an inspiring teacher be handicapped because he is not also a productive scholar with volumes of printed pages to his credit? Should he be made to feel that the watchword is "publish or perish" and that unless he can make a name for himself as a productive scholar he labors in vain? There has been a trend in that direction throughout the collegiate world—and it may well be that it is a thing to abide our question.

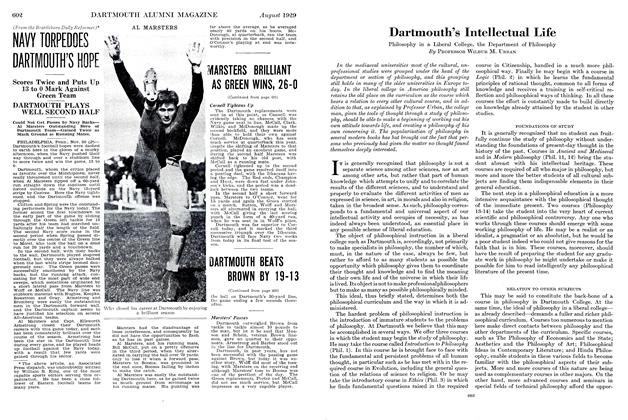

IN THE EARLY-SPRING SUN A GIANT ELM NEAR ROLLINS CHAPEL CASTS A GRACEFUL SHADOW

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE WHITE CHURCH

May 1946 By PROFS. FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 and ERNEST BRAD LEE WATSON '02 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

May 1946 By Rolf C. Syvertsen M'22. -

Article

ArticleTwo Commonwealths: One World

May 1946 By THOMAS S. K. SCOTT-CRAIG -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleThe Role of the Humanities

May 1946 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Article

ArticleJESS B. HAWLEY '09

May 1946 By SIDNEY C. HAZELTON '09

P. S. M.

-

Article

ArticleNot So Useless

August 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleAn Item To Budget

December 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleIntercollegiate Interim

January 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleWho Calls the Tune?

April 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleDos Pou Sto

February 1945 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleWorld Organization

May 1945 By P. S. M.

Article

-

Article

ArticleNEW DARTMOUTH CLUB

OCTOBER 1931 -

Article

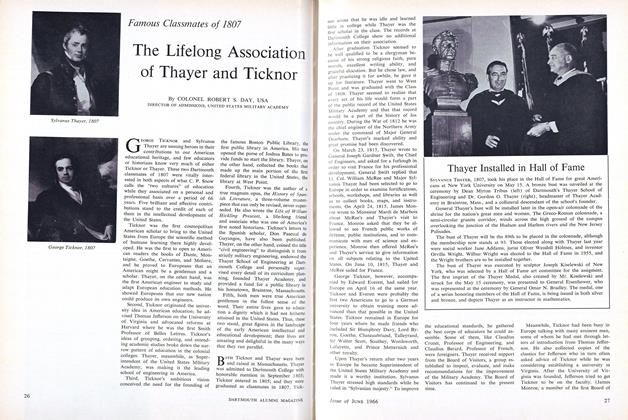

ArticleThayer Installed in Hall of Fame

JUNE 1966 -

Article

Article"Z" Day in Hartford

MAY 1972 -

Article

ArticleFraternities Should Be Banned

MARCH 1992 -

Article

ArticleCreative Housing Option

NOVEMBER 1999 By Meeta Agrawal '01 -

Article

ArticleFOUNDATIONS OF STUDY

AUGUST 1929 By Professor Wilbur M. Urban