In June, 1964, a decade past Little Rock, a year after the March on Washington, 55 "disadvantaged boys" arrived in Hanover, N.H., for a summer term of high school at Dartmouth College.

While Harlem stirred restlessly in the first of those long hot summers, the 44 Negroes, 5 Puerto Ricans, 3 whites, 2 Chinese, and 1 American Indian unpacked their belongings and assembled for an orientation session.

As the Free Speech Movement blossomed at Berkeley, these boys were told, "You've come here to prove you can make it in the best private secondary schools in the country. We've got your return tickets here, and if you're smart you'll get back on the bus and go home.

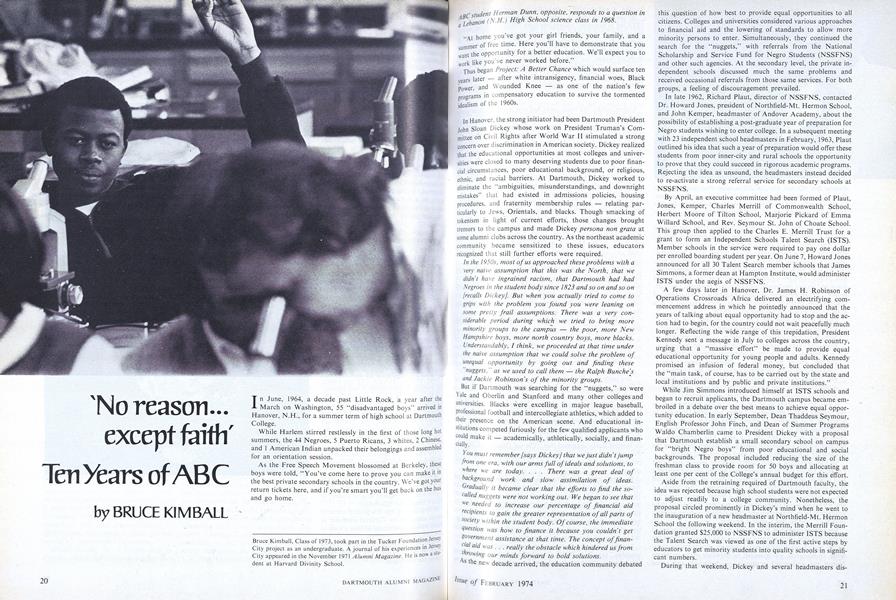

ABC student Herman Dunn, opposite, responds to a question ina Lebanon (N.H.) High School science class in 1968.

“At home you've got your girl friends, your family, and a summer of free time. Here you'll have to demonstrate that you want the opportunity for a better education. We'll expect you to work like you've never worked before."

Thus began Project: A Better Chance which would surface ten years later - after white intransigency, financial woes, Black Power, and Wounded Knee - as one of the nation's few programs in compensatory education to survive the tormented idealism of the 1960s.

In Hanover, the strong initiator had been Dartmouth President John Sloan Dickey whose work on President Truman's Committee on Civil Rights after World War II stimulated a strong concern over discrimination in American society. Dickey realized that the educational opportunities at most colleges and universities were closed to many deserving students due to poor financial circumstances, poor educational background, or religious, ethnic, and racial barriers. At Dartmouth, Dickey worked to eliminate the "ambiguities, misunderstandings, and downright mistakes" that had existed in admissions policies, housing procedures, and fraternity membership rules - relating particularly to jews, Orientals, and blacks. Though smacking of tokenism in light of current efforts, those changes brought tremors to the campus and made Dickey persona non grata at some alumni clubs across the country. As the northeast academic community became sensitized to these issues, educators recognized that still further efforts were required.

In the 1950s, most of us approached these problems with avery naive assumption that this was the North, that wedidn't have ingrained racism, that Dartmouth had hadNegroes in the student body since 1823 and so on and so onIrecalls Dickey], But when you actually tried to come togrips with the problem you found you were leaning onsome pretty frail assumptions. There was a very considerable period during which we tried to bring moreminority groups to the campus - the poor, more NewHampshire boys, more north country boys, more blacks.Understandably, I think, we proceeded at that time underthe naive assumption that we could solve the problem ofunequal opportunity by going out and finding these“nuggets," as we used to call them - the Ralph Bunche'sand Jackie Robinson's of the minority groups.

But if Dartmouth was searching for the "nuggets," so were Yale and Oberlin and Stanford and many other colleges and universities. Blacks were excelling in major league baseball, professional football and intercollegiate athletics, which added to their presence on the American scene. And educational institutions competed furiously for the few qualified applicants who could make it - academically, athletically, socially, and financially.

You must remember [says Dickey] that we just didn't jumpfrom one era, with our arms full of ideals and solutions, towhere we are today. . . . There was a great deal ofbackground work and slow assimilation of ideas.Gradually it became clear that the efforts to find the so-called nuggets were not working out. We began to see thatWe needed to increase our percentage of financial aidrecipients to gain the greater representation of all parts ofsociety within the student body. Of course, the immediatequestion was how to finance it because you couldn't getgovernment assistance at that time. The concept of financialaid was . . . really the obstacle which hindered us fromthrowing our minds forward to bold solutions.

As the new decade arrived, the education community debated this question of how best to provide equal opportunities to all citizens. Colleges and universities considered various approaches to financial aid and the lowering of standards to allow more minority persons to enter. Simultaneously, they continued the search for the "nuggets," with referrals from the National Scholarship and Service Fund for Negro Students (NSSFNS) and other such agencies. At the secondary level, the private independent schools discussed much the same problems and received occasional referrals from those same services. For both groups, a feeling of discouragement prevailed.

In late 1962, Richard Plaut, director of NSSFNS, contacted Dr. Howard Jones, president of Northfield-Mt. Hermon School, and John Kemper, headmaster of Andover Academy, about the possibility of establishing a post-graduate year of preparation for Negro students wishing to enter college. In a subsequent meeting with 23 independent school headmasters in February, 1963, Plaut outlined his idea that such a year of preparation would offer these students from poor inner-city and rural schools the opportunity to prove that they could succeed in rigorous academic programs. Rejecting the idea as unsound, the headmasters instead decided to re-activate a strong referral service for secondary schools at NSSFNS.

By April, an executive committee had been formed of Plaut, Jones, Kemper, Charles Merrill of Commonwealth School, Herbert Moore of Tilton School, Marjorie Pickard of Emma Willard School, and Rev. Seymour St. John of Choate School. This group then applied to the Charles E. Merrill Trust for a grant to form an Independent Schools Talent Search (ISTS). Member schools in the service were required to pay one dollar per enrolled boarding student per year. On June 7, Howard Jones announced for all 30 Talent Search member schools that James Simmons, a former dean at Hampton Institute, would administer ISTS under the aegis of NSSFNS.

A few days later in Hanover, Dr. James H. Robinson of Operations Crossroads Africa delivered an electrifying commencement address in which he pointedly announced that the years of talking about equal opportunity had to stop and the action had to begin, for the country could not wait peacefully much longer. Reflecting the wide range of this trepidation, President Kennedy sent a message in July to colleges across the country, urging that a "massive effort" be made to provide equal educational opportunity for young people and adults. Kennedy promised an infusion of federal money, but concluded that the "main task, of course, has to be carried out by the state and local institutions and by public and private institutions."

While Jim Simmons introduced himself at ISTS schools and began to recruit applicants, the Dartmouth campus became embroiled in a debate over the best means to achieve equal opportunity education. In early September, Dean Thaddeus Seymour, English Professor John Finch, and Dean of Summer Programs Waldo Chamberlin came to President Dickey with a proposal that Dartmouth establish a small secondary school on campus for "bright Negro boys" from poor educational and social backgrounds. The proposal included reducing the size of the freshman class to provide room for 50 boys and allocating at least one per cent of the College's annual budget for this effort.

Aside from the retraining required of Dartmouth faculty, the idea was rejected because high school students were not expected to adjust readily to a college community. Nonetheless, the proposal circled prominently in Dickey's mind when he went to the inauguration of a new headmaster at Northfield-Mt. Hermon School the following weekend. In the interim, the Merrill Foundation granted $25,000 to NSSFNS to administer ISTS because the Talent Search was viewed as one of the first active steps by educators to get minority students into quality schools in significant numbers.

During that weekend, Dickey and several headmasters discussed the problems of "nugget-recruiting." Here they faced a mutual problem from different levels and pondered how their joint resources could be used to make equal opportunity a reality. Returning to Hanover, Dickey talked further with Chamberlin, Seymour, Associate Dean Charles Dey who had returned from Peace Corps work in the Philippines, and other administrators and faculty. This prompted an October meeting with Howard Jones and his two headmasters which in turn produced The Dartmouth College Proposal to help "capable but culturally and educationally deprived" youngsters, as Jones described it in a letter to the Executive Committee of ISTS:

Dartmouth College would like to cooperate with us byoffering an 8-week, 1964 Remedial and Tutorial SummerSession for forty 9th and 10th graders. ... Boys and girls,white and Negro, would be welcomed into the program.... Dartmouth will cover all expenses including salariesand will charge no tuition. . . . Hopefully, one of ourschools would, upon recommendation from Mr. Simmonsand following normal application for admissions, havealready accepted these young people contingent upon theirsuccessful completion of the Dartmouth experience.

It was, by all standards of the day, a radical proposition - a marvelously radical proposition. Dickey appointed Dean Dey to direct the first summer program. Then Dickey took the unprecedented step of personally writing the funding proposal to demonstrate his concern for the idea. The Dartmouth administration felt confident of securing a sizeable grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to help fund the summer session.

To that point, the Talent Search summer session was called Project XYZ for lack of a proper title. One day, Dickey entered a staff meeting and suggested that they at least get the students off at the start of the alphabet. Then, he remembers, "It suddenly hit me ... we could call it Project ABC: A Better Chance. After all, that's what we were talking about all this time. We wanted these youngsters from 'disadvantaged' backgrounds to have a better chance ... and so that's what it became."

Soon the Rockefeller Foundation made a $150,000 grant to operate the first three summer sessions with Dartmouth and the Talent Search assuming an equal share in administrative costs. Since co-education was expected to introduce many problems beyond the anticipated academic, psychological, and social hurdles, it was decided to make the first summer all-male.

By the end of 1963, a widening split between NSSFNS and ISTS led to Simmons' resignation from NSSFNS. After several phone calls to Howard Jones and to Dartmouth, which agreed to provide office space and secretarial help, Simmons threw his files in cardboard boxes into his trunk, and drove through the New England winter to Hanover. Located in the basement of Parkhurst Hall, ISTS formally seceded from NSSFNS. In a subsequent memo to the Executive Committee, Jones concluded that "Regardless of present trauma, we have a very promising future."

Unfortunately, the break-away had cost Simmons three weeks of recruiting for 1964-65 admissions, in addition to the original time lag when the program began. He also had to return to the 30 ABC-ISTS members to talk about a new kind of student The private schools realized from the beginning that they would have to look for different criteria in admitting students through the Talent Search. Standardized test scores, IQ scores, and rank in class might have to be waived or placed secondary to a personal evaluation of the student's potential and motivation "to make it." Still, the schools expected strong assurances that the student would graduate and enter college.

As Simmons traveled from Gunnery to Wilbraham to St. Paul's and the rest, he spoke about admitting the "academic risk," the real target of Project: A Better Chance. This was the student from a poor educational or cultural background who showed great promise but who would arrive without the certainty of success. As Dr. Martin Luther King had described, it was the child who, unless someone intervened in his life, would probably never develop his potential as a human being.

In most cases, the independent school was expected to supply $3,000-4,000 in scholarship aid per year for this student whom Simmons intended to find in Harlem, Appalachia, and the deep South. At the ABC summer program the student would receive a rigorous initiation into the private school atmosphere to indicate the stature of his chances, academically and socially.

John Dickey remembers the problems of explaining the concept:

We got calls from high schools and guidance counselorsasking us what we were up to: Did we know what we weredoing? This boy is going to Dartmouth College for twomonths? But Dartmouth takes only students with highSAT scores, and this boy has trouble with his multiplication tables. ... We had to convince parents that we weren'ttrying to baby-snatch. And we had to bring the privateschools along.

Aside from the strongly enthusiastic such as Northfield-Mt. Hermon and Andover, some schools began to feel uneasy about Dartmouth's increased presence as the months passed - particularly reflecting the new emphasis on "the academic risk" over the previous search for "nuggets." A memo from one headmaster to Howard Jones suggested that "The tail [Dartmouth Summer Program] is wagging the dog [the 30 independent schools] by promoting its idea of whom the independent schools should accept."

By April, only 13 contingent admissions had been received from private schools out of 50 projected places in the summer. In Hanover, the ABC administrators frantically tried to find more acceptances for students that Simmons had recruited. Charles Dey offered assurances about the rigor of the summer program and promised that each school would receive a detailed evaluation of the student, with an option to withdraw its admission it the boy proved unmotivated or completely unprepared.

"At this point, the Dartmouth stamp of approval became invaluable," says Dean Waldo Chamberlin who helped coordinate the program. "Dartmouth invested her prestige and reputation behalf of those prestige-conscious places. Also, Northfield- Mt. Hermon and Andover were sticking their necks out, so these other schools, if they wanted to show a commitment, had little choice but to go along."

Meanwhile. Dey had planned a demanding eight-week program to test and prepare the boys academically, psychologically, and socially for the preparatory school atmosphere. A strict schedule kept them moving from 6:30 am to lights-out at 10:00 pm. The weekly morning class schedule included nine hours of English literature and composition, nine hours of mathematics, and six hours of reading instruction by teachers from Dartmouth and the private schools. In the afternoon were faculty appointments, required athletics, and an hour of free lime. After a formal dinner in coat and tie, the students had tutored study hall for three hours. Resident-tutors, Dartmouth undergraduates who lived with the boys in groups of seven, organized weekend trips in the New Hampshire countryside. Occasionally, special guests and speakers, such as Jackie Robinson, visited the ABC program. Everything was planned precisely to the last detail.

Chamberlin notes, "Of course, we were a little scared. We didn't have any choice but to be careful. I'm sure everyone was thinking silently: What if we fail? We could have thrown back the cause of equal opportunity education for years. We had to be prepared for everything and anything."

Finally, the 55 boys arrived with nearly all promised admission to secondary schools and Dey searching hurriedly for places for the remaining few. As a precursor of a problem which would later grow to trouble ABC, the hardest students to place were the whites. Thus, from the beginning, ABC had to face the conflict that it considered itself a program for the "culturally and educationally deprived" while others viewed it, used it, or criticized it as a program for minorities, specifically blacks. Certainly, minority peoples dominate the ranks of the "deprived" in the United States, but for ABC the criteria were the conditions, not the race.

Almost everyone finished that first summer smiling. The ABC faculty recommended 35 students on to their schools, recommended 12 with reservation, and did not recommend 8 boys. As testimony to their commitment, the independent schools accepted all of the first two groups and two of the last. The 49 completed the first year at their new schools, and all but two returned for the second year.

Barry Jones, a black student from a farm in Rustburg, Virginia, went to Groton and later graduated with honors from Dartmouth. Aside from the close friendships developed, he remembers that summer appreciatively for the study habits and personal discipline instilled through the rigorous demands. Beyond that, he believes, "You really have to give our parents a lot of credit. They didn't have to trust those people - people who look away their children and promised to educate them. There was no reason for trust, except faith. Certainly, our experience in this country did not lead us to trust them or expect anything from white educators in distant schools."

As the months passed and hundreds joined the Freedom Marches in the South, the girls schools in ABC-ISTS made righteous protests that it was time to include female students. Mt. Holyoke College offered to run a summer session for 50 girls and received a Rockefeller grant similar to the one obtained by Dartmouth. Planning continued through the winter as the number of member schools grew to 63 - 39 male, 12 female, 12 coeducational. Simmons added an assistant and a secretary to the staff to handle the increasing workload.

In Hanover, preparation for the 1965 summer session continued smoothly until mid-April when Jim Simmons received a phone call from Sargent Shriver, newly-appointed head of the newly-created Office of Economic Opportunity. In preceding months, Howard Jones had discussed the Talent Search with both Shriver and Congressman Adam Clayton Powell and received their blessings for the project. As the wheels of Washington influence turned, Shriver opened OEO with many funds allocated and few active programs, so he looked to one of the oldest and most prominent national programs in compensatory education: the fledgling ABC-ISTS.

"Can you take one thousand students this summer?" asked Shriver.

"That'll take a lot of money," said Simmons.

"Scare me with the figure."

"Ten million dollars."

"That doesn't scare me," replied Shriver.

ABC-ISTS would place a student only if guaranteed funds to see that student through his full secondary education. Thus, each pupil required about $10,000 - a summer program plus $3,000- 4,000 for 2-3 years. From this came the astronomical total.

However, money was not the only obstacle. Simmons knew he could find 1000 deserving students but finding 1000 places in the preparatory schools was a different matter. On top of that, Shriver was speaking to a two-man office with one-and-a-half secretaries in the basement of Parkhurst Hall at Dartmouth. It was certainly no operation to properly administer several million dollars. Since OEO had been legislated into existence for five years, a compromise was reached whereby ABC would take 100 students for the first year and 300 for each of the following three years.

From the 55 boys in 1964, ABC-ISTS sought to place 200 students during its second year: 100 from the Rockefeller grants given to Dartmouth and Mt. Holyoke plus private school scholarships and 100 from the OEO funds. This led to further expansion in staff, plans for a development office, and thoughts of moving the operation to Boston. Later that spring, the U.S. Office of Education made a $160,000 grant to ABC for a five- year study of the impact on participating students.

That summer, the Talent Search placed 44 students directly in preparatory schools, 82 in the Dartmouth summer session, and 72 in the Mt. Holyoke summer session. Of the latter two groups, 137 completed the program and entered independent schools in the fall.

As would be seen repeatedly, the success, even the survival of the ABC program, depended on the affectionate yet disciplined relationship between the students and the resident-tutors. Jack McCarthy, a 1961 graduate of Dartmouth and tutor in that second summer, wrote:

A tutor should have a lot of imagination, especially in dealing out punishment. I tried to make the "punishment fit thecrime." If they had lights on after lights out, I took theirlight bulbs; for a pillow fight, their pillows. The boys canunderstand, appreciate, and even enjoy such reprisal.Much of the time a tutor finds himself operating on thebasis of instinct - half-formed impressions, gut reactions.My most important decision of the summer had suchroots, and if I had not had confidence in my instincts, Imight have lost two boys - possibly three.

Almost by reply, one of McCarthy's students wrote in a letter: This summer has been the greatest thing that everhappened to me in my life. As Martin Luther King oncesaid, "Occasionally in life there are those moments of unutterable fulfillment which cannot be completely explainedby those symbols called words." Such is my case. I mademany friends young and old with very interesting experiences, which I know will never be replaced. ...Remember please, if you see Mr. McCarthy, give him theletter and give him a special thank-you. He was the bestfriend anyone could ever have. He trusted me a great dealand I thank him for that ... it gave me confidence.

In August, 1965, William Berkeley left the administrative staff of Solebury School to become assistant director of ABC-ISTS. Two months later, Simmons received another phone call from OEO asking that he come to Washington to serve as acting director for Upward Bound for its first three months. Operating much like ABC, this federal program was to offer a term of summer school for "disadvantaged" students at colleges and universities across the country. When the children returned to their schools during the year, Upward Bound was to provide support services within the home community. After Simmons' departure, Berkeley suddenly found himself directing an ever-expanding Project: A Better Chance with a new development office in New York City.

Mindful of the 300 OEO students, the ABC trustees voted in December to begin negotiations with Carleton College, Williams College, and Duke University to open summer sessions the following year. With a desired maximum of 80 in each program, the five sessions were expected to total 400 boys and girls: 300 OEO scholarships plus 100 Rockefeller and private school scholarships.

Nineteen sixty-six began with renewed efforts to find students and places in the schools. "We were living in airplanes during those times," remembers Bill Berkeley. "It was incredible. We'd fly off in different directions to talk to the kids and their parents and then return to Hanover for a week to find schools for the kids we had just located."

With OEO monies, the young upstart, ABC, had suddenly become a prince as it dispensed $4-5 in scholarship money to every dollar provided by the independent schools, which were originally slated to carry almost the entire load. Despite this aid in funding, the preparatory schools soon decided that they were filled with as many ABC students as they could or wished to handle. Although the Talent Search might convince them to take additional students in one year, it could not expect to find places for the 400 students in each of the following two years.

While Berkeley and the Trustees wrestled with this premonition, Dartmouth initiated a proposal to apply the ABC idea to a public high school. At the urging of Dey and local Dartmouth alumni, a group of Hanover citizens led by school committee chairwoman Elizabeth Bradley proposed to buy a house in Hanover, with room for ten ABC students who would attend the public high school.

Given that public schools like Hanover were significantly better than the schools of ABC students, this new idea incorporated the policy of educational advancement. Beyond that, since the public schools included more introductory level courses than the preparatory schools, it seemed the Talent Search could reach and recruit ABC students who had even slimmer chances of success in their home community. As an added benefit, though not a motivating factor, the exposure of ABC students to middle- class lily-white suburbs and vice versa was expected to develop more appreciation and understanding between races.

Returning from Upward Bound in February, Simmons found the idea of Public School ABC well advanced. By April, a board of directors had been named of respected local citizens committed to the concept of A Better Chance.

To emulate the academic discipline of the private school atmosphere, plans were made to have eight ABC boys live at the ABC house along with a resident-director and his family who would act as substitute parents and directors of the daily operation. In order to strengthen ties with the community and school, it was decided that the resident-director should be a faculty member at the school, that a "host family" would be named for each boy to take special concern for his welfare and include him in family activities, and that two Dartmouth undergraduates would live at the house as resident-tutors to counsel and aid the boys with their problems. Under the original guidelines, every boy was required to complete specific chores within the house follow a schedule of mealtimes and study hours, attend church regularly, hold a part-time job in the community, and participate as much as possible in extra-curricular activities.

The resident-tutors and director would have no easy task in convincing eight "academic risks" - understandably uncomfortable and suspicious of Hanover's lifestyle - to work within those rigorous guidelines to achieve a visionary goal of success, At Dey's recommendation, the Hanover board of directors anpointed Thomas Mikula, a faculty member at Andover Academy, to serve as resident-director for the first two turbulent years. As the math coordinator for the first two ABC summer sessions, Mikula had shown strong dedication to the program and later assumed the job as director of the Dartmouth summer session for the third and fourth seasons. A black sophomore from Dartmouth, William McCurine Jr., was named resident-tutor, and he continued in the job for two years while serving as assistant director to Mikula during those 1967 and 1968 summer sessions.

Meanwhile, 450 students attended summer sessions at Carleton, Dartmouth, Duke, Mt. Holyoke, and Williams, and 432 prepared to enter schools in the fall. And ABC moved its main office to Boston.

In July, the Hanover program rented a residence and proceeded with repairs and renovations for the September arrival of eight ABC students. When school opened, the carpenters and plumbers were still at work. Unfortunately, the lateness of arrangements meant that Hanover received students whom no private school would accept because they were considered the riskiest of the "academic risks." Eventually, the actions of these students, like Beverly Love and Jesse Spikes, would reflect the basic validity of the public school concept.

The first fall of the closely-watched program included a full measure- of challenges and dissatisfactions with just enough gratifying progress to make it worthwhile. Dey was named Dean of the William Jewett Tucker Foundation at Dartmouth, a semi- autonomous department charged with furthering the moral and spiritual work of the College community. Under his leadership, the Tucker Foundation immediately adopted the public school program which had no formal link to the private school Talent Search. In this way, Dartmouth enlarged its contribution to ABC by providing more financial support and accepting responsibility for the new venture.

At the Hanover residence, one student left early in the fall, and several others threatened several times to follow. Despite this dissension, the overall achievements of the boys in academics and school activities indicated great potential for the new idea. Plans were made to open a second public school program in Andover, Mass. - a "test community" that had no large undergraduate body to overshadow the presence of an ABC house.

That winter, OEO decided to take the funds slated for ABC and use them in its own Upward Bound programs. After much debate, OEO agreed to provide 50 scholarships for Upward Bound students within the ABC program, a small consolation next to the promised 300. Also, during this period, the U.S Office of Education terminated its five-year research grant.

The prince had become a pauper.

ABC quickly scrambled to find private funding to save as many places as possible, particularly the public school programs which looked to be left high and dry. By this time, street academies, drug programs, tenant groups, and endless other social welfare organizations were competing for the philanthropic dollar.

Bill Berkeley became executive director of ABC and Garvey Clarke '57, its development director. Along with Dey and Mikula they successfully answered the questions posed by the private foundations. Why give money to a program that works with a few hundred kids, has a high cost per student, and whose impact is long-range? Says Berkeley:

In those early years, everyone felt you could lick theproblem of unequal opportunities by pouring in a greatdeal of money over a few years. Pretty soon, they began tosee that huge sums of money had been spread too thinlywith nothing accomplished. ABC dealt with a comparatively small number of kids, and our costs were high.But as time went on, people began to see that you couldn'tpatch up the education system with home support servicesor even extensive summer programs. To prepare a kidfrom a poor educational background for college, you hadto use a full-time, long-range program that was going totake tremendous amounts of money and take a great dealof lime. In the late sixties, people began to accept this.

Though ABC eventually would raise significant funds from foundations, precious time was needed to mobilize the fund raising support. In the meantime, from the previous summer's high of 432 students, ISTS placed only 288 in 1967. Here a good deal of credit goes to the independent schools for, if the drop in students had reflected the true drop in funds, less than 100 students would have been placed. The private schools increased their support such that the earlier funding ratio was reversed and preparatory schools contributed $4-5 in scholarship aid to every dollar that ABC-ISTS secured from outside sources.

As the Andover residence opened in the fall, groups organized in Lebanon, N.H., and Hartford, Vt., to begin ABC public school programs. Reflecting the growing social conscience in students' minds, the Dartmouth freshmen voted as their Class of 1971 project to staff and support the Lebanon ABC house with tutors for ail four years at college. Dean Thaddeus Seymour called the results of that referendum "the most inspiring single event of the year."

One member of that class, Duane Bird Bear, a Mandan from South Dakota and former tutor at the Hanover residence, decided that even more should be done. He proposed to Dean Seymour: "If the college wants to fulfill its commitment of giving Indian students a complete education and subsequently reduce the attrition rate, then it must do more than trust to its admission procedures and hope the qualified students will get a degree."

These words came at a time when ABC administrators felt increasingly discouraged about the lack of success with Native Americans in the program. Whereas 90 per cent of the blacks who entered summer sessions graduated from their secondary schools, only 60 per cent of the Indians made it to graduation. ISTS was dissatisfied, but when the federal Bureau of Indian flairs heard of the 60 per cent figure, they asked why ABC was so successful.

Largely through Bird Bear's initiative, the public school program in Hartford, Vt., was conceived and organized as a residence for American Indians. To fill the house, a group of 11 Native Americans were included in the 102 students for the 1968 summer session, and Bird Bear acted as tutor to prepare them Socially and academically for the Hartford schools. He remembers, "That summer, we had a fine staff that was particularly dedicated, and we held strong hopes that this would be the answer to the high drop-out rate."

As assistant director, Bill McCurine did most of the planning and organization while Tom Mikula prepared to organize Public School ABC and begin a full-time effort to establish such programs throughout the country. Soon he found that the process opening public school programs included a torturous succession of suggestions, challenges, arguments, and rebuttals.

Through a contact in a middle-class town, Mikula usually tried to interest a small group of influential citizens in the concept of ABetter Chance. Achieving that, he helped the small group inform the entire community about ABC to prevent later charges that the idea had been foisted on the town. These efforts generally included public meetings with talks by ABC administrators, instructors, and resident-directors. After forming a board of directors of local citizens, the prospective program would seek a tuition waiver for the students from the school board and then search for a proper house. If all went successfully, the local program could incorporate and arrange to meet its third of the financial costs with the Tucker Foundation assuming the rest.

Plans usually snarl over the location of the residence whichoften involves a zoning variance to allow the non-related"ABC family" to live together [says MikulaJ. Racial over-tones start to show. We can break down all the oppositionby showing our goals and how we meet them in other communities but then the opponents stand up and say: "It's agreat program. I don't oppose the idea, but. ...”

What can they say with that "but?" They can say thatwe're lying when we say that the kids will study three hoursper night and that there won't be much noise. Or they cansay that they just don't want blacks or Indians or SpanishAmericans in their community. If the opponents of ABCare organized and articulate, we're in trouble.

Often, that's where Public School ABC found itself.

In spite of such opposition and funding troubles, Project: ABetter Chance expanded as the Lebanon and Hartford houses opened in the fall of 1968 and ISTS included over 100 member schools. Given a year's lead time, Mikula organized six public school programs with places for 70 students to begin in September, 1969, while Dey led the fund raising efforts.

In June, Hanover would finish its third year as the oldest program with half of its graduates on the honor roll and all admitted to a college or university. Meanwhile, Bill McCurine directed the 1969 summer session, the first black and first undergraduate to fill the position.

From 55 boys in 1964, McCurine had to organize a six-week session for 169 students, twice what was once considered the optimum number. A Bridge Program for 22 students about to enter college or senior year in high school was to run simultaneously in the hope that they would act as role models for the ABC students. Instead, they proved unruly and had the opposite effect. Within the ABC student body, 48 boys were to attend on the promise that they would be placed in a public or private school if they did well, but without a definite acceptance and a school to consider their own. Another 24 students were north country boys who would "associate" with the ABC house in their hometown during the coming year. Also, the student body was to include 34 Indians, 41 whites, and 94 blacks and Puerto Ricans. This was not an unusual racial mix except that for the first time ABC chose to confront the racial differences through an American Studies course which exacerbated racial tensions. Previously, ABC had concentrated almost solely on reading, math, and English courses. Added to that would be frictions between the undergraduates on the staff and professional teachers.

Still, the summer might have gone well if the mood of the nation and the incoming ABC students had been conciliatory. Instead, it was downright hostile.

Watts had exploded in 1965, with major riots in Chicago and Cleveland the following year. February, 1967, brought the Kerner Commission report on civil disorders: "What white Americans have never fully understood - but what the Negro can never forget - is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it."

That summer produced worse racial strife in Newark and Detroit, but even that was dwarfed by the violent reaction to the murder of Martin Luther King in April, 1968. Major disturbances occurred in more than 125 cities in 28 states.

Parallel to the increase in urban violence, the movement of student militancy had grown from its birth in the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley. Campus unrest and racial disturbances led each other through the mid-sixties while the country's expanding involvement in Vietnam became a further rallying point. In 1968, the Afro-American Society and Students for a Democratic Society at Columbia occupied five university buildings proclaiming solidarity in their quest for black rights and student rights.

Hanover, New Hampshire, had remained pastorally oblivious to the militancy of these movements until 1969. Charles Dey remembers the time: "The growth of black power and black consciousness produced a questioning attitude about the motivations of whites in all programs like ABC. White student militants called ABC another example of 'phoney white liberalism,' just another little something to placate the have-nots. They encouraged the blacks to prove their blackness by dumping ABC as the white man's program."

From the Afro-American Society came charges that A BetterChance co-opted potential black leaders by removing them from their people and placing them in white schools in white communities. In this way, the black graduates produced by ABC were said to adopt a white, middle-class success ethic which denied their true identity as black people. It was the theory of the Oreo - black on the outside, white on the inside.

This situation produced enormous pressures on people like Bill McCurine who tried to straddle the world of elite white colleges and prep schools and the black student movement.

Beyond charges of co-opting black leadership, ABC wasalso criticized for making only a token effort [McCurinesays]. At that time, the total program had involved about2000 students which did not seem like much when you consideredthe size of the plight of black people. I certainlyagreed with that argument, but I was also tutoring at theHanover ABC house, and I couldn't just turn my back onthose individuals saying that they were insignificant innumber. ... As I planned the summer session during mysenior year, I became very embittered about the racialsituation in the United States. My classmates were criticizing the concept and tokenism of ABC, and I became moreand more hostile toward the program while I was director.

In this highly-charged emotional atmosphere, McCurine sought undergraduate teachers and tutors for the summer. Watching the recruitment process, Mikula felt that blacks were accepted far more readily than whites simply for the sake of their race. On this point, Del Benjamin wrote in his master's thesis: “Thinking first of the [ABC] students and remembering how they followed the undergraduates, it might be said that the 1969 summer program was too black; perhaps in 1964 and 1966, they weren't black enough."

In any case, some of the undergraduate staff chosen during that fall and winter were uncommitted to the goals of ABC, resentful of white authority figures, and certainly suspicious of the middle-class values espoused by the program.

A week into the summer program, Bill McCurine resigned, and he looks back critically on that action. "Motives which I nought then were noble and self-sacrificing and smacked of a pleasant revolutionary spirit were actually very narrow-minded, even cowardly. But those realizations did not come until I was a year and many miles away from the 1969 summer session."

Several tutors were uncooperative and undedicated; many ABC students doubted the value of the program; most of the Bridge students raised hell, and undergraduates and professionals on the faculty were not communicating. It was no time for a white, middle-aged male to tell anyone what to do, but volunteers were scarce and time was short. With fingers crossed and a short prayer, Tom Mlikula became director, and ABC slugged through "that terrible summer" at Dartmouth and sent the kids on to 12 public schools and 48 private schools across the country.

from Stanford, Jim Simmons saw the rise of black consciousness and hoped ABC would respond positively to the movement:

The original idea of integration was a one-way street.White America was saying it would accept blacks as longas they came in just like the whites. That is, blacks had togive up things characteristic of their blackness - dress,hair style, music, gestures - in order to be accepted byWhite America, which did not propose to give up anythingin the mixing of the two peoples. In the late 1960s, theblack kids were saying that they were not going to do liketheir fathers and grandfathers did. They were not going todeny or be ashamed of their own culture. If there's going tobe any integration, then it's going to be a two-way streetand we re both going to acknowledge each other's culturaldifferences. ... When the black kids came to colleges inthe late 1960s, they arrived without the guilt and hang-upsof the previous token blacks. They were willing to assertthemselves and demand recognition of their blackness foritself

When the independent schools made a significant commitment to ABC and accepted enough minority students to create an identifiable non-white community, conflicts arose over institutional change. Some headmasters foresaw the needs of these students and provided for Afro-American societies, black studies courses, and other avenues of cultural awareness. But whether the innovations came grudgingly or agreeably, strong conflicts inevitably surfaced.

As a Morehouse College trustee held captive when a board meeting was taken over by blacks, Charles Merrill recalls:

The black students were constantly pushing and probing tofind weak points and test our sincerity. They wanted to findout just how much they could trust these white liberals, andthe problems and pressures became terrible. ...

You got the conflict between the white kids and blackkids because the blacks could break rules and the whitescould not break rules. On the other hand, blacks felt thatwhen black people broke the rules, they were punishedmore severely than white people would have been. And it'strue that headmasters tended to be more careful in dealingwith white kids whose parents usually had some sort ofprestige or money. The black parents were often afraid tospeak to the white power structure, and when a black gotinto trouble, it was easier to be strict since he was usuallyalready on academic probation and receiving a 90 per centscholarship. That in turn was dishonest because we keptblack students in the school on academic or personaltrouble much longer than we kept white students.

I finally came to believe that it is a dishonest gameplayed dishonestly by both sides in which you eitherstomach the trouble, get rid of the students, or leave.That's why I take sabbaticals as often as possible. ... ButI still let the students know that we were in this for good;the school was either going to service bi-racially or die.

An economic depression in the private school world further complicated these problems. Applications dropped, costs rose, and more students required financial aid. On a national seals, the ABC-ISTS annual report declared 1969-1970 the worst year yet for fund raising. Government agencies on all levels cut back funds, and most educators agreed that the new Nixon administration was not outstandingly receptive to programs like A BetterChance. ABC once again heard the criticisms of its high cost-per-student, low enrollment numbers, and emphasis on secondary school. Meanwhile, the charges of co-opting minorities, tokenism, and a bourgeois ethic mounted from students and onlookers. In between sat the white educators who had started the program with high hopes and were catching hell from all sides.

“We were left scarred by that period," says Headmaster Michael Choukas '51 of Vermont Academy, a charter member of ISTS. "I wish someone could have pushed a button just after the blacks learned to be proud of their race and just before the violence. If someone could have foreseen that movement and guided it so as to have avoided the excesses, we might be much further along right now. But perhaps the militancy was necessary for them to be taken seriously."

As the new decade began, ABC discovered the drawbacks of its rapid growth. Recruitment had lost a personal touch, for the ISTS depended more on secondary resource people to locate students. To reverse this and relieve any stigma that students might feel in coming from "deprived backgrounds," the Tucker Foundation suggested that ABC designate specific localities of concentration and introduce private school students to the com- munities of the ABC classmates. In 1970, Dartmouth offered the resources of its Learning Center in Jersey City, N.J., to match ten urban ABC students with ten suburban students from VermontAcademy. All twenty enrolled in a full-year schedule to study the inner-city environment, specifically related to Jersey City. Aside from normal classroom work, the project included week-long trips to the city to examine urban life and problems.

simultaneously, ABC tried to increase the "risk factor" in admissions by accepting applicants with seemingly less chance for success. The criteria changed to where students in the 1964 summer session would have generally been rejected as "over-qualified" in 1970. Applicants rejected as "too risky" by mid-sixties standards were being sought five years later.

In the public school programs, the ABC students endured at least a few taunts and racist provocations. As resident-director in Hanover. Del Benjamin found that "the students felt like they encountered a lot of bigotry in the town. I thought they were received warmly by most people, but it takes only a few instances of rejection for a young person to feel that he has been rejected by many. ...”

Miguel Cardona '74, a former ABC student in Lebanon, later a resident-tutor, and then assistant summer director, says:

Some people used to call me names and curse me when Iplayed on the soccer and basketball teams, and there wasone fight with a Lebanon student. But I ignored it ingeneral because almost all the people accepted me verywell. ... I arrived in New Hampshire from Brooklynthinking all whites were bad, but I began to see I waswrong from the people I met. My host family in particularwas really good to me.

By this time, the public school "experiment" had spread from New England to the Midwest, a total of 22 localities with five more to open the following year. Through the Tucker Foundation, Dartmouth still had responsibility for the financial and educational success of the entire network - locating capital funds, administering the organization, finding directors and tutors. Due to this growth and future potential, it seemed proper that Public School ABC leave the Dartmouth umbrella and join ABC-ISTS. However, ISTS was struggling with its own financial and development problems and could not absorb a totally different set of challenges in this new sector. Public School ABC thus incorporated on its own with Mikula as executive director. He continued to rely on Dartmouth alumni and friends across the country who had in some way initiated practically every public school program to that point.

Early in 1971, A Better Chance - Independent Schools Talent Search and National A Better Chance Public School Program made definite plans to merge and so join their development efforts. In terms of the strata of available philanthropy in the country, the programs had long passed the first level of major foundations and were then exhausting their options in small family foundations. In the government sector, federal funds were cut back, although ABC did enter contracts with local Model Cities agencies for their students and some local and state governments to provide an education for promising state-dependent children. Beyond those areas, a potential source lay in corporate foundations as American business began to perceive its obligation to the society which supported it.

As ABC faced these decisions introduced by the program's growth and financial constraints, a positive sign of the seven years maturity was that non-whites, and, more particularly, ABC graduates had entered administrative levels of the program. Simultaneously these people faced pressures from their own racial and ethnic groups through the continuing allegations of cooperation with white society.

Private school headmasters had long observed that some of their most brilliant ABC students hesitated to succeed, for it meant success within that elite prep school system leading to possible rejection by ABC classmates or hometown friends. Similarly, criticism was directed at people like Del Benjamin who continued to participate through personal dedication:

You know, some of us really believed those ABC manuals,and I guess I was one of them. I saw ABC as a program tohelp young people - to take them out of situations wherethere were insurmountable problems and place them in anew situation where there certainly were great problemsbut ones that the student had a chance to overcome - especiallywhen we provided individual support. ... Otherpeople see ABC as something different and bad. and thusthere are charges against those who work with ABC. But Ifelt the program was justified and, more than thatnecessary.

June, 1972, brought special vindication for those at ABC as two public school "academic risks" of 1966 graduated from Dartmouth College. Beverly Love entered medical school, and Jesse Spikes went to England as the first ABC Rhodes Scholar.

ABC-ISTS and Public School ABC had completed their merger to form A Better Chance, Inc. with the head office in Boston, development office in New York City, governmental affairs office in Washington, D.C., and public school program office in Hanover. Six regions of concentration were designated: Northern New England, Eastern New England, Mid-Atlantic, New York City, Midwest, and West Coast. William Berkeley continued as President, and Charles Dey as Chairman of the Board of Directors.

By September, after the ninth summer, ABC participation had increased eleven-fold from the 55 students in 1964. Nation-wide, the entering 1972 class of ABC included 626 students enrolled in over 100 private schools and 27 public schools. Of particular note was the opening of the first all-female public school program in Wellesley, Mass., with a Harvard law student as resident- director: William McCurine Jr.

After the merger, public and private schools jointly faced the growing problem of providing for Native Americans within the program. By 1972, Duane Bird Bear, earlier one of the most ardent supporters, had become one of the most outspoken critics ABC. Said Bird Bear:

I think Indians feel a kind of patronizing racism from thepublic school communities in being looked at like the "noble savage." When we set up the program in Hartford, Iremember one local citizen saying to me: "I'm sure gladwe got an Indian house here because we could never get anall-black house in this community." That seemed to mepretty hypocritical because they would accept Indians whojust didn't seem quite as threatening as blacks.

Based on such arguments, two Indian researchers produced a report in 1973 to the Federal Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) recommending that it no longer fund reservation students in the ABC program. Feeling that statistical evidence was neither obtainable nor indicative of the problem, these researchers concluded subjectively that ABC siphons off Indian leaders from the tribes and acculturates them by severing ties with the home community. Trudell Guerue Jr. '74, a Sioux from South Dakota and ABC student in 1964, disagrees: "An Indian is an Indian and will remain so. ABC may provide a better access to outside society, but if someone is going to leave the reservation for good, then he will decide that long before he gets involved with ABC.”

Such words often left the speaker open to charges of "not being an Indian." Parents and tribal elders have been greatly enthusiastic about A Better Chance, while younger Indians have often challenged the program.

The idea of the public school program has also been questioned. Larry Bagley '73, a black ABC graduate of Milton Academy who has worked two summers as a resident-tutor, and now is the fuli-time ABC recruiter of the Dartmouth Learning Center in Jersey City, states:

In the private school, the rules are made jor everyone andapplied equally to everyone within the school. In the publicschool program, the students feel isolated by the specialrules which do not apply to others in their peer group. Thiscreates a conflict in the student which causes problems inthe house. Instead of putting the money there, perhaps weought to be building prep schools in the communities.

To these arguments, the people at ABC often react with frustration. ABC is swamped every year by more applicants than It can possibly place, and the achievements and gratitude of the students leave little motivation to cut back the opportunities.

In 1972, George Perry, ABC researcher, completed the results of his two-year study of ABC students. He concluded that the ABC experience raised the student's self-esteem, aspirations, and sense of being able to control his own fate. Perry also found attitudes which seemed to refute the argument that A BetterChance co-opted its students into white society:

Like students in other studies of integration, the attitudes of ABC students become somewhat more "separatist" as aresult of experiencing prejudice, culture shock, and gaininga greater sense of pride in their own background. Theytended to develop more integrated behavior, spendingsomewhat more free time with whites and having morewhite friends.

In terms of academics, Perry reported that 80 per cent of the 3,339 students who entered ABC graduated from their new secondary school, and 99 per cent of those entered college. In a controlled study of 50 pairs of students of matched abilities, one of whom entered ABC and one who did not, it was found that 62 per cent of the ABC students graduated from college, compared to 31 per cent of the non-ABC group. A Better Chance thus maintains that about twice as many of its students make it through college than otherwise would have graduated.

Perry found that about half of the ABC college students enter better colleges than if they had remained at home. Also, 40 per cent of the ABC college graduates have entered graduate school, many of them quite prestigious ones. In this respect, the ABC staff expects the long-range effect of the program upon its participants to ever increase as the individuals embark on careers.

Aside from the statistics and conjecture, Tom Mikula views the program on a personal level:

I maintain that guys like Jesse Spikes and Beverly Laveare worth all the trouble and all the money you put into it.There's a Rhodes Scholar and potential doctor who mightnever have made it out of their hometowns if they hadn'treceived some extra help along the way. They're going toreally serve their communities, and nobody around herewas sure they would make it through Dartmouth. We underestimated their talent. I don't think anyone else wouldhave picked them out from their home communities. ...

It makes me angry to hear people say that we're doingmore harm than good with these kids. ... In that troubledsummer of 1969, we had a black student from Portsmouth,N.H. His tutor was one of those doing a terrible job withthe kids and cutting down the program. Halfway throughthe summer, this student got fed up and decided to leaveABC. If it had been the summer of 1968 or 1970, we mighthave done something with that kid, but there was so muchupheaval we couldn't reach him in 1969.

Two years later, I saw his picture on the front page ofthe Boston Globe - indicted for murder in the shooting ofthe mayor's aide in Boston. Arnold King was his name. ...

In 1973, while the tenth summer approached and the economy tightened further, ABC found that as a far-flung but thinly-spread network it did not have enough personal contact with the students. The main office decided to concentrate impact in specific areas, increase support services for students, and facilitate funding of the scholarships. ABC felt it would have greater leverage in obtaining a city's philanthropy to support hometown students, and that recruiting and follow-up would be far easier with a dependable network of resource persons who knew ABC well. The reorganization produced the Target City concept: recruiting students from specific urban and areas rather than the previous 40 states.

Seeking these benefits, ABC organizations incorporated in Cleveland, Columbus, New York City, Philadelphia. Pittsburgh, Washington, and Twin Cities, Minn. A number of places were also reserved for Native American students, Jersey City students, and rural Southern students who have particularly excelled in the program.

With influential citizens on the board of directors, an organization like Cleveland ABC, Inc. was expected to raise funds for its 50 scholarship students, recruit them, provide orientation programs and organize reunion activities to ensure a sense of continuity and partnership in the larger effort. Meanwhile, the national and regional ABC offices matched students and schools, offering advice, encouragement, and support as the inevitable problems arose.

Local Model Cities agencies made threatening noises in 1973. It appeared that the federal government was hoping to pare down the next-to-last year of Model Cities funds and eliminate the final year. Suggestions of dropping ABC scholarships brought hurried conferences to try to dull the axe. At the same time, independent schools reduced their scholarship funds when prices soared and resources dropped.

You have a certain number of dollars to spend on financialaid, and you have to figure out how you are going to do themost good for the most people [says Howard Jones], Thedifficulty is that you can get two or three middle-classwhite students, who cannot otherwise afford the school, forthe same dollars that bring in one black or Chicano student.At the same time, it's more expensive to educate theunderprepared minority student who usually needs morecounseling and attention than the middle-class student.

Then when we started bringing in Native Americanstudents, the black students objected that this was detracting from their allotment of funds. That was true but wewere also hearing from white alumni and parents who werecomplaining that the blacks were taking all theirscholarship money. ... Now the Trustees have reduced thescholarship budget by $100,000 to make ends meet.Meanwhile, people keep asking us: " Why aren't these kidsmore grateful?"

Aside from the security of money, the public school program was flunking test after test in white communities. Although more than a hundred Dartmouth alumni from Altadena, Calif., to Lower Merion, Pa., had worked to introduce ABC to their towns, Middle America refused to welcomed Better Chance. From the classes of 1921 to 1972, in cities, towns, and suburbs, alumni received the same cool response in these critical years. The 1971 Public School ABC annual report optimistically suggested that "we would be able to establish as many as twenty new public school residences by September of 1972."" This was later scaled down to a goal of ten, and five were eventually opened. The same goal in 1973 brought three new programs. Despite Mikula's persistent and exhausting efforts, ABC was running out of the college towns and private school communities.

Friends of ABC reached the discomforting consensus that Americans felt that blacks and Puerto Ricans had had their day in the 1960s, that enough money had been spent and it only produced riots, that things might even improve if America benignly neglected lower-class minorities. More succinctly, in Bill McCurine's words, "People are busy looking for The Good Life,' as they say in the television commercials."

In 1962, the Gallup poll indicated that Americans considered the racial situation the sixth "most important problem facing the country." By 1964. it had climbed to third and then reached number two behind the Vietnam War for 1966 and 1967. Within two years, it was overtaken by crime and dropped to third. By the beginning of 1972, the racial situation had fallen back to the fifth most important problem behind economy, Vietnam, international problems, and drug abuse. Barry Jones '73, 1964 ABC student, comments, "As it has been for years, racism is still the most important problem in the United States. You can have all the Vietnams and crime that you want, but racism is still the underlying problem that must be overcome before this country can work on other problems."

In addition to these challenges, ABC continues to hear the charges of elitism and bourgeois values implicit in education at a prestige school. Writing in Essence, an ABC student from the 1965 Mt. Holyoke session asked:

What do you do with a dream house whose time haspassed? Should there be programs like ABC, UpwardBound, and the College Bound whose goals are admittedlyelitist in orientation? ... The "golden opportunity" concept of ABC has been reduced as students realize it ispossible to get into Radcliffe without a private schooleducation and do well there, while others are evenquestioning the need to go to a Radcliffe.

Del Benjamin offers one justification: "ABC has chosen one battlefield to fight on and should not be rejected because of where it chose to fight. This was a vacant battlefield which no one else had entered. ABC took up the fight successfully on that ground and wishes all other programs success in their chosen battlefield as well."

After ten years the score on the battlefield speaks for itself.

A decade after the first summer session, in June 1973, 39 boys and 16 girls arrived in Hanover for a three-week session at Dartmouth College.

While Jesse Spikes and Beverly Love finished their first year of graduate school, the 13 blacks, 23 Native Americans, 1 Chinese, 3 Spanish-Americans, and 15 whites unpacked their belongings and assembled for an orientation meeting.

As 1,371 ABC college .students closed their books for the academic year, these new students were told, "From this moment, for the next three weeks, you're on ABC time. That's when every minute counts. Every five minutes you waste is part of your education down the drain; you ought to remember that."

“When your tutor says to be some place at 7:30, you be there at 7:30 sharp, not 7:35 or 7:33. We want you to feel loose and comfortable but also to take care of business. That's why you're here and don't forget it."

Reflecting on the recent summer programs, Charles Dey says, “The new directors are now emphasizing the strict discipline that started with. It's like we're in a cycle." “... like a cyclical process," believes Tom Mikula.

True enough, except that the 1973 director wore an Afro instead of a military crew cut, and his assistant was a Spanish-American from New York City rather than a white college administrator. Through that transition, A Better Chance finds its Own justification.

Charles Dey '52 (left) and James Simmons. Dey, fresh from thePeace Corps, took over the first ABC summer program. Simmons, who recruited the first ABC students, later heard SargentShriver say of $10 million: "That doesn't scare me."

These 12 students posed outside the Andover ABC residence, second established in the nation. "I don't oppose the idea, but. ...” was a familiar refrain heard in other locations.

Thomas Mikula, who picked up the pieces in the "terriblesummer" of 1969, now is head of the national ABC program.Here he talks with tutor Bill Mansker '71 in Baker Library.

Homework in the Woodstock, Vt., residence (from left): RussAkers, later Class of 1976, tutor Bill Engle '71, resident tutorBill Yellowtail '69, and James Roscelli.

An evening conference in the Hanover house (from left): BenBaker, Beverly Love '72, tutor John Briganti '69, Bill McCurine'69, head of the 1969 summer program, and Steve Steward.

Stalag 17 that first summer: "They hated the idea, wouldn't learn lines," recalls an observer. "In the end, they were great.”

Marcia Brown was among the first group of young women inthe Hanover program. She went on to study at Stanford, andlater joined the Black Muslim movement in Washington, D.C.

Scenes in Jersey City: a demonstration of youthful machismo on a front stoop; Dartmouth students teaching in a public schoolclassroom; and first confrontations with the computer.

Scenes in Jersey City: a demonstration of youthful machismo on a front stoop; Dartmouth students teaching in a public schoolclassroom; and first confrontations with the computer.

Scenes in Jersey City: a demonstration of youthful machismo on a front stoop; Dartmouth students teaching in a public schoolclassroom; and first confrontations with the computer.

For most students, ABC was - and is - a combination of isolation and comraderie, hope and despair, success and failure.

ABC students tour Main Street, Hanover, in the first summer,ten long years ago. It has been "like a cyclical process."

Bruce Kimball, Class of 1973, took part in the Tucker Foundation Jersey City project as an undergraduate. A journal of his experiences in Jersey City appeared in the November 1971 Alumni Magazine. He is now a student at Harvard Divinity School.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIn language teaching, a call for ‘madness'

February 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

February 1974 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleLatter-day Koster Man

February 1974 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

February 1974 By JACQUES HARLOW, ERIC T. MILLER -

Article

ArticleHEINZ VALTIN

February 1974 By Andrew C. Vail Memorial, R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1974 By DREW NEWMAN ’74

Features

-

Feature

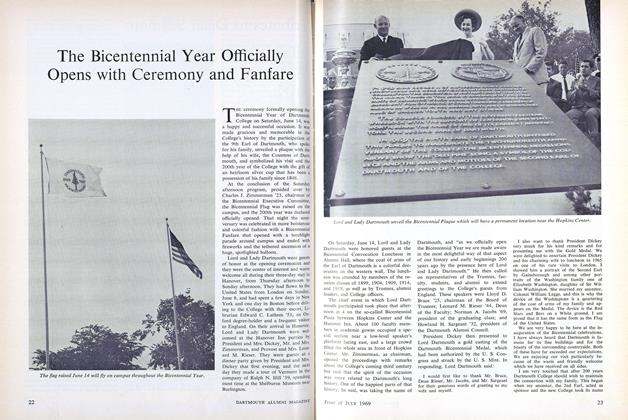

FeatureThe Bicentennial Year Officially Opens with Ceremony and Fanfare

JULY 1969 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHot Seats

April 1981 -

Feature

FeatureThe Gatekeepers

Nov/Dec 2002 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

Feature"THE KINGDOM OF GOD HAS COME"

October 1974 By MARy BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

Feature"He could Have talked Satan into abandoning hell"

March 1975 By MARY BISHOP ROSS