John Humphrey Noyes' pronouncement in 1837 was greeted, he said, by "a sublime clap of thunder." It also produced earthly rumblings as Noyes founded the Oneida Community on the radical rock of Bible Communism.

HENCEFORTH, he declared, he was free from sin, in a word: perfect. In a mystic revelation, "Joy unspeakable and full of glory filled my soul. All fear and doubt and condemnation passed away. I knew that my heart was clean, and that the Father and the Son had come and made it their abode."

In 1834, with revivalism sweeping the land and exhortations to repent booming from pulpits in every city and hamlet, cries of "madman" and "handyman of the Devil" greeted this claim of eternal salvation already accomplished. Such heresy from the lips of John Humphrey Noyes, an 1830 Dartmouth graduate by then a Yale theological student, resulted in his separation from the seminary and the revocation of his license to preach. Noyes' protest that "I do not pretend to perfection in externals. I claim only purity of heart and the answer of a good conscience toward God" was to no avail.

Banishment from traditional pulpits left him unabashed: "I have taken away their license to sin, but they keep on sinning. So, though they have taken away my license to preach, I shall keep on preaching."

Not only did John Humphrey Noyes continue to preach his doctrine of Perfectionism throughout a turbulent lifetime that ended more than 50 years later in Canadian exile, but he set about establishing the Kingdom of Heaven on earth, first in Putney, Vermont, and then in Oneida, New York. With a devoted and burgeoning coterie of followers, he was shortly to found communal societies which would include the most radical experiments in human relations ever practiced in the United States.

Of all the Utopian schemes which grew out of the religious and social ferment of the mid-nineteenth century, it was the Oneida Community, with its early Vermont predecessor, that put its philosophy of communal ownership and communal living most thoroughly into practice and lasted the longest, surviving its better known counterpart, Brook Farm, by more than 30 years. Where Brook Farm, an agricultural community supported by the Boston Transcendentalists, foundered on financial seas after five years, the Oneida Community, consolidated from the refugees of Putney and a small group of Perfectionists in central New York State, grew, diversified, and prospered until 1880, when the common property was converted into a joint stock company, Oneida Community Ltd. Its present-day successor, Oneida Ltd., with current assets of over $70 million and subsidiaries in five countries, is still presided over by Pierrepont T. Noyes, 60, grandson of John Humphrey.

To say that Noyes was a man ahead of his time is an understatement as monumental as the personality and inluence of the man himself. He was appalled by the oppression of women and their relegation to kitchen and nursery before Feminists were heard of. He in stituted systematic programs of continuing education for adults before the first state made schooling of the young compulsory. He counseled, with demonstrable effectiveness, a method of birth control that would make Zero Population Growth adherents seem like advocates of the biblical dictum "be fruitful and multiply." Abhoring the nuclear family as idolatrous and decadently romantic, he established communes with a life style that the most radical of today's young social philosophers would hardly think to emulate. He and his followers participated in a scientific program of selective human breeding before the word "eugenics" was coined. He anticipated group therapy by a century with a practice he called "mutual criticism."

Son of the Honorable John Noyes, a Vermont Congressman and a Dartmouth graduate in the Class of 1795; first cousin of Rutherford B. Hayes, 19th President of the United States; uncle by marriage of William Dean Howells, John Humphrey Noyes entered Dartmouth with the unexamined assumptions of a conservative young Vermont aristocrat and a casual approach to religion. After graduating Phi Beta Kappa, he read law in the office of his brother-in-law Larkin Mead until conversion at a revival meeting led him to dedicate his life to God and to enter Andover Theological Seminary. Disillusioned by what he regarded as rampant hypocrisy and materialism at Andover, he transferred to Yale in search of more genuine religious fervor. New Haven did indeed seem more enlightened, but it was his association with the Free Church rather than the influence of the Yale clerics that brought the young man to his heretical announcement of his immunity to sin.

Noyes' Perfectionist doctrines were forged from his ultimate rejection of the tenets of both the orthodox churches - which he was convinced had fundamentally misinterpreted the Bible - and of the radical theologians of the day - which he found wanting in many respects. From his own study of the New Testament he concluded that the Second Coming of Christ had already occurred in 70 A.D., at the fall of Jerusalem, and that therefore the establishment of the Kingdom of Heaven on earth and man's freedom from sin - his perfection - were both theologically possible, once he was reconciled with God. "A pure heart and its counterpart, a good conscience (which is all we mean by perfection)," Noyes wrote, "are inward matters, which may be produced instantaneously by the infusion of the purity and good conscience of Jesus Christ, and are independent of external conduct - though necessarily productive, more or less, of outward righteousness." The attributes of man thus reborn into the world of the spirit, he believed, were a renewed mind, a loving heart, and an unending quest for spiritual improvement.

Mail's sorry state, according to Noyes, stemmed from four sources: his estrangement from God; the dislocation of the relation between the sexes, of which women were the primary victims; oppressive labor, which worked mainly to the detriment of men; and death, evils which only a return to the principles of the Primitive Church - "the original organization instituted by Christ and the Apostles" - could alleviate. Furthermore, selfishness, the basic sin of the outer world, was inherent in two fundamental structures of contemporary society: exclusive marriage, which bred lust, jealousy, and the subjection of women; and private ownership of property, which rewarded greed, acquisitiveness and oppression of one's fellow man. With these two institutions abolished under Bible Communism, man could once again communicate with God and the reformation of the industrial system and victory over death would naturally follow.

For several years after he and Yale parted company, Noyes preached and published his theories, first in The Perfectionist and later in The Witness. In 1838 he returned to his father's home in Putney, determined to make them a way of life. "Religion is the first subject of interest and sexual morality the second, in this our great enterprise of establishing the Kingdom of God on earth," he wrote.

To Miss Harriet Holton, granddaughter and ward of a former Vermont lieutenant governor and member of Congress, herself already an avowed Perfectionist, he proposed "a partnership which I will not call marriage until I have defined it."

As believers [Noyes said] we are already one with each other and with all saints. This primary and universal union is more radical and of course more important than any partial and external partnerships, and with reference to this it is said, "There is neither male nor female," "neither marrying nor giving in marriage" in heaven.... Therefore we can enter into no engagements by the fashion of this world. I desire and expect my yoke-fellow will love all who love God, whether man or woman, with a warmth and strength of affection which is unknown to earthy lovers, and as freely as if she stood in no particular connection with me. In fact the object of my connection with her will be not to monopolize and enslave her heart or my own, but to enlarge and establish both in the free fellowship of God's universal family. If the external union and companionship of a man and woman in accordance with these principles is properly called marriage, I know that marriage exists in heaven, and I have no scruple in offering you my heart and hand with an engagement to be married in due form as soon as God shall permit.

To which extraordinary suit, the imperturbable Miss Holton replied: "In gladly accepting this proposal for an external union I agree with you that it will not 'limit the range of our affections.' The grace of God will exclude jealousy and everything with which the marriage state is defiled as we see it in the world."

The wedding took place within three weeks, on June 28, 1838, Queen Victoria's Coronation Day, and Noyes moved with his bride into his father's house. Their honeymoort was a trip to Albany to purchase a second-hand printing press, an investment made possible by Harriet's generous dowry, which permitted them also to build a fine house within the year and provided their support for six years. With Noyes' younger brother and two sisters and a few early converts, publication of The Witness was resumed. A free press "to revolutionize the souls of men," the prophet believed, "was destined to supercede the pulpit in the government of the world."

When Squire Noyes, several months before his death in 1841, divided his estate among his children, the almost $20,000 share of his four Perfectionist offspring further increased the financial solvency of John Humphrey Noyes' "great enterprise" of establishing the Kingdom of God at Putney. Even before his father's death, Noyes invested himself with supreme authority over family affairs and proceeded, to his mother's dismay, to arrange marriages between his two Perfectionist sisters and two of his young disciples. As capital accumulated and the membership grew, what had been formed as a society for Bible study and religious instruction moved gradually toward the full implementation of Bible Communism. In 1844 a Contract of Partnership, providing that all property of the corporation be held in common, was agreed upon; the following year a constitution recognizing also the rights of those who invested only time in the community was adopted.

It was 1846 before Noyes deemed the time right to put his theory of complex marriage into effect. In keeping with his belief that "special relationships" between individuals promulgated idolatry, jealousy, and selfishness and that all who followed God were "one with each other and with all saints," he maintained that "in a holy community, there is no more reason that sexual intercourse should be constrained by law, than that eating and drinking should be - and there is as little occasion for shame in the one case as in the other." But, Noyes warned, woe to him who casts off the laws of a sinful society "before he stands in the holiness of the resurrection"; motivated by lust and licentiousness, he was an adulterer.

Before complex marriage became common practice even in a holy community such as Putney, a way had to be found to separate the amative and the procreative functions of sex. The former, Noyes contended, elevated physical love into the life of the spirit; the latter subjected women to the tyranny of continual unwanted child-bearing. During the first six years of their marriage, Harriet had borne five children, only one of whom lived, and Noyes was determined to accept celibacy, if necessary, rather than to inflict further "fruitless suffering" upon her. Male continence, his "great discovery," not only spared women involuntary propagation, but it made possible - first on a modified scale among four discreet and well disciplined couples - the extended family, complex marriage, where all are married to all. To those who objected to male continence as a sinful interruption of a natural act, Noyes retorted: "Every instance of self-denial is an interruption of some natural act. The man who contents himself with a look at a beautiful woman, the lover who stops at a kiss are conscious of such an interruption. Must there be no halt in this natural progression? Brutes, animal or human, tolerate none. Shall their ideas of self-control prevail? Nay, it is the glory of man to control himself, and the Kingdom of God summons him to self control in all things."

Despite Noyes' conviction that external law, presupposing internal depravity, was meaningless for the righteous - "God reigns not by law, but by grace and truth" - the unreconstructed brethren of Putney took a different view. Rumors of scandalous goings-on among the Perfectionists, inflamed by Noyes' claims of conquering death through faith healing - and the conversion of several daughters of the local gentry - stirred the townspeople to rage. Noyes was arrested on adultery charges and took abrupt leave "to prevent an outbreak of lynch law among the barbarians of Putney," he later said. Shortly thereafter, in early 1848, as space could be made for them and their affairs settled in Putney, members of the colony migrated to Oneida, to join a small band of Perfectionists who offered them refuge.

Refugees though they were, these sons and daughters of some of Vermont's first families constituted no "wretched refuse." With their not inconsiderable worldly goods and their unquestioning devotion to the tenets of Perfectionism and the divine inspiration of their leader, the 31 adults and 14 children from Putney formed the nucleus of the Oneida Community, where for 32 years Bible Communism flourished in all its implications.

By the end of 1849, their first communal home, a three-story wooden structure with the extraordinary amenity of steam heat, was built, men and women alike sharing in the labor. Land had been purchased and farms were under cultivation. One of the existing buildings was designated as the Children's House, where youngsters of the community were cared for by men and women specially suited to the trask. By February 1851, 205 members were reported.

Housekeeping arrangements were the same as at Putney. To save kitchen drudgery, only one hot meal a day was served - at breakfast; at other times, food was available at will in the pantry. Unattractive chores were shared by all members of the community in turn. While individual differences in human capability were recognized, and each member was assigned to jobs at which he was most able, all labor was accorded the same dignity.

Since women's dress of the day was considered not only impractical for work, but also as conducive to vanity, what probably were the first "pants suits" were designed by community seamstresses: knee-length dresses in bright fabrics with matching trousers made like children's pantaloons underneath. Long hair was bobbed "since any fashion which required women to devote considerable time to hair-dressing is a degradation and a nuisance." To prevent shock to "outsiders," a stock of "going-away clothes" was kept on hand for the use of men and women who had business to do with what was known to Oneidans as "The World."

Since a renewed mind and a continuing search for spiritual growth were attributes of the reborn man, Bible readings, lectures, and discussions on topics of intellectual interest constituted the major share of the regular evening meetings. But the Oneidans were joyful people who took pleasure in light entertainments as well. Immediately after supper, Noyes' first annual report relates, the community gathered in the parlor, where the first order of business was roll call "not for the purpose of ascertaining the presence or absence of the members (as all were free in this respect) but in order to give each member an opportunity and invitation to present any reflections, expressions of experience, proposals in relation to business, exhortations, or any other matter of general interest that might be on the mind waiting for vent." A typical week of programs: "Monday evening was devoted to readings in the parlor from public papers; Tuesday evening to lectures by J. H. Noyes on the social theory; Wednesday evening to instruction and exercises in phonography [a kind of shorthand]; Thursday evening to the practice of music; Friday evening to dancing; Saturday evening to readings from Perfectionist publications; Sunday evenings to lectures and conversation on the Bible."

Discipline, again as at Putney, was based on a system of mutual criticism, whereby members of the community were encouraged to submit themselves at regular intervals for appraisals of their virtues and vices by the assembly or, later as the membership grew, by a committee of the wisest judges. As Noyes' son Pierrepont wrote in My Father's House, "The committees mixed praise with faultfinding. The essence of the system was frankness; its amelioration friendliness and affection. Yet it was always an ordeal. Without doubt, the human temptation to vent personal dislikes on a victim was not resisted by everyone; yet I have heard old members say that the baring of secret faults by impartial criticizers called for more grace - as they used to say - than the occasional spiteful jab of an enemy."

During the early years, the Oneida Community supported itself by the produce of its farms and the sale of canned goods, handmade travelling bags, and a few animal traps invented by an eccentric member named Sewall Newhouse. By the mid-1850s, the increasing financial needs of a growing population and the costs of publishing Perfectionist periodicals fit neatly with Noyes' long-since-proclaimed aim of reforming the industrial system. The decision was made to expand the community's commerce with "The World," and Newhouse was prevailed upon to share the secrets of trap manufacture with a few trusted apprentices. The venture was so successful that the fortunes of the community were never again in jeopardy. A brick factory was built, output shortly reached 275,000 traps a year, the Hudson's Bay Company bid for all that could be made, and as many as 250 outsiders were hired in ensuing years to augment the work force of the colony. The trap business continued until 1925, when it was sold so that Oneida Ltd. could devote its full effort to the manufacture of silverware, an enterprise which had started on a modest scale only in 1877. The old trap shop, with its upstairs rooms where women of the community processed silk thread for sale, remains a part of the silver plant.

From the start, complex marriage and its contraceptive prerequisite, male continence, prevailed at Oneida. Indisputable testimony to the effectiveness of the latter is the birth of only two children per year to some 40 couples of suitable age, all married to all, during the first two decades of the community's existence. In his evening talks, Noyes sought to eradicate vestigial tendencies toward exclusive marriage, and mutual criticism was employed on those seen as tempted by sinful "special attachment" to any one member of the opposite sex. What were delicately termed "transactions" were arranged through a third party, so that any woman might decline, without embarrassment, the attentions of any man she had not learned to love.

Close relationships between parent and child were viewed equally as idolatrous as "special love" between man and woman. Babies remained with their mothers until they were able to walk, when they were moved to the Children's House, there to progress from room to room under the devoted, though undemonstrative, care of the surrogate mothers and the fathers responsible for their nurture and education. There were lessons and games and play, although toys - like all other material goods in the community - were common property. Friendships which appeared in danger of becoming special - in the vernacular, "sticky" - were broken up by separation; young children were permitted to visit their mothers in their rooms once or twice a week, but unseemly displays of affection were to be guarded against.

With the prosperity of the community insured and the institution of exclusive matrimony successfully abolished, in 1869 John Humphrey Noyes decided the time had come for the most radical social experiment of all: a program of scientific human breeding, which he called "stirpiculture." As early as 1848, he had written "We are opposed to random procreation, which is unavoidable in the marriage system. But we are in favor of intelligent, well-ordered procreation." Animals were bred from the best of stock, he reasoned; why not human beings? And the Oneida Community, already freed from marriage laws and customs of the world, was the ideal laboratory for an experiment in the production of superior human beings. After Father Noyes' explanation of the theory and the plan, 53 young women volunteered to bear children by fathers chosen first by Noyes and later by a committee of elders; 38 young men offered themselves "to be used in forming any combinations that may seem to you desirable."

During the stirpiculture decade at Oneida, 58 children were selectively bred, at least nine sired by John Humphrey Noyes, who was 59 years old when the experiment began. A total of 51 applications for parenthood was received and nine turned down by the committee as unfit. Scientifically, the program seems to have been a success. Studies conducted in 1921, when the "stirps" ranged from 42 to 52 years of age, indicated a death rate far below the norm for those days, and the talents and intellectual achievements of many of these products of scientific human breeding have been amply demonstrated. From a human relations standpoint, it was less successful, arousing barely concealed resentment among those judged unfit, among some young women who came to see themselves as guinea pigs, and among some younger men who felt their elders claimed a disproportionate prerogative.

The advent of stirpiculture was openly proclaimed by Noyes, to the vast fascination, prurient and otherwise, of the outside world. H. G. Wells came to Oneida to inspect the results; Havelock Ellis declared Noyes "one of the noblest pioneers America has produced." Pierrepont Noyes, son of John Humphrey, father of the present chairman of Oneida Ltd., organizing genius of the modern industry, U.S. member of the Rhineland Commission after World War I, recalled a discussion of the subject with George Bernard Shaw at a London dinner party Wells gave in honor of the Noyeses. While Mrs. Shaw fumbled for the inevitable question, GBS asked it directly. Noyes' proud response, "Yes, I was one of the stirpicultural children" - as was his wife - broke the ice, and "the silence which had followed Shaw's question was dispelled by a deluge of questions from the other guests."

The long run of complex marriage and later stirpiculture aroused a fever of curiosity among the general population as well as the literati. When a railroad was built through the 700 acres of community farms in 1870, visitors by the thousands came to inspect, to pry, to ask rude questions, and to roam the new Mansion House, a massive brick building forming almost a full quadrangle. They were warmly received, encouraged to picnic on the broad lawns, and entertained with concerts in the frescoed Community Hall, with its commodious stage and three-sided balcony. A generation accustomed to bustles, trains, and elaborate coiffures was shocked at the short hair, short dresses and pantaloons of the community women and at their faces tanned by outdoor living - "a discoloration which they take no pains to conceal with powder." But the objective observer found no evidence of the orgiastic atmosphere he might have expected. "I am bound to say as an honest reporter," Thomas Wentworth Higginson wrote in the Woman's Journal, "that I looked in vain for the visible signs of either the suffering or the sin. The Community makes an impression utterly unlike that left by the pallid joylessness of the Shakers, or the stupid sensualism which impressed me in the few Mormon households I have seen."

The attitude of the local clergy, however, was hardly so benign. The community had successfully withstood threats against their continuance, reminiscent of the uproar which drove them from Putney, as far back as 1850 - largely through testimony from their neighbors that "We regard them as honorable men, as good neighbors, and quiet, peaceable citizens ... ; and we have no sympathy with the recent attempts to disturb their peace." But in the 1870s, a group of Methodist and Presbyterian clerics and laymen, led by a professor of Moral Philosophy at nearby Hamilton College, was determined that the Oneida Community must be stamped out. "The hideous thing that hides away from the light of day, and in dens and midnight hells revels in debauchery and shame," one charge read in defiance of the community's open publication of its principles and its standing invitation to the public to visit at will. The forces of righteousness were ridiculed in the liberal press for their hypocrisy, Puck editorializing "We have all over this land a vast tribe of gentlemen in white chokers who, entertaining the same idea, prefer to carry it out in secret and unavowedly." The Oneida County District Attorney contended: "It is easy enough to reason out that their social habits are wrong because they don't conform with ours - that is, with what we say ours are - but if indictments could be procured on the ground of general immorality, who wouldn't be liable?"

But the days of the Oneida Community were numbered, not so much as a result of attacks from "The World," but from dissension within. Factions were forming, the absolute authority of the aging John Humphrey Noyes over personal and community affairs was no longer undisputed, a new generation was growing up in an age as fired with skepticism as their elders' was with religious radicalism. And - ironically - many of the young people of Oneida were fomenting a sexual revolution, rejecting the accepted sexual morality of their parents with a shocking yearning for monogamous relationships.

As Noyes' granddaughter, novelist Constance Noyes Robertson, writes:

In so common a happening as a divorce, the breakup of a single marriage, the odds must be a hundred to one against a single simple cause for the parting. In the case of the dissolution of the Oneida Community, inhere there was not a single but a complex marriage, where there was not the usual small family unit but a family unit of nearly three hundred persons, the odds against a single simple cause of its breakup must be astronomical. And add to the incredibly complicated web of human relations existing there the almost equally complicated structure of its business organizations and you have a riddle to daunt a modern Oedipus.

Whatever the threads in the skein of disorganization, the threat of legal action was in the air, and John Humphrey Noyes became convinced that his removal from the jurisdiction of New York State authorities was the price required for the salvage of the community. So, on a night in June 1879, the prophet took leave of his flock, as secretly as he had at Putney, this time to live out the remaining seven years of his life in a cottage at Niagara Falls, Ontario, the site of Oneida Ltd.'s present-day Canadian silverware factory. As an early biographer wrote, "... the angels must have wept at the differing destinies of these two grandsons of old Rutherford Hayes - mediocrity in the White House, genius on its way to exile."

The faithful Harriet, his disciple and wife of almost 50 years, joined Noyes shortly in Niagara, along with a few old associates. Many of his children came to visit. He continued to exert a strong influence on community affairs, even at a distance, and counseled the wisdom of abandoning complex marriage later in the year, in part to placate the clergy, in part to put the men and women of the community in conformity with the laws of "The World." Sorting out the intricate relationships of women who had borne children to more than one man and men who had fathered offspring of several women into conventional marriages made for strange households and, inevitably, for a share of human misery.

The final dissolution came in 1880, when the Oneida Community was converted into a stock company, shares going to individuals on the basis of the longevity of their membership and the amount of their original contribution, and provision made for the education of the young and the care of the old. At the time, the company was capitalized at about $600,000; for years it paid its stockholders an annual dividend of six per cent.

The Mansion House still stands, the property of Oneida Ltd., within sight of the company's administration building and near the vast silver factory. Almost a century after the breakup, its 475 rooms - a few converted into modern apartments - still house many direct descendants of John Humphrey Noyes and his disciples and one nonegenarian who was born into the old community. Portraits of the man some called "saint" and some "madman" and his followers hang in the hall adjoining the elegantly furnished upstairs sitting room; parties, weddings, and entertainments are still held in Community Hall; most residents still eat in the common dining room, now staffed by outside help; trees grown tall shade the peaceful quadrangle. An air of gentleness and serenity pervades, recalling the response of a long-ago woman member of the community to a question about the source of "the sweet, clean smell" of Oneida: "It is the odor of crushed selfishness."

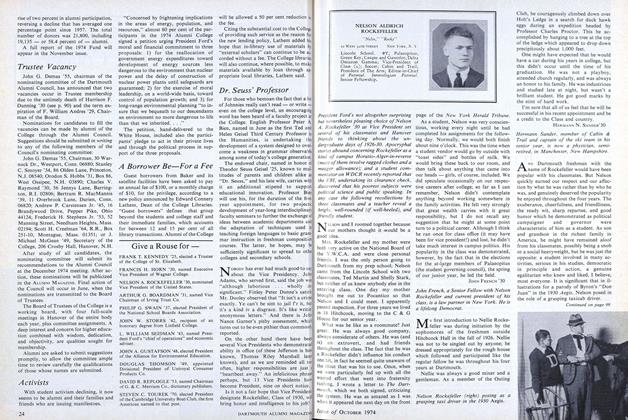

Members of the Oneida Community gathered in the quadrangle of the "new" MansionHouse, the women's dress unconventional for the times, but the fancies of the young couplein the foreground apparently turning in ways traditional to spring. Below, communityyoungsters on an outing under the care of "parents" assigned to the Children's House.

Members of the Oneida Community gathered in the quadrangle of the "new" MansionHouse, the women's dress unconventional for the times, but the fancies of the young couplein the foreground apparently turning in ways traditional to spring. Below, communityyoungsters on an outing under the care of "parents" assigned to the Children's House.

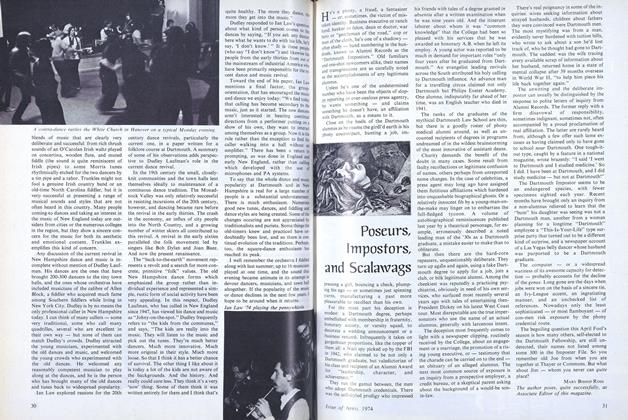

A contemporary engraving of the new Mansion House, constructed in the early 1860s.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMore than a beast, Less than an angel

October 1974 By PETER A. BIEN -

Feature

FeatureMountain of Storms

October 1974 By ANDREW HARVARD, TODD THOMPSON -

Feature

FeatureBelieve It or Not!

October 1974 By GREGORY C. SCHWARZ -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

October 1974 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

October 1974 By WALTER C. DODGE, DR. THEODORE MINER -

Article

ArticleDr. Seuss' Professor

October 1974

MARy BISHOP ROSS

-

Feature

FeaturePoseurs, Impostors, and Scalawags

April 1974 By MARY BISHOP ROSS -

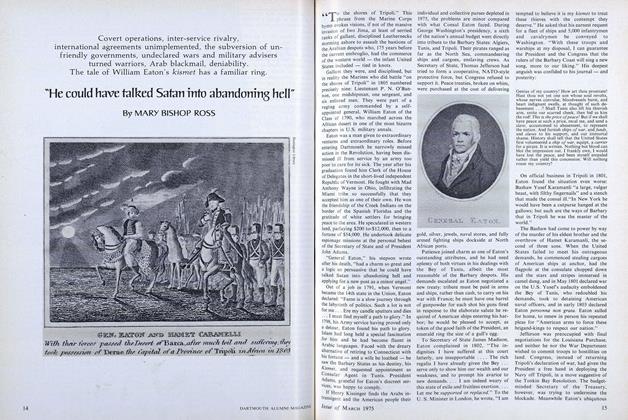

Feature

Feature"He could Have talked Satan into abandoning hell"

March 1975 By MARY BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

FeatureOBESITY

November 1975 By MARy BISHOP ROSS -

Article

ArticleRichard Owen Sits on Two Benches: Judicial and Piano

MARCH 1983 By Mary Bishop Ross

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryBROKEN CLAY PIPES

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureIT'S GOOD

APRIL 1989 By Dinesh D'Souza '83 -

Feature

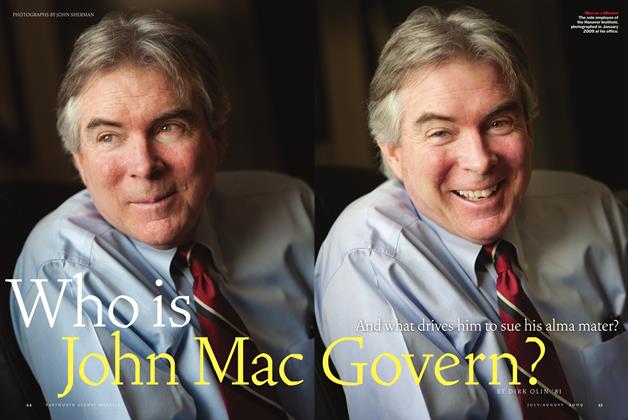

FeatureWho is John MacGovern?

July/Aug 2009 By Dirk Olin ’81 -

Feature

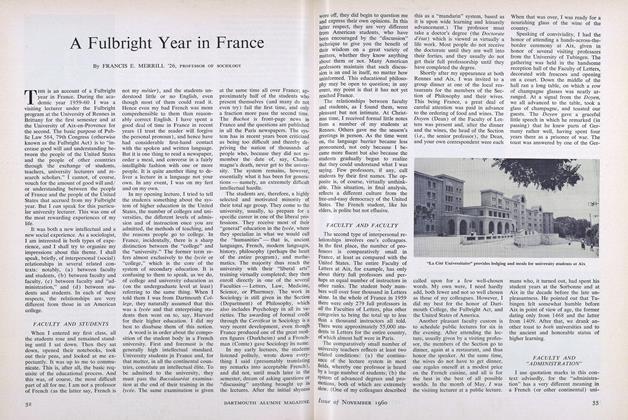

FeatureA Fulbright Year in France

November 1960 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Feature

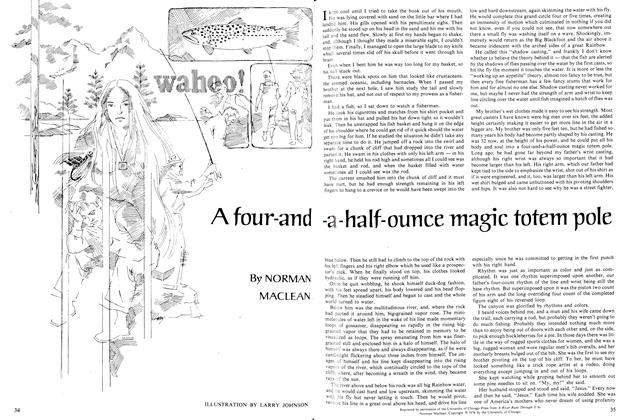

FeatureA four-and -a-half-ounce magic totem pole

June 1976 By NORMAN MACLEAN -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWell-Earned Minus

MARCH 1995 By William C. Sadd '62