WAYNE G. BROEHL

More than five years ago, Wayne Broehl began a long-term study of the attitudes and practices of rural businessmen in southeastern India. The project, seemingly an odd one for a business school professor from Hanover, New Hampshire, was aimed at improving the distribution of that most mundane of commodities, fertilizer. Now, like a fledgling seabird caught in a slick, Broehl's plan has fallen victim to the rocketing price of oil, providing a brutal lesson of the uncertainties of the marketplace and dashing hopes, at least for the present, of giving impetus to the Green Revolution in India.

From his earlier studies of the potential role of the entrepreneur in several Latin American countries, Broehl became convinced that the entrepreneurial spirit could be a key to bootstrap efforts to improve the living standards of millions of people perched on the rim of starvation. Although his focus was India, he reasoned that if the creative impulse of the individual small businessman could be triggered there, it could provide a pattern for economic development anywhere.

Broehl wanted to establish whether the one- and two-man business characteristic of India could become "agents of change," inducing farmers to attempt new ways of intensive production and encouraging a break from the combined grip of poverty, inertia, and tradition without rending the fabric of Indian society. With support from the Ford Foundation and the government of India, he traveled to the subcontinent five times between 1968 and 1973, gathering mountains of data with the help of colleagues from four Indian graduate schools of management.

Later, the information was fed through the Dartmouth computer to frame several working theories. Broehl identified personality traits which would have to be activated if individuals were to make the extra effort to bring about change in an agrarian culture resistant to change. And he identified fertilizer distributors, of which there are some 70,000 scattered throughout India, as the most promising self-starting missionaries of modern farming techniques. More than other small businessmen, such as millers, shopkeepers and bankers, the fertilizer distributors already had some notion of how the Green Revolution had benefited the farmer working with new "miracle" seeds, benefited themselves as businessmen, and benefited India.

To find out whether these merchants could make a difference, Broehl and his colleagues selected 20 distributors from the state of Tamil Nadu and put them through a week-long learning and motivational experience. Whether they knew it or not, the 20 men engaged in that fine business school technique of "gameplaying" to learn the concept of service and how to move their farmer customers to improve efficiency through new equipment and methods.

The first results of that first training session, which Broehl called an "innovation seminar," were encouraging. The Indian teachers and civil servants working with him reasoned that even if only ten per cent of the 70,000 fertilizer distributors could be inculcated with what they termed a "change mentality," it would help make a marked increase in the country's agricultural output.

Then came the Arab oil embargo and a quantum jump in world petroleum prices. As a result, in India as elsewhere, the price of oil-based products like fertilizer skyrocketed, leading to severe shortages and black markets. In addition to a withering blow to the Green Revolution, this unforeseen development has caused in Broehl's view an incalculable indirect loss, effectively short-circuiting the program for developing "agents of change" at the very moment his program was to be tested on a large scale. Even for those fertilizer distributors who went away from their training seminars with a new vision, the return to shortages, high prices and black market temptations have encouraged a drift backward to old patterns, to the way it has always been done. Broehl hasn't given up (a book on the fruits of the five-year study Village Entrepreneur, is ready for the publisher), but he is keenly aware that decisions made by oil producers far from the Indian peasant villages where he worked have sapped a lot of the momentum from a promising venture.

A historian as well as an expert on comparative business systems, Broehl did receive a surprise personal bonus from his Indian study. Becoming interested in the philately of 19th century colonial India, he acquired a packet of 32 envelopes just for the stamps. Inside was the bonus, a series of letters from a lieutenant in the East India Company militia stationed in northern India. To his mother in England, the young subaltern described his part in quelling the Sepoy Mutiny against the British raj in 1857-58. The letters proved so fascinating an insight into that critical era of Indian history that they have since become the core of another book Broehl is writing. A similar find of previously undisclosed material in the files of the Reading Railroad developed into TheMolly Maguires,, Broehl's book on the secret society of Irish miners that terrorized the Pennsylvania coal fields in the 1860s and 1870s.

Broehl, who has written six other books, joined the Tuck School faculty in 1954, after teaching at Bradley and Indiana universities and working in the labor relations department of Western Electric Company in Chicago. A graduate of the University of Illinois in 1946, he received an M.B.A. from the University of Chicago in 1950 and a doctorate from Indiana in 1954.

In addition to his writing and research, Broehl has moved in new directions as a teacher. His course on business environment, which he began nearly 20 years ago, was one of the first designed to make future professionals aware of the social responsibilities of business. And in keeping with the mandate of Benjamin Ames Kimball, 1854 - railroad entrepreneur, banker, and Dartmouth Trustee for whom the Kimball professorship was named - Broehl has established two teaching bridges between Tuck School and the College. In collaboration with the Geography Department, he has helped to develop a course on world food problems; taken jointly by graduate students and undergraduates, it may be the first of its kind at Dartmouth. He also is a member of an interdisciplinary faculty involved in the College's Asian Studies Program, and, in yet another field of arcane skills, the Trustee's Advisory Committee on Investment Objectives.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"He could Have talked Satan into abandoning hell"

March 1975 By MARY BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

Feature"How Ya Gonna Keep 'Em Down on the Farm?"

March 1975 By ROBERT L. HIER -

Feature

FeatureAnother Day, Another Dollar

March 1975 By V.F.Z. -

Feature

FeatureA Renaissance of Slashers and Bashers

March 1975 By SID LEAVITT '62 -

Article

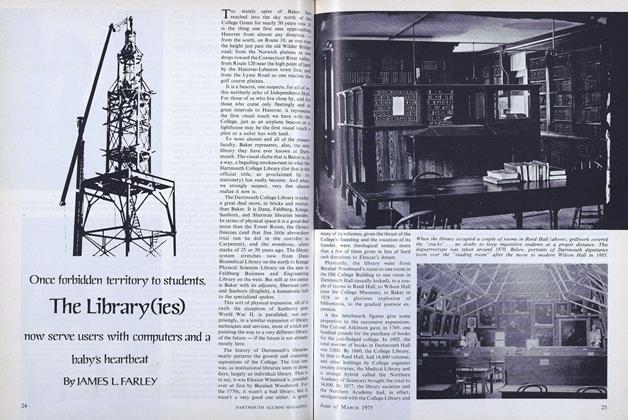

ArticleOnce forbidden territory to students, The Library(ies)

March 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

March 1975 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE

R.B.G.

-

Article

ArticleEndowed Professorships

FEBRUARY 1973 By FRED BERTHOLD JR. '45, R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleIt's Still "Men of Dartmouth"

NOVEMBER 1972 By R.B.G. -

Feature

FeaturePoet of Place

December 1973 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleJAMES M. COX

April 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleJAMES BRIAN QUINN

December 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleTHOMAS A. SPENCER

February 1975 By R.B.G.