Governance: Rights and Unrights

We learn that from earliest recorded history people have been struggling with concepts and forms of government. We still are, and that's what this piece is about. Eleazar Wheelock may have been a very pious man, but he was also a theocrat. His word was law because as a clergyman he was believed to be inter- preting the will of God. The theocratic style which he exemplified persisted into the 20th century in a number of colleges and univer- sities. Nicholas Murray Butler of Columbia, Charles Eliot of Harvard, and my first boss, Palmer C. Ricketts of Rensselaer, are three fairly recent examples.

At a faculty meeting which I attended in 1932, the Rensselaer faculty voted to relieve the president of the job of coping with minor infractions of college rules by appointing a faculty com- mittee to take over these duties. "Gentlemen," President Ricketts interjected, "I don't think the executive committee of the board of trustees would approve of your action. Just a moment." Whereupon he walked over to a corner of the meeting room in full sight of the faculty and mumbled something to himself. Then Rickefts returned and smiled. "No," he reported, "the executive committee does not approve. Next item of business." Today, if this were to happen at Dartmouth, the people in White River Junction would be disturbed by the howls from the Hanover plain.

There are critics of democracy who call it government by the least able and the least informed, but as Winston Churchill reminded us, with all of its obvious imperfections, democracy is still the most resilient form of governance that human beings have been able to devise. It has been my experience that for colleges a desirable system of governance is almost any system that the college does not presently have. The president is criticized for making decisions without having consulted with the people who are going to be affected by those decisions. When he does not make decisions, he is said to be indecisive, dilatory, and picayune in following the letter of the agreed-upon-law. Apparently, he is supposed to act upon things that the college constituency doesn't care about and to consult with the constituency upon the things it does care about.

The trouble is that the things the constituency cares about are always in a state of flux. When groups get together to hammer out rules for college governance, one of their major assumptions is that succeeding groups will be as interested in participating in governance as they are. The writers of rules for governance are working in an attempt to correct a situation that is causing fric- tion and difficulty. The better they do their job, they believe, the better the governance situation will be in the future. Once "good government" is in place, however, people tend to lose interest. The result is that it becomes difficult to find enough students and faculty members to participate in the over-elaborate governmen- tal system that usually evolves. So, the process falls apart until such time that another hue and cry is set up about "edicts that come from on high."

I have made the following suggestion before, but no one has yet taken it seriously. Instead of meeting to discuss student a faculty rights and responsibilities why not meet to discuss arid draw up a list of actions and decisions in which the students arid faculty have no interest or feeling of competence to This would be a list of student and faculty unrights, drawn up fc,, them. It would give the administration a clear signal to deal with those things promptly and efficiently, saying in effect, "Y01] decide and take care of those. We only want to be consulted about policies that affect our ability to get and give an education and the way in which we interact with each other."

Are there any objective measures of the effectiveness of collegiate governance? As a Yale football coach once remarked "We try to win enough games to keep the alumni ornery but not rebellious." The recent near-rebellion at Boston University is an obvious indication that governance is not working well there This, of course, is a negative indicator, and there should be recognizable warning signals before that kind of indicator appears. Some of these are: Is the college gaining or losing dis- tinguished scholars? In the long run that's what it's all about the quality of the faculty. Of nearly equal importance is the quality of the student body. Does the college have the opportunity to enroll students with the intellectual capacity to get maximum benefit from their College experience? Here the much-maligned test scores of the entering class do have relevance. How is the college judged by its peers? Are faculty members seeking to enter its ranks? Is it being emulated in any. way? Is it referred to as a standard to which other institutions aspire?

Despite these tangible indicators, there are equally or ever more important intangible ones. To paraphrase Thomas Jeffer- son, "That government is best which appears to govern least." What we are all seeking in college governance is one that governs efficiently and with a minimum of obtrusiveness. Before the ad- vent of consumerism and rampant equality, students accepted college governance the way one accepts bad weather. It was there. You didn't much like it, but there wasn't much you could do about it. Now people are constantly trying to change both the weather and the governance when they aren't to their liking.

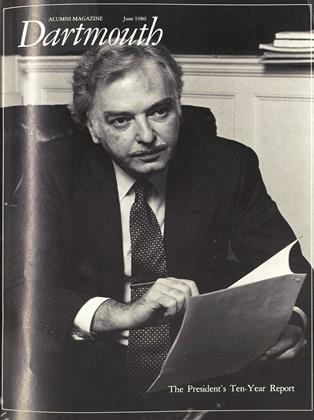

The climate of the campus has a very real effect upon the college's operations, and I believe that climate is created b; something that has received far too little attention. That is the in- fluence of the college's leading scholars and administrators as ex- amples. When President Kemeny was asked to head the Three Mile Island Commission, all of Dartmouth felt complimented. Dartmouth as an institution committed to fairness and truth was symbolized by its president just as it has been similarly sym- bolized by other Dartmouth leaders. In such a climate almost any equitable form of governance has a chance to flourish.

Yet there are some generally accepted caveats about gover- nance. It should not be so cumbersome that prompt decisions are not possible. President Bok of Harvard has recently complained about this, referring to the deadening effect of endless con- sultations. It should not be the principal topic of concern, being - means and not an end. It should not, except on rare occasions, in- volve too many campus people. And it should not ignore the faC; that the legal authority of any college rests with its trustees. Dartmouth's strength is where it should be in the people who compose it. May it continue to find and place in positions o leadership and trust the kinds of people who guided it to its pre sent eminence. That is the ultimate answer to effective g°ur nance.

Richard Schmelzer started his 37 years at R.P.I. teaching Eng oand ended them as general secretary of the institution and sp?classistant to the president.