One of the jobs of curators at the Museum of Modern Art in addition to identifying trends in the recent explosion of artistic creation and refining the historical collection - is "to attempt the very difficult task of evaluating the various new movements . . to calculate which are ephemeral and which are of enduring significance.

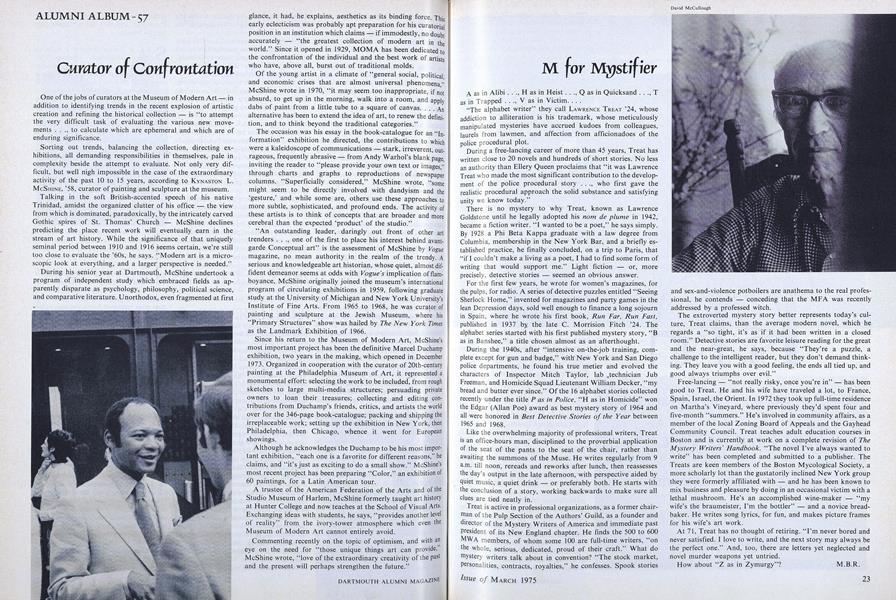

Sorting out trends, balancing the collection, directing exhibitions, all demanding responsibilities in themselves, pale in complexity beside the attempt to evaluate. Not only very difficult, but well nigh impossible in the case of the extraordinary activity of the past 10 to 15 years, according to KYNASTON L. MCSHINE, '58, curator of painting and sculpture at the museum.

Talking in the soft British-accented speech of his native Trinidad, amidst the organized clutter of his office - the view from which is dominated, paradoxically, by the intricately carved Gothic spires of St. Thomas' Church - McShine declines predicting the place recent work will eventually earn in the stream of art history. While the significance of that uniquely seminal period between 1910 and 1916 seems certain, we're still too close to evaluate the '6os, he says. "Modern art is a microscopic look at everything, and a larger perspective is needed."

During his senior year at Dartmouth, McShine undertook a program of independent study which embraced fields as apparently disparate as psychology, philosophy, political science, and comparative literature. Unorthodox, even fragmented at first glance, it had, he explains, aesthetics as its binding force. This early eclecticism was probably apt preparation for his curatorial position in an institution which claims - if immodestly, no doubt accurately - "the greatest collection of modern art in the world." Since it opened in 1929, MOMA has been dedicated to the confrontation of the individual and the best work of.artists who have, above all, burst out of traditional molds.

Of the young artist in a climate of "general social, political and economic crises that are almost universal phenomena" McShine wrote in 1970, "it may seem too inappropriate, if not absurd, to get up in the morning, walk into a room, and apply dabs of paint from a little tube to a square of canvas. ... An alternative has been to extend the idea of art, to renew the definition, and to think beyond the traditional categories."

The occasion was his essay in the book-catalogue for an "Information" exhibition he directed, the contributions to which were a kaleidoscope of communications - stark, irreverent, outrageous, frequently abrasive - from Andy Warhol's blank page, inviting the reader to "please provide your own text or images," through charts and graphs to reproductions of newspaper columns. "Superficially considered," McShine wrote, "some might seem to be directly involved with dandyism and the 'gesture,' and while some are, others use these approaches to more subtle, sophisticated, and profound ends. The activity of these artists is to think of concepts that are broader and more cerebral than the expected 'product' of the studio."

"An outstanding leader, daringly out front of other art trenders . . one of the first to place his interest behind avantgarde Conceptual art" is the assessment of McShine by Vogue magazine, no mean authority in the realm of the trendy. A serious and knowledgeable art historian, whose quiet, almost diffident demeanor seems at odds with Vogue's implication of flamboyance, McShine originally joined the museum's international program of circulating exhibitions in 1959, following graduate study at the University of Michigan and New York University's Institute of Fine Arts. From 1965 to 1968, he was curator of painting and sculpture at the Jewish Museum, where his "Primary Structures" show was hailed by The New York Times as the Landmark Exhibition of 1966.

Since his return to the Museum of Modern Art, McShine's most important project has been the definitive Marcel Duchampexhibition, two years in the making, which opened in December 1973. Organized in cooperation with the curator of 20th-century painting at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, it represented a monumental effort: selecting the work to be included, from rough sketches to large multi-media structures; persuading private owners to loan their treasures; collecting and editing contributions from Duchamp's friends, critics, and artists the world over for the 346-page book-catalogue; packing and shipping the irreplaceable work; setting up the exhibition in New York, then Philadelphia, then Chicago, whence it went for European showings.

Although he acknowledges the Duchamp to be his most important exhibition, "each one is a favorite for different reasons," he claims, and "it's just as exciting to do a small show." McShine's most recent project has been preparing "Color," an exhibition of 60 paintings, for a Latin American tour.

A trustee of the American Federation of the Arts and of the Studio Museum of Harlem, McShine formerly taught art history at Hunter College and now teaches at the School of Visual Arts. Exchanging ideas with students, he says, "provides another level of reality" from the ivory-tower atmosphere which even the Museum of Modern Art cannot entirely avoid.

Commenting recently on the topic of optimism, and with an eye on the need for "those unique things art can provide, McShine wrote, "love of the extraordinary creativity of the past and the present will perhaps strengthen the future."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

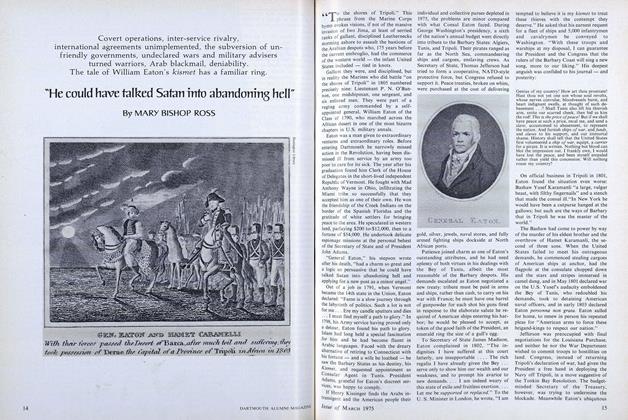

Feature"He could Have talked Satan into abandoning hell"

March 1975 By MARY BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

Feature"How Ya Gonna Keep 'Em Down on the Farm?"

March 1975 By ROBERT L. HIER -

Feature

FeatureAnother Day, Another Dollar

March 1975 By V.F.Z. -

Feature

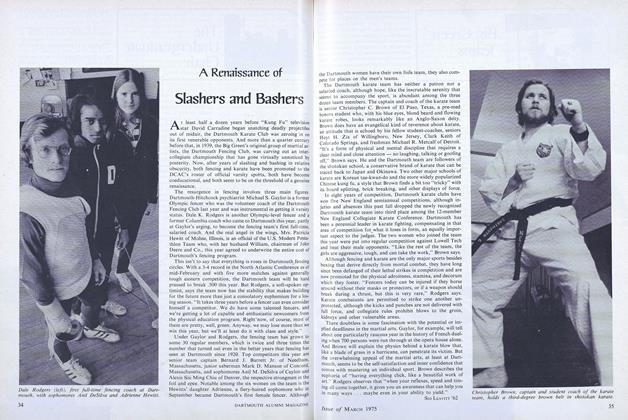

FeatureA Renaissance of Slashers and Bashers

March 1975 By SID LEAVITT '62 -

Article

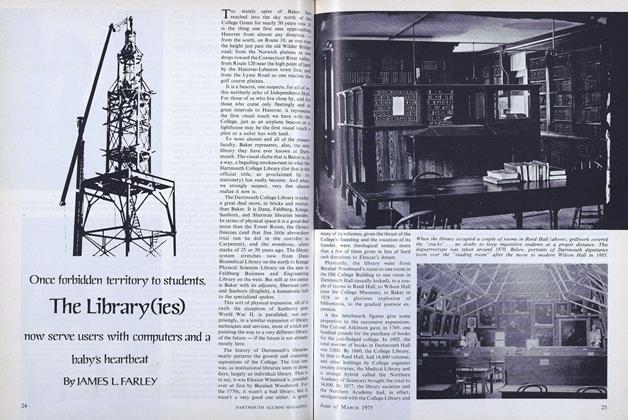

ArticleOnce forbidden territory to students, The Library(ies)

March 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

March 1975 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE