In an article entitled "The University in Steady State," which appeared in Daedalus last fall, I discussed the problem of faculty tenure. I would like to summarize some of my conclusions from that article.

Historically, the reason for tenure was to assure freedom of expression to faculty members. I do not see this as a major argument for tenure at Dartmouth because it is inconceivable to me that anyone would, violate the traditional freedom of the faculty here.

However, there is a much more important freedom that tenure protects. Non-tenured teachers are continually being examined on their performance and cannot afford to engage in research projects of major importance which are unlikely to have short-run results. Nor are they likely to try out radically new ideas in education. Tenure assures senior faculty members a chance to carry out such major research or writing projects and to try new experiments without pressure from chairmen, deans, or the President of the College. I believe that this freedom is essential for the intellectual vitality of the institution.

The question is frequently raised whether tenure allows many teachers to slack off in their efforts. Is it really a device to shield the weaker members of the faculty? From stories I have heard about some other institutions, this may indeed be a fair criticism. However, in my 20 years at Dartmouth I have known only a negligible number of examples where such a charge could fairly be leveled.

The best protection for the future of the institution is a very strict review of faculty members before awarding tenure. I would like to state categorically that there is no industry where executives ever receive as rigorous a review as a Dartmouth candidate for tenure. He or she must serve six years as an assistant professor (with any pre-Ph.D. service not counted). During this time, the faculty member's department will have accumulated an enormous amount of information about performance as a teacher, research potential, and service rendered to the institution. On this basis the senior members of the department make a recommendation on whether to award tenure to the candidate. This recommendation is reviewed by one of the associate deans, and by the dean of the faculty who also accumulates additional information. At Dartmouth it is now standard practice to write to a number of recent graduates who have had courses from the particular faculty member. We ask both majors and non-majors, good students and average students. Our experience is that most young alumni write a long and thoughtful letter that is extremely helpful in reaching a final decision. Outside testimony is sought about the quality of research.

All this information is submitted to the Committee Advisory to the President by the dean of the faculty. This committee consists of six senior faculty members, elected by-the entire faculty, plus the dean. The President chairs the committee, and while not a voting member he does have the right to disagree with it in making a recommendation to the Board of Trustees. Fortunately, over the years this committee has consisted of the best full professors at the institution. I believe that John Dickey turned down a committee recommendation only twice in 25 years, and I have not yet felt the need to do so.

The committee has the dual charge of protecting the rights of individuals and the long-range interests of the institution. It rarely has to exercise the former responsibility, and so the primary concern is whether the institution will be well served with a permanent appointment that is likely to last 30 years. The unselfishness of the committee members is demonstrated by the endless hours of work they put in each year. Having served on the committee for three years as a faculty member and having now chaired it for five years, I am convinced that no institution has a better tenure review system than Dartmouth.

A much more perplexing problem is the question of what fraction of the faculty should be on tenure. If one keeps the figure relatively low, then young faculty members have a discouragingly small chance of attaining tenure, and we would have difficulty in recruiting faculty. If, on the other hand, the tenure ratio is allowed to reach a very high level, it would be costly and would lead to lack of flexibility.

If all teachers who serve the six-year apprenticeship were awarded tenure, about 80 per cent of the faculty would be on tenure. That would be intolerable. It leaves very little room for attracting faculty with new specialities. It would also mean that the typical department of 15 members would have only three young teachers. Given the rapid expansion of human knowledge, this is insufficient to revitalize departmental offerings. Of course, no institution with high standards should ever reach such a percentage. No matter how carefully assistant professors are chosen, some will not live up to our standards and expectations.

What might be an ideal distribution of our 300 faculty members? I would suggest 180 tenure faculty members, 90 assistant professors, and 30 temporary appointments (instructors or visitors). If the tenure faculty were evenly distributed in age groups, then one could make eight tenure appointments each year and always keep the tenure faculty at 180. (In calculating this figure one must take into account not just the fact that tenure normally lasts 30 years, but that we do experience a small attri- tion in the tenure ranks each year due to individuals accepting appointments at other institutions and to untimely death.) Of the 90 assistant professors serving six-year trial periods 15 would come UP tor tenure consideration each year. It would be reasonable to reserve one of the eight tenure positions for an appointment from outside the institution, to fill a particular institutional need. That would allow 7 of the 15 assistant professors to achieve tenure, a level that seems "about right." Thus I have argued for 60 per cent as an ideal tenure ratio for Dartmouth.

Of course, no institution has such a perfect distribution. And as I indicated earlier, in 1970 we had far from an ideal distribution; there were twice as many tenure faculty in the age-group 35 to 50 than in the group 50 to 65. Therefore, between 1970 and 1985 we will experience many fewer retirements than one would normally expect. Since I was acquainted with this problem in the Mathematics Department, I very early started discussions with the Committee Advisory to the President as to how one might solve the dilemma of reassuring the junior faculty and at the same time protecting the long-range interests of the College.

After lengthy deliberation and consultation I announced a new policy for Dartmouth: departments which had a tenure ratio of less than 60 per cent (most departments) would be allowed to rise to that level. And departments that had already exceeded the desirable level would have a token additional position. I looked upon the proposal as a generous one that would cause tenure to rise higher than the optimum figure, but would see us through a 15-year transitional stage. All our calculations indicated that the chance of a typical assistant professor reaching tenure would, under this policy, be as good as it had been in the past decade. I was therefore quite surprised by the violently negative reaction on the part of several departments.

While I still do not fully understand the reaction, I now know some of the causes that contributed to it. One argument was that human beings should not be treated in terms of numbers. This is a very common attitude, and if what is meant is that human beings should not be treated as "mere numbers," I completely agree. But it also has a strongly irrational element in that some decisions cannot be made qualitatively and must be made quantitatively. titatively.How many faculty members should the English Department or the Mathematics Department have? How many of these should have tenure in the long run? How does one assign equitable salaries and still balance the institution's budget? It is impossible to answer such questions without talking about numbers.

A second very important factor was that the job market had completely changed from the 19605. Assistant professors used to know that they had only a 50-50 chance of reaching tenure at Dartmouth, but if they did not make it here there were many other fine institutions that would be happy to offer them a position. Today there is great fear that someone denied tenure will have to leave academic life. This fear is certainly justified, although our experience has been that our junior faculty is of such high caliber that most of those who have been denied tenure have succeeded in finding other attractive positions.

As with any complex issue, misunderstanding contributed to the heat of the debate. Some faculty members seemed to feel that if a given department were allowed to make three tenure appointments in the next decade and they happened to be the number four candidate, they would automatically be rejected no matter how good their record was. Such a procedure would not only be unfair to individuals but would be disastrous for the institution. There was considerable fear that the fate of the individual would depend primarily on the year in which he or she came up for a tenure decision and on how tough the competition was that year. However, experience has proved otherwise. One department, for example, recently had three candidates for tenure and the department itself decided to deny tenure to all three. In another case two members of a department came up simultaneously for tenure and both were granted tenure.

Even those who believed that my plan would continue to provide the same chance for non-tenure faculty members as in the past argued that today we were attracting much stronger junior faculty members. Therefore, some faculty members who a decade ago would have obtained tenure would be denied this opportunity today. And that is absolutely true. While the best assistant professors still reach tenure, there has been an institutional "raising of sights." I know of no way of solving that problem, and for the College it is not a problem but a major benefit.

Given the large number of complaints about my proposed plan, I encouraged the faculty to try to work out a better one. A faculty committee was formed and worked very hard at the task. Making use of the same computer, they concurred with the general objectives I had set, but came up with significantly different means for achieving these objectives.

•>They proposed that instead of limiting individual departments to 60 per cent, irrespective of the present tenure ratio in that department, we should ignore the present status and take measures that in the long run were in the best interests of the institution. They proposed that within the next decade each department mentshould be allowed to make two tenure appointments for each ten members. That is a number calculated to achieve a distribution similar to the idealized one I described above. They further proposed that for those departments that had an unusually small number of members on tenure an additional position be provided. They persuaded the entire Faculty of Arts and Sciences that this was a reasonable plan, and I was very happy to accept it. It has all the advantages of my plan, and the further ad- vantage that it will produce a much more even distribution of faculty by age.

I cite this case as an ideal example of joint decision-making between the administration and the faculty of the College. It was my responsibility to identify the problem and to propose a possible solution. It was certainly the faculty's prerogative to criticize my solution and to work out a better solution of its own. While I reserve the right of judging whether the faculty's solution is better than the one I proposed, the happiest possible outcome is when the faculty's own plan is superior.

Features

-

Feature

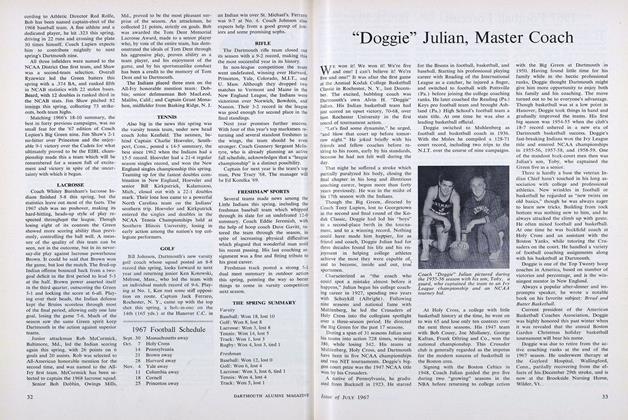

Feature"Doggie" Julian, Master Coach

JULY 1967 -

Feature

FeatureMay 17 Event to Salute Eleazar's Starting Point

MAY 1969 -

Feature

FeatureMy 65 Years as a Class Secretary

JUNE 1959 By CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

FEATURE

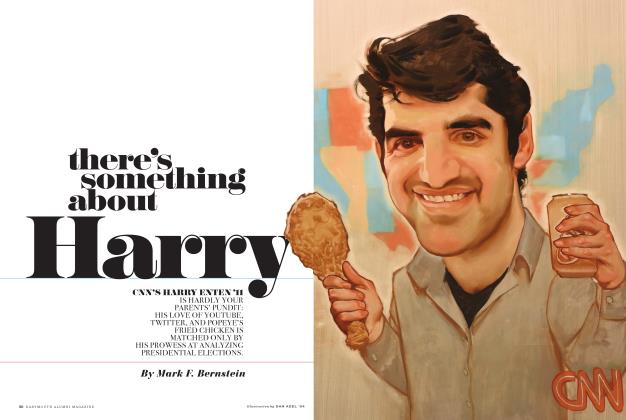

FEATUREThere’s Something About Harry

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2019 By Mark F. Bernstein -

Cover Story

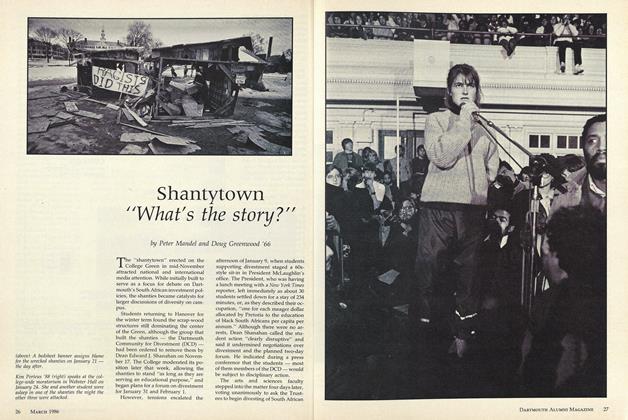

Cover StoryShanty town "What's the story?"

MARCH • 1986 By Peter Mandel and Doug Greenwood '66 -

Cover Story

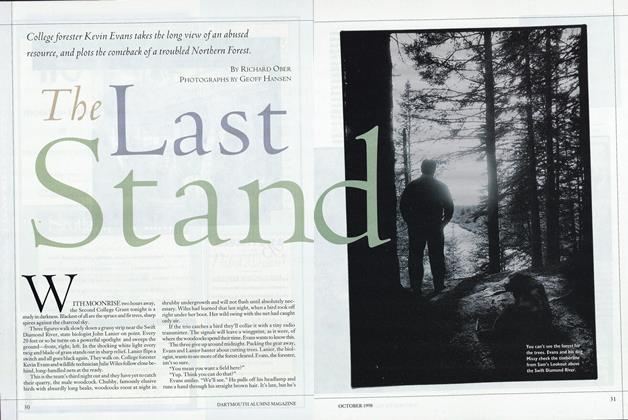

Cover StoryThe Last Stand

OCTOBER 1998 By Richard Ober