Two decades ago Bill Buckley found religion wanting at Yale. What about Dartmouth today?

THE RELIGIOUS college has not altogether disappeared. There are still colleges where chapel attendance is mandatory, or at least strongly encouraged by administrative and peer pressure. There are students and parents who want institutionalized religion to be the foundation of a college education. Few of them choose Dartmouth. Still, there must be parents sending their sons and daughters here who wish the College was a little more "Christian" in its orientation.

I've heard the claim that any college or university not affiliated with the church (some churches more than others), and not sending its quota of candidates to seminary, is sure to be in league with the devil. This attitude seems to apply particularly to the Ivy League. In short, a college's religious concern, or lack of it, is seen by some to be the most decisive influence on a young man's or woman's life, in this world and the world to come. The road to heaven or hell can be traveled in four crucial years.

In God and Man at Yale William F. Buckley Jr. described with singular simplicity the importance of religious instruction at college: "I myself believe that the duel between Christianity and atheism is the most important in the world... I had always been taught, and experience had fortified the teachings, that an active faith in God and a rigid adherence to Christian principles are the most powerful influences toward the good life." It is in this arena of conflict, according to Buckley, that the academic institution's responsibility is most obvious and most neglected: "I propose, simply, to expose what I regard as an extraordinarily irresponsible educational attitude that, under the protective label 'academic freedom,' has produced one of the most extraordinary incongruities of our time: the institution that derives its moral and financial support from Christian individualists and then addresses itself to the task of persuading the sons of these supporters to be atheistic socialists."

If this could be said of Yale in the 19505, how much more might it be true of Dartmouth now? Is Dartmouth really on the front lines of the battle between "atheistic socialists" and God-fearing capitalists? Does there lurk in the ranks of the Class of 1979, as there did, say, in the Class of 1830, a socialist like John Humphrey Noyes, founder of the Oneida Com- munity? Dartmouth's position is not, nor has it been, as definable as Yale's. It defies simple analysis, such as Buckley's. Noyes, for example, does not fit the pattern: he was a Christian socialist. This, however, if may be accounted for by the fact that he pursued his theological studies at Yale.

STUDENTS at the College are continually confronted by enigmatic posters asking, "Is there life after Dartmouth?" or "Is there life at Dartmouth?", which list a panel of survivors to prove that there is. Everyone believes what the survivors say so the approach might be valid. My questions are more enigmatic yet: Is there God at Dartmouth? Where did He come from? And what sort of God is He? I've consulted those who ought to know: College historians, chaplains, religion professors, community ministers, student evangelists, and fraternity members.

A quick survey of the College's history is enough to convince anyone that Dartmouth's God accompanied Eleazar Wheelock to Hanover, sharing the wagonseat, as tradition has it, with a barrel of New England rum. As- every freshman knows, the Reverend Dr. Wheelock, a very pious man, was as serious about God and converting the heathen as some alumni are about resurrecting the Indian symbol. By all accounts, Wheelock was an inspired speaker and, I imagine, a damnably good professor. As recorded in R. N. Hill's TheCollege on the Hill,

Early in his preaching Wheelock was seized by the Great Awakening, a religious virus carrying feverish concern over the fate of the soul to all New England and dividing Caivinists into the damned and the redeemed. Led by Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield, a small band of evangelists converted some twenty-five to fifty thousand people. In the front echelon was Eleazar Wheelock, who in the year 1741 was said to have preached five hundred sermons, "close and pungent and yet winning beyond almost all comparison, so that his audience would be melted even into tears before they were aware of it ... "Wheelock was not considered an extremist. Nonetheless he was a "New Light," was branded as such by the conservative clergy and carried this opprobrium or distinction with him the rest of his life. It was the evangelist in him that led to his Indian School in Connecticut and later to Dartmouth College.

The common assumption is that this "New Light" illuminated the path of the College until the advent of year-round operation, the last Ivy League football championship, and co-education. This was not the case. The light dimmed considerably, Hill suggests, shortly after the establishment of the College: "Religion was so far in decline that only one member of the Class of 1779 was known publicly to have been a professing Christian." Even taking into account inevitable closet-Christians, it seems obvious that God, after His first few years, was having a hard time getting tenure. Perhaps His demands were too radical, like Jonathan Mirsky's, or perhaps He failed to publish. In any event the "Dartmouth Spirit" had a pronounced secular orientation. Students weren't interested. What they were interested in, say the historians, were spirits and spirited pranks.

The history of the Holy Spirit, for the next 100 years, had its ups and downs. The spirit of controversy reigned for a time in the dispute over the College's relationship with Congregationalism, the town of Hanover, and the state of New Hampshire, culminating in the Dartmouth College Case. The spirit of drunkenness and licentiousness, usually residing, it is said, in White River Junction, also had its heyday on campus.

The 1870s, however, saw a return to the spiritual ideals of the founder: "An inducement to rectitude," according to Hill's account, "was an old-fashioned revival of the early 1870s, during which many class leaders were converted. The vision of troublemakers who could not see the light was improved by warrants to spend from three to six weeks in some clergyman's family."

Matters went so far that by 1875, Clifford Smith, a freshman, could write home to his mother about the pleasures of attending not one but six church services on a Sunday. "If the number of meetings one attends Sunday is an index of his goodness," Smith burbled, "I ought to be a pretty religious young man, for I went to six meetings yesterday. First our usual forenoon meeting at half past ten, and we had an excellent meeting, then our class prayer meeting which was fuller and more interesting than we have had before, there being about 35 present. That was out at half past twelve, then I ate dinner and at 12:45 started with two others for Norwich. As their service begins at one, we were a little late, but had a good sermon. Then at four went to the Sabbath school, then chapel at five, and finally, to the evening service at seven o'clock."

By this definition the majority of today's Dartmouth students are neither religious nor good. The Reverend Warner Traynham '57, dean of the Tucker Foundation, describes the Sunday evening Rollins Chapel service as "halting along." Citing last year's average attendance as 40, he counted last Sunday's congregation to be 14. Traynham quotes one of his predecessors as saying he first realized the true meaning of the College motto, AVoice Crying in the Wilderness, when he stood to preach in an all but empty chapel.

Despite the subdued enthusiasm for college chapel, Traynham maintains there is still a place for the effort. The chapel service is billed as addressing issues peculiar to Dartmouth, a point of reference not shared by the community churches whose concerns are primarily oriented to life outside of Dartmouth.

Why don't students attend? Dean Traynham declares that the chapel service, which convenes in the evening, does not "compete" with local churches, whose main worship services are in the morning. Most of the students who would go to church anyway, he speculates, probably do so out of habit Sunday mornings. Sunday evenings, for most, are a time to study.

It may also be the case that most students who would go to church anyway want a run-of-the-mill, comfortable worship, which the chapel service, in a strict sense, is not. What is wanted may be a sit-in-the-pew-and-listen religion that looks like the religion dispensed by the church back home. The specific social orientation of the chapel service is something to which most would rather not commit an hour of a Sunday evening, studies or not. Many of the students seem not much interested in "church" in any form, perhaps as a matter of principle or as an expression of freedom while they're away from home. In short, there is a limited consumer public for the Sunday product, no matter how it is packaged. The consumer public that does exist wants a familiar gospel and familiar ritual.

The number of students who do attend community churches, or who attend a more "spiritual" student-sponsored fellowship meeting immediately following the chapel service, is significant. Most of the Hanover churches have special student ministries in addition to their ministry to the permanent local community.

The Reverend John Lemkul, pastor of Our Savior Lutheran Church, has 150 students on his mailing list and sees 40 or 50 of them in church on Sunday. Several students usually participate in the liturgy of the worship service itself. The Lutheran Church also maintains a student center, in which three students are residents, and which is open at all times for general use. It serves as a recreational and fellowship facility.

The Church of Christ, the "White Church," sustains a similar interest. Twenty or so students are members, 150-200 students come to services throughout the term, and about 15 participate in a weekly Bible study. Mary Kath Cunningham is employed as a special minister to students.

The wine-and-cheese set, frequenting the Episcopalian Edgerton House, receives the full-time services of the Reverend David Mcllhiney. Some 30 students regularly visit the house during the week and participate in a ten o'clock communion service held Sunday nights. According to Mcllhiney, discussion and conversation afterward sometimes continue until two a.m. Monday.

Without exception, the community clergy cite an increase in the extent of student association with their churches over the past few years. McIlhiney sees a "great increase since the fall of 1974." He attributes the increase to changing student attitudes, much less rejection of established institutions, and much more acceptance of the Christian tradition. This trend is reflected in the fact that most of the students who do visit Edgerton House are freshmen or sophomores. (It is worth noting that there are two distinct groups of students informally affiliated with the Episcopal church. The 30 who frequent the student center rarely attend Sunday morning services. The 20 students usually in church on Sunday morning, most of them members of the Dartmouth Christian Fellowship, rarely visit the house.)

Mary Cunningham has noticed "more and more interest" among students attending the Church of Christ. She also sees less anti-institutional bias among students than in years past. These students, most of whom "have roots in the church already," are predominantly underclassmen. "I think they're going to stay with us," she says. John Lemkul attributes the increase in students at the Lutheran Church to the same sort of "change in student attitudes."

An important religious affiliation on campus, already mentioned, is the Dartmouth Christian Fellowship, a welldefined but informally organized group of conservative, "fundamentalist" Christians. Three years ago Don Drakeman '74 wrote a term paper, "A Sociological Introduction to the Dartmouth Christian Fellowship," for a religion class he was taking at the time. While the paper is dated, I believe it still gives a more or less accurate description of the attitudes and activities of the fellowship today.

In Drakeman's opinion, "there are two key words which describe most meetings and activities of the fellowship - enthusiasm and spontaneity. The enthusiasm is evident throughout, especially in the singing and the outbursts of exclamations like 'Praise God!' The spontaneity is evidenced by the fact that very little is planned in advance.... The attitude of the fellowship seems to be that to plan things to a greater degree would obstruct 'the leadership of the Holy Spirit.' "

The fellowship grew as a response, according to Drakeman, to a sense of spiritual and social deprivation experienced by students. "This is particularly important on college campuses where loose morality tends to flourish and general trends of values are radically different from orthodox Christianity. For those who are interested in following a strict Biblical morality there are very few social outlets on most college campuses...." Drakeman documented this difference in values in a survey of attitudes he conducted. Some sample questions and responses:

"Do you approve of pre-marital sex?" Ten per cent of the responding fellowship members answered "yes" as opposed to 84 per cent of the responding general student body. "Do you approve of the use of marijuana?" Of those responding, only 7.5 per cent of the fellowship replied in the affirmative as opposed to 68 per cent of the student body. Opinion on abortion was also solicited. Twenty per cent of the fellowship responses were in favor as opposed to 87 per cent of the larger student population. A consistent and significant difference in attitude between the fellowship and student body was observed in both social and religious issues. Drakeman discovered that a large number of fellowship members were Catholics.

There is a Catholic student center, Aquinas House, located at the end of Fraternity Row. The center, completed in 1972 at a cost of over $750,000, addresses itself specifically to the religious needs of over 600 Catholic students. Not infrequently, Monsignor William L. Nolan, chaplain for over 20 years, also attends to the spiritual needs of Jewish and Protestant visitors. The funds for Aquinas House, which is independently maintained, were raised around the country from sympathetic alumni and friends of all faiths. Nelson Rockefeller, for example, contributed $10,000.

"Everything points to Sunday Mass at the chapel," says Father Nolan. "Our main concern is to encourage students to go to the sacraments." In addition there is a great deal of religious instruction offered. The chaplain attests to a "frightening ignorance of religion. Most students are about third grade in their religion." Aquinas House offers Bible classes, lectures, weekly discussion groups, and periodic religious retreats. Father Nolan's sermons are primarily geared to instruction. He spends 30 to 35 hours a week in personal counseling.

"The campus ministry at Dartmouth is working better than anywhere else in the country," says the pastor at Aquinas House. There are 20 to 50 students there most of the time, and around 400 Catholics participate in some form of religious activity there. Daily mass, confession, and rosary are well attended.

Father Nolan agrees that student interest in the Church has recently been increasing. He attributes this, in part, to a new world and national situation and to a new dimension of seriousness in students of high caliber. "Students," he says, "are asking some serious questions about life."

Dartmouth Hillel, an organization for Jewish students, serves as a focal point for cultural, religious, and educational life. Formed ten years ago as the Jewish Life Council, it currently involves between 40 and 60 of the 400 or so Jews on campus. Activities include weekly study groups, cultural activities, films, worship, and Friday night dinners at the Hillel House. The house is inhabited by four student residents desiring Kosher cooking facilities and by Rabbi Laurence Edwards, associate College chaplain. Hillel maintains a relationship with the local Jewish community. Edwards also serves as community rabbi.

Outside the main-line Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish traditions there are also a variety of smaller associations or sects which sustain a certain amount of student interest. The Society of Friends (Quakers), for example, advertises the Sunday morning meeting in The Dartmouth and sponsors an open house for students at the beginning of the year.

There are recognized student organizations affiliated with both the Church of Christ, Scientist and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. The Mormons meet for worship on Sundays in South Royalton, Vermont, and gather for discussion on Thursday evenings in a Hanover home. Gordon Holbein '78 states the concerns of Mormons at Dartmouth, a four-member organization, as "first, living and developing a good life directed by God the Father; secondly, serving our Heavenly Father by serving His children in all ways possible, including sharing the goodness of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ."

When asked about the religious con- cerns of Dartmouth students in general, Holbein commented, "... spirituality is suppressed more often than not. I see this in the way a good number of them express a desire to worship once a week, but it generally ends right there.... In other words, I see a great lack of living the things which seem to be meaningful once a week for 30 minutes... religious life is not too big a thing at Dartmouth, to say the least."

Sara Hoagland '76, one of five members of the Christian Science organization, describes the group's "biggest activity" as sponsorship of a member of the National Board of Lectureship for a campus program. They also "hold weekly meetings . . . where one member reads from the Bible and from Science and Health with Keyto the Scriptures by Mary Baker Eddy. The meeting is then open for about 30 minutes of remarks and testimonies of Christian Science healing, as well as individual observations of how Christian Science has been helpful during the week."

FAITH is not the only path to religious awareness at Dartmouth. Academic study, embodied in the eightmember Department of Religion, is also an avenue. In his book Buckley singled out the Religion Department at Yale for particular condemnation for failing as "a source of pervasive Christian influence" and for its negligible "impact on the vast majority of students." Because of non-Christians purportedly masquerading there as professors of religion, Buckley wrote that "... to the student who seeks intellectual and inspirational support for his faith, it is necessarily a keen disappointment."

My major in religion at Dartmouth has been a great satisfaction. It has been far from comfortable, either spiritually or academically. It has been demanding in both respects - claiming academic excellence and critical thought but not in any sense a "profession of faith."

I asked Professor Fred Berthold '45, an ordained clergyman, one-time dean of the Tucker Foundation and department chairman, about the possibility of conflict between the demands of faith and the demands of reason in teaching religion. Admitting the possibility of such a conflict, he denies any real problem at Dartmouth. "There is a place for a 'religious' college," he says, "if it advertises itself as such. But it is difficult for those places to maintain a first-class academic program. The critical spirit is stifled when there is no opposition." Berthold also points out that Dartmouth's decisive shift to a strictly secular institution was conducted by William Jewett Tucker, the College's last preacher-president, a liberal who was tried for heresy. It was a shift from a small religious college to a national institution, and it was in response to the very real question of the College's survival.

The critical spirit of scholarship in the liberal arts is what the Religion Department, at its best, demands. Its goals are primarily academic: the presentation of information about the world's major religious traditions and training in critical analysis.

There is a distinctive element in teaching religion, Berthold observes. Even though the approach is academic, and the mode of thought is historical and critical, one encounters deeply personal beliefs and values. There is a danger that colleges train people primarily in the skills demanded by contemporary society. The humanities, and religion in particular, offer an awareness of other values and an alternative, or at least a basis of comparison, to one's own.

Over the past 20 years the Religion Department has gradually become more cosmopolitan, adding and expanding opportunities for Judaic and Asian study. "Student attitudes and interests change all the time," Berthold says. "Right after World War II there was a religious boom." The Dartmouth Christian Union was very strong. Then, in the '50s and '60s, personal interest in religion among students declined, although academic interest remained steady. The recent surge in personal interest, he thinks, has been among a minority of students with whom the department, whose interests are broadly religious, rarely comes in contact.

This minority, roughly composed of students whose beliefs could be described as conservative or strictly orthodox, has on occasion informally boycotted certain classes offered by the department. Most notorious for their lack of "spirituality" have been courses in Biblical studies. The objection has been largely to the application of techniques of textual form-criticism to the Bible in place of a more "devotional" approach. Berthold regards this reaction as a reflection of poorly informed, narrowly sectarian, religious instruction in churches and schools.

The Religion Department co-habits Thornton Hall with the Philosophy Department. Whether the marriage was by choice or chance, it has been a fortunate partnership. More than one professor of religion has discovered, half-way through a lecture, the outline of a logical proof for the non-existence of God written on the blackboard behind him.

The 1975 Course Guide, a student publication, said' of the Philosophy Department, "One is so easily seduced into Thornton Hall by the professionals therein exhibiting their extraordinary ability to call into question so many of the beliefs you might have formerly felt justified to hold. One can so easily come to regard what these men possess - their 'philosophical' understanding and their tenacity in argument - as the only things worth acquiring of what Dartmouth has to offer."

Professors of two of the three philosophy courses I've taken began their first lectures with similar questions. One asked, "Does anyone here really believe in God?" The other inquired, "Who thinks they believe in miracles?" It would be unfair, really, to characterize the atmosphere of Thornton Hall, or even of the Philosophy Department, as antagonistic to faith. The antagonism is primarily directed toward slip-shod thinking, unreasonable presuppositions, and assertions not supported by reflection. One can also find in Thornton an affirmation and respect for faith as a category of experience essentially independent of rational inquiry and as a kind of knowledge about the deepest realities of human life. I've heard lectures as inspiring, I'm sure, as any chapel service of 1830. The professionals in Thornton frequently exemplify what scholarship in the humanities should be: a consideration of facts in relation to values, methodology, and conclusion.

The INSTITUTIONALIZATION of values at Dartmouth ostensibly occurs under the auspices of the Tucker Foundation. Its purpose, in the words of The College onthe Hill, is no less than the fulfillment of the highest goals of a liberal arts education:

The William Jewett Tucker Foundation, established by the Dartmouth Trustees in 1951, is designed in purpose and in the person of its dean to witness and further the abiding concern of the corporate college that the growth of conscience should be a part of the Dartmouth experience.

This effort to unite an ancient concern and contemporary circumstance stands on the considered resolve of the Trustees that today's college cannot commit itself in these matters to much more - or to much less - than the conviction that good and evil exist, that it is an educated man's duty to know and choose the good, and that it is part of Dartmouth's work to prepare men to make that choice.

That all sounds good, probably good enough to be part of a commencement speech. It is, in import, part of most of them. I think, though, that for most administrators, faculty, and students, commencement speeches are to the academic year what Sundays are to the work week - too often an affirmation of intentions soon forgotten or ignored. It might not be too much to say that the road to an A.B. degree is paved with such intentions. This is all by way of saying that Dartmouth usually perceives that it is an educated man's primary duty to be successful. I'm all for success. Thank God for successful Trustees who saw fit to institutionalize conscience in the Tucker Foundation. It was a good and noble idea, currently served by five clergymen or chaplains.

The ambiguity of the foundation's charge, "to further the moral and spiritual life of the College," hardly allows for objective evaluation of its success. The College is rich, fortunately, in students whose moral and spiritual lives are in obvious need of furthering. On the other hand, one wonders if the condition of the average Dartmouth student would be any less depraved without the Tucker Foundation than it commonly is at present. Its influence, with respect to its charge, is limited.

The students who do participate in Tucker programs frequently claim for the experience an importance equal to that of their classroom education. What is available, for the student who avails himself of the opportunity, is service and educational experience in environments of extremes. These range from a learning center in Jersey City, to an Indian reservation in Montana, to an Outward Bound course, a prison in Vermont, or an old people's home in Hanover. The hope is that such experience, requiring more than academic proficiency, will be positive in the values it suggests and the demands on character it makes.

The Tucker Foundation also claims to be oriented toward questions of conscience affecting Dartmouth as an institution. The current dean, Warner Traynham, describes his position as a "... chaplaincy that got out of hand. The foundation is concerned with questions of institutional responsibility, is a clearing house for issues of moral concern brought to its attention, and acts as a gadfly in keeping these issues before the College."

An important part of the Tucker Foundation is an organization which was, until recently, known as the Dartmouth Christian Union. The D.C.U., at one time a conservative Christian organization generating wide student support, evolved in recent years into a social service instrument. In recognition of this less explicitly religious orientation, the name was changed to the Dartmouth Community Service. According to Traynham, the College in the '6os drew its social service motivation out of its religious motivation, then gradually lost sight of religion as a basis for action.

Buckley, in his attack on liberalism at Yale, refused to equate the "charitable" work of the Yale University Christian Association with real religious work: "Such a utilitarian conception of Christianity, coupled with this brand of self-effacement and steadfast refusal to proclaim Christianity as the true religion (which is what all genuine Christian leaders proclaim it to be, thus committing themselves logically to the proposition that other religions are untrue), is a sample of the adulteration of religion to the point that it becomes nothing more than the basis for 'my most favorite way of living.' "

When asked about the function and status of religion in a college or university, Traynham cites Dr. Tucker's view of the differences between colleges and universities to illustrate Dartmouth's religious responsibility. In Tucker's opinion, a university's function should be the transmission of culture. The college's function should be broadly religious, meaning the formation of character and the development of values. Knowledge gained should bear on questions of value.

Traynham sees today's Dartmouth as sharing some of the cultural purposes of the university, while retaining its religious purpose as set forth by Tucker. In Traynham's words, "Values don't stand by themselves. They have to be located in a context. Social action presupposes something. These presuppositions should be informed of the experience humanity has accumulated and brought to bear on these questions."

"There is an inescapable connection between faith and action," Traynham says. "You can't believe without wanting to change the world."

Recognizing a current lack of student enthusiasm for world-changing, Traynham describes part of the Tucker Foundation's responsibility as "selling" opportunities for meaningful, important social involve- ment. He considers the present decline in student activism as related to an increase in concern for personal future in the world. Today at Dartmouth, he says, there is "less concern for fundamental questions of value. I want to promote that concern."

Even accepting a broad definition of religious concern, the characterization of student attitudes in the March 1931 issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE is still accurate: "The undergraduate attitude toward religion is at present not so much one of hostility as of indifference."

IN SPITE of this indifference, the Biblical God seems to be taking care of Himself. There is no need or justification for His appropriation by the College, other than its obligation to provide interested students with a chapel and chaplain or appropriate facilities. The opportunities for religious expression actually are varied and numerous. Worship and fellowship take place, for the most part, in conjunction with community churches or their affiliated student organizations. Academic study of religion, appropriately, is critical.

Is there God at Dartmouth? It all depends on what you think He, or She, looks like. Dartmouth is not a "Christian" institution. It is not most of the time even a broadly defined religious institution. Today's concerns are increasingly "cultural" in respect to Dr. Tucker's description of the university function, and increasingly professional in respect to the present demands of the economy. The odds are weighted against the ideals embodied in the Tucker Foundation, however desirable their realization might be. This is not to say that concern for values is absent altogether. Hundreds of students, many professors, several departments, some college offices, and a few administrators devote considerable energy to just that consideration. Preserving a place for God at Dartmouth, if God can be understood to be either an actual or metaphoric embodiment of humanistic values, may be among the College's most formidable challenges.

Vox Clamantis in Deserto: an apt description of attendance at Rollins Chapel services.

Warner Traynham: "You can't believe without wanting to change the world."

Hillel House: involving about ten per cent of the Jews at Dartmouth.

Fred Berthold: "The critical spirit is stifledwhen there is no opposition."

Dan Nelson '75 is one of this year's undergraduateeditors.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhere Men Moil for Oil

March 1976 By KENT JOHNSON -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

March 1976 By McF. -

Feature

FeatureOPTIONS & ALTERNATIVES

March 1976 By D.N. -

Article

ArticlePeople & Places

March 1976 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

March 1976 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON, JACK E. THOMAS JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

March 1976 By WINDSOR C. BATCHELDER, CHESTER W. DeMOND

DAN NELSON

-

Feature

FeatureUncle Sam and Mother Dartmouth

November 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureDrinking

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

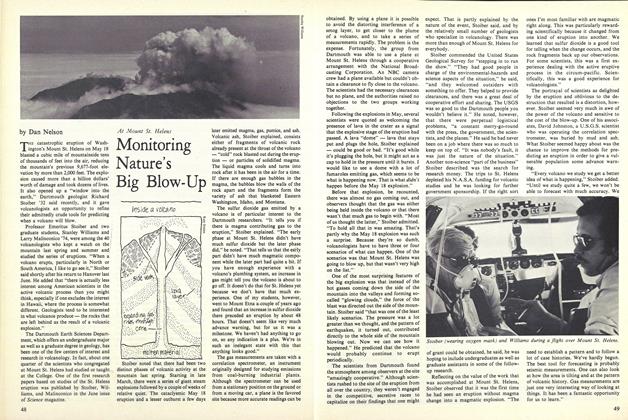

FeatureMonitoring Nature's Big Blow-Up

September 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureConjuring Ethics in the Curriculum at Dartmouth

March 1981 By Dan Nelson

Features

-

Feature

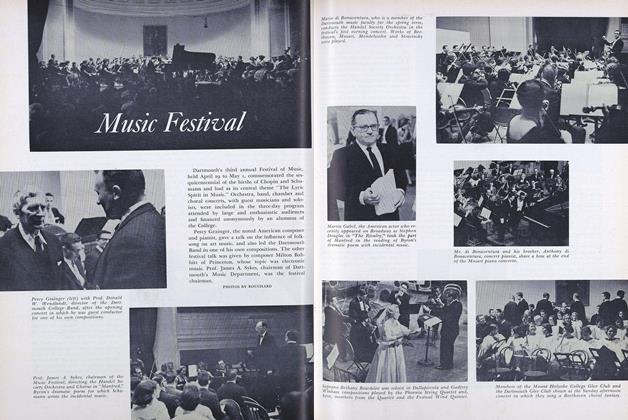

FeatureMusic Festival

June 1960 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

JULY 1963 -

Feature

FeatureThe Peripatetic "Silver Fox"

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Feature

FeatureWhy Dartmouth is Better with Men

MARCH 1997 By Jane Hodges -

Feature

FeatureIs Academia Failing?

MARCH 1988 By Jeffrey Hart '51 and Gregory S. Prince Jr. -

Feature

FeaturePuppets in the Ivy League

JANUARY 1999 By Rich Barlow '81