FOR ALL MEN

We hold these truths to be self-evident. There is nothing hesitant or tentative about the Declaration of Independence. It does not proceed by diffident indirection; it does not ask questions, not even rhetorical ones. It asserts. The Declaration is made up, appropriately enough, of declarative sentences. It is supremely confident. "Self-evident" is a lofty and spacious word

Whence arose this confidence that these are truths, and truths so congruent with all evidence and all experience that they are self-evident? This conviction arose from the fact that every one of these political principles had had a long history and could be traced through the centuries in the writings of authors venerated for their wisdom and insight. These several political ideas rang bells and lit up lights in the minds of 18th-century educated men.

Let us trace the history of one of these truths that Jefferson declared selfevident. Let us take the one that is perhaps the most far-reaching and exciting of them all, namely the reference to "all men." By the use of this single phrase the Declaration in one swoop made itself the concern of all mankind. The impact of the Declaration came from its speaking not simply in terms of the complaints of disaffected Englishmen living in America, but in universal terms, embracing everyone. Indeed, changing just one word in the Declaration of Independence can make it preposterous and bathe it in bathos. George Orwell showed us how it can be done: We hold this truth to be self-evident, that some men are created equal.

What was it in the history of ideas that made the allusion in 1776 to all men seem, to sober persons of excellent judgment, a self-evident truth?

THE UNIVERSALISTIC idea of the commonalty of all men came hard and slowly in the history of mankind. Prehistory, and recorded history, too, is made up of the actions of groups much more aware of their differences than of their similarities. Even the ancient Greeks, whose literature and philosophy have been the matrix in shaping the world outlook of the West, were so Hellenically-inclined that they called everyone who was non-Greek a barbarian and thought of him as being really of a different nature. Nevertheless, it was Aristotle who was one of the first to use the phrase "all men." "All men," he says in the opening sentence of his Metaphysics, "all men by their very nature feel the urge to know." And in one of the fragments ascribed to the poet Anacreon it was written,

No honest man I call a foreigner;One nature have we all.

Alexander the Great transformed Greek culture by extending it to non-Greek peoples. And profound changes occurred in Greek thought as a result of the Greeks' being forced to cope with problems on a world-wide scale. No longer did the narrow parochialism and complacency of a small city-state seem adequate. The world had expanded and the adjustment to it, not by any means painless, required ethical and religious rethinking. This, then, was the age of the emergence of new philosophies, the Sceptic, the Cyrenaic, the Epicurean, and most of all, the Stoic.

What the Stoic philosophy came to can be seen in the Meditations of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius. Or in the life of Cato the Younger. Or in the humanity of Seneca. Or, for that matter, in the young George Washington, who, according to a brilliant essay by Admiral Samuel E. Morison, modeled his life on the tragedy by Joseph Addison entitled Cato. The Stoics developed a conception of God which we now would call deistic. As they looked for the operation of God's laws in the universe, which they hoped to find by the exercise of reason, they were impelled toward a conception of human nature that emphasized commonalty and universalism.

The lawyers of ancient Rome found the Stoic philosophy especially congenial, and to this fact we owe the emergence and the prestige in Roman law of the concept of natural law, ius naturale. The traditional law of Rome was the Law of the Twelve Tables, so exclusive and so jealously guarded that non-Romans were not entitled to use it. As the legions began to conquer non-Roman peoples, either a corpus of new law had to be devised for them or all these numerous tribes and peoples would have to be governed by their own particularistic laws. This was a confusing and cumbersome business, and it is not surprising that the law officer responsible for the administration of justice to these non-Romans, the praetor peregrinus, should look about for some principle of streamlining that would simplify his problem. Thus there slowly grew up a new body of law, called the law of the tribes, ius gentium.

The operative principle of the ius gentium was to try to discover what ideas of right and justice all these various tribes had in common. In consequence it was inherently a body of law that claimed universality. It based itself upon that which all the conquered tribes severally recognized to be either desirable or punishable conduct. The Thracians, for example, regarded rape as a punishable offense, but so did also the Lusitanians and the Mauritanians and every other tribe. The Pannonians, it was discovered, had laws discouraging murder and theft and perjury, just as did the Dacians and the Helvetians and the Britons and the Iberians and the Jews. A common law, common to all the conquered tribes, could be discovered through experience, research, and the use of reason, or, as Cicero called it, right reason. Ius gentium was based upon what was conceived to be universal human attributes.

FOR long the ius gentium was regarded merely as a pragmatic and convenient tool of legal administration, inferior in prestige to the Roman civil law, the Law of the Twelve Tables. But under the influence of the Stoic philosophy, with its fascination for the discovery of laws operating throughout the universe, ius gentium came to seem entitled to more and more moral authority. It was dignified, too, by a' more exalted name, that of ius naturale. Cicero led the way in this movement, and great was his authority, both with his contemporaries and immediate posterity, who admired his republican virtue, and with his more remote posterity Erasmus and indeed the whole Renaissance who venerated him as the great exemplar of humanitas. In his book On the Laws Cicero extolled natural law and declared that the Roman civil law was only a small and narrow corner of the area occupied by ius naturale. "For we must explain the nature of justice, and this must be sought for in the nature of man. ..."

The climax of this slow inversion of values, as a result of which ius naturale came to have the greatest moral authority of all branches of law, is to be seen in the sixth-century codification of Roman law, one of the greatest law codes in the history of mankind, the Code of Justinian. There is a sentence in the Institutes of Justinian that is very striking for our purposes: lure enim naturali ab initioomnes homines liberi nascebantur. - For in the beginning all men by natural law were born free.

The Code of Justinian made its influence felt for centuries. It was the common law of the remains of the Roman Empire; it was, for example, the common law of the southern half of France right up to the French Revolution. The canon lawyers took it over as, from the ninth century onwards, they were fashioning the law of the Church. In the late Middle Ages the Roman law was introduced officially into the Holy Roman Empire; and meanwhile canon law (and so, indirecty, Roman law with its notions of ius naturale) greatly affected the development in England of chancery law or what we now call equity (because all the chancellors of England until Sir Thomas More in the time of Henry VIII were ecclesiastics). It is safe to say that the concept of all men, basic to the notion of natural law, had great influence in the Middle Ages on lawyers, theologians, and philosophers, and continued to express itself in the humanism of the Renaissance.

The concept of natural law is also embedded in Christianity. The Stoic doctrine of ius naturale and of the universality of mankind became an explicit part of the Christian scriptures. Saint Paul was responsible for that. Paul was a Roman citizen as well as a Jew, and thus he was familiar with the philosophical ideas that were the common coin of his time, just as the Greek that he spoke was the common koine of his day. And when he found it necessary to persuade his fellow-Jews that it was right to allow non-Jews to become Christians, he fell back upon the argument from natural law to clinch his contention. One of the most famous texts in the Christian canon (Romans, ii, 14-15) runs as follows: "For when the Gentiles, which have not the law [here Paul means the Torah], do by nature the things contained in the law, these, having not the law, are a law unto themselves; Which shew the work of the law written in their hearts. ..." Written in their hearts. ... In other words, the knowledge of the law is part of the nature of man, an argument from natural law declaring that all men, Jew and Gentile alike, are eligible to be Christians.

Numerous and impressive are the instances wherein the concept of natural law has been put to use in our intellectual heritage. St. Thomas Aquinas made ius naturale the basis upon which his great summa rests; "the judicious Mr. Hooker," as John Locke was fond of referring to him, based his defense of the Anglican Church, in his Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, on an appeal to natural law; Hugo Grotius grounded his great work on international law on the premises of ius naturale; and John Locke himself drew from natural law his own particular extension of that doctrine, namely his emphasis on natural rights.

The reference in the Declaration of Independence to the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God adroitly appealed to two traditions enjoying great prestige. It was certainly appropriate that a reference to the laws of nature be made by a body of which Benjamin Franklin was a member. But the term could also be construed as being the ius naturale of the theologians and the lawyers. Similarly, the mention of Nature's God could signify both the impersonal deity of the deists and the Stoics and the Christian God of St. Paul and St. Thomas Aquinas and John Calvin.

JEFFERSON wrote for colleagues and for a public the elite of whom had been educated in a cultural tradition of which the universalist concepts of natural law and of ius naturale were an important and integral part. Those lawyers and merchants and planters in the Continental Congress, as well as their constituents back home in the 13 colonies, were familiar with this tradition. When they read Cato's Letters, those essays by John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon which had first appeared in the London Journal in the 1720s and which, collected, became "fashionable reading" (according to John Adams) in the colonies in the 1760s and 17705, they were exposed to natural law doctrine, "Men are naturally equal," Trenchard and Gordon had written, and again, "All men are born free. . . . Liberty is the unalienable Right of all Mankind." The colonists may have remembered that back in 1717 John Wise of Ipswich had skillfully used natural law arguments when, in his treatise A Vindication of theGovernment of New England Churches, he defended the principles of democratic organization in the Congregational Churches of Massachusetts. Sir William Blackstone's famous Commentaries on the Laws of England, published in 1765, quickly became a sort of universal textbook for American lawyers. In his introductory pages he comprehensively discussed the principles of natural law.

Moreover, the members of the Continental Congress were men who had been educated in accordance with the great educational innovation of the Christian side of the Renaissance, wherein the literae humaniores, the more humane letters of the Ancients, were blended with Christian piety, the whole aimed at roducing generations of Christian humanists. This was the tradition of Colet and Erasmus and Sir Thomas More. This was the undergraduate education perfected by Cambridge and Oxford in the time of the Tudors and transmitted to Harvard in the time of Charles I, and to William and Mary in the time of William and Mary, and to Yale in the time of George I. Such was the goal of education in the time of George II at King's College in New York City and at the College of New Jersey in Princeton, and at the College of Philadelphia. And it was the aim of the Reverend Eleazar Wheelock's Dartmouth in the time of George III.

Of the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence 23 were university or college graduates, which seems to me a surprisingly high percentage. John Witherspoon and James Wilson had attended the University of Edinburgh, and Thomas Nelson and Thomas Lynch Jr. the University of Cambridge. Francis Hopkinson and William Paca were graduates of the College of Philadelphia, later the University of Pennsylvania. Two members were graduates of the College of New Jersey — Richard Stockton and Benjamin Rush; four were grad- uates of William and Mary — George Wythe, Carter Braxton, Benjamin Harrison, and T. Jefferson; and four — Oliver Wolcott, Philip Livingston, Lyman Hall, and Lewis Morris — of Yale. Seven — William Hooper, William Williams, Robert Treat Paine, Elbridge Gerry, John Adams, Sam Adams, and John Hancock — were graduates of Harvard.

Such a computation assists us in recalling that the men who signed the Declaration of Independence partook of a common cultural tradition that made a universal declaration embracing all men seem clearly acceptable as a selfevident truth. And similarly, all the other components of the political philosophy making up the Declaration of Independence also could be shown, if I had the time, to have had a history and development that made educated and judicious men accept them as truths self-evident. It should be remembered that it was not Jefferson's job after all to draft a document that would strike anybody as new. He wrote later that in the Declaration of Independence he was trying "to place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so firm and plain as to command their consent, ..." And John Adams once huffily remarked that the Declaration of Independence had "not an idea in it but what had been hackneyed in Congress for two years before."

THE self-evident truths- of the Declaration of Independence were enunciated in a context of intense political pressures. What the Declaration said and also what it side-stepped or left unsaid was the result of political exigencies. One was the question of timing. The independence party not only needed a manifesto that could serve as a catalyst in crystallizing public opinion, but they, also wanted a resolution of independence as soon as they could get it. The publication in early 1776 of Tom Paine's Common Sense, with its per- suasive arguments from the Bible showing that it was right to resist kings some people said that all that this proved was that the Devil could quote Scripture was of enormous importance in convincing a Bible-reading populace that it was morally right to declare independence of George III. On June 7 Richard Henry Lee introduced a resolution of independence. This resolution was adopted on July 2. Meanwhile the Congress had appointed on June 11 a committee to draft a declaration of independence and it was this which, after some editing, was adopted by the Congress on July 4.

It is a striking fact that the Declaration of Independence avoided all but the most indirect reference to slavery. There was not even any reference to the slave trade, although in his draft Jefferson had made the perpetuation of the slave trade one of the grievances against George III. "He has waged cruel war against human nature itself," wrote Jefferson, "violating the most sacred rights of life and liberty in the person of a distant people who never offended him, captivating and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the Christian king of Great Britain. Determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought and sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or restrain this execrable commerce; and that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting these very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he deprived them, by murdering the people upon whom he also obtruded them; thus paying off former crimes committed against the liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another." But slavery was already a touchme-not topic politically, and the delegates from Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia threatened not to subscribe to the Declaration should this reference to the slave trade be included. It was expunged.

Another marked characteristic of the Declaration of Independence is that it sedulously avoided any direct reference to the parliament of Great Britain. To judge by the Declaration's complaints, one might suppose that George III had the absolute power of a Louis XIV. In reality, parliamentary supremacy over the crown had been the cardinal fact of political life in Britain for almost a century, ever since the Revolution of 1688. The measures that the colonists complained of most the Stamp Act, the Declaratory Act, the Townshend Acts, and the Quebec Act were acts of parliament. It was most indubitably true that the parliament had every legal and constitutional right to lay the taxes and impositions that irritated the colonists so greatly. Whether it was expedient to do so was, as Edmund Burke pointed out in his famous speeches on America, another matter.

It was disingenuous of the Continental Congress to lay all the colonists' troubles at the door of the king and not at the door of parliament. They must have known better. Benjamin Franklin, who was in London for several years in the 1760s as the official agent for Georgia, New Jersey, and Massachusetts, knew better. It is true that there was apprehension both in America and in the mother country lest George III, through corruption and the votes of placemen, subvert parliamentary supremacy and in effect become absolute. But had he been able to do so, it would have been by seeming to acquiesce in parliamentary supremacy, not in contesting it.

Why did the Declaration of Independence take the line that it did? Partly for the propagandistic reason, no doubt, that it is easier to arouse indignation against a person than against an intangible concept of a complicated con- stitutional situation. But most of all, I think, because at a time when contract theories of government were popular, the Continental Congress wanted to por- tray the king as having broken his contract. All the American colonies save Georgia had received their charters from the Crown before 1688. The colonial charters had not been issued by parliament and it was convenient for the colonists to argue that these charters constituted a contract between king and colony which George III had now broken. It was an ingenious argument but also a disingenuous one. And beyond doubt it has made George III more of a villain in American folklore than he quite deserves to be.

Finally, the exigencies of the situation explain why the Declaration of Independence speaks much more in the name of the rights of man than it does in the name of the rights of Englishmen. The Declaration's vivid and dramatic appeal to the doctrine of natural rights and natural law came quite late in the history of the doctrine of natural law. At just this very time political theory and social theory were beginning to turn for their ideological underpinning toward something else, namely utilitarianism. Helvètius' book, De I'esprit, which so greatly influenced Jeremy Bentham, was published in 1758, and Bentham himself was already inveighing against natural law, as is shown by his Fragmenton Government, published in the very year of the Declaration of Independence.

Nevertheless, the colonists had an excellent tactical reason for insisting in the Declaration of Independence on the rights of man. Repeatedly in their dispute with the mother country they had attempted to prove that their resistance was vindicated by their rights as Englishmen. In a whole series of controversies, in a running battle of pamphlet warfare extending over years, the colonists set forth this contention. But almost without exception they were successfully confuted by pamphleteers on the opposing side. For example, when the colonists complained of taxation without representation, it straightway developed that millions of Englishmen in England, because of limitations of suffrage, were being taxed without representation, too. Thus the Americans were driven in this perennial pamphlet warfare from one outpost to another, from redoubt to redoubt, until at last they took their stand in the highest citadel of all, that not merely of the rights of Englishmen but of the rights of man.

LIKE any great classic, the Declaration of Independence speaks for all ages and all seasons and yet is savorous of the time and the pressures that shaped it. And then, once enunciated, it has in its turn influenced people and events. It, too, has been dynamic. In various ways, some of them subtle and lying far beneath the surface, it has committed us.

What has it committed us to? For one thing it has transmitted the influence ot the Enlightenment to 20th-century Americans to a degree greater than has happened to the citizens of any other country. Our principal political documents, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, and our principal commentary on the Constitution, the Federalist Papers, are intellectual artifacts of the Age of Enlightenment. We still rule ourselves, in part, in the idiom of 18th-century discourse and in the thought patterns of 18th-century ideas. Our Constitution, of all written constitutions, is the oldest one among those still in use. More than any other existing government in the world, the United States can be said to have sprung directly and without hiatus from the Enlightenment. We Americans are endued with the liberalism of the 18th century.

The Declaration of Independence has also committed us, 1 tninK, 10 a somewhat doctrinaire approach to politics. Some of the time we ourselves rebel against this and revel in being pragmatic or, to use a locution that was recently in good odor, "hard-nosed." And then, periodically, there is a revulsion, preventing us from being completely pragmatic for long. In the realm of foreign affairs, the influence of the Declaration of Independence has usually inclined us to be sympathetic to independence movements on the part of other peoples. And on occasion we have been anti-imperialistic. This attitude has not infrequently made our foreign policy seem doctrinaire and rather puzzling and disconcerting to other nations. It can in part be attributed to the Declaration of Independence, I believe, that a great sense of unease develops in the American body politic when our foreign policy and domestic political methods become manifestly at variance with the principles of 1776. Our national experience in the 1960s and 1970s bears out this hypothesis.

And who can overestimate the magnitude of the importance in our history of having the Declaration of Independence proclaim that one of our unalienable rights is the pursuit of happiness? Jefferson might have followed John Locke - comparison of texts shows that he often used the exact verbiage of Locke's Second Treatise on Civil Government and had-he done so here he would have repeated Locke's dictum that man's natural rights are to "life, liberty, and property." Instead, Jefferson substituted "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." It is fortunate that he did so. Our history and politics would have been even more conservative than they are had our most sacred political document enshrined property rights as equal in sanctity to the rights of life and liberty. Happiness is a philosophical concept, and Jefferson has invited us, almost forced us, to contemplate it and, by doing so, to enlarge our conception of the function of government. This, too, is part of the liberalism of the Enlightenment. Happiness, everyone knows, is pursued in an infinity of ways. Who can say but what the insertion of that phrase in the Declaration of Independence has contributed to making us a nation more tolerant and more pluralistic?

AND now it comes to the point of asking whether today there is any dynamism left in the Declaration of Independence. Or is it moribund? Here we are at the Bicentennial. Are we celebrating a renewal or a wake?

Life in the United States has been more nearly consistent with the principles of the Declaration of Independence in the 20th century than it was in the 19th. Sometimes, though, that has not seemed to be saying a great deal. But when you think of the situation 150 or 125 years ago, you find that almost half the country had set its face against the proposition that all men are created equal. It was only the Abolitionists who wholeheartedly supported the idea. And the rest of the country, in a desperate effort to hold the Union together, played down or put down the Declaration of Independence. It was a Dartmouth alumnus, RufUs Choate, an orator of national reputation, who in 1856 enunciated the great put-down of the 19th century. His phrase became very popular, and it still is repeated from time to time. He spoke of what he called "the glittering and sounding generalities of the Declaration of Independence."

And yet there grew up in the 19th century that hope for our country, that sort of nostalgia for the future, that we call the American Dream. Nor has it yet, in an era of hard noses, lost its poignancy and charm. And what is the American Dream? Is it not a yearning for the time, always beckoning and always deferred, when the self-evident truths of the Declaration of Independence will be achieved?

Does our century continue to have a concern for "all men"? Of course it does. We see it in the way in which we are learning that the phrase "all men" includes all women, too. We see it in our increasing recognition of women's rights. We see it in the International Women's Year conference at Mexico City in 1975. We see it in our awareness of the needs and aspirations of underdeveloped nations, of the politics and pressures of the Third World, in our concern, so characteristic of the hopes and horrors of this century, with the concept of genocide. And we see it in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in the recent restatement of those rights in the Helsinki Declaration of August 1, 1975.

The methodology of the Declaration of Independence was to discover what was believed to be reliable generalizations regarding the nature of man and to deduce from these generalizations political principles appropriate to creatures with such a nature. Well, of course we are still doing that, still making discoveries regarding the nature of man. That is what our archaeologists and our biologists, especially our geneticists, are doing; and our social scientists, most especially the social psychologists and the anthropologists. "All men," reads a caption on the wall of the Anthropological Museum at Mexico City, "todos loshombres solve identical needs by different methods and in distinctive ways." What is the correct answer to the question of the nature of man? A theoretical question? Nothing can be more practical. Ask any racist. Ask the Nazi Alfred Rosenberg and Joseph Goebbels and Adolph Hitler.

IF you are scornful of the Declaration of Independence because in American life there is such a gap between the ideal and the real, if you think its promises hollow and its rhetoric false, then remember Barbara Jordan of Houston and her appearance on television when the Rodino committee was considering the impeachment of President Nixon. For almost a hundred years the United States Constitution was not the Constitution of the blacks, she said, but it has become "my Constitution now." Similarly, if the Declaration of Independence is not yet your Declaration of Independence, make it so. And if the struggle seems discouragingly long and progress slow, remember that five years of hardship lay between Philadelphia and Yorktown. As Thoreau wrote in Walden, "If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them."

How encouraging it is that ours is an era of great activity and achievement in the assertion and in the political and juridical definition of rights. The clamor of black groups, women's groups, ethnic groups, gay groups, consumer groups is making our century resound. Seldom if ever in our history has there been greater action in the courts, in minority groups, among public-interest lawyers, all in the effort, to use the language of the Declaration of Independence, "to secure these rights." The instrument these groups "are using is the Constitution and its Amendments, but these are, in logic as well as time, the sequel to the Declaration of Independence. And this ferment of our times is manifestly dynamic, a reinvigoration and not a wake.

Let us then, in 1976, salute the future of the Declaration of Independence, at the same time that we join in venerating and celebrating its past. As Jefferson wrote, not long before his death, "Nothing then is unchangeable but the inherent and unalienable rights of man."

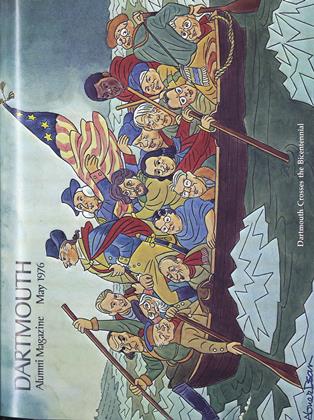

In the 19th century there pouredforth a small ocean of illustratedbooks, mostly for school children,depicting "stirring events" from theRevolution. Mixing fact and fictioninto a fine mythic broth, they alsoserved generations of Fourth of Julyorators, and no doubt their impact onthe nation's consciousness lingers tothis day. Even then perhaps especially then - the United States wasengaged in a search for a "usablepast." Authors and publishers werehappy to satisfy the craving, but werenot above some jiggery-pokery when itcame to sources for their pictures(they borrowed freely from eachother) or, when imagination waned,substituting a view of, say, Braddock's1755 retreat in Pennsylvania for a"stirring scene" of the battle of Monmouth. The pictures accompanyingthis article are from a historypublished in New Haven in 1829 byone J. W. Barber. The book is part ofthe Class of 1926 Collection in BakerLibrary.

New-York

Baţle at Saratoga

Connectient

Patrum's escare at Horseneck

New York

Storminy of Stoney Pond

New-York

Captare or Andre

Virginia

Surrender of Cornwallis

Massachusetts

Battle Bunkers Hill

Maanchusetts

Wanshington of Goverment

New-York

Statue of George III. demolished

New-Jersey

Battle of Trenton 1776

New-York

Marder of Mies Micrea

New-York

Gen Washington leaving New York 1783

Arthur Wilson, whose biography of Diderot won the 1973 National BookAward in arts and letters, is Daniel Webster Professor emeritus.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

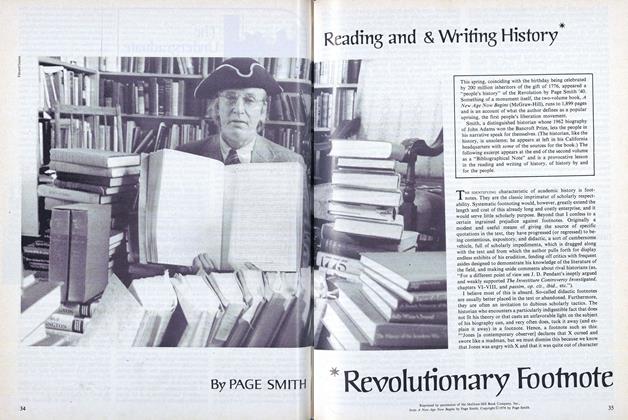

FeatureReading and Writing History and Revolutionary Footnote

May 1976 By PAGE SMITH -

Feature

FeatureWhen Dartmouth Had Its Own State (Almost)

May 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

FeatureThanks to Daniel Oliver, A Gathering of Lovers

May 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleThe Green: A House Mover and an ex-President Proved Who Owns It (Didn't They?)

May 1976 By Jabberwocky, Lewis Carroll, JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

May 1976 By WALTER C. DODGE, CHARLES J. ZIMMERMAN -

Article

ArticleFast Break

May 1976

ARTHUR M. WILSON

-

Books

BooksOUR ARTISTIC WORLD

December 1942 By Arthur M. Wilson -

Books

BooksRAYMOND OF THE TIMES

October 1951 By Arthur M. Wilson -

Books

BooksLA GUERRE D'UN BLEU.

October 1954 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksTHE LITERARY ART OF EDWARD GIBBON.

June 1960 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksHUMAN NATURE AND POLITICAL SYSTEMS.

November 1961 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksPINE LAKE.

MAY 1972 By ARTHUR M. WILSON

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSports Style-Setter

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Feature

FeatureAnd More

April 1975 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTHE THIRD WORLD'S LOW-KEY CRUSADER

JUNE 1990 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureE – i – e – i – o

June 1979 By Marshall Ledger -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO MAKE SURE ALL THE BALLOTS ARE COUNTED

Sept/Oct 2001 By PATRICIA FISHER-HARRIS '81 -

Feature

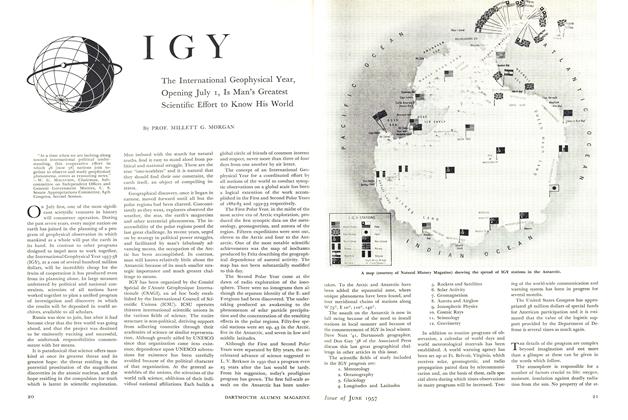

FeatureIGY

June 1957 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN