Love and War among the Ivies

THE AMAZEMENT is — as one turns to look astern half a century or more — not that it has worked out so well but that it ever came into being. Like the English Constitution, the Ivy League exists more in the minds of its organizers than in a set of statute books. It is, in essence, simply a gentlemen's agree- ment among eight consenting establishments of higher learning that all sporting events under their aegis are sporting events — a form of peaceable warfare engaged in by an entirely volunteer army of undergraduates and not by professional delegates. Foot- ball is, in a sense, an acronym for "Ivy League."

My own experience (first as participant, and what seems like forever as commentator) in that most absorbing of American sports, which began on the 17th of September in 1914, made me at once aware that there were then, even on the rosters of prestigious preparatory schools, rather a few professional delegates. What an Age of Innocence. And yet, playing-for-pay football was beginning its commercial career; playing-for-pay tennis, golf, basketball, soccer were to follow. (Professional baseball had been on hand for many a year, though it had not yet begun its proselytizing for undergraduates. Scouts then were not booking agents; they were simply young men, like oneself, who went about looking at football as it was played at neighboring schools and turned in a precis to their superiors. And what in professional baseball, we all thought, could have been more stirring than, at the beginning of the twenties, watching Princeton and the University of Vermont go 15 innings before a single run decided the issue?)

The volunteer army was so small, the undergraduate body itself was so small, that when our elected few took the field of battle against Yale or Brown or Cornell we looked upon them and knew them all; they were not encased in the interstellar head cages that now adorn their successors. And there were not so many faces to be recognized; a player taken out of action in the first half of a match could not go back in until the second half had begun; and a player taken out in the second half was gone for the day. "Playing both ways" (defense and offense) was expected of a man; the barefoot soccer kickers from Nigeria and Uttar Pradesh were still living in their native hutments instead of making fitful appearances on our fields of battle.

It was, after all, Our Game - an undergraduate game invented, we with some reason believed, by the Big Three (Harvard, Yale, Princeton) — and we intended to keep it Our Game. In truth, it was The Game; undergraduates picked up pin and prom money by dispatching daily accounts of afternoon practice to such impressive clarions as the New York Times; the last edition of the Saturday-afternoon Sun was largely devoted to "Blair through centre for six yards; Wickersham around end for fourteen," and the like for every Ivy League game within reach. The Herald Tribune, the Sunday after Yale met Harvard, ran Heywood Broun's report on the event on its front page. Saturdays, Westbrook Pegler desisted from his witty and literate polemics against all evidence of anti-imperialism by ascending to the press box of many an Ivy League match, his black bowler (not then, or now, standard equipment in press boxes) making him easily identifiable. (William F. Buckley Jr., his logical successor, could do the same for us today.) And so few were the substitution of players that the Sun could faithfully list them all.

But it wasn't as Ivy League as we thought it was, either. Brown and Princeton and Columbia and Yale and Cornell and Harvard and Pennsylvania and Dartmouth weren't playing the round robins they play today. Whatever push there was to the notion of all swearing an oath of perpetual fealty dimmed perceptibly exactly 50 years ago, when Harvard and Princeton agreed to disagree and stop playing football together. (An aggrieved Harvard groundskeeper said to me that it cost $11.33 to replace every torn-down set of goalposts, but that must have been only a peripheral reason for the break.) Those of my own random notes snatched from the winds of time remark that in the twenties Pennsylvania was entertaining California at home, that Yale (and its Albie Booth) were visiting Georgia, and getting themselves beat, that Princeton (its Team of Destiny, the caption read) was beating Chicago. As late as 1933, when Reggie Root, a Yale performer of note in his day, suggested that an "Eastern conference" be established, the Ivy League was random indeed, still wandering far outside its confines into a world rarely as idyllic as we wanted our own small Ivy-adorned world to be.

Then, in 1934, the detente (that word is not in my notes) between Harvard and Princeton came to an end, and there was further encouragement; to wit, having parted company 30 whole years ago, Yale and Columbia began to meet again that fall. It was not enough. Ivy League football had begun its Age of Innocence career in exemplary manner: a butterfly life of no more than seven matches, certain agreements not to scout one another's stadiums, a certain rigidity about rehearsal time and the scholastic aptitudes of the volunteer military. Other institutions, other mores. Columbia, a minor miracle of its own making, did journey to the Rose Bowl and upset Stanford, but other excursions outside the league went not as well. Army and Navy, both skilled performers, and both welcome visitors to the league, could match the best of its players, but Douglas Mac Arthur, then superintendent at West Point, was asking Congress for another 600 cadets, and adeptness in athletics is a primary Army consideration. And, in a few years, Army, too big by a mile for anyone else's britches because of the approach of the Second World War, could field four separate offensive units against a terror such as Notre Dame and run up nearly 50 points.

Yes, in 1939, Cornell did put away, with the aid of the matchless Matuszczak at quarter, a rampant Ohio State, but at other moments Dartmouth and Harvard had gone to the Coast (Harvard partway by air, as a novelty) and been demolished for their pains. Swiacki at end, Rossides at quarter for Columbia, did nip Army, triumphant in 32 matches in a row, in 1947, and Pennsylvania tied Notre Dame in 1952. In 1946, Minisi, Pennsylvania's great running back, who had earlier on beaten Navy, returned to his alma mater, after having beaten Penn when he was in the Navy, and beat Navy. And we find Martin, of Princeton until he was likewise abducted by Navy (anything goes in time of war), never going back home but ending up as head coach at Air Force. The disarming of the league's volunteer army by the demands of the nation's military had its effect on league fortunes; so, too, did the newly noticed disinclination of those who had done excellently well in their prep-school varsity days to carry on, once they had become Ivy-clad, through a varsity season, now up at nine games, against a number of outsized opponents. The alumni associations in the Great Outback were getting what they wanted — a showing of the flag in their territory — but it was not at all so certain that the undergraduates and the university administrations were.

In 1952, the Ivy League was constituted — 1952, the year in which Pennsylvania was well enough armed to hold Notre Dame to a tie and to put paid to Princeton's record of 24 triumphs in sequence, in which Pennsylvania was next to embark upon a season in which the only Ivy comrade it was to meet would be Cornell. A year later, when Pennsylvania was beginning to compile a record of consecutive losses that occupied most of three seasons, the league entered into a modest compact that would have every member meet every other member at least once in every five years, and the big outsiders — the Army, the Navy, the Georgias and the Wisconsins and the Notre Dames and the Michigans — began to disappear from the league's order books. "Deëmphasis" was the phrase of the day; Harvard went as far down the scale of values as Davidson and Ohio University. Old school ties were undone in the process; Pennsylvania and Cornell no longer ended their season together, on Thanksgiving Day; Princeton was no longer ending its season with Yale. But the league members are together again, year upon year, and outside partners, such as Army and Navy (no longer swollen by wartime manpower priorities) are again likely outside partners. The patient is again in a state of health (though not quite of wealth) and is again engaged in the pursuit of happiness.

WHAT was it like, so long ago? The landscape that stretches away before my window for 62 years is here and there beclouded, but there are things one recalls with clarity. Line play was the essential, though the forward pass was in existence; my first one, thrown by a prep-school comrade, came to me in 1914, and it was caught while two much shorter players clawed at my midriff. That would have brought on a penalty for them today. Indeed, the general disfavor with which the pass was regarded ("It is counter to the real purposes offootbaW," people were saying) is quite in opposition to the glee with which it is now acclaimed; successive alterations in the rules may even have made the pass an over-protected industry. There was a proposal in the twenties that more than two incomplete passes in a series of downs would draw a penalty of five yards for each failure. This may have become a rule; a few of us centenarians can remember seeing the penalty exacted, though a search of the textbooks offers no confirmation. At all events, until 1934 a failed pass into an end zone meant loss of the ball.

Other landmarks in the progress (on the whole) of the sport come to mind. This observer saw his first lateral pass in 1930 — probably a direct descendant of what went on in matches between Dartmouth and McGill, of Montreal — half under our rules, half under Canadian rules. That same year, he saw his first double wingback, his first spinner. In 1931, he saw his first quick kick — a Harvard novelty. In 1934, he saw his first roving center — Princeton's Callahan — and his first attempts at scoring two points after touchdown — by both pass and line buck. In 1934, still learning the game, he discovered that pass receivers often did not turn around to catch passes until after the ball was thrown — "smart work," he noted, as Holland of Cornell baffled his pursuers. (The pass game was becoming bold as brass.) In 1936, he saw his first end-around, tackle-around, guard-around maneuvers. In 1938, Macdonald of Harvard afforded this spectator his first glimpse of the deep reverse. In 1946, he saw his first mixture of wingback and balanced T — Harvard's. But this recital of Ivy League football's efforts to present a sport in which wit can outmatch weight does not at all evoke the excitement, the delight, that each new sample of trickery created in the eye of the beholder. A few years later, as the rules about substitutions were swept into the dustbin, he saw — everywhere — the first evidences of the now universal platoon system, and football became completely another game.

No more would we see, as we did in 1934, a match in which 11 literally matchless performers (there was no one on the bench of like rank) go an entire afternoon, offense and defense both, against a supernal team chock-a-block with talent and hold it to no score at all — Yale 7 (on a Roscoe-to-Kelley pass), Princeton O. Once, the rules had been devised to hinder a steady flow of substitutes; now a player, after — it has to be assumed — carrying a message from ringside to quarterback, could filter on or off field after every play. It could justifiably be remarked that at this point football had become almost completely a coaches' sport; the time when an improper substitution could cost a cherished time-out had passed, and the time of the specialist punter, blocker, runner, or whatever — put in for a special maneuver that would be needed perhaps but once in an afternoon — had arrived. The platoon method is in its thirties now; the arguments against it — the principal complaint was that a player was no longer an all-round athlete — have been forgotten; the vast ordeal of official bookkeeping (to insure that a performer who could not legally return to a game did not return) came to an end. But if athletics-for-everyone instead of for a few is deemed to be a proper part of undergraduate life, there can be no real regrets.

None of all this was special to the Ivy League. The rules of the road that have set it apart from the rest of the football domain are its unwillingness to make use of athletes who are not in the true sense students, its unwillingness to indulge in spring practice, its unwillingness to play freshmen on the varsity. In so doing, it has painted itself into a corner — not a "coffin corner," to be sure, but nevertheless a corner, and the choosing of playmates from the outside world for league teams is a problem that is bigger every season. In a hut hidden deep in the Black Forest, a set of strategists has been seeking solutions; the first effects of this are apparent in the league's schedules for this fall.

Even before the Ivy League conceded that it was the Ivy League, football was largely a private affair. The annual raffle for any game of importance sometimes allotted so many seats to alumni (all of whom seemed annually to complain about the viability of the seats they were allotted) that not all the underclassmen who wished to view the event could be accommodated. Some of us journeyed to our chosen battlefields by automobile; my own notes of the twenties and thirties indicate that thousands of us arrived in private trains, often with dining cars and almost always with parlor cars. When Dartmouth went to the Coast around Christmas time, it traveled in a train of its own, halting now and again for a session of impromptu practice. It was not enough; Stanford won, handily, but at least Dartmouth had made a royal progress to the Pacific. The Sunday after Yale or Princeton had visited Harvard, the New Haven Railroad ran a second section of the Merchants Limited from Boston to New York — eight parlor cars, two dining cars, these last offering up Cape Cod oysters on the shell.

But my duties as constant observer took me elsewhere as well — to open fields in New Jersey suburbs where spectators stood on the sidelines (there were no grandstands yet) to watch graduates of Syracuse and Rutgers and whatever play football for $50 or $100 a man, to nearly empty stands at Ebbets Field, in Brooklyn, and at the Polo Grounds, in New York, where events of precisely the same sort were taking place. Professional football was on its way, 50 years ago, and the audience it drew eventually filled stadiums just as full as Ivy League stadiums had been filled.

At the same time, a sort of cross-fertilization began — influx of a new form of spectator; efflux of not a few alumni to the professional stadiums. It was soon possible to notice, at Ivy League of events, a new cast of characters — of men who theretofore had come into my view only as the padrones of after-hours establishments and of secret distilleries and breweries, of men known to me theretofore only as bookmakers and betting commissioners. The league had gone public in a quite special fashion. It was The Great Gatsby brought to life. In a way, the league went even more public when, in the early thirties, loudspeakers began to inform the customers what was happening onfield. The performers themselves went more public in 1941, when it was ruled that the haphazard system of enumeration that had prevailed for a number of years would be succeeded by a system that indicated the position every player was to hold down. In December of that year, the United States was at war again.

Next year, many of the putative athletes and putative onlookers were overseas, and those who were still at home were a polyglot lot. In 1943, 30 of the 40 Princeton men who went up against Pennsylvania were sailors or Marines in training on campus; 31 of the Penn men were of the same category. Nighttime football came into the league when Navy played Cornell in - of all places! — Philadelphia. Teams bearing such names as Sampson, Great Lakes, and North Carolina Pre-Flight sprang up, all of them armed-forces enterprises. Scarcity of gasoline, the complete obliteration of special trains created rows of empty stadium seats, some of them never to be filled again. (The brave little fleet of open-air trolley cars that paraded on Saturdays from the railway station in New Haven to Yale Bowl survived until 1945.)

What had once been a steady supply of preparatory-school players dwindled; the press releases proclaiming that 26 prep-school football captains would be part of the fall's freshman team ceased; what skilled performers accrued to the league arrived now mostly from high schools; and on-campus movements that put down such extracurriculum activities as football and opted for notions more transcendental got under way. In 1953, Harvard embarked upon its experimental period of "dëemphasis." By 1956, all the league teams were for the first time playing all the others; the league had retired into its shell (depending upon who is speaking) or its norm. And so it has remained.

Ivy League football survives. The on-campus denigration of the sport has in some quarters succumbed to a new undergraduate enthusiasm, and there are still alumni whose Saturdays as well as whose Sundays are assigned to visiting stadiums. The sun of television, it is true, rarely shines on the citadels in which the sport began; Ivy League football, it is said (and that, too, is true) is behind the times: i.e., its teams are not put on probation; its coaches are not allowed to "resign" because of violations of the rules of honor; its assistant coaches do not barge about through high-school records and get them improved so that students of niggling attainment can play varsity football before midyears examinations remove them from the roster. Its players are neither sequestered from their classmates nor the beneficiaries of special privilege; they are of, by, and for the un- dergraduate body. So be it.

The author: Rogers E. M. Whitaker, Princeton '22 and NewYorker '26, says, "I became a sports writer 40 years ago so thatsomeone would pay me to go by train to universities in theeastern part of the United States and report on their wintersports."The operative word is "train." Readers of the world's greatestmagazine (let's be honest about it) know that Whitaker has morethan a nodding acquaintance with E. M. Frimbo, the world'sgreatest railroad buff; the old curmudgeon (the o.c.), gruff commentator on the important things in life like restaurant service;and J. W. L., autumnal haunt of places like Palmer Stadiumand Memorial Field.Given the state of today's rail service, J. W. L. is limited tovisiting one stadium per Saturday. But a variety of sources, in-cluding girl friends of some players, supply information for hisweekly reports on Ivy games. "You sometimes learn more fromgirl friends than the coaches," he says.

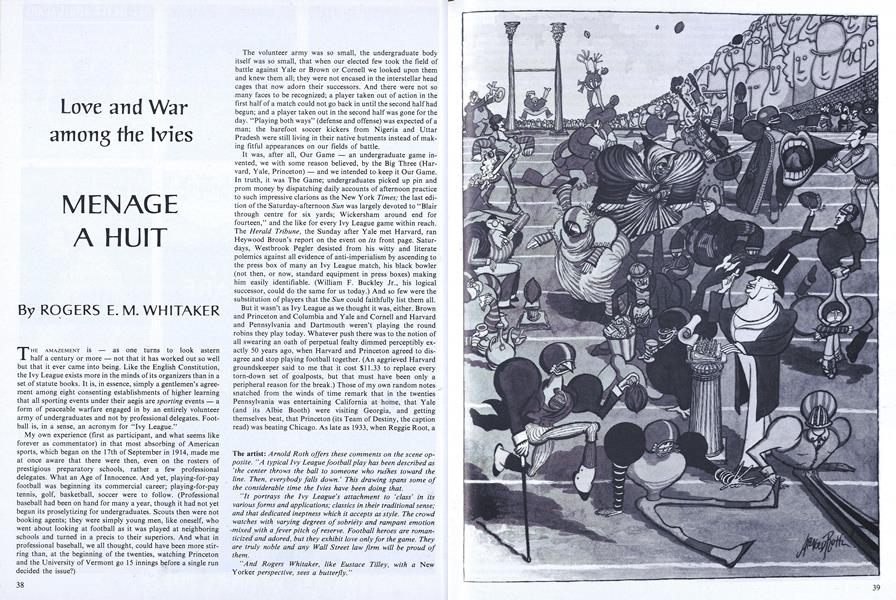

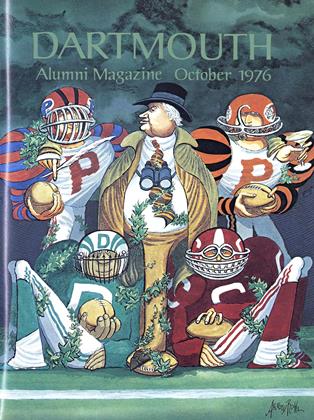

The artist: Arnold Roth offers these comments on the scene opposite. "A typical Ivy League football play has been described as'the center throws the ball to someone who rushes toward theline. Then, everybody falls down.' This drawing spans some ofthe considerable time the Ivies have been doing that."It portrays the Ivy League's attachment to 'class' in itsvarious forms and applications; classics in their traditional sense;and that dedicated ineptness which it accepts as style. The crowdwatches with varying degrees of sobriety and rampant emotionmixed with a fever pitch of reserve. Football heroes are romanticized and adored, but they exhibit love only for the game. Theyare truly noble and any Wall Street law firm will be proud ofthem.

"And Rogers Whitaker, like Eustace Tilley, with a New Yorker perspective, sees a butterfly."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE IVORY FOXHOLE

October 1976 By JEFFREY HART -

Feature

FeatureRED BALLING IN THE JERSEY NIGHT

October 1976 By Jeffrey Brodrick -

Feature

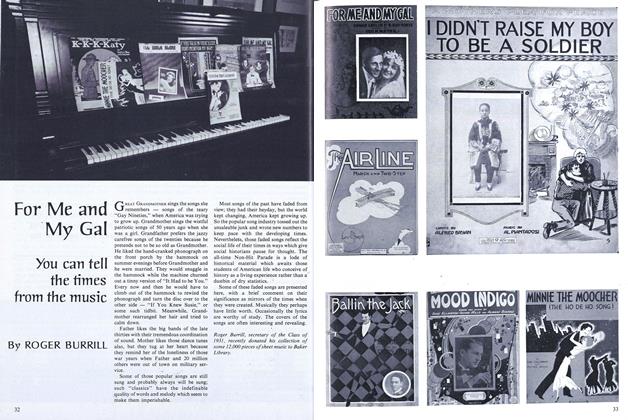

FeatureFor Me and My Gal

October 1976 By ROGER BURRILL -

Article

Article'My Own House'

October 1976 By ALLEN L. KING -

Article

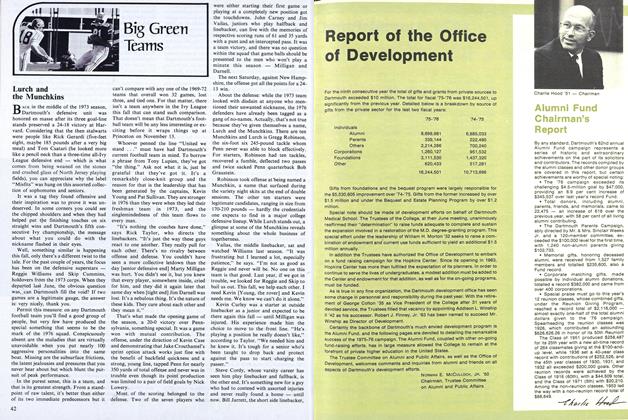

ArticleAlumni Fund Chairman's Report

October 1976 -

Article

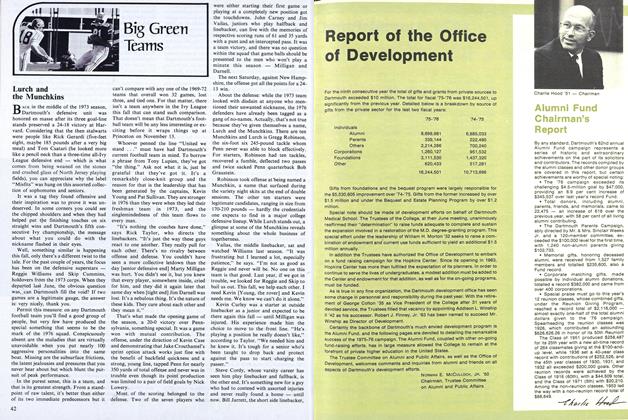

ArticleLurch and the Munchkins

October 1976 By JACK DEGANGE

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHANOVER SUMMER

September 1976 -

Cover Story

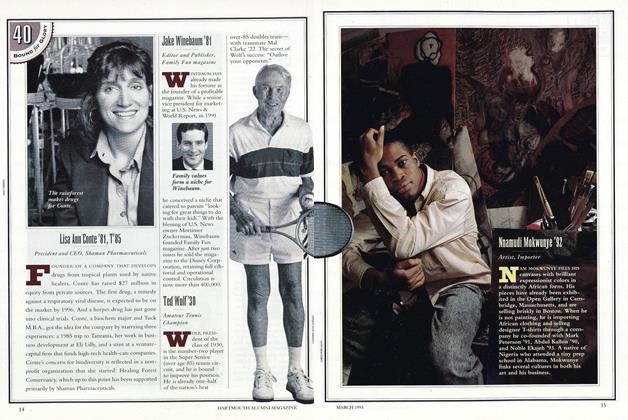

Cover StoryNnamudi Mokwunye '92

March 1993 -

Cover Story

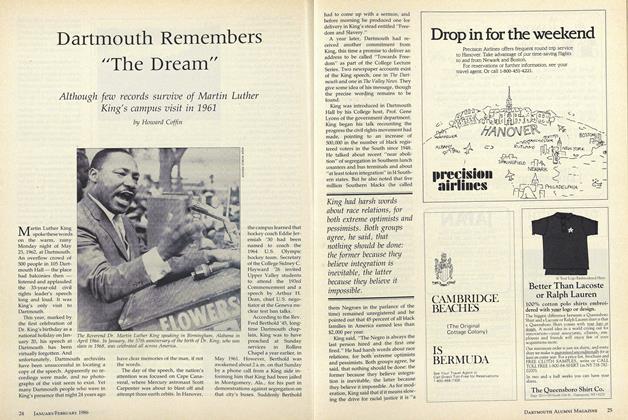

Cover StoryDartmouth Remembers "The Dream"

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1986 By Howard Coffin -

Feature

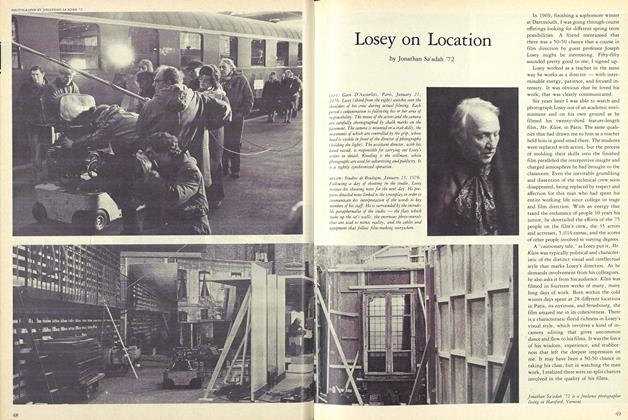

FeatureLosey on Location

November 1982 By Jonathan Sa'adah '72 -

Feature

FeatureFirst

MAY | JUNE 2016 By Judith Hertog and Lexi Krupp ’15 -

Feature

FeaturePost What?

DECEMBER 1998 By Karen Endicott