Where do I begin...on the heels of Rimbaud moving like a dancing bullet thru the secret streets of a hot New Jersey night filled with venom and wonder. Allen Ginsberg

Jeffrey Brodrick, a senior from Weston,Massachusetts, says "redballing" is a termused by old ambulance drivers to describetravel at high speeds, with lights and siren.After living and working in Jersey City forthe past year, Brodrick recently quit hisjob to travel and return to school. He andhis godfather currently are heading Weston their ten-speeds, with an ultimatedestination of Hawaii.

THE siren wails, echoing off the pavement. Taking the overpass at 40 the flashing lights are almost stroboscopic; casting splotches of red onto the bridge and sidewalk, they stain the cement with an odd poetic light, a soft muted red that lasts only a moment.

Half asleep, I slide into the seat, listless. "What do we got?" It is Mohlman's turn to drive. "Motor vehicle accident, Tonnele Circle. Supposed to be trapped inside. Could be a good one." Mohlman is small, gray haired, intense. He runs red lights foot-to-the-floor, a madman behind the wheel, deep into his art. I begin to wonder just what has happened, and realize it could be something big. My throat gets a little dry. Ahead is a burgundy Mercedes wrapped against an abutment. Inside is a woman, hysterical, confused. She asks us what happened, then asks us not to let her die. She is trapped inside and cannot move. It takes the police half an hour to rip off the door and take enough of the car apart so we can get in. It is apparent the woman is seriously injured. When they lift her out of the car I stand waiting with a sheet and a splint. I know that I have a second to act, to lunge and catch her foot — before it falls off. In the ambulance we do our best to splint and dress the unearthly number of fractures. But what is crucial is the unseen damage, the internal injury. That night I awake to find myself half out of bed, lurching to grab something, and with a shudder I remember the accident, and the woman's splintered body, and rushing to catch it before it falls apart. It is not for several days that she dies.

It was late last winter when I got a job as an emergency medical technician, working out of the ambulance garage at the Jersey City Medical Center. I had been interested enough in medicine to sleep through several terms of chemistry in Hanover; ambulances were a dream, of basic, almost elemental work, of living and dying, where there was something to be done and you had to do it. It was a dream, distant and impossible, something you read about; it was like a world you had to be born into. In the fall I lived in an attic and took an 81-hour course to become certified to work on an ambulance. I studied enough to get by, as much as I would study anything out of a book. In January I went to Jersey City under the auspices of the Tucker Foundation. Two months later, around midnight, I was in the Seagull, a sleazy neighborhood bar, talking long distance to a friend, saying how I had got this job, driving an ambulance, in Jersey City....

The times were unreal, exacerbating, exacting, comical. Engrossing.

Medicine was what interested me, and what I expected; the people were unexpected, ludicrous, trying, fascinating. There were a few basic skills to be mastered, taking pulses and blood pressures, performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation, splinting and bandaging, and driving, at high speeds; but all this had to be performed while the patient was drunk, or cursing you, or amidst a moaning, sobbing family, or worst when you had to fight to keep from laughing, and a straight face was an ordeal. People.

THE garage becomes the center of my existence. I work the eight hours from four to midnight, when the sun goes down and the city comes up swinging, relentlessly engineering its own destruction. I seem to spend my life at the garage, where seven ambulances were once housed and the drivers carried guns. Its elaborate marble floors evoke another day, an entire era, the colossal decadence of this medical center begotten of corruption, a political gift from Roosevelt to the mayor of Jersey City. It is a vast place, sprawling with 20 story buildings and underground tunnels and indoor swimming pools. Once considered perhaps the finest hospital complex on the East Coast, it is now crumbling financially and structurally, the buildings abandoned or in disrepair. The city is worse, a miscarried metropolis, an urban nightmare of glass-strewn streets and dilapidated, burned-out buildings still peopled — the insides dank, ruinous.

More than a quarter of a million people live in this city, whites, blacks, Spanish, each group with its own plague. PRS is an acronym denoting Puerto Rican Syndrome, the Spanish proclivity for anxiety. Misinformed teenagers solemnly recite to me their improbably precocious disorders. "I have a bad heart. The doctor, he told me, I had a heart attack when I was 12." "Were you in the hospital?" "No." Collectively, this is a sick city, pathological in its inability to care for itself. Many of the calls are routine sick calls, although when we arrive the people are convinced they are dying. Unable to distinguish between minor ailments and those which threaten their lives, they consider every problem a crisis, and call an ambulance. "Where you been man. Come on. He could be dying. Jus' take your time, while he be dead." The object of such concern writhes on the sidewalk, spasmodic movements artfully produced to highlight the presence of great pain. There proves to be nothing wrong with him; his gyrations a mere practice ses- sion, a public workout he is throwing to the burgeoning crowd.

I learn to deal with it, to differentiate between what is real and what is not, in a variety of wild and improbable situations.

One night we are called to a car accident, and come upon a blue Thunderbird swallowed up by the pavement. There are no patients to be found. The cops lead us to the bar on the corner, where the "perpetrator" is known to be located. Inside is a peroxide blonde, thirtyish, downing shots of whiskey. "Take my pressure!" she screams, motioning to her heart. "It's rheumatic. Take my pressure!" "Take her to the hospital!" orders her burly escort, oozing authority and machismo. "Why don't you both just shut up," says my partner, settling the issue to my satisfaction. A minute later we split, the woman assured that her "rheumatic" heart is going to make it through the night. Tough guy is still frothing at the bar, muttering that if we don't shut up, we'll need an ambulance.

The phone rings, and all that can be heard is a woman screaming, then silence. The operator traces the number, and gives us an address. In pouring rain we arrive at a dark, seemingly deserted house. We knock for a minute and no one answers. Then we open the door. A few children are huddled in the front room, but they're not talking. "Where's your mommy?" Silence. A dim light towards the back. We turn to leave, when I notice, in the kitchen, a phone off the hook. The cord is stretched taut, into another room, stretched taut it disappears into darkness. In the darkness we find a woman who weighs maybe 300 pounds and is seven months pregnant. And she is having contractions. "Somethin's wrong," she moans. "Never been like this before. Somethin' wrong." Eight hours later she is dead of a ruptured uterus.

Spring evaporates into stifling summer. I learn to sense a situation and know if it is serious, to look at a man and see that he is dying. The first month I seem to be on every cardiac emergency called in. One week straight every night I hit OD's: a washed up Vietnam veteran sprawled in the bathroom with a bloody needle in his arm; a strung-out hipster type; a 15-year-old Spanish kid who is messing with heroin and has gotten in a little over his head. We find him at the bottom of some stairs, in a dark cellar, and he isn't breathing.

I become reasonably competent, and confident. I begin learning to drive.

Early in the summer I happen upon one of those magic calls. It is a warm night and we take the ambulance down to the stadium, to hang out at a rock concert. We get preferential treatment. A large gate is opened and we back the ambulance into a tunnel underneath the stadium. We keep the bus running in case we get a call, and take turns listening to the music, soaking up the scene, the ambiance of the band, the dope, the teenybopper girls. I return to the bus to hear the radio sputter, "A-36 you have a call. It's a rush. At the stadium, gate 6. A cutting." Showtime.

I flip on the lights and the gate swings open. Like a pent-up bull we charge out. People scatter out of our way. The siren yelps. Thirty seconds and we are on the scene — a bunch of cop cars and motorcycles thrown into this park just outside the stadium. A grove of trees and darkness. I don't really know what is going on. My partner gives me a push and tells me to get moving. I start running and follow a cop. It is one of those moments when the night is electrified and time is out of control and you have no chance to think, just act. Your mind just stares. The scene is that deep. The cop is nervous beyond belief and keeps stuttering, "I don't know. I don't know. It's pretty bad. I don't know." I seem to float through the trees and through the darkness.

Ahead is a bunch of people huddled over a figure on the ground. On the ground is a young kid bleeding to death. His bodyshirt is soaked with his own blood. He has been slashed in the neck, and at least one artery has been severed. I can't see how we are possibly going to stop the bleeding. It spurts at least a foot. My partner restores a momentary loss of calm. "Okay, we'll just take a look, take our time." After a

wavering instant I feel utterly relaxed. In control. I even have to pacify the cops. I think they expect us to operate or something. There is nothing to be done except apply pressure on the wound until we arrive at the hospital. That and treat for shock. The kid is drunk, semi-conscious. When he starts cursing me I figure he's going to be all right. When we arrive at the hospital the bleeding is controlled. After we wheel him down to the ward the drama subsides, and suddenly it is all too much and I feel like getting out, so I split. He only has to be operated on and the blood vessels tied off. I walk back down the corridor, my whites stained with blood, feeling like a bullfighter, like I'm coming out of some great epic.

Back at the garage I change my uniform. The talk centers on how I feel, saving somebody's life. "All that equipment, and what it took was two fingers. You feel all right, huh?" Yeah. ...

The next day I come to work early to hang out and savor my feelings. The afternoon sun cuts across the great amphitheater formed by the buildings and the plaza, a fabulous square of cement and brick. Last night — without any reflection you know it is great. Saving somebody's life. You don't even need to think about it to feel good. But the first thing I hear when I arrive is how everyone is talking about how the mayor is on the phone every hour and this is going to be a very, very big deal politically, and the kid was in the operating room all night and again this morning and they can't stop the bleeding, and he's going to die, if he isn't dead already.

It all goes down the drain. It was like a chance for something perfect, and just when the curtain was closing, something went wrong and the whole scene collapsed. The bleeding was never stopped, see. Maybe externally. All along he was hemorrhaging internally from a jugular vein and two carotid arteries. It all fades out, a failure.

So I make concessions, look for subtler reasons. Behind the wheel of that ambulance I see a city, staggering hypnotically; I see bums who have been existing on the streets, marginally, for years, aged men with gray, greasy hair and florid alcoholic skin who reek of liquor and vomit and the filth of their decaying bodies, old men who keep calling you "Doc" in tones of reverence, packing an endless pint of bourbon on their hip, and with it, a vow to quit the bottle; I see young children left alone in a filthy apartment with no one but the rats to take care of them, the cockroaches preoccupied, dancing on the walls as if to some upbeat disco; I see a hundred cars smashed up and I see someone gunned down, shot five times in the back; I cruise up Ocean Avenue in the neon night and see a thousand bars and a thousand people and I come upon a million stories; I see someone die, before my eyes, an old black man of 84 takes his last breath, before my eyes he fades away; I even see someone born. I learn much about medicine, people, and I get a chance to see some beautiful girls. Ask me what it means and I will tell you nothing, though in a detached moment I see it all.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

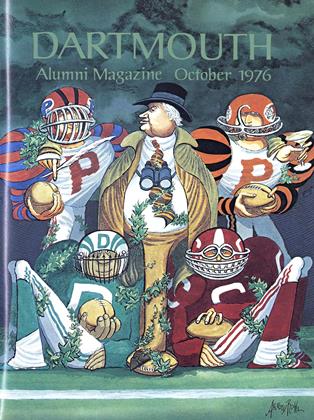

FeatureTHE IVORY FOXHOLE

October 1976 By JEFFREY HART -

Feature

FeatureMENAGE A HUIT

October 1976 By ROGERS E. M. WHITAKER -

Feature

FeatureFor Me and My Gal

October 1976 By ROGER BURRILL -

Article

Article'My Own House'

October 1976 By ALLEN L. KING -

Article

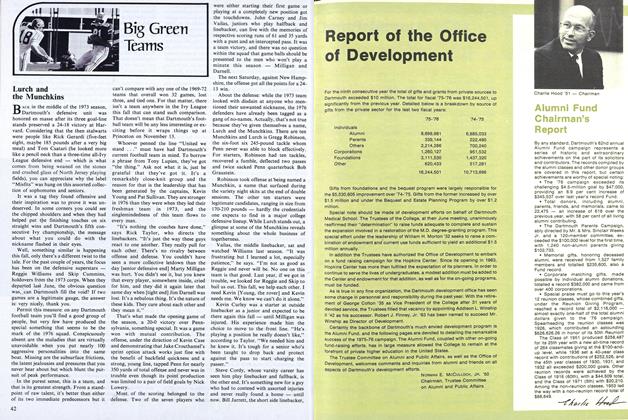

ArticleAlumni Fund Chairman's Report

October 1976 -

Article

ArticleLurch and the Munchkins

October 1976 By JACK DEGANGE

Features

-

Feature

FeatureENGINEERING SCIENCE

May 1958 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July/August 2008 -

Feature

FeaturePutting Words in the Mouths of the Great

December 1989 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Nov/Dec 2000 By JOE MEHLING '69 -

Feature

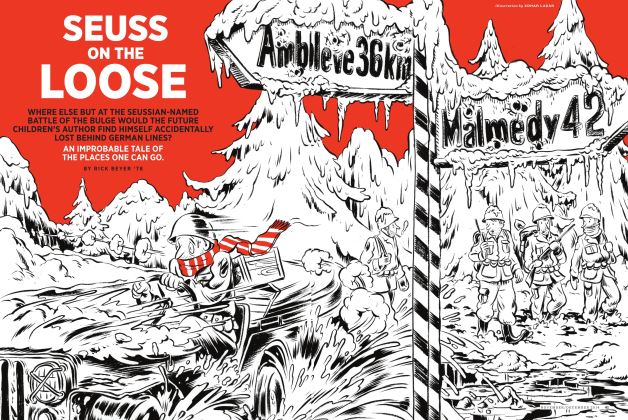

FeatureSeuss On the Loose

NovembeR | decembeR By RICK BEYER ’78 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/August 2005 By Thomas Vieth '80