CONVOCATION was held in the early 1970s in Webster Hall, the classical brick structure on the periphery of the Green. Last year, the sardine-can atmosphere of the old hall finally became intolerable and the site of the ceremony was changed to the gym. Last month, as the College opened for its 207th year, Convocation was again moved, this time to the Rupert Thompson Arena.

The proceedings took up half of the concrete floor of the arena. The other half was used to set up for the 150 gallons of cider and 3,000 doughnuts that would be consumed afterward. Last year, when Convocation was held in the gym, "cider and doughnuts," as it is called, was mysteriously omitted from the program. The students raised hell. This year, Ralph Manuel, the dean, was mildly apologetic. "Four out of five is pretty good — that's an .800 average," said the former varsity baseball player at the beginning of his remarks. "On that note let me say that for the fourth time in five years, we'll have cider and doughnuts."

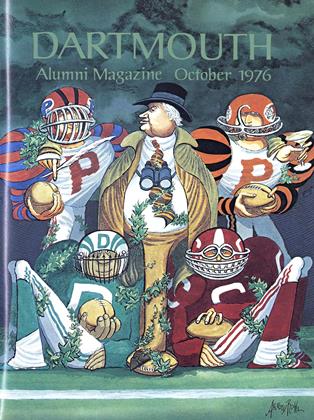

This fall, the polemics center on the enduring dispute over the College symbol and on the placement of a large iron sculpture by Mark di Suvero, entitled "X Delta," on the lawn near Sanborn House. A group of compromisers recruited a towering, swarthy fellow to tote an axe and wear a wool shirt and suspendered pants at the football games. They want to determine whether the students would approve of the Woodsmen as the College symbol. So far there is no concerted movement to adopt the woodsman or the Woodsmen. The cheer "Dart-mouth! In-dians! Scalp 'em!" still emanates from the Memorial Field stands. The sculpture, a gift from an alumnus, was defaced with green paint shortly after classes began. Students have complained that the iron monster has diminished the atmosphere of green grass and trees and red brick and white trim.

Symbols are important reminders of the past. But I can't help thinking that the many recent discussions about traditions at the College have in some way hindered our sense of place, our sense of the past and the future. We are today forcing tradition on the College. In fact, many Dartmouth traditions are illusory or incipient: the Indian never was officially declared an insignia of the College; cider and doughnuts, that "long tradition," was first held five years ago.

What has come to be known as the Dartmouth mystique is intangible and has nothing to do with cider and doughnuts or the hucksters' wares — Dartmouth cigarette lighters, beer mugs, and baby pants — or even the aesthetic wholeness of the lawn area adjacent to Sanborn House. The Dartmouth mystique is a state of mind, and it is reaffirmed each year by one of the College's greatest traditions: Convocation. The ceremony takes place at a time of new beginnings, just as the warmth of summer is melting into the protean moodiness of another New England autumn. The student population, sundered in two during the summer term, is, for the most part, together again. There is the regenerating presence, the infectious spirit of more than 1,000 pea green freshmen.

For students, I think, the most memorable Convocation is that of the freshman year, for that is when the legacy is passed on to them. I haven't forgotten my freshman Convocation, two years ago, the last to be held in Webster Hall. "Dartmouth," said Dean Carroll Brewster, who was making his last Convocation address at the College, "has since its founding remained as committed to the nurturing of your conscience, the animation of your spirit, as it has to the cultivation of your intellect .... " He told his audience that wisdom, spiritual growth, and good judgment should be their goals. He quoted Ernest Martin Hopkins, John Sloan Dickey, and John Kemeny. He concluded: "I call upon you to serve the ideals of your college in this hour with all your strength and all your spirit and all your heart."

Those are lofty ideals for an era in which ideals are not universally fashionable. They are ideals that must be protected if they are to remain a part of the Dartmouth tradition. And they are the same ideals that were reaffirmed for the 207th time last month. John Kemeny told students that the "greatest rewards" of a Dartmouth education "are not monetary, but intangible — the arousing of curiosity, the satisfaction of a thirst for knowledge and helping students to become better human beings." Ralph Manuel read a letter written by an alumnus to a brother entering the College: " 'Hold on to what is right . ... Only one person can tell you if you're doing the right thing - yourself.' " "Your college," Manuel said, "will be known by the way you live your lives."

I find myself sometimes flipping to the back pages of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE to read the obituaries that tell about how those who preceded me on this campus by three-score or so years chose to live their lives. For as preoccupied as we are today with the College symbol and other traditions, we should not forget that what is passed on at Dartmouth College is not just an education but an outlook on life. The Kemenys, the Brewsters and the Manuels are not passing on symbols and traditions but pieces of themselves. The Zorbatic Carroll Brewster, who said in a farewell to the graduating class of 1975, "I hope that Dartmouth has touched each of you with the spirit of adventure; the willingness to risk yourself for noble purpose..." himself, upon completing his schooling 14 years ago, spent three years traversing Sudan in a truck and Land-Rover, compiling the country's laws. Last summer, I asked John Kemeny why he had studied mathematics. "Because I love it," he replied. "... If you ever come to an un- derstanding of the beauty that is there, it is a very intoxicating experience." That, if you ask me, has more to do with the Dartmouth mystique than cider and doughnuts.

"Symbols are important reminders of the past. But many recent discussions about traditions have hindered our sense of the past."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE IVORY FOXHOLE

October 1976 By JEFFREY HART -

Feature

FeatureMENAGE A HUIT

October 1976 By ROGERS E. M. WHITAKER -

Feature

FeatureRED BALLING IN THE JERSEY NIGHT

October 1976 By Jeffrey Brodrick -

Feature

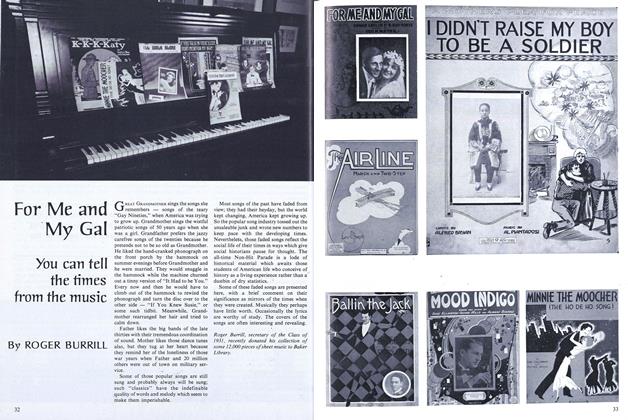

FeatureFor Me and My Gal

October 1976 By ROGER BURRILL -

Article

Article'My Own House'

October 1976 By ALLEN L. KING -

Article

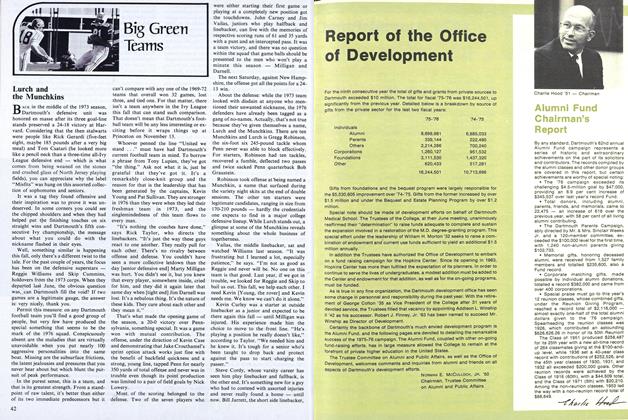

ArticleAlumni Fund Chairman's Report

October 1976