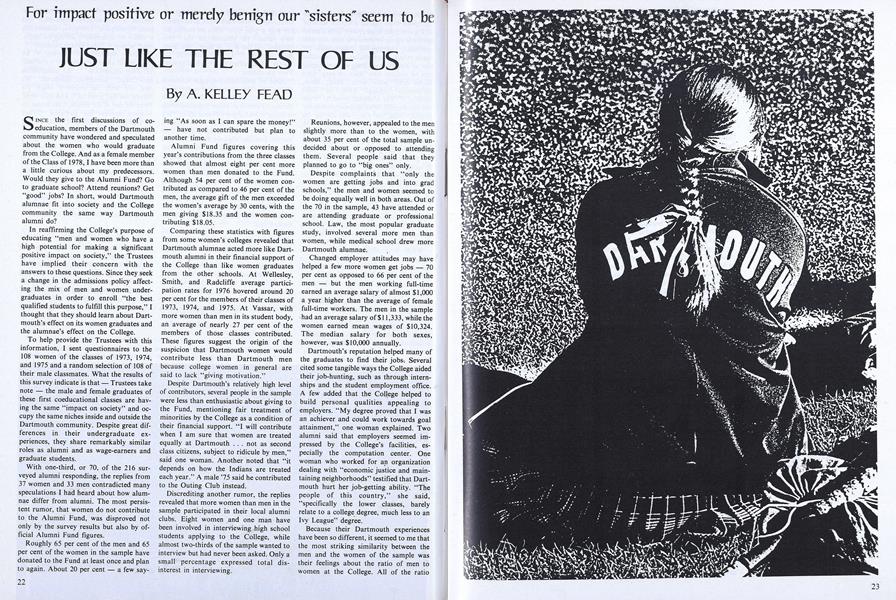

For impact positive or merely benign our "sisters" seem to be

SINCE the first discussions of coeducation, members of the Dartmouth community have wondered and speculated about the women who would graduate from the College. And as a female member of the Class of 1978, I have been more than a little curious about my predecessors. Would they give to the Alumni Fund? Go to graduate school? Attend reunions? Get "good" jobs? In short, would Dartmouth alumnae fit into society and the College community the same way Dartmouth alumni do?

In reaffirming the College's purpose of educating "men and women who have a high potential for making a significant positive impact on society," the Trustees have implied their concern with the answers to these questions. Since they seek a change in the admissions policy affecting the mix of men and women undergraduates in order to enroll "the best qualified students to fulfill this purpose," I thought that they should learn about Dartmouth's effect on its women graduates and the alumnae's effect on the College.

To help provide the Trustees with this information, I sent questionnaires to the 108 women of the classes of 1973, 1974, and 1975 and a random selection of 108 of their male classmates. What the results of this survey indicate is that - Trustees take note - the male and female graduates of these first coeducational classes are having the same "impact on society" and occupy the same niches inside and outside the Dartmouth community. Despite great differences in their undergraduate experiences, they share remarkably similar roles as alumni and as wage-earners and graduate students.

With one-third, or 70, of the 216 surveyed alumni responding, the replies from 37 women and 33 men contradicted many speculations I had heard about how alumdiffer from alumni. The most persistent rumor, that women do not contribute to the Alumni Fund, was disproved not only by the survey results but also by official Alumni Fund figures.

Roughly 65 per cent of the men and 65 per cent of the women in the sample have donated to the Fund at least once and plan to again. About 20 per cent - a few saying "As soon as I can spare the money!" - have not contributed but plan to another time.

Alumni Fund figures covering this year's contributions from the three classes showed that almost eight per cent more women than men donated to the Fund. Although 54 per cent of the women contributed as compared to 46 per cent of the men, the average gift of the men exceeded the women's average by 30 cents, with the men giving $18.35 and the women contributing $18.05.

Comparing these statistics with figures from some women's colleges revealed that Dartmouth alumnae acted more like Dartmouth alumni in their financial support of the College than like women graduates from the other schools. At Wellesley, Smith, and Radcliffe average participation rates for 1976 hovered around 20 per cent for the members of their classes of 1973, 1974, and 1975. At Vassar, with more women than men in its student body, an average of nearly 27 per cent of the members of those classes contributed. These figures suggest the origin of the suspicion that Dartmouth women would contribute less than Dartmouth men because college women in general are said to lack "giving motivation."

Despite Dartmouth's relatively high level of contributors, several people in the sample were less than enthusiastic about giving to the Fund, mentioning fair treatment of minorities by the College as a condition of their financial support. "I will contribute when I am sure that women are treated equally at Dartmouth ... not as second class citizens, subject to ridicule by men," said one woman. Another noted that "it depends on how the Indians are treated each year." A male '75 said he contributed to the Outing Club instead.

Discrediting another rumor, the replies revealed that more women than men in the sample participated in their local alumni clubs. Eight women and one man have been involved in interviewing high school students applying to the College, while almost two-thirds of the sample wanted to interview but had never been asked. Only a small percentage expressed total disinterest in interviewing.

Reunions, however, appealed to the men slightly more than to the women, with about 35 per cent of the total sample undecided about or opposed to attending them. Several people said that they planned to go to "big ones" only.

Despite complaints that "only the women are getting jobs and into grad schools," the men and women seemed to be doing equally well in both areas. Out of the 70 in the sample, 43 have attended or are attending graduate or professional school. Law, the most popular graduate study, involved several more men than women, while medical school drew more Dartmouth alumnae.

Changed employer attitudes may have helped a few more women get jobs - 70 per cent as opposed to 66 per cent of the men - but the men working full-time earned an average salary of almost $1,000 a year higher than the average of female full-time workers. The men in the sample had an average salary of $11,333, while the women earned mean wages of $10,324. The median salary for both sexes, however, was $10,000 annually.

Dartmouth's reputation helped many of the graduates to find their jobs. Several cited some tangible ways the College aided their job-hunting, such as through internships and the student employment office. A few added that the College helped to build personal qualities appealing to employers. "My degree proved that I was an achiever and could work towards goal attainment," one woman explained. Two alumni said that employers seemed impressed by the College's facilities, especially the computation center. One woman who worked for an organization dealing with "economic justice and maintaining neighborhoods" testified that Dartmouth hurt her job-getting ability. "The people of this country," she said, "specifically the lower classes, barely relate to a college degree, much less to an Ivy League" degree.

Because their Dartmouth experiences have been so different, it seemed to me that the most striking similarity between the men and the women of the sample was their feelings about the ratio of men to women at the College. All of the ratio possibilities were supported by almost equal numbers of men and women. For example, 12 women and 12 men wanted an even ratio and five men and five women wanted a ratio of 3:1. Only their reasons for advocating one ratio instead of another revealed their diverse undergraduate lives.

Several women felt that the College should remain predominantly male. Some, as members of a minority, liked being "special." Others thought they made friends more easily among men than among women and felt, as one woman said, that "being at Dartmouth when the ratio was high was the best time." Still others were concerned about losing some of the College's spirit by admitting a greater number of women. "I am persuaded that there is much to be gained from either a school which is predominantly male or predominantly female since it is my experience that these are the schools that tend to develop more integrity and character - more 'spirit,' " one woman noted. She added that women who feel "oppressed because they are in the minority ... and need to change the College to make themselves more powerful or to 'prove' themselves are fighting the spirit of Dartmouth ... and are not welcome there." Another woman opposed an equal ratio because "Dartmouth's maleness has some positive aspects to it - encouraging careers for women who may never have contemplated them, making them struggle to get by in a more male business world, and handling aggressive men academically and socially."

One male '75, who preferred to think of himself as a member of the last all-male entering class instead of a member of one of the first coed classes, wanted to see a ratio of 800:0. "I enjoyed all-male Dartmouth because there was a different atmosphere - the element of competition for females was lacking," he said. A classmate advocated the preservation of "the true historical flavor" of the College, as embodied in a 3:1 ratio, because he felt that equal enrollments of men and women would move the College down "the oftentrod path to mediocrity." Several others echoed his belief that the College would lose its "uniqueness" if it admitted a significantly greater number of women.

Many felt, however, that the College should not have quotas of men and women dictated by a specific admissions policy. "Ratio ... ratio ... ratio ... Little babies don't have to pass a sexual ratio test before they're allowed into human society, so why should there be a ratio at Dartmouth?" one man asked. Others also said they desired a "sex blind" admissions policy with "people admitted on the basis of academic achievement, personal development, extracurricular interests, and intellectual capacity." One woman stated this policy succinctly when she said, "Sex has no place in determining the future enrollment of Dartmouth classes." Another woman set limits to her concept of sex blind admission, saying that no more than 50 per cent women should be admitted into each class.

Between the extremes of sex blind admission and a total exclusion of women from Dartmouth, half of the people in the sample said they wanted more women than currently admitted and proposed ratios of 1:1, 2-1, and 3:2. Ten people said they would like the Trustees to maintain the 3:1 ratio, while 14 advocated sex blind admissions. Only five - two men and three women - desired more men or an all-male College.

Some warned against an increase in the size of the College. One woman wanted an even ratio only if there were no "risk of overcrowding." A '74 noted his disillusionment with Dartmouth when, after returning from a year off-campus, he saw "overcrowding in dorms, in classes, and got a general sense of increased size (i.e., harder to see a dean, more red tape)." He added, "It was to my friends and me as if Dartmouth just couldn't take a thousand more - male or female."

Withdrawal of alumni support of the College was also a fear of several people in the sample. A '75 said that sex blind admissions would "cost too much in alumni support if not enough men were admitted to have a good football team." Others suggested that enrolling more women would jeopardize alumni support in general. "Unless women can break away from traditional roles which tend to discourage alumnae activities on their part," one woman said, "I expect it will be wise for Dartmouth to maintain a maledominated admissions policy."

The alumni and alumnae of the sample criticized the social scene at the College during their undergraduate years. One man spent a year at Smith, which he said helped to "counter-balance" his social life at Dartmouth. Having viewed road-trip-ping as an alternative to coeducation, several men said they had fared better socially with women from other schools than with Dartmouth women. One man noted simply that it was "easier to shop elsewhere." A '73 who recommended sex blind admissions said, "My Dartmouth experience, although remembered nostalgically as a time of fun, skiing, bull sessions, beer-pong, smoking grass, and, above all, innocence, only retarded my personal/emotional development." A woman added that the College taught her "to avoid social relationships with spoiled boys who don't want to grow up and assume responsibility for themselves and their actions." Other voices, other views.

Several men said that their total experiences with coeducation were positive, but most noted that it had little effect on them because of the small number of women involved. "Coeducation was a farce," according to one '75 who asked, "With a 1:15 ratio, how could it have much effect on me?" Another said he had never met a "coed" but that he felt coeducation was "better than walking across the Green at night ... howling at the moon." Many men mentioned that they had made little contact with the women in their classes, but some who did felt that they had learned how to deal with women better. Noting that the Dartmouth women he had known were "certainly not freaks but very real and warm people," one man said that coeducation had made his Dartmouth experience "more enriching and rewarding." Another said that coeducation had given him insight into his male friends, while a '73 mentioned that he had held negative feelings for Dartmouth until women were admitted. One man concluded that coed Dartmouth "makes for a less competitive, healthier, less macho/frustrated atmosphere."

The women expressed widely different opinions about their stay at the College, using words like "agony and ecstasy," "challenge," and "great" to describe it. Most said they had ambivalent feelings about being an undergraduate at the College. "Dartmouth was the best of times and the worst of times," said a '75. "I enjoyed being one of the first coeds, but there was a price to pay." For some, the price was not having many women friends. For others, it was having to play two roles - being "one of the boys" at one moment and in the next, being a WOMAN among MEN. Many were proud, however, to have been pioneers, despite the hardships of being "symbols of change at the College" and "strange new creatures in the eyes of faculty and students."

A large number of women in the sample felt a strong commitment and responsibility to "prove that coeducation is a good idea." One woman said she worked hard to show that she was as qualified academically as her male classmates. Another noted her particular responsibility as an alumna, adding, "At my Dartmouth Club meetings the alums 'boo' when coeducation is discussed and ask my husband if I am a real alum, too." Another woman agreed that not only do alumnae need "to prove that women are valid members of the student body" but also to "provide a role model for women at Dartmouth now."

One '73 wanted her fellow alumni to realize the strength of the alumnae commitment to Dartmouth. Advocating an even ratio, she said, "The College would benefit from initiating this procedure gradually - to prove to these 'doubting Thomases' that the caliber of the women graduates the College is producing is extremely high, and that they, like the thousands of male graduates the College has produced, are capable of showing their support of the College financially and through alumni/alumnae activities."

A few men felt, however, that their female classmates were "special" and not necessarily typical of all women of current or future Dartmouth classes. "My impression of many of the women Dartmouth was accepting initially ... might have been ... women who would most easily fit into the predominant athlete/profraternity set, which probably was a rational policy for the transition period," said one male '74, who hoped that future classes would contain more diverse types of women. Several mentioned unequal treatment of the men and the women by the administration. A male '75 said that the women were "guinea pigs [who] received an extraordinary amount of attention and disaffection," while one of his classmates added that during his stay at the College "the administration was bending over double to appear to be dealing equally with women."

Despite these differences in their Dartmouth experiences and feelings about their classmates, the sample alumni and alumnae seemed to want the same thing - for Dartmouth to do its best for its students, whether by becoming "less conservative" or more vocationally oriented, hiring more women faculty members, decreasing the size of the College, or announcing graduates' names at Commencement. The survey demonstrated what I thought would be true - that the differences and similarities in the first coed classes are among individuals, not between sexes. In the same ways, these graduates are beginning to realize or ignore their "potential for making a significant positive impact on society." Their sex and society's stereotype sex roles do not seem to affect discernably the lives of these men and women, leaving the Trustees with what I see as only one choice short of drafting another statement. That choice is adoption of an admissions policy - one unencumbered with quotas explicit or disguised - allowing men and women equal opportunity to achieve their potential at Dartmouth and after Dartmouth.

'Little babies don't have to pass a sexual ratio test ... so why should there be a ratio at Dartmouth?'

Dartmouth taught her 'to avoid social relationships with spoiled boys who don't want to grow up ...'

A junior from Westfield, New Jersey, A.Kelley Fead follows her father ('44) andbrother ('70) at Dartmouth. She is a newseditor for The Dartmouth and hasdesigned her own major in language andcommunications.

'Coeducationwas a farce ...'

Coeducation was'better thanwalking across theGreen at night ...howling at the moon.'

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

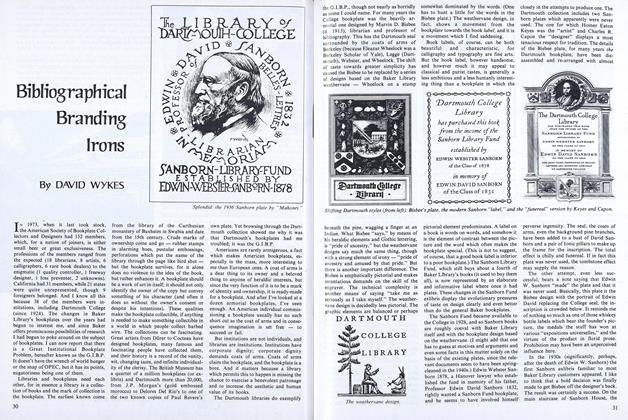

FeatureBibliographical Branding Irons

November 1976 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

FeatureThe and the

November 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

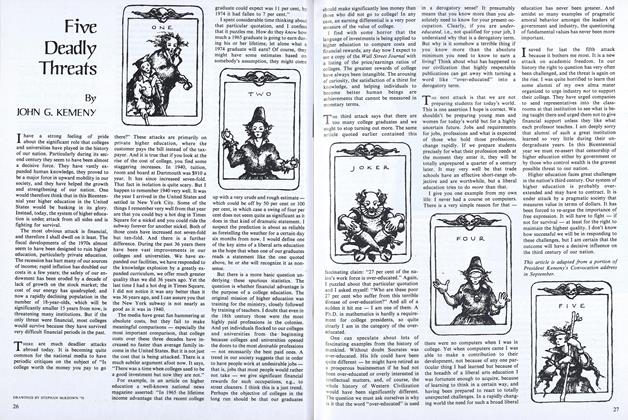

FeatureFive Deadly Threats

November 1976 By John G. Kemeny -

Article

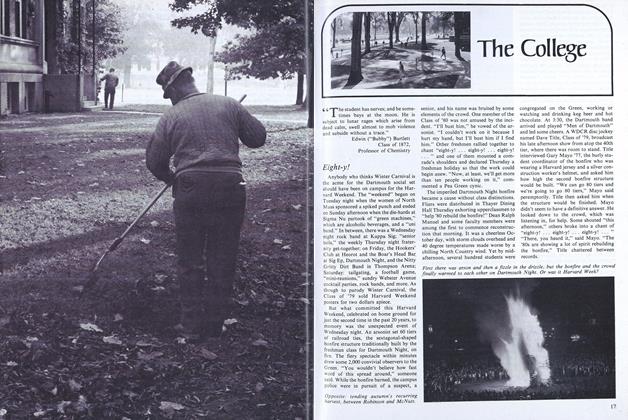

ArticleEight-y!

November 1976 -

Article

ArticleAlan versus Them 'It would be boring otherwise'

November 1976 By PIERRE KIRCH'78 -

Article

ArticleEleazar, Dan and Liz

November 1976 By ELIZABETH CRONIN '77

Features

-

Feature

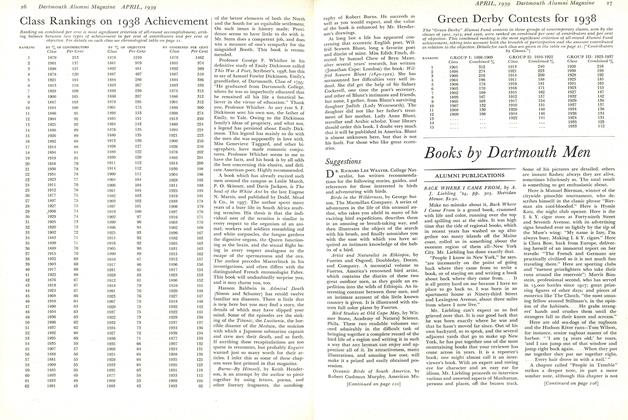

FeatureGreen Derby Contests for 1938

April 1939 -

Feature

FeatureROBERTA STEWART

Nov - Dec -

Feature

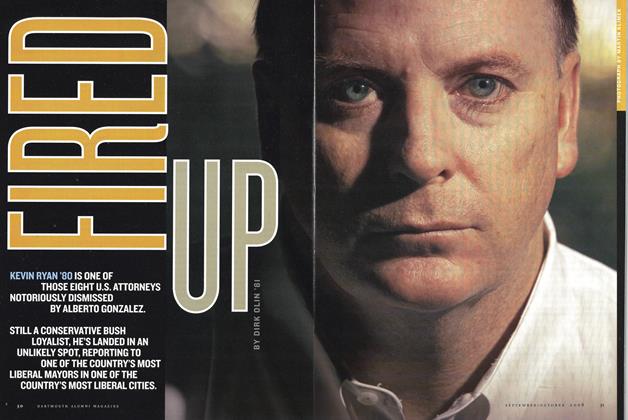

FeatureFired Up

Sept/Oct 2008 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeaturePublic Interest an The Technological Revolution

February 1955 By LLOYD V. BERKNER -

Feature

FeatureWILL TO RESIST

APRIL 1969 By RICHARD W. MORIN '24 -

Feature

FeatureNon-Violent Change in Our Society

JULY 1968 By THE HON. JACOB K. JAVITS, LL.D. '68