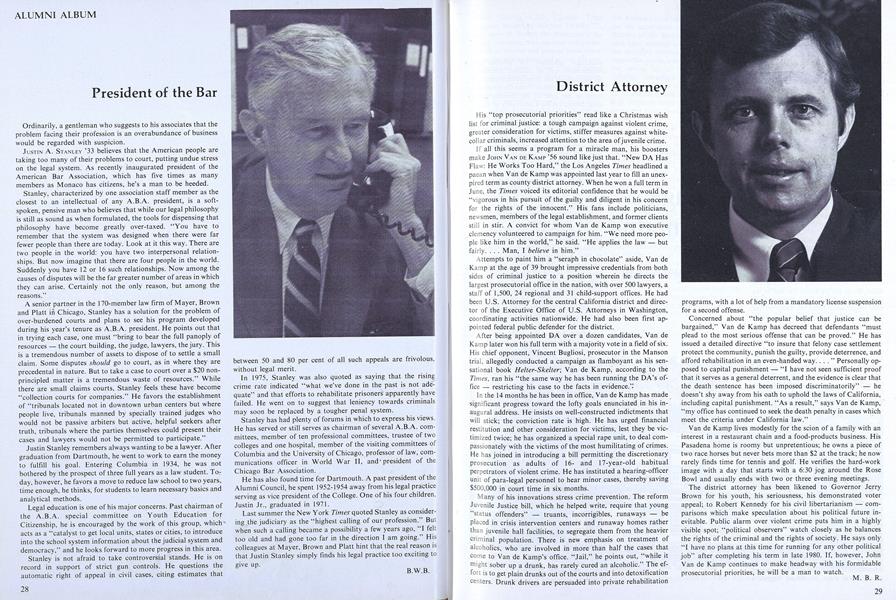

His "top prosecutorial priorities" read like a Christmas wish list for criminal justice: a tough campaign against violent crime, greater consideration for victims, stiffer measures against white- collar criminals, increased attention to the area of juvenile crime.

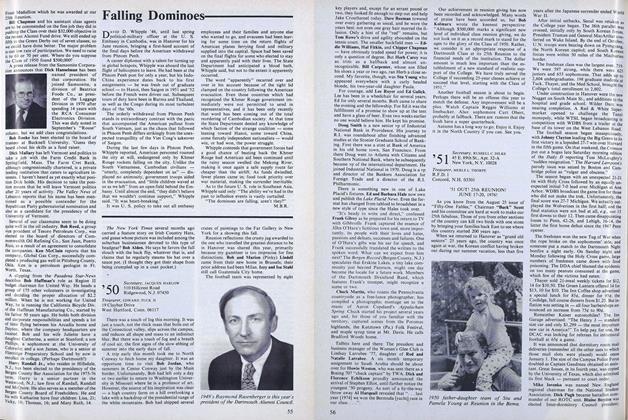

If all this seems a program for a miracle man, his boosters make JOHN VAN DE KAMP '56 sound like just that. "New DA Has Flaw: He Works Too Hard," the Los Angeles Times headlined a paean when Van de Kamp was appointed last year to fill an unexpired term as county district attorney. When he won a full term in June, the Times voiced its editorial confidence that he would be "vigorous in his pursuit of the guilty and diligent in his concern for the rights of the innocent." His fans include politicians, newsmen, members of the legal establishment, and former clients still in stir. A convict for whom Van de Kamp won executive clemency volunteered to campaign for him. "We need more people like him in the world," he said. "He applies the law - but fairly. . . . Man, I believe in him."

Attempts to paint him a "seraph in chocolate" aside, Van de Kamp at the age of 39 brought impressive credentials from both sides of criminal justice to a position wherein he directs the largest prosecutorial office in the nation, with over 500 lawyers, a staff of 1,500, 24 regional and 31 child-support offices. He had been U.S. Attorney for the central California district and director of the Executive Office of U.S. Attorneys in Washington, coordinating activities nationwide. He had also been first appointed federal public defender for the district.

After being appointed DA over a dozen candidates, Van de Kamp later won his full term with a majority vote in a field of six. His chief opponent, Vincent Bugliosi, prosecutor in the Manson trial, allegedly conducted a campaign as flamboyant as his sensational book Helter-Skelter, Van de Kamp, according to the Times, ran his "the same way he has been running the DA's office - restricting his case to the facts in evidence."

In the 14 months he has been in office, Van de Kamp has made significant progress toward the lofty goals enunciated in his inaugural address. He' insists on well-constructed indictments that will stick; the conviction rate is high. He has urged financial restitution and other consideration for victims, lest they be victimized twice; he has organized a special rape unit, to deal com- passionately with the victims of the most humilitating of crimes. He has joined in introducing a bill permitting the discretionary prosecution as adults of 16- and 17-year-old habitual perpetrators of violent crime. He has instituted a hearing-officer unit of para-legal personnel to hear minor cases, thereby saving $500,000 in court time in six months.

Many of his innovations stress crime prevention. The reform Juvenile Justice bill, which he helped write, require that young "status offenders" - truants, incorrigibles, runaways - be placed in crisis intervention centers and runaway homes rather than juvenile hall facilities, to segregate them from the heavier criminal population. There is new emphasis on treatment of alcoholics, who are involved in more than half the cases that come to Van de Kamp's office. "Jail," he points out, "while it night sober up a drunk, has rarely cured an alcoholic." The effort is to get plain drunks out of the courts and into detoxification centers. Drunk drivers are persuaded into private rehabilitation programs, with a lot of help from a mandatory license suspension for a second offense.

Concerned about "the popular belief that justice can be bargained," Van de Kamp has decreed that defendants "must plead to the most serious offense that can be proved." He has issued a detailed directive "to insure that felony case settlement protect the community, punish the guilty, provide deterrence, and afford rehabilitation in an even-handed way...." Personally opposed to capital punishment - "I have not seen sufficient proof that it serves as a general deterrent, and the evidence is clear that the death sentence has been imposed discriminatorily" - he doesn't shy away from his oath to uphold the laws of California, including capital punishment. "As a result," says Van de Kamp, "my office has continued to seek the death penalty in cases which meet the criteria under California law."

Van de Kamp lives modestly for the scion of a family with an interest in a restaurant chain and a food-products business. His Pasadena home is roomy but unpretentious; he owns a piece of two race horses but never bets more than $2 at the track; he now rarely finds time for tennis and golf. He verifies the hard-work image with a day that starts with a 6:30 jog around the Rose Bowl and usually ends with two or three evening meetings.

The district attorney has been likened to Governor Jerry Brown for his youth, his seriousness, his demonstrated voter appeal; to Robert Kennedy for his civil libertarianism - comparisons which make speculation about his political future inevitable. Public alarm over violent crime puts him in a highly visible spot; "political observers" watch closely as he balances the rights of the criminal and the rights of society. He says only "I have no plans at this time for running for any other political job" after completing his term in late 1980. If, however, John Van de Kamp continues to make headway with his formidable prosecutorial priorities, he will be a man to watch.

M.B.R.

-

Feature

FeaturePort Professional

October 1973 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleOf Ancient Mariners... and Monsters of the Deep

September 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleFalling Dominoes

October 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

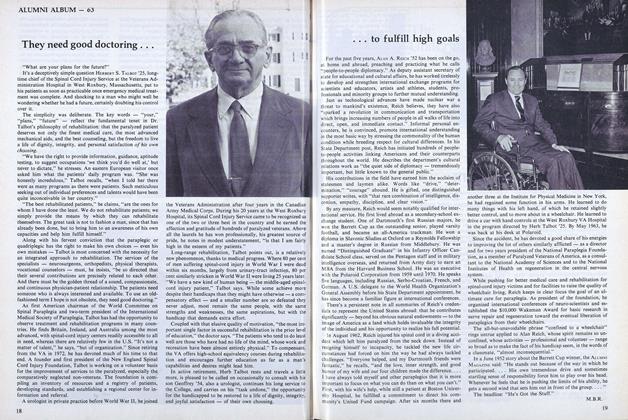

Article... to fulfill high goals

January 1976 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleEqual Opportunity: efforts to make it more equal

June 1976 By M.B.R. -

Article

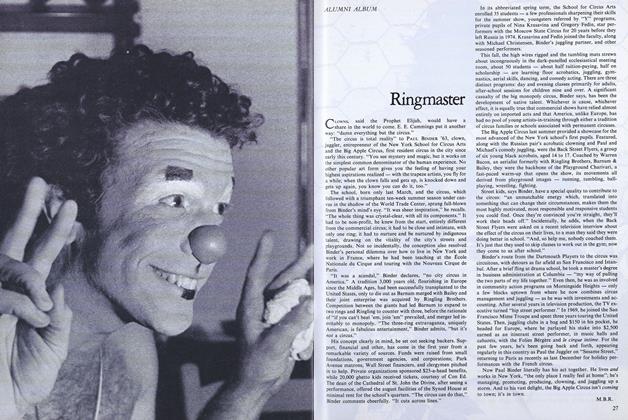

ArticleRingmaster

DEC. 1977 By M.B.R.