A simple mental technique... A simple mental tech... A simple mental... A simple...

February 1977 PIERRE KIRCHA simple mental technique... A simple mental tech... A simple mental... A simple... PIERRE KIRCH February 1977

NOT long ago, I was sitting in a comfortably furnished little room in College Hall with two other non- meditators and a woman, who asked: "Have any of you ever heard anything about Transcendental Meditation?" We all had, of course; but then who hasn't heard of mantras and the Maharishi? The woman, a teacher of Transcendental Meditation, was beginning a free introductory discourse on TM. Two years ago, there were a lot more students present at these free introductory lectures, which were then held in a large meeting room with chairs rather than a small College Hall lounge with some couches and a refrigerator. TM two years ago was the greatest renewal movement going, and it promised to renew not only your weary body but your entire life. "It's not a philosophy, not a religion," meditators insisted, "it's a technique." "Go," said the Maharishi, "and tell the world no one has to suffer any more." Thirty thousand and then 40,000 converts each month were buying a personally assigned mantra, a lifetime guarantee of guidance in the mantra's proper use, and a cornucopia of promises: better grades; more alertness; lower metabolic and blood levels; decreased alcohol, cigarette, drug, and ox- ygen consumption; the elimination of pain; a peaceful society. Time magazine put a likeness of the Maharishi on a psychedelic cover and certified the fad: "The TM Craze: Forty Minutes to Bliss." The Maharishi said it worked. Adam Smith said it worked. Two best-selling books said it worked. It worked!

That was in 1975, a year in which the Maharishi was so sanguine about TM that he proclaimed the coming of the "Age of Enlightenment." But just as TM dawned brilliant into the public consciousness, it shortly after faded out of the public consciousness. Today, the number of new initiates is back at about 10,000 monthly — the number of beginners before the media hullabaloo. What has happened to the TM movement? "The overall statistics of people beginning month to month depends on the publicity given TM," says Charlie Donahue '66, a polished talker who has been meditating 40 minutes daily for the past decade, has taught TM for the past seven years, and who works in Cambridge, Massachusetts, as the East Coast coordinator of the International Meditation Society. "A lot of people get into it because it is a fad at the time. I prefer people who think it out carefully, who give it a lot of time before being initiated."

But if Transcendental Meditation is no longer a fad with the media or with students at colleges like Dartmouth, that does not mean that the movement is nearing its end. Quite the opposite. The TM movement is now flourishing as an established part of the Establishment. There are 7,000 TM teachers in the United States, working out of more than 350 TM organizational centers. The World Plan Executive Council — U.S., the non-profit, tax-exempt, educational TM organization in this country, does millions of dollars worth of business under the rubrics of the International Meditation Society, the American Foundation for the Science of Creative Intelligence, and the Spiritual Regeneration Movement. There is a Maharishi International University in lowa and a Maharishi European Research University in Switzerland. At Dartmouth, the chapter of the Students International Meditation Society is an official student organization, and the College allocates money for its activities. The movement owns academies and country retreats, produces color videotape lessons, and publishes glossy promotional booklets (sample titles: "Fundamentals of Progress," "Excellence in Action"), and books (latest title: Scientific Research onthe Transcendental Meditation Program:Collected Papers).

The other consciousness-raising or self- improvement or human potential movements — Arica, est, the Divine Light Sect, Silva Mind Control, Esalen, Gestalt, Rebirthing, Rolfing, and the others — are ephemeral diversions for far-out, "radical chic," adventuresome members of the upper middle class. They're not for everybody. "You see a lot of techniques like TM," TM's Donahue says, "but they get soaked out." The popularity of TM varies. In the late sixties, the Beatles made Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, scientist and Hindu monk, a media star, and he appeared on the late-night talk shows, a squeaky-voiced, giggly complement to the Charos and the Capotes. And then TM faded out of the public's consciousness for a few years. Eighteen months ago, two years ago, it was trendy; today it isn't. Says Donahue, "Those crests of the wave that occur periodically are sort of artificial. They are not a true reflection of the response to TM in this country."

THE movement was destined to become a part of the Establishment because that is what it consciously or unconsciously endeavored to do. "A lot of people, when they think about TM, they think about the Far East and people wearing beads," the TM teacher said in College Hall. "But really, it is just a simple mental technique." A simple mental technique, TM people repeat, mantra-like, over and over again. Anybody can do it. TM is for everybody. Two TM teachers wrote a playful book about TM entitled The TMBook, a bestseller two years ago, which assured non-meditators interested in meditation that to practice TM you don't have to be a vegetarian ("I can still eat Big Macs? You can eat anything you want."), an eater of brown rice, or a wearer of funny clothes or sandals. Normality. No encounter sessions, no crawling on the floor, no Rolfing. The TM movement does not offend middle-of-the-road, middle-class sensibilities. At the end of 1976, the movement sponsored a "Winter Festival of the Age of Enlightenment" in more than 1,000 cities world-wide, and presented Chamber of Commerce-like awards to outstanding community citizens. Public Relations. The movement is big on reprinting testimonials, magazine and newspaper articles ("TM May Make You a Winner," "Transcendental Meditation and Its Potential Uses for Schools"), congressional hearings, effusive letters from important people. The magazine and newspaper reprints do not come from Rolling Stone or High Times but from PhiDelta Kappan, The Wall Street Journal,Social Education, the Boston EveningGlobe. Testimonial letters have come from a vice presidentof the Philadelphia Phillies baseball team, a Jesuit priest at the University of Sudbury in Canada ("It requires no faith. ... It is not a religion but atechnique"), the founder and chairman of the board emeritus of the Ampex Corporation in California. The Establishment. For athletes, the movement publishes a special booklet that promises TM will cultivate "deep rest for dynamic action ... improved concentration ... faster running speed ... increased endurance ... increased stability ... improved reaction time ... improved interpersonal relationships."

I saw a group photograph of the Maharishi with a graduating class of TM teachers, all wearing suits or dresses or pantsuits or skirts, and there were all the well-scrubbed, glowing faces and toothy smiles that I remember from my yearbook portraits. TM teachers are neat, clean, and respectable. When college students were wearing their hair fashionably long, many of the TM teachers wore their hair conservatively short. The free introductory lectures are not meant to pressure curious people into buying the program; you can accept or reject what the teachers say. But if you accept, and want to learn more, you must pay in full — no installment plans or credit extended — before they will teach you a personally assigned mantra. Abusiness deal. There are two other commitments you must make in order to consummate the deal: a commitment of time and a commitment to abstain from what the TM teacher in College Hall labeled "recreational" drugs — drugs other than coffee, alcohol, cigarettes, colas, and prescription drugs; in short, those drugs that are illegal — for the 15 days before the mantra is taught. "This is not moral but physiological," the teacher assured a 20 year-old-college student. It is' not areligion, not a philosophy, but a technique.

Every aspect of the TM program is inoffensively, wholesomely American, and it is not surprising that some 900,000 people in this country have invested in mantras and the Maharishi and taken the Transcendental Meditation course. But even that figure is. a poor representation of the acceptability of TM to the general public. Last November, George Gallup reported that four per cent of a population sample, a projected six million Americans, said that they "practiced" or were "involved in" TM. Did the more than five million meditators who didn't take the official Transcendental Meditation course learn the technique from friends who had taken the course, something TM teachers say not to do? (The teacher in College Hall: "You need a teacher to make sure the sound [mantra] is . . . suitable to the nervous system, and for the technique — how to use the sound properly. The teacher is a guide to make sure everything goes right along the way. The teacher must do this to ensure the purity of the teaching. Once the knowledge is distorted in any way, the technique is gone.") Did they follow the thrifty advice of Herbert Benson, a non-meditating Harvard cardiologist and TM apostate of sorts, and practice the "relaxation response": to sit quietly, relax the muscles from toes to head, and mentally repeat the word "one"? (The teacher in College Hall: "The effect of 'one' on the nervous system is not a beneficial effect to some people.")

Before the media ballyhooed "The TM Craze," three fourths or more of this country's meditators were students. Now, TM's Donahue confirms, older people, working people, are learning the technique in large numbers. One Dartmouth student told me she was persuaded to attend an introductory lecture by her parents, both doctors, both meditators. Attending introductory lectures these days are not only skeptical students ("I'm still not convinced that it's not some kind of positive reinforcement to saying, 'l'm going to take some time every day just for myself' ") but also middle- aged, middle-class mothers who have extra dollars to spend, bring their daughters with them, and say things like "A friend of mine read about a movie actress who was able to sleep less after she began to meditate — is that true?" and ask "Does it help with things like smoking?"

TM is an accepted 22-minute respite from activity, a cultural phenomenon like the 15-minute morning coffee break. I telephoned the home of a meditator who was off-campus during the fall term, and his mother answered the phone and said, "He comes home at 4:30 and usually meditates shortly after." I had not mentioned TM and she said that to me — a stranger! — with the same matter-of- factness that she might have said he comes home at 4:30 and sits down to dinner. TM teachers ask initiates to bring with them six to 12. flowers (the flowers of life), several pieces of sweet fruit (the seed of life), and a white handkerchief (cleansing of the spirit) to the ceremony at which an initiate is personally assigned a mantra; when I asked the sales clerk in Robert's Flowers on Main Street for "eight of the cheapest flowers you have," she had heard the query before: "Is this for meditation?" she asked.

I ATTENDED two introductory lectures in College Hall, and then I took the course in late November. There are seven steps to learning the Transcendental Meditation technique: two introductory lectures, a personal interview with the teacher, personal instruction in the use of the mantra, and three consecutive group sessions of "checking" the technique and sharing meditation experiences.

My teacher was a woman named Cindy, who is 28 years old, started meditating while a student at the University of Vermont because "there was mental tension in my life and I wanted to get rid of it," and says that meditation has made her more emotionally stable and has developed for her "the very broad comprehension to see a situation for what it is." Cindy told me she met the Maharishi on a one-to-one basis in a hotel ballroom in Murren, Switzerland, after spending half a year studying videotapes of the Maharishi teaching how to teach TM. Before the Maharishi certified Cindy as a teacher, he passed on to her his interpretation of the Vedic tradition, a 6,000-year-old oral tradition that the Maharishi 30 years ago learned in Northern India from his teacher, a man named Swami Brahmananda Saraswati — known posthumously among meditators by the less laborious appellation of "Guru Dev." Guru Dev taught the Maharishi the mantras, meaningless Sanskrit sounds that have been handed down orally and seem to be euphonious and pleasing to the mind, and a system of rules by which to determine which mantra will go to an individual with a particular nervous system, and that knowledge the Maharishi personally passes on to the teachers. Cindy, before she moved to southern Vermont, taught the technique at the Upper Valley TM Center, which is located in a house three blocks from campus. There are about 800 meditators in the Upper Valley area, three or four per cent of the population, including about 300 people who are members of the Students International Meditation Society at the College.

Introductory lectures were given in Hanover on almost a weekly basis during the fall term. They were usually held in College Hall, but some were held at the town library, several blocks from the corner of Main and Wheelock streets. "When you talk to a businessman or housewife, their interests are different as far as the benefits they want to get from the technique are concerned," Cindy told me. The introductory lectures were publicized around campus with color posters announcing, "Transcendental Meditation is ... dynamic action from deep rest" and "Rest is the basis of activity. ... Deep rest is the basis of clear thinking and effective action .... For deeper rest and more dynamic activity, Transcendental Meditation."

My classmates in this endeavor were a freshman who in high school knew somebody who meditated, a graduate student who at the first lecture volunteered, "I have some idea about the physiological aspects of TM because I am a physiologist," and another freshman who joined the group for the three "checking" sessions.

The introductory lectures made the same points that are repeated over and over in the TM literature: the personal and social benefits of meditation, why it works, tension, potential, happiness — TM is nota religion, not a philosophy, but a simplemental technique. Is there a reward when you first meditate that will make you want to do it again? someone asked. "Everyone," Cindy the teacher said, "receives the benefits of meditation at different times. Some people receive the benefits right away, some people notice results after a few months. It depends on your nervous system." What about this mantra — what happens if you tell someone else the mantra? "If you spoke the mantra out, it could weaken your meditation. To speak it out is to make an abstract thought concrete." What would happen if you went to two different teachers — would you receive two different mantras? "Maharishi gave me specific instructions for giving mantras. I don't know what he told the person before me or behind me. It's not something teachers ever discuss. . . . There is no possibility I can give the wrong mantra." How does TM differ from religions that repeat a mantra — the Zen Buddhists — or is it different? "TM is just a technique. . . . Anything like Zen, where you repeat over and over, the purpose of that is control of the mind. TM is not control of the mind; the necessity to repeat in TM simply allows the mind to go inward." And so the introductory lectures went.

The physiologist after the first lecture: "I more or less came to the conclusion that I don't believe it . . . but I am willing to give it a try." "Sometimes," Cindy said, "skeptics are easier to teach because they don't expect anything to happen." The freshman who in high school knew somebody who meditated: "I'm going to try it, I think it works. But some of the obscure terms they use, when they read what the Maharishi says, I feel like it's a snow job — terms like 'fulfillment of consciousness.' "

The personal interview, which the teacher uses to find out about a person's nervous system so that a mantra can be assigned, consisted of filling out a form headed Jai Guru Dev and answering several questions. My teacher and I were in a room that had a photograph of the Maharishi on each of four walls. The form asked whether I had ever taken hallucinogenic drugs or any other drugs, whether I had ever been under psychiatric care, how well I was sleeping, the state of my physical condition, and other questions. At the bottom of the form I signed a statement that said the TM instruction was for my own personal use and that I would not disclose to anyone my personally assigned mantra or how to use it and that I would not publish, instruct, or impart to anyone the TM technique until Maharishi Mahesh Yogi had personally trained me and said it would be all right to do so. "As a teacher," Cindy said, "I must know that you will do this before I can teach you. I have a responsibility to uphold the purity of the teaching." I agreed. Write about the benefits of meditation, she said, but not your experiences during medita- tion. "If you were going to go and write and say that something happened to you when you meditated, someone who read that would assume that the same would happen to him. But the experiences of peo- ple are different because their nervous systems are different."

About ten days later, when it came time to learn my mantra and how to use it, Cindy led me into a room that had candles and incense burning, a makeshift altar on which my flowers, sweet fruit, and white handkerchief rested, and a color portrait of Guru Dev, the Maharishi's teacher. We stood there without any shoes on and my teacher asked me if I agreed that my mantra would be kept a secret and I agreed and then she asked me if I agreed that the teaching would be kept a secret and I agreed. Cindy then knelt down before the makeshift altar and the color portrait of Guru Dev and began to recite a song in Sanskrit.

During the final week of the fall term, I experimented and "pulled" two all- nighters on TM rather than No-Doz — and it worked. (Interpretation, scientifically validated: reduced use of non- prescribed drugs, faster recovery from sleep deprivation.) The physiologist told me that she tried substituting a pleasing sound for her mantra in meditation and that it did not work; recently I tried Adam Smith's mantra, which like mine has two syllables, and my mind kept drifting from his mantra back to my own well-practiced mantra. Why does the personally assigned mantra work? TM teachers try to convince the rank-and-file meditators that how mantras are assigned is not their concern. They will tell you there is a scientific, systematic way, taught to TM teachers by the Maharishi, in which they are assigned; and that is all they will reveal. "We don't burden our students with extraneous concerns. To give out an explanation of one aspect of TM would be a disservice," a Dartmouth alumnus who teaches TM once said. My TM teacher wouldn't reveal in the introductory lectures how many different mantras there are; when later I asked her if the figure 17, which Time attributed to a "knowledgeable source," were accurate, she said that it was and that the Maharishi himself had said so on the Merv Griffin Show anyway.

Meditators can have more than rank- and-file knowledge. But to gain more knowledge, meditators must give more time or more time and money to the movement. There are advanced lectures (free, every Sunday night in Hanover); checking — the "tune up" of meditation — and checker training; weekend residence courses at country retreats (cost: about what you would pay to stay in a Holiday Inn for two nights); a 33-lesson course in the Science of Creative Intelligence, the theoretical understanding behind the Transcendental Meditation program, which counts for academic credit from Maharishi International University (cost: $150 for meditating adults, $125 for meditating college students); teacher training (three phases: two three-month periods of in-residence instruction and three months of field work; total cost, including air fare to Europe: $3,800); advanced teacher training; and more.

At the pinnacle of the TM empire is the Maharishi, whose name translates as "Great Seer." His image is ubiquitous in TM books, pamphlets, on posters, on the walls of the Upper Valley Meditation Center and the SI MS-Dartmouth office: the white silk dhoti; the bronzed, seraphic visage; the mane of gray-flecked hair; the flowing white beard; the enigmatic facial expression — mystical, meditative, Far East. One TM pamphlet promoting an "Ideal Society for the Granite State" refers to the Maharishi as "His Holiness." During an introductory lecture, Cindy, the TM teacher, started to talk about the ceremony before the portrait of Guru Dev, the Maharishi's preceptor, and the makeshift altar with the burning candles and incense. The freshman who in high school knew someone who meditated said, "This is starting to sound slightly religious." "There is nothing religious in the ceremony," Cindy rejoined. "It is a ceremony recited in Sanskrit saying 'thank you' to those who had the knowledge before you. The only purpose of the ceremony is to prepare the teacher to teach. It's no different than when a judge comes into a courtroom; he wears robes and something is recited in a foreign language, in Latin, to prepare him for his role of judge." It is not a religion, not aphilosophy, but a technique. "I believe in the benefits, but not the organization . . . like the ceremony, the incense burning, that bull," the freshman told me after the course. I was talking to Cindy once about the lifestyle of TM teachers and she said "Maharishi" — Cindy, like a lot of people who take TM very seriously, drops the article before the Maharishi's name — "wants me to be comfortable," and it was then that I asked her whether the constant references to the Maharishi, all the pictures of him, doesn't that constitute godlike veneration of the Maharishi? She said it doesn't. "I have a tremendous amount of respect for the man," she said. "He is warm, friendly, open — that sort of respect I have."

COLLEGE students, attracted to TM for what one TM teacher calls its "academic and spiritual value," gave the movement its impetus a decade ago. Until 1974, about 75 per cent of new meditators came from college and university campuses. In late 1965, the movement was unpublicized and unknown, and there were as few as 200 people in this country who had learned the technique from teachers of the Students International Meditation Society. The Maharishi in late 1966 accepted a Yale student's invitation to speak in New Haven; within two months after his talk before a capacity audience, 120 members of the Yale community learned the technique. Six years later there were more than 1,000 meditators at Yale. Dartmouth's SIMS chapter was founded in 1969, and by 1970 chapters had been started at all of the Ivy League colleges and most of the Eastern colleges.

College campuses are well-known as marketplaces for the arcane and the abstruse, and it is not surprising that TM has become as habitual as brushing teeth for many students. Meditation is well suited to student life; it is 22 minutes of morning calm and 22 minutes of late afternoon calm in the midst of the fury. "It prevents me from getting burned out in a day," Scott Latimer '77, who is captain of the fencing team, told me. "I tend to schedule myself into so many things that I am up against a wall — for me, that's a way of going fast because I have two rest periods in the day, not just physical rest periods, but mental, too." "Nothing can beat it during exams," says a member of the Class of 1975. Students will meditate anywhere there is a place to sit down: in Baker Library — in the stacks, in the microfilm room; in the SIMS office in Robinson Hall; in the bleachers in Alumni Gymnasium; in dormitory rooms. There is a group of meditators who do their 22 minutes together in Robinson Hall at 5:30 on weekday evenings.

There are many movements that not only begin on college campuses but end there, too. Why in the last several years has TM also appealed to the general public, the non-college educated, the working people? The probable reason TM "soaked out," to use Charlie Donahue's term, the counterfeits and competitors is that TM fits in snugly with middle-class values and expectations, the middle-class way of life. Establishment. Respectability. Anybody can learn it, TM people say. It's natural. Virtually a zero per cent failure rate.

The beginning of an introductory lecture in the Hanover town library to an audience composed of a woman and her two daughters: "TM seems to be a timely solution. People have many material comforts, yet there seems to be something missing .... Inner development is not flourishing with this outer development. People feel there is a gap between what they want to achieve and what they are accomplishing. Psychologists tell us we're not using our full potential, that we use only five to ten per cent. That's hardly anything!" People feel tired, people feel run down, and TM is a palliative without class distinctions. What adult cannot afford to pay the TM fee of $125 or the price of Herbert Benson's book in exchange for happiness? There is cause for six million people in this country to claim they "practice" or are "involved in" Transcendental Meditation. The movement publishes a chronicle of 64 physiological, psychological, sociological, and ecological benefits from TM. TM promises to pick you up so that you will love life, as though to say: You can be your own best friend, you can be awake and alive, you can find freedom in an unfree world. The seraph-faced "Great Seer," the Maharishi, promises all the things a candidate for president might promise: abundant love and happiness, an end to suffering and war ("because the Science of Creative Intelligence makes the minds of men more orderly, it eliminates the basis of war").

The best thing about TM is that youdon't have to try. Introductory lecture in the Hanover town library: "To learn how to meditate is so easy — all you need is a thought." Can Zen Meditation, est, Rebirthing, or Rolfing promise as much? Improved job performance and satisfaction, increased normality, reduced use of alcohol and cigarettes, relief from insomnia ... but most of all the dissolution of stress, of tension . . . and you don't have to try! Anybody can learn it. ("Not even literacy is required or assumed for an individual to be successfully instructed" — TM publication.) It's natural. Virtually azero per cent failure rate. The solution toall problems! The Age of Enlightenment, the Maharishi avows, will be a time when "life will not be a struggle."

Yet some teachers claim that this array of promises is no longer what lures most of the people to the TM introductory lectures, that beginning meditators today are not drawn by publicity but by friends who meditate. Charlie Donahue says that few people — "a class of people, some scientists" — read the literature that promises, and cites sources for scientific proof of, things like 64 physiological, psychological, sociological, ecological benefits. Cindy, the TM teacher, in College Hall: "You know people who have changed after starting to meditate.. . . That works as a sort of verification." Her student, the physiologist: "A medical doctor that I respect suggested I come. But it's very hard to swallow. ... If I didn't know so many people who I respect who meditate, I'd think you're crazy." Scott Herriott '75, who is chairman of the New Haven TM center: "A lot of superficial reasons are given to go into TM, such as relaxation. I myself am not stupid enough to pay $65 just to relax. ... As time goes on, and more people have been meditating three, four, five, maybe ten years, more people will understand the depth of TM. ..."

I wanted last November to learn about TM without learning how to meditate. But after talking with a few meditators I decided to learn how to meditate. What is striking about the movement's disciples, those who look upon TM as more than just a straightforward technique, is that they like to talk about TM, just as hockey players like to talk about hockey and debaters like to talk about debate — they will say things like "he's a very strong meditator." They are sincere when they say that meditation has improved their lives in simple, subtle, yet important ways. I was intrigued by TM, by the self- assurance and sincerity of meditators I talked with, yet still I considered Transcendental Meditation, the whole self- improvement "biz" from Transactional Analysis to Rolfing to Rebirthing, as artificial: TM seemed as passive as watching television. I didn't need increased normality or "help" for "things like smoking." A professor at the College who is a long-distance runner once told me that after a good run he feels relaxed and can sit down in the library and concentrate non- stop on his work for hours. That is the achievement of relaxation, concentration, and good health through will power; you don't buy it and not anybody can do it. Active self-betterment is antithetical to the TM pitch. But then I talked with Scott Herriott, the chairman of the TM center in New Haven. Herriott learned the TM technique in the winter of his freshman year, and two years later he went to Valbella, Switzerland, where he was personally trained and approved to teach TM by the Maharishi. He takes scholarship and meditation very seriously. He is not run down, he is not tired, he is not jaded by academics or life. He graduated with one of the highest grade point averages in his class. Summa cum laude. Phi Beta Kappa. Of Dartmouth, he says: "I loved it." Of his courses: "I had a ball, I enjoyed all of them immensely."

I came to realize for myself after talking with Scott Herriott that TM complements active endeavors — running ten miles or reading a work of literature or engaging in a love affair — in that it enhances the wholeness of man: the spiritual, the mental, the physical. "Psychologists tell uswe're not using our full potential, that weuse only five to ten per cent" — meditation is a support in the quest for excellence in everything . . . the Greek arete. TM wouldn't work, I think, in a passive, sedentary life — that would be heaping boredom upon boredom. It is 44 minutes daily of quiet... of turning inward. Herriott: "TM is something more fundamental than gaining some degree of relaxation. The kind of publicity the TM program has gotten in the past is that it is for relaxation. You read articles in newspapers about relieving stress, and it makes it sound like a person would be a bowl of Jello. What you can write about is the inner stability, you can talk of stability of emotion, integration of personality." It is not a religion, not aphilosophy, but a technique — yet it is more than a simple mental technique, it is a philosophy, a philosophy of life. "TM is so much more," Herriott told me. "It unfolds potential. . . . The longer time goes on in meditating, the less sufficient it is to explain the TM program in terms of only stress. ... You have to explain the TM program in terms of something being enlivened. . . . Something which is much more fundamental to life."

I realized then that the benefits of TM are subjective, just as life is subjective, and that a list of 64 scientifically validated benefits doesn't really mean anything. The Maharishi's proclamations don't mean anything. I'm going to solve my problems; TM won't. What matters in TM is the individual, and when meditators are asked what they get out of TM, they give a lot of different answers, some simple, some sophisticated. The simple: "A lot of times," says Marty Leamon '78, "meditation in the morning makes me feel really happy." The sophisticated: Donald Pease is an English professor at Dartmouth who is writing a book about 19th-century American literature, has meditated during the last seven years, and plans to become a TM teacher. "There is," he told me, "a correlation between TM and what could be called logos — the word of literature." I didn't quite understand what he meant. This is what he said:

I see TM as placing one in perspective so that one can see the entire body of world literature as a totalized whole, instead of seeing discrete units without any relationship to each other. Through TM, I see the interrelationship, I see the living word, that reveals itself in irony, and tragedy, and romance, and comedy. Literary genres are the steps by which to enter into the total revelation of being in the Word [mantra] of meditation — the Word with a capital W, in silence, the basis of all words, with a small w.

All of literature is one story that is at once stated and repeated. Through meditation, you experience the total story. ... There is that interrelationship between literary works that would be otherwise discontinuous. Once the experience of literature is living, then the words become alive as if they were a living aspect of being. Words become friends, they become things you want to know, to experience in all their resonances. Language begins to resonate, to have totality. . . . I'm not saying that only meditation allows you to experience that. A lot of people see in literature the logos who do not practice meditation.

CONVERSATION in Thayer Dining Hall: "I don't think it was worth it," said a freshman who one month earlier had learned to meditate. "I think it relaxes me when I'm actually doing it, but other than that, I don't see any day-to-day benefits from it. If I had known more about TM before putting down my 65 bucks I think I could have taught myself. You don't need the course and you don't need the teacher."

"That's not what a TM teacher would tell you."

"They have a line for everything."

Caveat emptor? Scott Herriott says that it is impossible for a normal person to be unable to meditate. Moreover, the TM movement makes the same guarantee that Ray Kroc makes of the Big Mac: Wherever you go in the world, the product will always be the same. Perhaps the only thing about both Kroc's hamburger and TM instruction that has changed in the last 15 years is the price. When Charlie Donahue learned how to meditate ten years ago, the price was $35 for students and $55 for working adults, and the fee was more of a donation that a "money requirement." When Adam Smith, who invests money and writes books, learned how to meditate, it cost $45 for students and $75 for adults. When I learned how to meditate last November, the price was $65 for students and $125 for adults. The TM movement, of course, could not flourish without a steady flow of income. Is it worth $65? $125? the consumer asks. Can I buy happiness for less — bargain basement mantras — or, better yet, obtain it free? Why not share a mantra? "Why Pay to Meditate?" McCall's, womankind's bellwether of trendiness, queried last year, and went on to describe the Maharishi as "laughing as if on his way to the bank." The result of the consumer's money consciousness is that there are a lot of ways to meditate, all but one of which are very inexpensive, and six million meditators, only a fraction of whom have learned the Transcendental Meditation technique as taught by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

TM people say that nobody is getting rich because of TM earnings. Almost all TM teachers make little more than a poverty-level income from their initiations. Donahue, self-described as "one of the foremost men in the organization" and responsible for 100 TM centers on the East Coast, has a salary of $600 per month. In 1969, he had a Dartmouth A.B., had been the recipient of a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship for graduate study at the University of Chicago, was one of the few full-time TM teachers in this country, and was making $30 per week plus expenses. "I never understand," he says, "why people go on harping on the financial side so much. ... If there is some potentiality to the technique, some efficacy, some reason why it should be taught ... to that end, there must be some structure, some supportive structure." The local TM center sends the initiate's entire fee to the TM headquarters in Los Angeles, which keeps 35 per cent of it, credits 15 per cent of it to the teacher for advanced training credit, and returns the remaining amount to the local center to support both the teacher and the center. Few teachers earn as much as $400 monthly; many make less than $200 per month. Many hold second jobs. Donahue: "If you talk to the teacher in Hanover or any other place in New Hampshire and ask how much money they make, you'd be surprised." Cindy, the TM teacher in Hanover, held a part time job in a Main Street bookshop and said that her salary varied from month to month. "The first priority goes to the running of the center. If initiations are low, my salary is the first thing to be cut. . . . Between the two jobs, I manage to get by."

Ten years ago, five years ago, most of the people going to India or to Europe to learn how to teach TM were college students or recent college graduates. Today, as with the TM clientele, the 7,000 teachers of the technique in the United States compose a more heterogeneous group. Meditating lawyers, doctors, businessmen, professional photographers, college professors, and other professionals are investing months of time and about $3,800 to learn how to teach people to meditate. Establishment. Many of the college students who become teachers do so in pursuit of the Better World, just as students in the sixties joined the Peace Corps and took over administration buildings in pursuit of the Better World. But TM is non-violent and non-political (itis not a philosophy, not a religion ... ). The TM teachers I know have got a lot of time and money invested in the movement and won't do anything thai they think might hurt the movement in even the most insignificant way. Scott Herriott sent me a list of 18 Dartmouth alumni and one Dartmouth undergraduate whom he has "heard of" being TM teachers. The list includes medical school students, and graduate students in architecture, physics, divinity, physiology, and Chinese at various universities including Harvard and Yale, Some are teaching the technique in cities as disparate as Waukesha, Wisconsin, and Philadelphia. The last time I talked with Herriott he was preparing to leave for an advanced TM course in Europe. In several years he plans to enroll in the Stanford School of Education and afterward become a college administrator.

Gary Beane '76, who is taking five years to complete his Dartmouth requirements, is the undergraduate TM teacher. He once spent six months studying in southern Thailand and last year he spent six months in Avoriaz, France, where he became the 10,801 st teacher world-wide to be personally instructed and approved by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Last fall, he was in Laconia, a city of 16,000 people in the lakes region of New Hampshire, investigating ways TM could help to alleviate civic problems under an internship sponsored by the College's Public Affairs Center. Beane is the president of the Dartmouth chapter of the Students International Meditation Society, which has a newsletter for the 300 known Dartmouth meditators, an annual activities allocation of approximately $500 from the College, an intramural volleyball team, and an office in Robinson Hall. The TM office, which is mostly used as a meditating room, has a few frayed armchairs and a couch, and a heater that smothers the small room in narcotic warmth.

Gary Beane plans to make education and TM his career. He wants to take the Age of Enlightenment Governor Training Course at the Maharishi European Research University in Weggis, Lake Lucerne, Switzerland, and would like to apply the course in partial credit for a graduate degree in Vedic Studies from the Maharishi International University in Fairfield, lowa. He wants afterward to teach TM to government workers and businessmen in a program under the American Foundation for the Science of Creative Intelligence. He is also interested in teaching a curriculum program on SCI under the International Foundation for the Advancement of Education. "I consider this a career," he says.

NINE hundred thousand people in this country have taken the official Transcendental Meditation course in the hope of attaining some personal benefit. But there is more to the movement than enabling individuals to reduce tension or blood levels, become more normal, gain relief from insomnia, and the 60 other publicized benefits. The ultimate goal of the movement is to change the world in what would seem to non-meditators as fantastic ways. TM is probably the first movement known to man that advocates personal inaction, 44 minutes of inaction daily, as the solution to all the world's problems. Charlie Donahue: "TM has an efficacy beyond a political movement. ... We believe we will have a useful influence .... I do believe that if a lot of people meditate we will have a different sociological and psychological framework in which to work."

Two months ago, "The Winter Festival of the Age of Enlightenment"; six months ago, "The Month To Create an Ideal Society"; two years ago, the coming of "the Age of Enlightenment"; five years ago, the inauguration by the Maharishi of the World Plan. The World Plan is the most important of these declarations and proposes the construction of 3,600 World Plan centers (each to contain, among other things, a soundproof meditation hall with 108 comfortable chairs for meditation, an SCI prep school, eight fountains, a lot of flowers, and eight waterfalls) for the earth's 3,600 million inhabitants. There is to be one SCI teacher at the centers worldwide for each 1,000 people, and Global Television — with transmitters developed by the Veda Vision branch of the Maharishi International University Research Division — will, according to a TM publication entitled "Alliance for Knowledge," "set the world's atmosphere reverberating in the impulses of creative intelligence" and "bring the Science of Creative Intelligence into every home."

Will an abundance of World Plan Centers with flowers and waterfalls and teachers of SCI solve all the world's problems as the movement claims? One thing is certain: The movement continues to advance slowly upon its goals. Gary Beane told me that over 600 cities in the United States and the states of Vermont and Alaska have populations of which at least one per cent of the people practice the TM technique. The Maharishi claims that when one per cent of a community is meditating, the negative trends of society become positive trends, and that when five per cent of a community is meditating, you have an Ideal Society. As far as physiological, psychological, sociological, and ecological benefits are concerned, they too are on the increase. Five years ago, a TM publication listed 48 of these benefits. The publication TM teachers today are handing out at the introductory lectures lists 64.

"Lumiere," lithograph by Odilon Redon, 1893. Dartmouth College collection.

Pierre Kirch '78 is one of this year's undergraduate editors. He comes fromCalifornia.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNever Let Go

February 1977 -

Feature

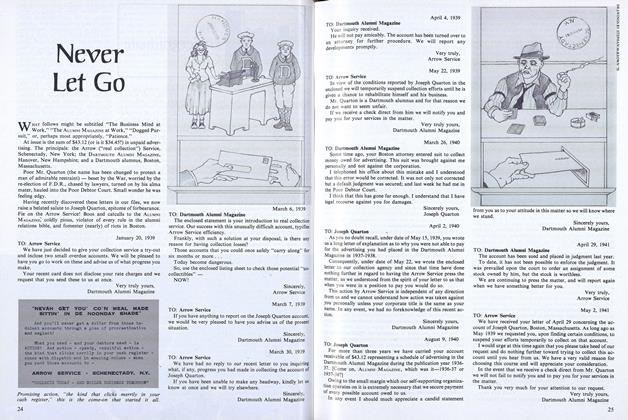

FeatureTwelve legs, six imaginations, one soul Pilobolus

February 1977 By PHILIP HOLLAND -

Feature

FeatureComposite Artist

February 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleStepping Out with a Bounder

February 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

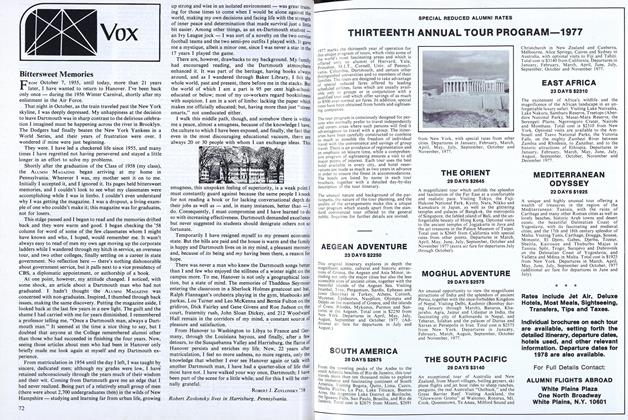

ArticleGray Is Beautiful

February 1977 By ELIZABETH CRONIN '77 -

Article

ArticleBittersweet Memories

February 1977 By ROBERT J. ZOVLONSKY '58

PIERRE KIRCH

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTHIRTEEN IS LUCKY

October 1954 -

Feature

FeatureRefugees' Friend

MAY 1967 -

Feature

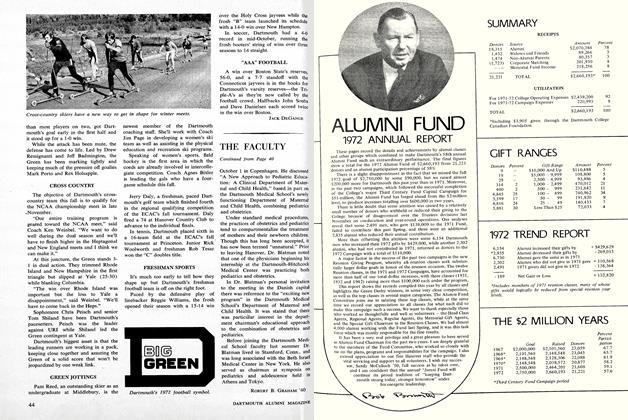

Feature1972 ANNUAL REPORT

NOVEMBER 1972 -

Feature

FeatureAbout Students

April 1975 -

Feature

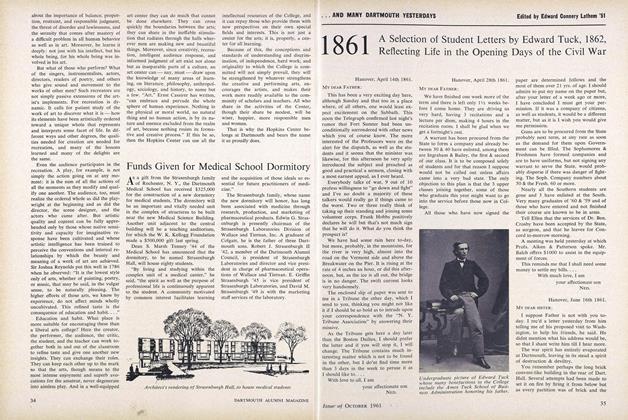

Feature... AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

October 1961 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's "New" Curriculum

APRIL 1966 By JOHN HURD '21, PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH EMERITUS