FROM October 7, 1955, until today, more than 21 years later, I have wanted to return to Hanover. I've been back only once — during the 1956 Winter Carnival, shortly after my enlistment in the Air Force.

That night in October, as the train traveled past the New York skyline, I was deeply depressed. My unhappiness at the decision to leave Dartmouth was in sharp contrast to the delirious celebration I imagined must be happening across the river in Brooklyn. The Dodgers had finally beaten the New York Yankees in a World Series, and their years of frustration were over. I wondered if mine were just beginning.

They were. I have led a checkered life since 1955, and many times I have regretted not having persevered and stayed a little longer in an effort to solve my problems.

Shortly after the graduation of the Class of 1958 (my class), the ALUMNI MAGAZINE began arriving at my home in Pennsylvania. Wherever I was, my mother sent it on to me. Initially I accepted it, and I ignored it. Its pages held bittersweet memories, and I couldn't look to see what my classmates were accomplishing while I was in limbo. I couldn't even understand why I was getting the magazine. I was a dropout, a living example of one who couldn't make it; this magazine was for graduates, not for losers.

This stage passed and I began to read and the memories drifted back and they were warm and good. I began checking the '58 column for word of some of the few classmates whom I might have known and who, I hoped, would remember me. It wasn't always easy to read of men my own age moving up the corporate ladders while I wandered through my hitch in service, an overseas tour, and two other colleges, finally settling on a career in state government. No reflection here — there's nothing dishonorable about government service, but it palls next to a vice presidency of CBS, a diplomatic appointment, or authorship of a book.

At one point, however, my attitude changed. I noticed, with some shock, an article about a Dartmouth man who had not graduated. I hadn't thought the ALUMNI MAGAZINE was concerned with non-graduates. Inspired, I thumbed through back issues, making the same discovery. Putting the magazine aside, I looked back at the last few years in a new light. The guilt and the shame I had carried with me for years diminished. I remembered a professor telling me, "Once a Dartmouth man, always a Dartmouth man." It seemed at the time a nice thing to say, but I doubted that anyone at the College remembered alumni other than those who had succeeded in finishing the four years. Now, seeing those articles about men who had been in Hanover only briefly made me look again at myself and my Dartmouth experience.

From matriculation in 1954 until the day I left, I was taught by sincere, dedicated men; although my grades were low, I have retained subconsciously through the years much of their wisdom and their wit. Coming from Dartmouth gave me an edge that I had never realized. Being part of a relatively small group of men (there were about 2,700 undergraduates then) in the wilds of New Hampshire - studying and learning far from urban life, growing up strong and wise in an isolated environment — was great training for those times to come when I would be alone against the world, making my own decisions and facing life with the strength of inner peace and determination that made survival just a little bit easier. Among other things, as an ex-Dartmouth student — an Ivy League jock — I was sort of a novelty on the two service football teams and the two semi-pro outfits I played with. It gave me a mystique, albeit a minor one, since I was never a star in the 17 years I played the game.

There are, however, drawbacks to my background. My family had encouraged reading, and the Dartmouth atmosphere enhanced it. It was part of the heritage, having books always around, and as I wandered through Baker Library, I felt the whole world, past and present, there before me in the stacks. But the world of which I am a part is 95 per cent high-school- educated or below; most of my co-workers regard bookishness with suspicion. I am in a sort of limbo: lacking the paper which makes me officially educated; but, having more than just "street smarts," not uneducated either.

I walk this middle path, though, and somehow there is within me a peace, almost a smugness, because of the knowledge I have, the culture to which I have been exposed, and finally, the fact that even in the most discouraging educational vacuum, there are always 20 or 30 people with whom I can exchange ideas. This smugness, this unspoken feeling of superiority, is a weak point I must constantly guard against because the same people I knock for not reading a book or for lacking conversational depth do their jobs as well as — and, in many instances, better than — I do. Consequently, I must compromise and I have learned to do so with increasing effectiveness. Dartmouth demanded excellence but never suggested its students should denigrate others not so fortunate.

Temporarily I have resigned myself to my present economic state. But the bills are paid and the house is warm and the family is happy and Dartmouth lives on in my mind, a pleasant memory and, because of its being and my having been there, a reason for hope.

There was never a man who knew the Dartmouth songs better than I and few who enjoyed the stillness of a winter night on the campus more. To me, Hanover is not only a geographical location, but a state of mind. The memories of Thaddeus Seymour entering the classroom in a Sherlock Holmes greatcoat and hat, Ralph Flannagan's orchestra playing in the gym, bluebooks and parkas, Lou Turner and Leo McKenna and Bernie Fulton on the gridiron, Dick Fairley and Gene Givens and Ron Judson on the court, fraternity rush, John Sloan Dickey, and 212 Woodward Hall remain in the corridors of my mind, a constant source of pleasure and satisfaction.

From Hanover to Washington to Libya to France and Germany, through the Louisiana bayous, and finally, after a few detours, to the Susquehanna Valley and Harrisburg, the flame of Hanover persists and enriches my life. Now, 22 years after matriculation, I feel no more sadness, no more regrets, only the knowledge that whether I ever see Hanover again or talk with another Dartmouth man, I have had a quarter-slice of life that most have not. I have walked your way once, Dartmouth; I have been part of the scene for a little while; and for this I will be eternally grateful.

Robert Zovlonsky lives in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA simple mental technique... A simple mental tech... A simple mental... A simple...

February 1977 By PIERRE KIRCH -

Feature

FeatureNever Let Go

February 1977 -

Feature

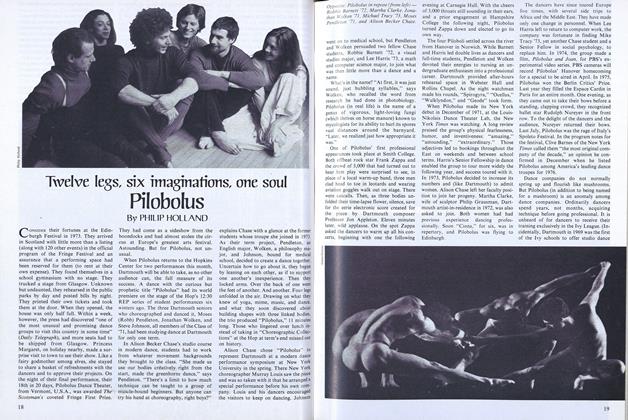

FeatureTwelve legs, six imaginations, one soul Pilobolus

February 1977 By PHILIP HOLLAND -

Feature

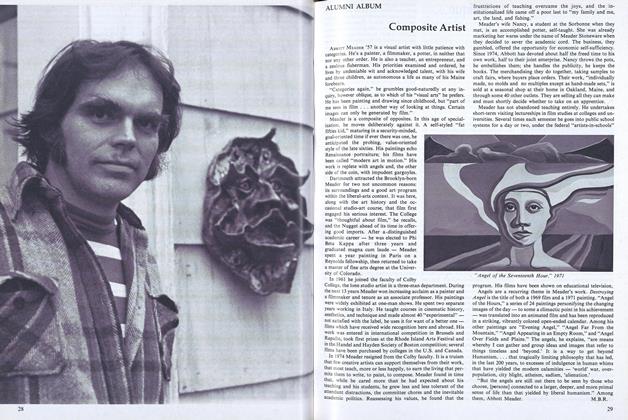

FeatureComposite Artist

February 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleStepping Out with a Bounder

February 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleGray Is Beautiful

February 1977 By ELIZABETH CRONIN '77