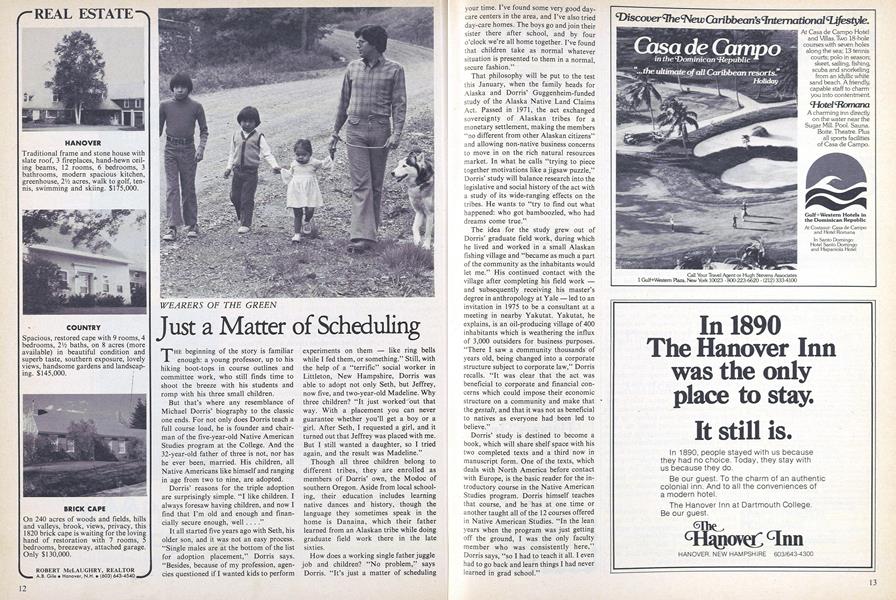

THE beginning of the story is familiar enough: a young professor, up to his hiking boot-tops in course outlines and committee work, who still finds time to shoot the breeze with his students and romp with his three small children.

But that's where any resemblance of Michael Dorris' biography to the classic one ends. For not only does Dorris teach a full course load, he is founder and chairman of the five-year-old Native American Studies program at the College. And the 32-year-old father of three is not, nor has he ever been, married. His children, all Native Americans like himself and ranging in age from two to nine, are adopted.

Dorris' reasons for the triple adoption are surprisingly simple. "I like children. I always foresaw having children, and now I find that I'm old and enough and financially secure enough, well...

It all started five years ago with Seth, his older son, and it was not an easy process. "Single males are at the bottom of the list for adoption placement," Dorris says. "Besides, because of my profession, agencies questioned if I wanted kids to perform experiments on them - like ring bells while I fed them, or something." Still, with the help of a "terrific" social worker in Littleton, New Hampshire, Dorris was able to adopt not only Seth, but Jeffrey, now five, and two-year-old Madeline. Why three children? "It just worked out that way. With a placement you can never guarantee whether you'll get a boy or a girl. After Seth, I requested a girl, and it turned out that Jeffrey was placed with me. But I still wanted a daughter, so I tried again, and the result was Madeline."

Though all three children belong to different tribes, they are enrolled as members of Darris' own, the Modoc of southern Oregon. Aside from local schooling, their education includes learning native dances and history, though the language they sometimes speak in the home is Danaina, which their father learned from an Alaskan tribe while doing graduate field work there in the late sixties.

How does a working single father juggle job and children? "No problem," says Dorris. "It's just a matter of scheduling your time. I've found some very good daycare centers in the area, and I've also tried day-care homes. The boys go and join their sister there after school, and by four o'clock we're all home together. I've found that children take as normal whatever situation is presented to them in a normal, secure fashion."

That philosophy will be put to the test this January, when the family heads for Alaska and Dorris' Guggenheim-funded study of the Alaska Native Land Claims Act. Passed in 1971, the act exchanged sovereignty of Alaskan tribes for a monetary settlement, making the members "no different from other Alaskan citizens" and allowing non-native business concerns to move in on the rich natural resources market. In what he calls "trying to piece together motivations like a jigsaw puzzle," Dorris' study will balance research into the legislative and social history of the act with a study of its wide-ranging effects on the tribes. He wants to "try to find out what happened: who got bamboozled, who had dreams come true."

The idea for the study grew out of Dorris' graduate field work, during which he lived and worked in a small Alaskan fishing village and "became as much a part of the community as the inhabitants would let me." His continued contact with the village after completing his field work - and subsequently receiving his master's degree in anthropology at Yale - led to an invitation in 1975 to be a consultant at a meeting in nearby Yakutat. Yakutat, he explains, is an oil-producing village of 400 inhabitants which is weathering the influx of 3,000 outsiders for business purposes. "There I saw a Community thousands of years old, being changed into a corporate structure subject to corporate law," Dorris recalls. "It was clear that the act . was beneficial to corporate and financial concerns which could impose their economic structure on a community and make that the gestalt, and that it was not as beneficial to natives as everyone had been led to believe."

Dorris' study is destined to become a book, which will share shelf space with his two completed texts and a third now in manuscript form. One of the texts, which deals with North America before contact with Europe, is the basic reader for the introductory course in the Native American Studies program. Dorris himself teaches that course, and he has at one time or another taught all of the 12 courses offered in Native American Studies. "In the lean years when the program was just getting off the ground, I was the only faculty member who was consistently here," Dorris says, "so I had to teach it all. I even had to go back and learn things I had never learned in grad school."

Now that the program is off the ground with what he calls "consistent help and support of the administration and faculty," teaching duties are shared with two other professors, both of whom have co-appointments with other departments - like his own with anthropology. This means Dorris can teach what he likes, which for him is the Contemporary Native American Societies course. "We cover federal Indian law, Native American issues dealing with natural resources, stereotyping, everything," he says. One of the ways he brings students into the mainstream of the course is by gameplaying, a method he has packaged and will publish within the year. One popular game, the one with which he often opens his Contemporary Societies course, is the law game. "Everyone has a role - there is a leader, a rival, workers, bosses, children, criminals. Anyone may write a law on the blackboard - such as 'no killing' - and anyone else may erase that law if he disagrees with it. We go on this way for two hours, and it can really get quite violent." In the most recent staging of the law game, he adds with a laugh, "the only law left on the board at the end of the hour was 'Children must obey their parents.' "

Though Native American Studies is a recognized College program offering a modified major, Dorris notes that "we really had to prove ourselves in the beginning. People thought of Native American Studies as some kind of pop ethnic-studies major, or of existing only for native students. But the program was founded with the idea that it was an academic discipline, open to all students." The program recently received a $200,000 grant from the Educational Foundation of America to fund student interns doing research and Field work in Native American Studies.

Even at home, Dorris has had to contend with misunderstandings about Native Americans. "There was a library that called up to see if the kids could dance for some program they were having," he says ruefully. "And a woman called the other night to see if I could teach her husband how to tan deerhide." Does such stereotyping, which he tries to counteract in his courses, annoy him? "The only thing that bothers me is when people are intentionally cruel about, say, using the Indian symbol. But generally, though, students have listened when Native Americans say it is offensive to them."

While the seemingly inexhaustible Dorris cheerfully says he has "no spare time," he admits to relaxing with mystery stories, "junk books," and television. "But really," he says, "I have three children, three books, and a full course load. Most of the time, that's plenty."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMen and Women: What's the Difference?

October | November 1977 By Dan Nelson, Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Singing of the Cider

October | November 1977 By Sanborn Brown -

Feature

FeatureThe Bakke Case

October | November 1977 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

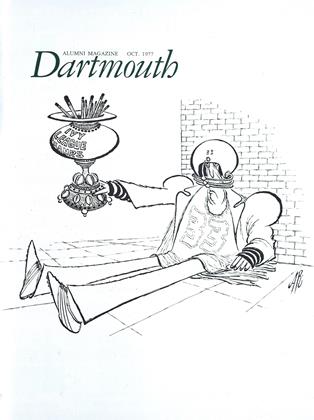

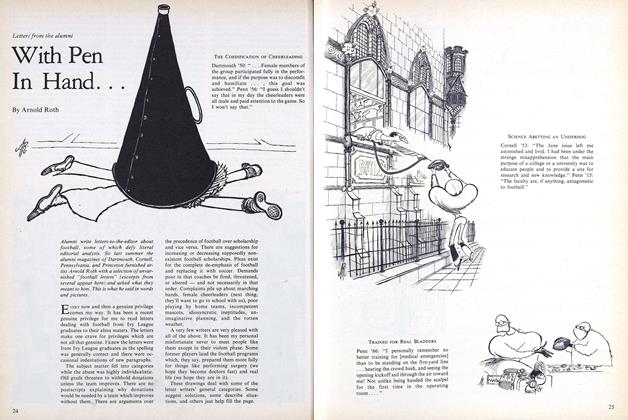

FeatureWith Pen In Hand...

October | November 1977 By Arnold Roth -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

October | November 1977 By THOMAS G. JACKSON -

Article

Article"My hardships were excessive"

October | November 1977