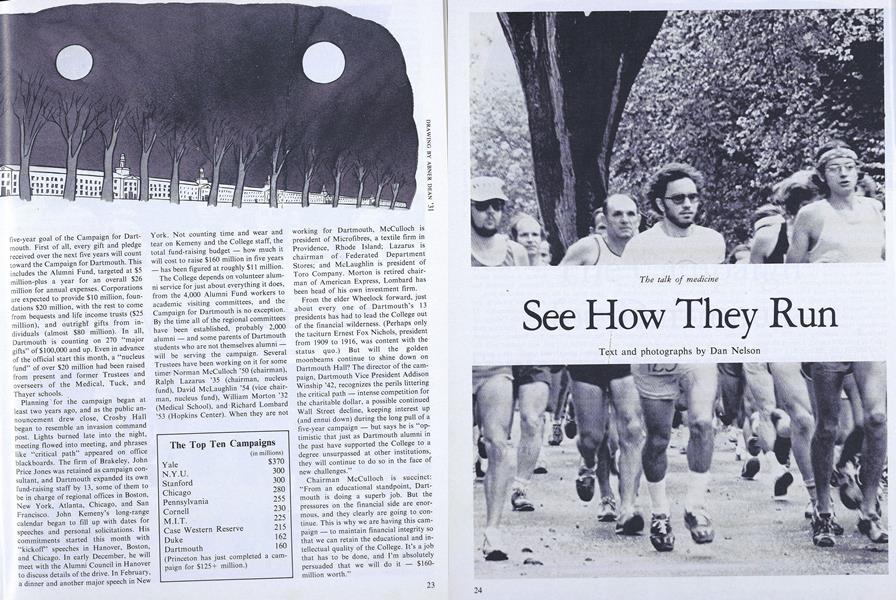

ANYONE who reads "Peanuts" or "Doonesbury" knows that recreational running is serious business. What in other places may be the obsession of a conspicuous few is, in Hanover, an epidemic. This is a town where the latestmodel training shoe is a status symbol, where an Adidas warm-up suit passes for casual attire, where the locker room in Alumni Gym is a popular spot to meet for a lunch break consisting of a trot around the golf course, and where something on the order of 600 pairs of running shoes - not to be confused with tennis or other sports shoes - are sold in a good month.

This is also a doctors' town, with an abundance of physicians to attend to shin splints, torn muscles, pulled ligaments, and fallen arches. (Runners tend to be a hypochondriac lot, given to complaining about the slightest twinges. Considering the demands they make of their bodies, it is not surprising.) Some of the doctors at Mary Hitchcock Hospital and the Medical School, runners themselves, were concerned about an increase in the number of running-related injuries. Certainly the number of runners on the roads is growing, as any Hanover driver can attest, but the medical men felt that many of the injuries, and consequent- complications, were the result of ignorance. Apparently, many beginning runners, and even ambitious veterans, don't know how to begin or build a training program and end up pushing themselves to what is literally a breaking point. And once they get hurt they don't know what to do about it. The walking wounded either grit their teeth and keep on the same as before, compounding, the damage, or they give up in frustration, depriving themselves of the pleasures and benefits of the best of exercises.

So, in early October, the doctors organized a seminar. Speakers and sponsors were recruited and closed-circuit television coverage was arranged. Although the healthy young couple gracing the advertising posters looked like people out of Caribbean-vacation ads and not like tired, sweaty runners, it still was a surprise to see 200 enthusiasts gathered in Kellogg Auditorium at 8:00 on a rainy Saturday morning the day before the Medical School's AAU-sanctioned 26-mile marathon.

The first speaker, Dr. Perry Leary, a pharmacologist visiting from South Africa, admitted candidly that the health benefits of running are largely unproved. He professed a great faith in running's value, however, and remarked that regular competition in a 56-mile ultramarathon" hadn't done him any permanent harm. He certainly looked to be fit and trim, although vaguely cadaverous, and in other respects seemed quite normal.

There is increasing evidence, he said, that running is good for treating psychoneurosis and that regular exercise is superior to tranquilizers - also cheaper and safer - in the treatment of depression. Runners might also be happy people because they "are not constipated, as a rule" - due to the effect exercise has on releasing magnesium into the bowel - and what's more, they aren't likely to develop gout.

"Americans are the most obese, sedentary people I've ever come across, Dr. Leary said. "Obesity is a life-shortening disease," but it's preventable, he added. Exercise, particularly running, helps one lose weight, improve muscle tone, and achieve physical well-being. But he conceded that running isn't a cure-all. Runners don't seem to have any more immunity to cancer than the rest of the population, they suffer more muscle and joint injuries than the average rocking-chair sitter, they sometimes develop cardiac arrhythmia - "nothing to be too worried about" - and, depending on when and where they run, might suffer a little frostbite, heatstroke, or dehydration.

Dr. Donald Andresen, a cardiologist, came equipped with a plethora of complicated charts and graphs. The gist of what he said suggested that the ability of the cardiovascular system to deliver oxygen is the main determinant of a runner's performance; that women, because of their generally smaller lung capacity and lower maximum cardiac output, have to work harder to increase their performance than do males; that well-conditioned athletes have larger hearts than non-athletes because heart volume increases in relation to oxygen transport requirements; and that as the ability to transport oxygen increases, so does the body's ability to extract oxygen from the blood. He said that distance running or cross-country skiing are just about the best activities for increasing cardiovascular performance.

According to Dr. Paul Beisswenger, who talked about metabolic fuels, the average body has about 2,000 calories of glucose stashed away, along with some 140,000 calories of fat, and about 40,000 calories of protein - calories more or less available depending on the condition of the machine burning them. In any kind of distance event, it is to the runner's advantage to be able to burn those plentiful fat calories, and the ability to do so efficiently improves with training. The doctor also described a way, called "carbohydrate loading," for marathon runners to top-off their calorie tanks. The idea is to stockpile some extra glycogen calories. Train hard for three 5 days and eat a low-carbohydrate diet. If Then, three days before the race, ease up on training but put away a daily total of 5,000 calories on a 50-per-cent carbohydrate diet. Stoke up once more, three to four hours before the event, with a high-carbohydrate snack.

Joan Tomasi, from the Mary Hitchcock Nursing School, gave a talk on the woman runner - "Freedom From Fat and Fatigue." She recounted some archeological evidence that women participated in early athletic events (women runners in the Greek's Heran Games ran with one breast exposed - an early counterpart, Tomasi guessed, of today's chromosome tests) and deplored the more modern restrictions on female athletes. In 1928, women were first allowed to run in the Olympics, but only in the sprint events, and the notion that women can't handle the longer distances still persists. They were allowed to compete in the 800-meter race in the 1964 Olympics and then in 1972 they were allowed to run 1500 meters, still more of a sprint than an endurance contest and still the longest distance in the Olympics for female runners. The first woman ran the Boston Marathon in 1967 - an unofficial entry who had to run with a bodyguard to keep the race's organizers from pulling her out - and the first women entered officially in 1972.

The social and psychological restrictions on female runners are more of a problem than any biological constraints, Tomasi claimed. "There are no particular or peculiar injuries to women runners. A well-conditioned female athlete doesn't develop injuries any differently from well-conditioned male athletes." Her one word of caution was that since most American women are in relatively poor physical condition (most men probably are, too), they should pay careful attention to a gradual conditioning program.

Dartmouth Track Coach Ken Weinbel had some hints on how to "run for gain, not for pain," for runners of both sexes. Weinbel's emphasis was on a gradual training program, on running for fun and for health. He advised making an investment, before taking a single stride, in good shoes specifically designed for running, and made suggestions on what to look for in fit, flexibility, and padding. (A recent issue of Runner's World magazine devoted 60 pages to a review of running shoes - shoes ranging in price from $20 to $40 - and a ranking of the top 25 training flats.) Weinbel recommended eating a well-balanced diet, of course, and getting plenty of rest. "We find good rest is correlated with performance."

The coach's advice for beginning runners was to "just move, in a joggingtype motion, for three minutes, then walk three, then jog, and so on, for 20 minutes. You can build up from there. Pretty soon you'll be running more than walking." He also recommended basic yoga stretching exercises before and particularly after a run. He described a' suitable weighttraining program - "We believe in weight training for the male runners as well as the women" - and advocated "rest-running" - "Go out and look at the mountains, count the cows, and have a good time" - in alternation with days of more rigorous training. "You must enjoy it," he concluded.

Kirk Randall, a marathon runner who won the Medical School marathon in 1975 and the 12-mile race this year, added some advice for experienced runners (he doesn't like the word "jogger"). He finds it best to run every day at a regular time and to run by time - perhaps for an hour a day - and not by a set distance to be covered at a faster and faster pace. ("You'll run yourself into the ground that way.") The pace ought to be slow enough for the runner to carry on a conversation, but it should be varied with occasional bursts of acceleration and sometimes even walking breaks. Randall also said that running hills is a good way to get in a good workout in a short time and that stretching is most important - at least 15 minutes' worth after a run. Competitors should set realistic racing goals, looking to their own improvement and not so much to beating the pack. He talked about motivational aids for keeping at running - like a desire to develop better eating and sleeping habits - and described some possible "rewards" to indulge in after a particularly hard workout or good race - like "eating pizza or getting plastered."

Dr. Robert Porter, an orthopedic surgeon, said there are ten million runners in the U.S. and that a good portion of them suffer from a variety of knee, achilles tendon, shin, ankle, and heel complaints - mostly the result of "cumulative impact loading." The impact load on the knee can be considerable - the patella takes four times the body weight during each stride. It figures that "if your leg is out of alignment, you're going to have problems" but that "if you have a nice, V-shaped patella, nice slot, and nice Q-angle, you're in good shape."

The most common mistakes made in training, Porter said, are in going beyond capacity, increasing mileage rapidly, changing technique, running too much too soon on hard surfaces, not getting enough rest, and not preparing with adequate strengthening and stretching. According to Porter, an injured runner probably won't have to lay off completely, despite the claims of most doctors, "who don't understand sports medicine. Porter acknowledged the fact that injured athletes don't like to be told to stop training." Depending on the injury, hobbled runners can often manage by training gently or changing their routine. Five miles of biking and a quarter mile of swimming, for example, give the exercise equivalent of a mile of running.

Dr. Thomas Shirreffs, also an orthopedic surgeon, who talked about that "vulnerable area between the knee and the foot," seemed to be saying that if an injury is sustained there, only rest seems to help. A podiatrist, Dr. William Ferriter, had lots of pictures of bruised, swollen, twisted, and otherwise sore feet, and threw around words like "pronation," "supernation, and "resupernation." He observed that as far as the foot is concerned, walking or running is by no means an easy task.

By this point, the audience seemed to find that sitting was not an easy task, either, and the concluding speaker's remarks were happily brief. Dr. Stuart Russell, an orthopedist, emphasized the "go-easy" philosophy. Although pregnant women, men over 100, people with artificial legs, and blind individuals have completed marathons, he said, "We were not all made to run." And he added, if you do decide to run, "Run for your health, but run in good health."

The talk of medicine

Dan Nelson '75, an assistant editor of theALUMNI MAGAZINE, runs about 40 milesevery week - and is known to take longlunch-hours in the process.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFie on the Flush Toilet

November | December 1977 By Harold H. Leich -

Feature

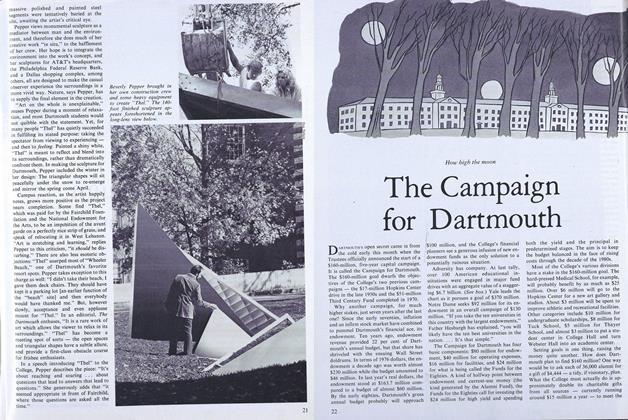

FeatureThe Campaign for Dartmouth

November | December 1977 -

Article

ArticleThe DCMB Double-entendre March

November | December 1977 By Anne Bagamery -

Article

ArticleDick's House Is Her House

November | December 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleTheir Fathers' Sons

November | December 1977 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

November | December 1977 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON

Dan Nelson

-

Feature

FeatureHigh On Your Dial

December 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

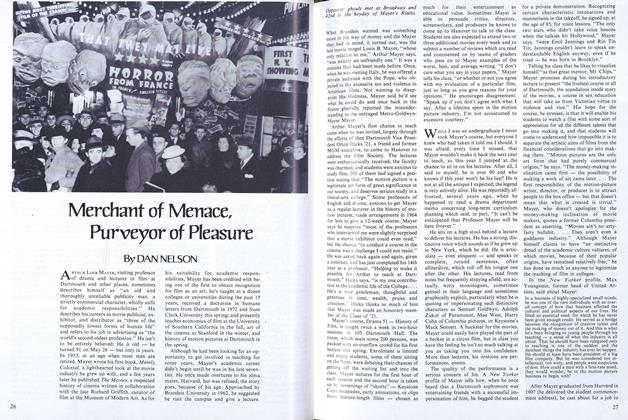

FeatureMerchant of Menace, Purveyor of Pleasure

JUNE 1977 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureShhh. There still are idealists abroad and they're called the Peace Corps

JUNE 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

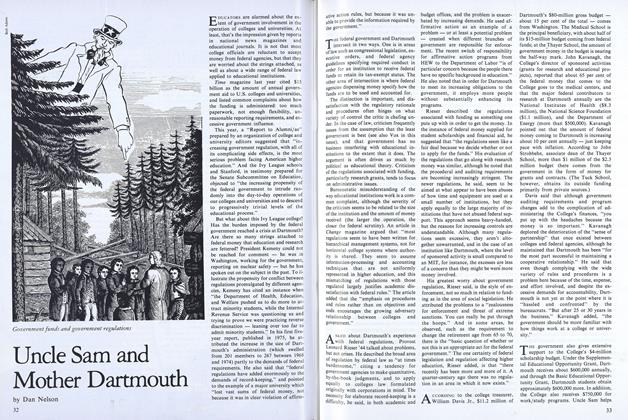

FeatureUncle Sam and Mother Dartmouth

November 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

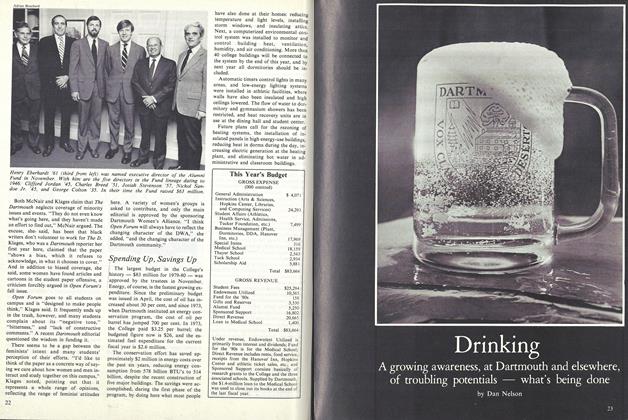

FeatureDrinking

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson

Features

-

Feature

FeatureArt Collector and Author

APRIL 1968 -

Feature

FeatureThree in the Theater

APRIL 1971 By BARBARA BLOUGH -

Feature

FeatureThe Wallace Affair

JUNE 1967 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureThe Library Revolution

MAY 1968 By Clifford L. Jordan '45 -

Feature

Feature'... A whole pool of frustration, anger, resentment...'

February 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Mar/Apr 2005 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74