LOGGING RAILROADS OF THE WHITE MOUNTAINS by C. Francis Belcher '38 with a foreword by Sherman Adams '20 Appalachian Mountain Club, 1980. 242 pp. $8.95

This is no book for sentimentalists, least of all for those given to nostalgic imaginings of some vanished New World Eden, an America of "the good old days" when "rugged individualism" was a way of life and Social Darwinism very nearly an article of faith. For all its 80-odd period-piece photographs of old steam engines and lumber camps, for all its lively anecdotes of gangs of bearded lumberjacks with macho names the "Bangor Tigers," one group was called for all its depiction of iron-willed lumber barons wheeling and dealing in a laissez-faire age, Belcher's book evokes little nostalgia. The response is rather dismay, plus a generous admixture of retrospective outrage, at the unrestrained human rapacity which despoiled vast areas of New Hampshire's forests.

Belcher's story is only partly about railroading; the rest of it is the stuff of tragedy. It begins in 1867, when the New Hampshire General Court enacted legislation permitting the sale of all state-owned public lands to private purchasers. The treasure trove having been opened, the lumber barons, corporate and individual, invaded New Hampshire, and human inventiveness readily supplied them with the one machine that could make human avarice efficient: the steam engine. Soon log- ging railroads began to snake their way through the notches, along remote stream-beds, and up hills to backwoods lumber camps; and the steam engines began hauling millions of board feet of logs 650 million in 1907 alone, Belcher estimates down twisting mountain ravines to valley mills and markets.

In just a little over 40 years, mountain by mountain, range by range, several hundred thousand acres of virgin fir and spruce were systematically, efficiently destroyed by the "wood butchers," as they came to be called. One logging firm alone, Belcher writes, cut over at least 70,000 acres. The principal agent of destruction was clear-cutting, a practice whereby loggers simply "cut down everything in the woods and trimmed and dragged off the marketable timber, leaving the remainder as slash." What human short-sightedness started, nature finished, for the slash provided admirable tinder .for fires. Naturally, then, immense forest fires periodically swept the mountains, especially during the disastrous years of 1907 and 1908, some ignited by lightning but most, it would seem, by the spark-belching steam engines. The fires respected no manmade property lines; they destroyed unlumbered stands of virgin timber and cut-over areas indiscriminately. "The scars from this era," as Belcher writes, "will still be visible years from today. Go anywhere into the backcountry of the White Mountains and you will see these reminders." For one place, try the Pemigewasset area. Next time you go over the Kankamagus Highway, have a look at the mountains. You can't miss the old fire lines.

But at the heart of tragedy is surely irony, and in the final accounting, Belcher concludes, we actually owe the "wood butchers" a debt of gratitude. For ironically, it was by their very excesses that they sowed the seeds of their own eventual nemesis. The devastation they created was so extensive and so highly visible that it led inevitably to widespread demands for congressional action. The result was the Weeks Act, which not only saved the remaining forests by converting large areas of northern New Hampshire into the White Mountain National Forest but also marked a major beginning step toward the creation of our present-day national-forest concept. Thus the tragedy worked itself out according to the ancient principles: out of hubris, finally, nemesis; out of defeat, victory "as the mountains were saved and put in trust for future generations." But, as in all tragedy, at how great a cost!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDeath and Reunion: the loss of a twin

June 1981 By George L. Engel -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Long-Deferred Promise

June 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureRockefeller Center: the ideal of reflection and action

June 1981 By Donald McNemar -

Feature

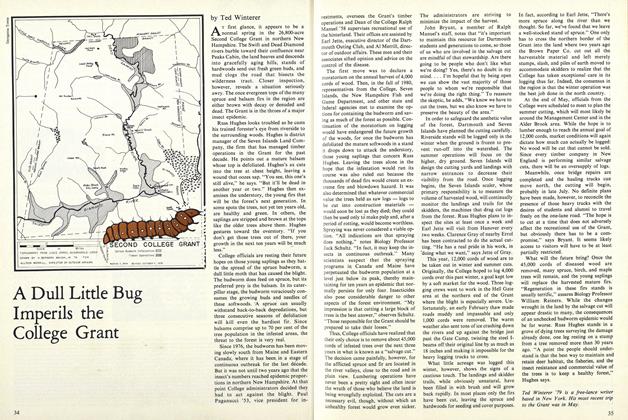

FeatureA Dull Little Bug Imperils the College Grant

June 1981 By Ted Winterer -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

June 1981 -

Article

ArticleThe National Committee

June 1981

R. H. R.

-

Books

BooksNotes on a launching: a new journal, not for the literati alone, but for the literate, one and all.

September 1978 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksNotes on Mr. Eliot's Algonquian Bible, a Birthday Gift for Mr. Baker's Library

December 1978 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksSun to Sun

March 1979 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksMythogenic

JAN./FEB. 1980 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksNot for Art's Sake

APRIL 1982 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksMan in the Cambric Mask

JUNE 1982 By R. H. R.

Books

-

Books

BooksShelf Life

July/August 2011 -

Books

BooksRAYMOND OF THE TIMES

October 1951 By Arthur M. Wilson -

Books

BooksFreezing Points of Anti-coagulant

February 1936 By David I. Hitchcock '15 -

Books

BooksTHE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF EDWARD GIBBON.

July 1961 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Books

BooksFaculty Books

July 1953 By LOUIS O. FOSTER -

Books

BooksEARLY ENGLISH CHURCHES IN AMERICA

November 1952 By ROY B. CHAMBERLIN