ROBERT FROST AND SIDNEY COX:

Forty Years of Friendship Edited by William R. Evans '60 University Press of New England, 1981 297 pp. $10

This book is a collection of letters, 146 of them, the surviving record of a friendship of 40 years duration between two remarkable men: Robert Frost, poet, and Sidney Cox, teacher. The letters became part of the Frost collection at Baker Library in 1953 when Alice Cox, widowed then for over a year, donated them to the College. In spite of their considerable value in the literary marketplace, she wrote Frost, "I just couldn't sell Sidney's friendship with you."

It seems unlikely that this book will require any major adjustments in prevailing views of Robert Frost. If the literary specialist takes up the book to glean new information on Frost's life or to seek new insights into the poet's mind or art, he is likely to be disappointed. For one thing, of the total of 84 Frost letters printed in this book, nearly half— 41, as my quick collation tells me have been available in print in virtually the same form for some time, 38 of them in Lawrance Thompson's edition of the Selected Letters of Robert Frost (1964), and three in Thompson and Edward Connery Lathem's Robert Frost:Poetry and Prose (1972). Moreover, the remaining 43 letters from Frost to Cox, though printed here for the first time, to be sure, seem to reveal very little about the poet's mind or temper that Lawrance Thompson had not previously analyzed in some detail in his exhaustive, definitive three-volume biography of Frost (1966, 1970, 1976).

Indeed, the Frost letters in this book serve in large part, it seems to me, to corroborate many of Thompson's less flattering conclusions about the harsher, calculating side of Robert Frost: his intense selfcenteredness; the use of his friends to promote his own books or to get him speaking engagements; his characteristically harsh judgments on his living poetic peers (Sandburg, Masters, Alfred Noyes, W. H. Davies); the scornful, hectoring quality which he often displayed even, or perhaps especially, to those he knew best.

But if the book offers little new grist for the scholars' mills, general readers particularly those many hundreds of Dartmouth general readers who knew Sidney Cox as teacher and counted him friend have ample cause to be grateful to William Evans. For his book is not, after all, about Robert Frost alone but about Robert Frost and Sidney Cox. And during the 25 years that he taught literature and creative writing at Dartmouth, from 1926 until his death in 1952, Sidney Cox profoundly challenged, in that socratic, gadfly way that only he could challenge, the minds and spirits of the best and the brightest among several generations of undergraduates. He was, in short, as Frost himself testified, "a great, a triumphant teacher."

What, then, do these letters reveal about the 40-year relationship between Frost and Cox? Among other things, that it was ail unequal one. From start to finish Frost's was the dominating personality, Cox's the dominated. Frost demanded, took, insulted, scorned, bullied. Cox questioned, acceded, apologized, placated, knuckled under. Much is epitomized in an exchange of letters in late 1928 when Cox submitted for Frost's approval the partial mansucript of a book he proposed on his conversation's with the poet. Frost's response was brusque, under the circumstances insulting even; "It won't do. ... I don't like the picture it makes of either of us. ... I might have to search myself for my reason in singling you out for a conversation a year. I can tell you offhand I never chose you for a Boswell. Maybe I liked your awkwardness, naivete, spirituality. We won't strain for an answer." That after 17 years of friendship! Cox's soft reply was also characteristic: "You won't make the easy mistake of suspecting that I wanted to be a mereBoswell even though I was probably selfconscious. ... I should think you might see how I could feel you to be my best friend, and still look up to you. I won't even admit that looking up is all weakness or silliness. But I am sorry I am so easily impressed, that I capitulate too completely." Frost won almost too easily; Cox never even submitted his manuscript to a publisher, not in that form, anyway.

Seldom have differences between friends, differences in temperament, taste, and outlook, been so sharply defined. Both men recognized the situation. Frost summed it up retrospectively four years after Cox's death: "Our intimacy was a curious blend of differences, ... " he wrote in an unpublished preface for Cox's posthumously published book about Frost, A Swinger ofBirches. "We were a strange pair in our atvariances."

And yet, and yet. ... In spite of differences their friendship remained, solid if uneven, enduring if troubled. That, too, is undeniably demonstrated by these letters, for they "are themselves proof that neither man left the other," as James M. Cox (no relation to Sidney) writes in his foreword.

"They show that Frost no more gave up being a teacher than Sidney Cox gave up being a student. If the true measure of Frost's teaching is to be found in the wisdom he imparted in these letters, the measure of Cox is that he both inspired and received it."

Nevertheless, from these letters, it is difficult to escape one conclusion: Frost was the better writer that goes without saying; but Cox was the better man.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryJust a suggestion, Mr. President: an agenda for the eighties

October 1981 -

Feature

FeatureCarlos Fuentes: Of isolation, of connection

October 1981 -

Feature

FeatureSubmariner

October 1981 By M. B. R -

Article

ArticleDeaths

October 1981 -

Article

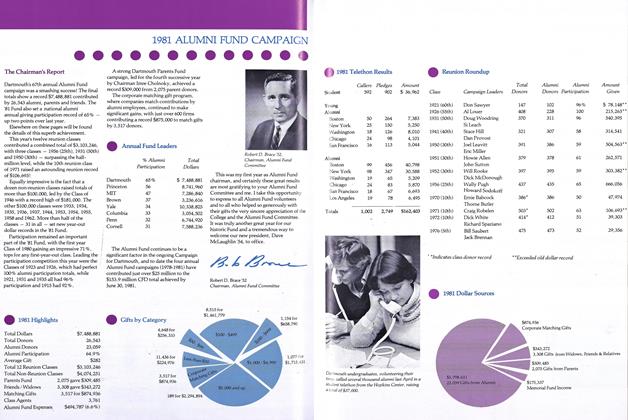

Article1981 ALUMNI FUND CAMPAIGN

October 1981 -

Article

ArticleWearers of the Green

October 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77

R. H. R.

-

Books

BooksNotes on a launching: a new journal, not for the literati alone, but for the literate, one and all.

September 1978 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksSun to Sun

March 1979 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksLooking Back

April 1979 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksIntolerable Ambiguity

November 1980 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksWood Butchers

June 1981 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksWhat If?

June 1981 By R. H. R.

Books

-

Books

BooksNew Modern Poets

JUNE 1967 -

Books

BooksFAMOUS FIRST FLIGHTS THAT CHANGED HISTORY.

APRIL 1969 By DOUGLAS F. STORER '21 -

Books

BooksPHYSICAL CHEMISTRY FOR STUDENTS OF BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE

June 1933 By John P. Amsden -

Books

BooksGUIDE TO PEDAGUESE.

APRIL 1965 By RICHARD G. JAEGER '59 -

Books

BooksBASIC PRINCIPLES IN EDUCATION

December 1934 By Robert Bear -

Books

BooksRUDOLPH THE RED-NOSED REINDEER SHINES AGAIN.

November 1954 By SIDNEY C. HAYWARD '26