Notes on a rival of matrimony: the compromises, betrayals, and felicities of translation.

February 1977Notes on a rival of matrimony: the compromises, betrayals, and felicities of translation. February 1977

IN THIS column last month we had some words to say about the difficult art of literary translation, particularly as practiced by Gregory Rabassa '44. And now this month, right on cue, as pat as the hero's entrance at the climax of a melodrama, two more translations by another practitioner of the art have come across the desk. We claim no prescience, just a bit of luck, for they both underscore last month's conclusions and suggest several new dimensions.

This time the translator is Walter Arndt, Professor of Russian Language and Literature, and the books are his newly published translation of the Selected Poems of Anna Akhmatova and the only slightly less recent verse translation of Goethe's Faust. "An amazingly gifted polymath," as a New York Times reviewer called him, Arndt won the Bollingen Prize in 1963 for his verse translation of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin and has translated many other Russian and German poets, including Pasternak, Evtushenko, Heine, and Rilke.

Fortunately, Arndt is as adept at explicating the complexities confronting the translator as he is at translation itself. In the Faust, as he explains in an accompanying article, he attempted a feat that had never before been brought off: not only to translate Goethe's long dramatic poem (both Parts I and II) into English verse but to do so "with strict adherence to the form of the original in all its varied meters and rhyme patterns, and generally maintaining a strict line- by-line correspondence."

The difficulties were considerable, not the least being that the Faust is not only a long poem — unconscionably long, some would say — but an uneven one as well. Transcendent, majestic, and tragic in some sections, it also seems, Arndt concedes, flaccid, tedious, or bathetic in others. With such a work before him, the translator's first duty lies not in literal fidelity to the text. On the contrary, Arndt argues, equivalence often demands a "judicious departure from the original." One must "try to match the weak and flat spots of the original as well as its high points."

The translator's obligation, then, is of a higher order than fidelity to language, or fidelity even to what is commonly called meaning. His ultimate fidelity must be to the total experience of the poem, its tone, texture, mood, even prosody. He must bring this total experience over into another language, warts and all. Balanced on his high wire stretched taut between the poles of literal accuracy on the one hand and aesthetic sensibility on the other, the translator performs his act.

If he brings it off, the achievement is its own reward. Whereas "imitation is an ego trip," Arndt concludes, "translation is a service, offering only the rewards of craftsmanship exercised and enthusiasm transmitted." Or in his less solemn metaphor: "translation appears to rival matrimony in the myriad minute sacrifices, compromises, betrayals, and felicities which go into its fabric." (The Faust is published by W. W. Norton, New York, hardcover — $15; paper — $3.95; the Selected Peoms of Akhmatova by Ardis Press, Ann Arbor, cloth $10.95, paper $3.95.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA simple mental technique... A simple mental tech... A simple mental... A simple...

February 1977 By PIERRE KIRCH -

Feature

FeatureNever Let Go

February 1977 -

Feature

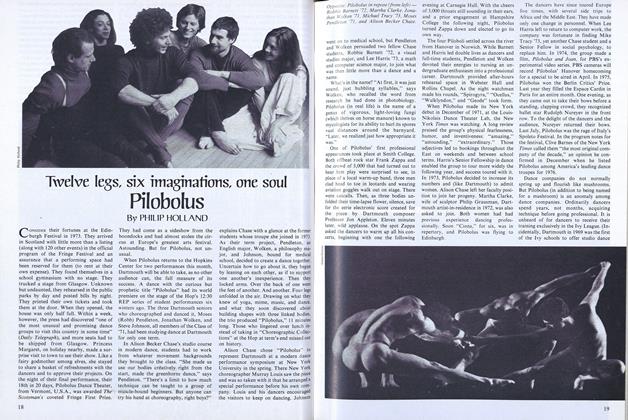

FeatureTwelve legs, six imaginations, one soul Pilobolus

February 1977 By PHILIP HOLLAND -

Feature

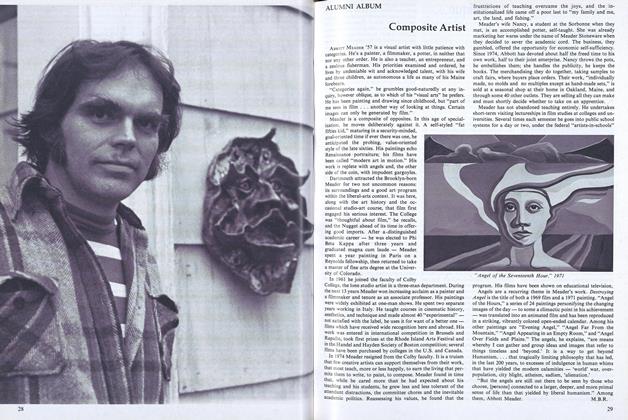

FeatureComposite Artist

February 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleStepping Out with a Bounder

February 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleGray Is Beautiful

February 1977 By ELIZABETH CRONIN '77

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

November 1956 -

Books

BooksTHE YOUNG MILLIONAIRES.

October 1973 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksAN INTRODUCTION TO MONEY AND BANKING

OCTOBER 1972 By MICHAEL R. DARBY '67 -

Books

BooksTHE DARTMOUTH BOOK OF WINTER SPORTS

January 1940 By Nathaniel L. Goodrich -

Books

BooksHOW WE DRAFTED ADLAI STEVENSON.

May 1955 By RICHARD W. MORIN '24 -

Books

BooksTraining in Citizenship

APRIL, 1927 By Robert E. Riegel