IF CARL BRIDENBAUGH '25 were masterminding the Bicentennial, the celebration would be substantially different. We would be "making a real play for good history instead of trying to make a buck." We would be emphasizing unity, the commonalty that made Americans peculiarly American long before the Revolution, instead of the diversity of our ethnic strains. Most of all, we would capitalize on the quickened interest in America's past to restore history to our schools, distinct from the ubiquitous "social studies."

Good history is what Bridenbaugh has been about throughout his distinguished 50-year career - as a teacher at every level from sixth grade through post-post-graduate, as author of 12 books and editor of four, as president of the American Historical Association, as founding director of the Institute of Early American History and Culture, established jointly by The College of William and Mary and Colonial Williamsburg.

An education major at Dartmouth, Bridenbaugh took only two history courses, neither in the colonial period. After two years at private schools, he joined the faculty of where he "taught a little of everything," from "The Voice of Science in Modern Poetry" to "The Far East in Modern Times." He went to Brown University in 1938, shortly after receiving his Ph.D-. at Harvard and coincident with the publication of his first book, Cities in theWilderness, honored by the AHA as the year's best work by a young historian. After war-time Navy service and five years at Williamsburg, he occupied an endowed chair in American History at the University of California, Berkeley, for 12 years. His return to Brown in 1962, to accept a newly created University Professorship, was prompted by a native easterner's homing instinct and the lure for a scholar of the John Carter Brown Library, which has, according to Bridenbaugh, "the greatest collection of books about and printed in America before 1801 of any repository, including the Library of Congress and the British Museum."

"The past... created day by day rather than date by date" was a phrase used to describe his work in the honorary degree citation accompanying the Litt.D. conferred by Dartmouth in 1958. "History is about chaps," Bridenbaugh likes to say. "What is history but the people?" he asks — people not in the Marxist sense of masses or classes, but of "individual men living and having their daily being, men acting in time and place."

"No great people," Bridenbaugh laments, "know less of their history than Americans." It is evoked - or warped self-servingly - but the grasp on a living past has been lost. "History tells us ..." is a favorite preface to a conclusion that will predictably corroborate the speaker's position. "Did the American Revolution Really Happen?" It is hard to tell, he suggests, from the variations bandied about this Bicentennial year.

Bridenbaugh attributes the nation's "historical amnesia" largely to a phenomenon he calls "the great mutation," which sets the 20th century qualitatively apart from preceding ages. In his 1962 presidential address to the AHA, he argued that the world has "witnessed the inexorable substitution of an artificial environment and a materialistic outlook on life for the old natural environment and a spiritual world view that linked us so irrevocably to the Recent and Distant Pasts. The change has been so radical, he said, that mid-19th-century western Europe and America had more in common with 5th-century Greece than with their modern successors.

American education has done little, he believes, to counteract the effects of "the great mutation." With the amorphous social studies, he blames part of our historical illiteracy on "worship at the shrine of that Bitch-goddess, quantification"; narrow analysis of trends and movements at the expense of cultural history; "the cult of the contemporary"; students who eschew excellence as undemocratic and professors who teach only what they must and that with "all the liveliness of a box of Shredded Wheat"; and over-specialization so excessive that an instructor may be unacceptable if "he's in the wrong decade."

The Bicentennial Bridenbaugh declares "a total flop." Given the opportunity to recreate historical imagination, "the Congress has failed and the country has failed." Instead of that "real play for good history," we have pageants and rampant commercialism. He sees a genuine, if largely unsatisfied, public interest in the nation's roots. His latest book, The Spirit of 76, which traces the growth of American patriotism during the 169 years from Jamestown to the Declaration of Independence, has met a brisk reception; he has many more invitations for Bicentennial lectures than he can accept. He has agreed to present the commencement address at Rhode Island College, which will confer an honorary L.H.D., according to the citation, on "the country's leading scholar in the field of colonial history."

Good history, that is — "history about chaps."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSelf-Evident Truths

May 1976 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Feature

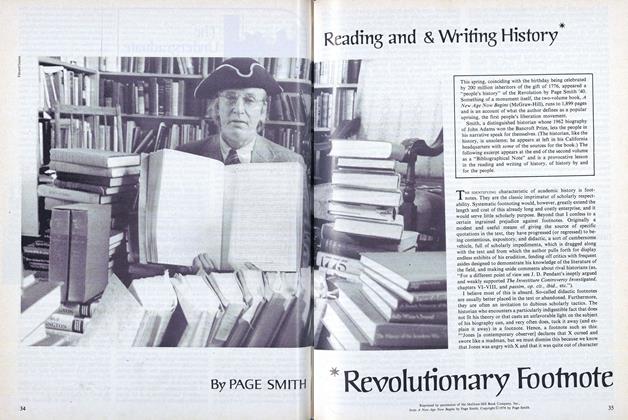

FeatureReading and Writing History and Revolutionary Footnote

May 1976 By PAGE SMITH -

Feature

FeatureWhen Dartmouth Had Its Own State (Almost)

May 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

FeatureThanks to Daniel Oliver, A Gathering of Lovers

May 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleThe Green: A House Mover and an ex-President Proved Who Owns It (Didn't They?)

May 1976 By Jabberwocky, Lewis Carroll, JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

May 1976 By WALTER C. DODGE, CHARLES J. ZIMMERMAN

M.B.R.

-

Article

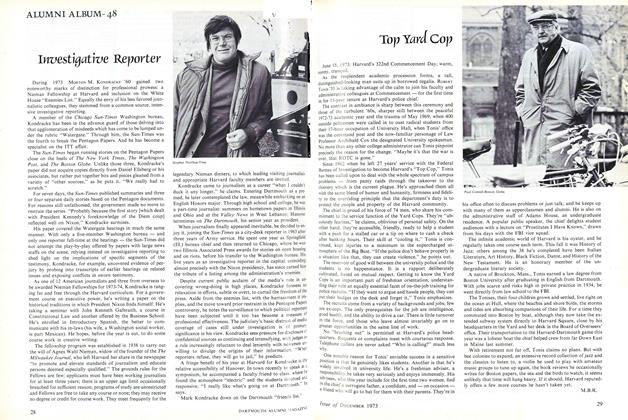

ArticleTop Yard Cop

December 1973 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleA Page for all Fords

May 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleGrown by Hand

October 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleMan in the Flying Machine

November 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleA Household Word Among the Voiceless

MAY 1978 By M.B.R. -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Fourteenth President

March 1981 By M.B.R.

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH CO-OP

June 1916 -

Article

ArticleMarch Glee Club Tour

MARCH 1969 -

Article

ArticlePotpourri

February 1977 -

Article

ArticleWomen volunteering lor community service ill Dartmouth outnumber men by a 2 to 1 ratio. How eome?

APRIL 1998 -

Article

ArticleWith the D.O.C.

March 1946 By Bill Wood '47N -

Article

ArticleRugby

December 1959 By CLIFF JORDAN '45