Among the numberless profound changes precipitated by 19th-century science and technology, few had as far-reaching effects as the revolution in the means of reproducing graphic images. At issue quite literally was how we saw ourselves. And at the end of the century We looked upon ourselves and our artifacts with different eyes than we had at the beginning Whereas in 1800 our images had been produced singly, laboriously by the traditional processes of engraving or aquatint, by 1900 we had produced, and could mass-reproduce, the modern photograph. Between the traditional and the modern, however, was the lithograph, the single graphic form which seems most characteristically to belong to the 19th century and to it alone.

The development of lithography, which provided an inexpensive way of mass-producing printed images, also coincided with the rise of the American city. In contemporary collections of 19th-century lithographs, therefore, there survives an invaluable visual record of the look and texture of American cities 100 to 140 years ago either shortly after their founding (in the West) or before 20th-century urban sprawl had obliterated the landmarks of earlier centuries (in the East).

A collection of lithographed views of our Western cities has become the subject of an absorbing piece of architectural, indeed social, history at the hands of John Reps. A professor in the College of Architecture at Cornell, he is not only a nationally recognized expert in contemporary city planning but also a noted historian of urban development in America. Cities on Stone, the most recent of several books by Reps on the urbanization of America, was designed to accompany a traveling exhibition of lithographs of city views mounted by the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art of Ft. Worth. Lavishly produced, the book contains not only Reps' history of lithography in general and city views in particular but also 50 full-color plates.

Once discovered, lithography quickly caught on and by 1830 was an established graphic medium in most major Eastern cities. An inexpensive and versatile means of satisfying our ancestors' cravings for pictures of all kinds was thus at hand, Reps explains, and they were ground out in profusion: "portraits, patriotic scenes, pioneer and Indian views, sporting prints ... depictions of natural disasters, military and naval engagements, Biblical scenes ... images of important buildings, theatre and tavern views and many other categories. Nothing failed to attract the interest of the public, escaped the eye of the artist, or lacked one or more lithographic publishers."

For reasons which Reps declines to speculate on - he is an architectural historian, not a sociologist - the lithograph immensely whetted the already keen craving of Americans to hang views of their cities on their parlor and office walls. He estimates that between 1825 and 1900 at least 2,000, and perhaps as many as 3,000. different urban views were published. So ubiquitous were they that another modern historian concludes that he would "hesitate to pick the most remote and unlikely place ... in the United States and say that there was no lithographed view of it."

With the California Gold Rush of 1849 the mania was transferred to Western cities and towns. Views of San Francisco in 1850. Monterey, the Sacramento waterfront in 1849; of Forest Hill, St. Louis, Union, Todds' Valley, Sonora Columbia, and Shasta, California, all mining towns, some destined to remain and grow, others to vanish with the gold claims which had spawned them: all were drawn by artists lithographed, and avidly collected back East. After the gold fever had abated, views of older, established Western towns were equally popular. The area between the Mississippi River and the Rockies also afforded its share of interesting, salable urban subjects. Albert Ruger, the most prolific lithographer of them all, was responsible for over 200 city views during his lifetime, including a famous view of Omaha and another of the Hannibal, Missouri, of the era of Mark Twain.

The artistic Establishment largely rejected or ignored this form of pop art, for it was undeniably tainted with odious commercialism, indeed advertising. To limit their financial risk, publishers of city views, or their drummers, customarily solicited pre-publication subscriptions. The price per print was between $3 and $10 depending on size, and occasionally artists were not above charging a local businessman for lettering in the name of his store prominently on a building or for including a picture of his establishment among the small border views that frequently surrounded the central print. Real estate firms and railroads were among the best customers, and city views were commonly used as framed wall hangings in professional and commercial offices where they served as highly visible icons of urban "progress."

By and large, historians agree, the city views are reasonably accurate, historically reliable representations. Occasionally local boosterism led to a certain gilding of the urban lily, as when a young Bostonian lured to Sumner, Kansas, by a widely displayed idyllic lithograph complained to his father back home of "lithographic fiction" and "engraved romance" because instead of the tidy, thriving city portrayed by the lithograph he had found only a "few log huts and miserable cabins." But, Reps concludes, "occasional artistic license in turning ahead the clock of history a year or two, darkening the sky with a bit more industrial smoke than local factories were producing, depicting the streets as if swept and watered, or the buildings as if freshly painted should not mislead us into thinking that these views present a completely romanticized version of Western cities." On the contrary, it is their accuracy, even to minute architectural details, which astonishes. "They truly convey the look of the urban West when the region was young and every town could dream of a golden future."

The Cities on Stone exhibition will be shown also at the Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, March 3-April 17; Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, May 5-June 19; Oakland Museum, Oakland, California, July 7-August 21; and Utah Museum of Fine Arts, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, September 18-October 30.

CITIES ON STONEBy John W. Reps '43Amon Carter Museum of Western Art1976, 99 pp., 50 color platesHardcover, $14.95; soft, $9.95

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAffirmative Action

April 1977 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureMr. Hopkins Builds a Library

April 1977 By CHARLES E. WIDMAyER -

Feature

FeatureIf you spent the winter in Buffalo, Imagine This

April 1977 By THOMAS SHERRY -

Feature

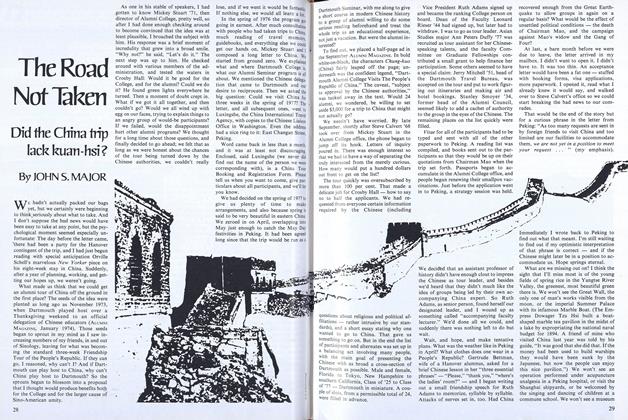

FeatureThe Road Not Taken

April 1977 By JOHN S. MAJOR -

Article

ArticleBetween Seasons

April 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleTopeka Takes On the Hun

April 1977 By NICK SANDOE '19

R.H.R.

-

Books

BooksNotes on a humanizing craft, a National Book Award, the Adamses, Avant-garde dancers, Irving Howe's tribute, and the Texas nation.

June 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on an expatriate's look homeward and on a bookman in a vast, sparsely inhabited region

October 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksMonticello to Montmartre

November 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on some gentlemen songsters, with an aside on "antique and toothless alumni"

December 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Pulitzer not given and on Dr. Bob, a gruff, humane Yankee who helped found AA

JUNE 1977 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksBound by Emotion

NOV. 1977 By R.H.R.

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

March 1919 -

Books

BooksJAPAN: IMAGES AND REALITIES.

JANUARY 1970 By ALMON B. IVES -

Books

BooksTHE KACHINA AND THE WHITE MAN.

October 1954 By EDWARD A. KENNARD '29 -

Books

BooksPETER HARRISON, FIRST AMERICAN ARCHITECT

July 1949 By Hugh Morrison '26 -

Books

BooksTHE BODY THAT WAS'T UNCLE

May 1939 By R. A. Burns -

Books

BooksELEMENTARY THEORY OP FINITE GROUPS.

February, 1931 By Robin Robinson

R.H.R.

-

Books

BooksNotes on a humanizing craft, a National Book Award, the Adamses, Avant-garde dancers, Irving Howe's tribute, and the Texas nation.

June 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on an expatriate's look homeward and on a bookman in a vast, sparsely inhabited region

October 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksMonticello to Montmartre

November 1976 By R.H.R.